Solution:

Differential diagnoses of tachycardia with a typical left bundle branch block (LBBB) QRS morphology include [

1]:

Supraventricular tachycardia with functional LBBB aberrancy

Antidromic right-sided reentrant tachycardia

Bundle branch reentrant ventricular tachycardia (BBRVT)

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) originating from the right ventricle

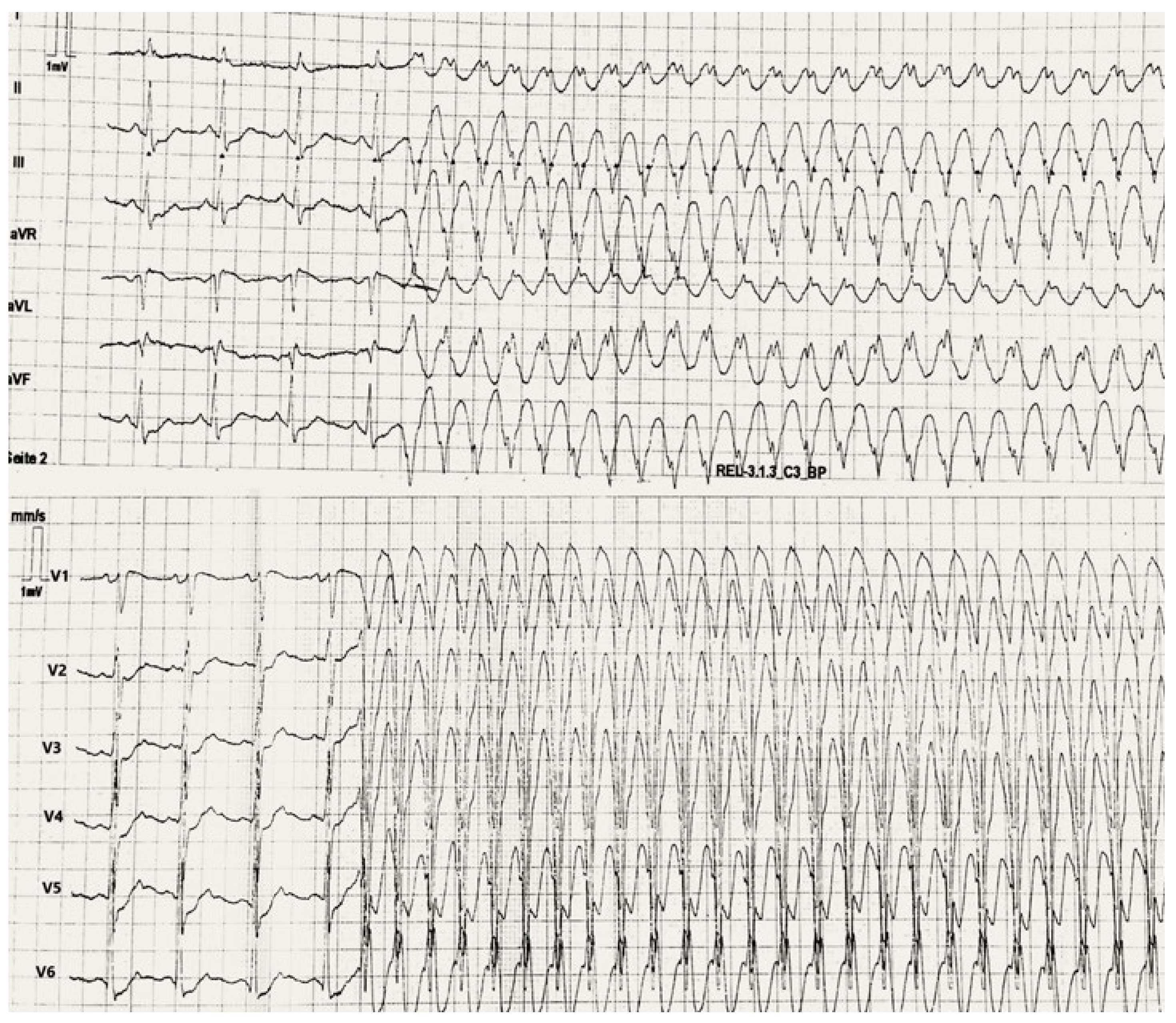

In a first step it is necessary to differentiate possible diagnoses using well-established multi-step algorithms. In

Figure 1, onset of tachy-cardia is documented. In sinus rhythm, apart from a shortened PR interval, a ST depression in chest leads is noticeable. When interpreting the 12-lead ECG during tachycardia, no atrio-ventricular dissociation is recognised as P waves nestled in the middle of T waves in lead V1. Other hallmark ECG features of VT, like chest lead positive or negative concordance, northwest QRS axis, right axis deviation in tachycardia with LBBB morphology, were absent. On the other hand, the tachycardia ECG shows different features that favour VT in the light of previously described Brugada, Vereckei aVR and limb leads algorithms (e.g., RS interval > 100 ms for QRS complexes in the precordial leads [V1–V6], initial dominant R wave in aVR). BBRVT is a kind of VT caused by macro-reentry within the bundle branches, mostly in patients with severe forms of dilated cardiomyopathy. ECGs taken during sinus rhythm typically show distal conduction system illness, such as a prolonged PR interval and a nonspecific “LBBB-like” intraventricular conduction delay. These characteristics make a BBRVT for our patient quite unlikely. At the same time, a structural normal heart renders a diagnosis of right-sided VT unlikely. Finally, an idiopathic VT that originates from the right ventricular outflow tract would have an inferior axis.

Supraventricular tachycardia with fixed or functional aberrancy is frequent in daily routine and sometimes an alternating tachycardia that switches between broad and narrow QRS complexes can be recorded. In this case, electrophysiologic study was decisive to exclude this potential diagnosis.

At this point, there are two separate recommendations for the acute management of WCT in the absence of an established diagnosis, considering haemodynamic stability [

2]. Synchronised DC cardioversion is a possible therapy and recommended in haemodynamically unstable patients or in case of failed drug therapy. If patients are haemodynamically stable, vagal manoeuvres (level of evidence [LOE] Class I C), intravenous (IV) adenosine administration (if no evidence of pre-excitation on resting ECG, LOE Class IIa C) and IV Class I antiarrhythmic drugs (LOE Class IIa B) are recommended consecutively. In this situation, IV amiodarone administration has limited level of evidence and in the event of an underlying accessory pathway with antegrade rapid conduction properties could cause acceleration or worsening of the tachycardia. This rule is also valid for the so-called “Mahaim fibres”, which are accessory pathways with node-like decremental properties [

3].

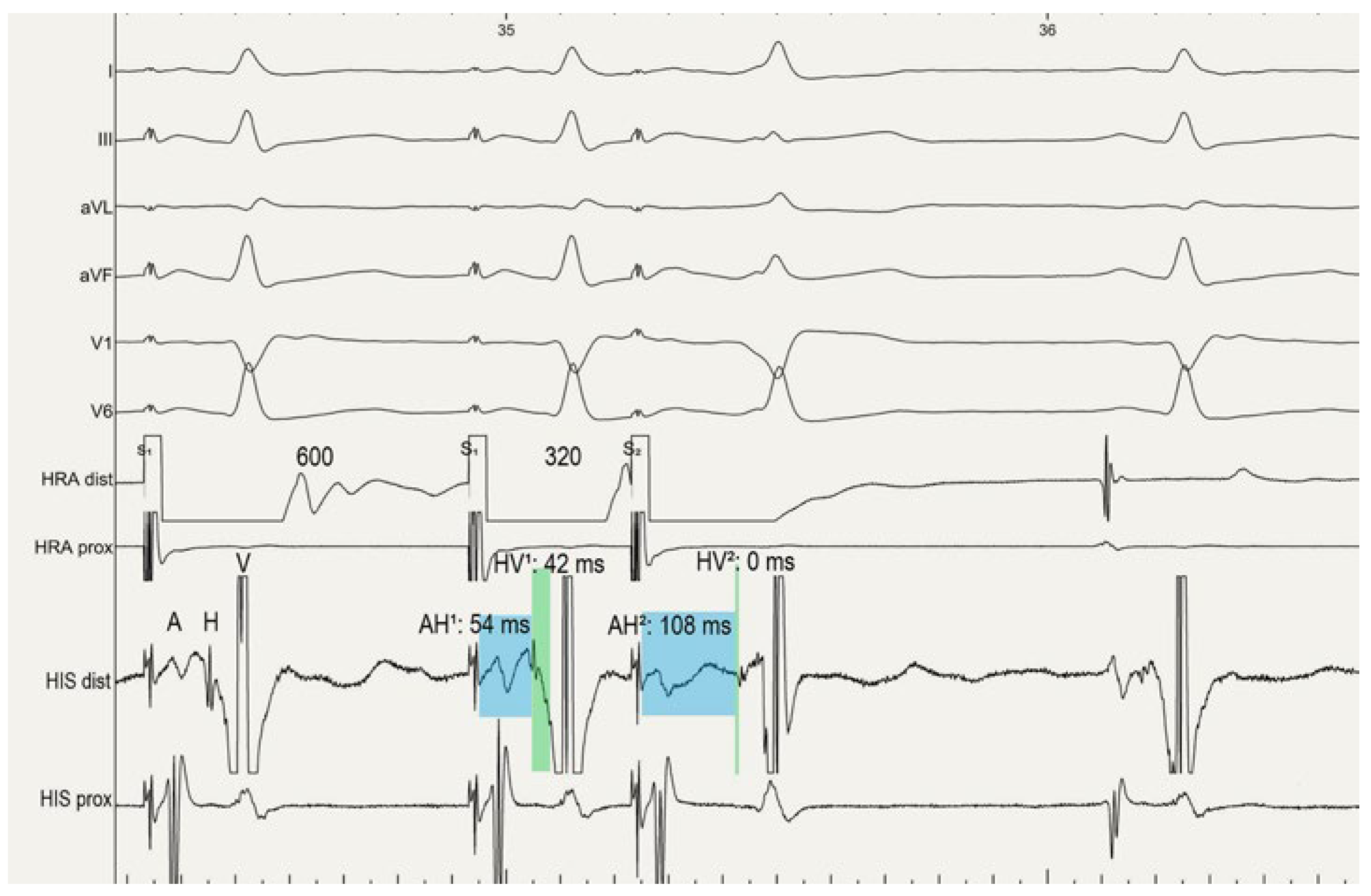

The patient underwent a subsequent electrophysiological study. After positioning a diagnostic decapolar catheter in the coronary sinus (CS) and a diagnostic quadripolar catheter each at the His bundle, in the right ventricular (RV) apex and in the lateral high right atrium (HRA), basic measurements were within the normal range (HV time 42 ms in sinus rhythm). The CS activation sequence under RV stimulation was concentric and showed decremental properties. No progressive fusion occurred in the surface ECG with incremental atrial pacing from distal and proximal poles of the CS catheter. However, we unmasked a pre-excitation pattern when incremental atrial pacing was started from the lateral right atrium. During programmed right atrial stimulation, a prolongation of the atrial electrogram, His (AH interval) time, simultaneous shortening of the HV time to 0 ms (even negative HV interval) and an increase in pre-excitation was demonstrated (

Figure 2). Fully pre-excited QRS morphology in the surface ECG was identical with WCT during right atrial pacing. Next, antegrade activation mapping under right atrial stimulation proved that the earliest ventricular activation was on the lateral tricuspid anulus (−32 ms before onset of QRS), but no Mahaim potential was detectable at this point. As no tachycardia was inducible, we assumed that clinical tachycardia was most likely an antidromic Mahaim atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia. Therefore, a successful ablation of the ventricular insertion at the lateral tricuspid anulus (LAO 45°, 8 o’clock) was performed and the accessory pathway conduction was abolished. Since then, the patient is free of any arrhythmias at 3 months follow-up.

Figure 2.

Programmed atrial stimulation from the HRA revealed the pre-excitation. During programmed atrial stimulation, prolongation of the AH interval (AH1: 54 ms < AH2: 108 ms) and shortening of HV2 interval (HV: 0 ms) demonstrated a decremental right sided accessory pathway. HRA = high right atrium, CS = coronary sinus, HIS = His bundle recordings, AH interval = Atrial electrogram to His electrogram, HV = His electrogram to the earliest onset of ventricular activation.

Figure 2.

Programmed atrial stimulation from the HRA revealed the pre-excitation. During programmed atrial stimulation, prolongation of the AH interval (AH1: 54 ms < AH2: 108 ms) and shortening of HV2 interval (HV: 0 ms) demonstrated a decremental right sided accessory pathway. HRA = high right atrium, CS = coronary sinus, HIS = His bundle recordings, AH interval = Atrial electrogram to His electrogram, HV = His electrogram to the earliest onset of ventricular activation.