Abstract

Cardiovascular disease is the primary cause of mortality in the world, and tightly associated with the metabolic syndrome, which is a cluster of interconnected metabolic dysfunctions including insulin resistance, obesity, hypertension and dyslipidaemias. These dysfunctions increase the risk of developing atherosclerosis and consequent cardiovascular diseases, such as myocardial infarction and stroke. Atherosclerosis is primarily triggered by increased plasma cholesterol levels and can be classified as an immunometabolic disease, a chronic disease that is affected by both metabolic and inflammatory triggers and/or mediators. These triggers and mediators activate common downstream pathways, including nuclear receptor signalling. Interestingly, specific cofactors that bind to these complexes act as immunometabolic integrators. This review provides examples of such co-regulator complexes, including nuclear sirtuins, nuclear receptor co-repressor 1 (NCOR1), nuclear receptor interacting protein 1 (NRIP1), and prospero homeobox 1 (PROX1). Their study might provide novel insight into mechanistic regulations and the identification of new targets to treat atherosclerosis.

Increased plasma cholesterol triggers atherogenesis

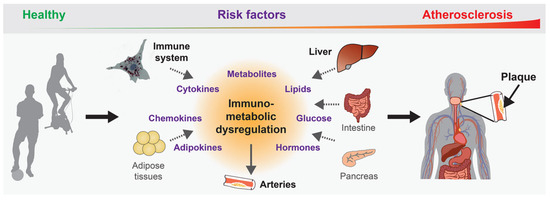

Atherosclerosis is a chronic immunometabolic disease and remains asymptomatic until a plaque becomes large enough to obstruct the lumen to cause ischaemic pain or ruptures causing a myocardial infarction, stroke or peripheral artery disease. Research over the past decades demonstrated that the chronic accumulation of lipids, especially cholesterol, in our circulation is the major trigger of atherosclerosis. First, most gene candidates identified in familial genetic or genome-wide association studies for coronary artery disease or atherosclerosis, are associated with lipid and/or lipoprotein metabolism [1,2]. Second, the primary choice of treatment in patients with high-risk to develop cardiovascular diseases is to lower the levels of circulating total and low density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol by primarily targeting hepatic cholesterol metabolism and/or the intestinal cholesterol uptake, with, for example, statins, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors and/or ezetimibe [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Third, all the genetic and dietary mouse models that are used to promote atherosclerosis development function by primarily altering the lipoprotein metabolism towards a humanised profile [11]. This knowledge suggests that the hyperlipidaemia, especially the hypercholesterolaemia, combined with the genetic predisposition is the major trigger of the disease. Nevertheless, recent research showed that metabolic and inflammatory processes are closely interconnected at the cellular level as well as via intra- and inter-organ communication (Figure 1) [12,13].

Figure 1.

Immunometabolic dysregulation promotes atherogenesis. Different organs contribute to atherogenesis by expressing and/or secreting immunometabolic mediators upon exposure to atherogenic risk factors over our lifetime, which leads to the chronic dysregulation that promotes the disease development and progression.

The liver regulates systemic cholesterol metabolism

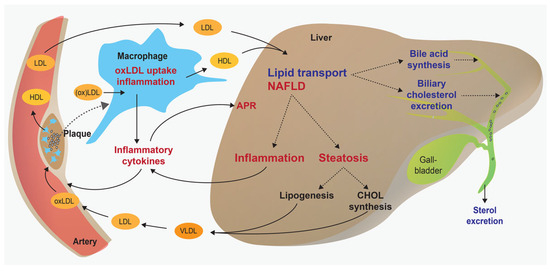

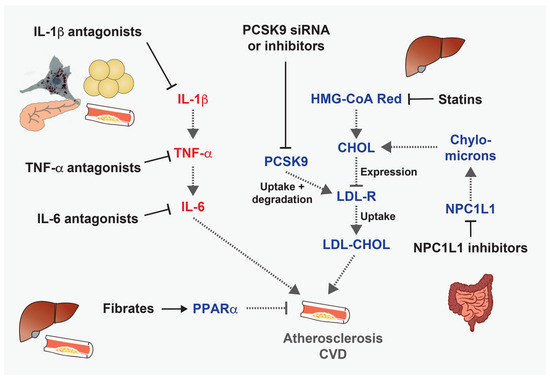

The liver plays a crucial role in the development of atherosclerosis by regulating metabolic and inflammatory processes, such as the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and acute phase response proteins, the secretion of very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles, the uptake of cholesterol from the circulation, and biliary cholesterol excretion (Figure 2). An immunometabolic dysregulation in the liver can promote nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and the development of atherosclerosis. Importantly, NAFLD leads to adverse cardiovascular functions, such as increased oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, hypercoagulability and accelerated development of atherosclerosis [14,15,16]. Most of the currently used drugs primarily target hepatic cholesterol synthesis via the inhibition of hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMGCA) reductase (statins) or hepatic cholesterol re-uptake from the circulation by decreasing the breakdown of the LDL receptor (e.g., PCSK9 inhibitors or silencing) [4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

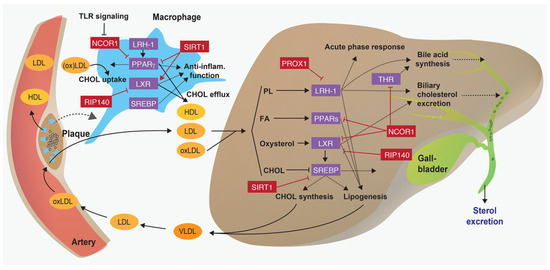

Figure 2.

Contribution of the liver and macrophages to atherogenesis. Overview displaying protective and deleterious functions of the liver and macrophages in atherogenesis. For example, the liver promotes the beneficial biliary excretion of cholesterol, but on the other hand it can promote increased VLDL secretion and inflammatory cytokine expression. Chronic inflammation and lipid accumulation in the liver can further increase the risk of atherosclerosis. APR = acute phase response; NAFLD = nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; oxLDL = oxidised low-density lipoprotein; VLDL = very low-density lipoprotein.

Macrophage foam cells promote plaque development

Upon exposure to atherogenic triggers, vascular endothelial cells are activated and start to express adhesion molecules. These adhesion molecules attract and activate blood monocytes, which then transmigrate into the arterial intima. Macrophages are the most abundant population of cells within the plaques and one hallmark of atherogenesis is the excessive accumulation of cholesterol in monocytederived macrophages, leading to foam cell formation. The uptake of modified – especially oxidised – low-density lipoproteins (oxLDL) is driven by scavenger receptors and these are stored as cholesterol esters in lipid droplets. Moreover, macrophages interact with other immune cells, especially T cells, and this immune response can promote pro- or anti-inflammatory processes (Figure 2) [17,18].

Clinical evidence of immunometabolic regulation

Several powerful cardiovascular drugs demonstrated that metabolic and inflammatory processes can be targeted to treat atherosclerosis (Figure 3), such as the HMG-CA reductase inhibitors (statins) to lower LDL-cholesterol levels, or interleukin-1β (IL-1β) receptor antagonists or colchicine to block the pro-inflammatory processes in cardiovascular disease and type-2 diabetes [4,5,19,20,21]. Although these drugs primarily target either a metabolic or an inflammatory process, recent research demonstrated that they do also affect inflammatory or metabolic signalling, respectively. For example, besides targeting the HMG-CA reductase, statins exert various pleiotropic effects that are mediated by intermediates of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway. A recent study demonstrated that, by inhibiting mevalonate synthesis, statins counteract the epigenetic reprogramming that leads to trained immunity in monocytederived macrophages [22]. Other metabolites of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway, such as farnesyl pyrophosphate and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, also exhibit important anti-inflammatory effects [23]. Further studies demonstrated that statins also modulate the response of the adaptive immune system, such as the function of Th17 cells in autoimmune disease [24].

Figure 3.

Anti-atherosclerotic and/or cardioprotective drugs targeting inflammatory or metabolic pathways. Examples of drugs that target inflammatory or metabolic processes that promote the development of atherosclerosis.

Crosstalk of inflammatory and metabolic signalling

One of the first hints for a direct role of inflammatory processes in the development of a metabolic disease came in the 1990s, when it was shown that normal and atherosclerotic arteries express tumour necrosis factor (TNF) [25]. Two years later, it was demonstrated that the adipose tissue secretes TNF in obese and/or diabetic mice and humans, thereby directly linking an inflammatory cytokine to another chronic metabolic disease [26,27,28]. Later studies showed that the genetic deletion of Tnf reduces atherosclerosis development [29,30,31], and it is now known that various cytokines and chemokines regulate atherogenesis [32,33].

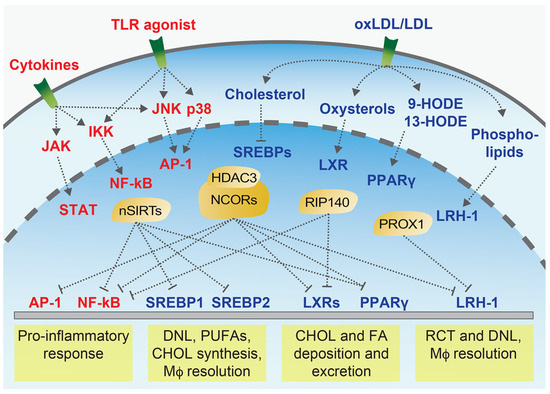

Binding of TNF and other cytokines and chemokines to their corresponding receptors induces the activation of downstream signalling kinases, including IκB kinase (IKK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), p38 and Janus kinase (JAK) (Figure 4). Signalling from these kinases leads to the activation of central inflammatory transcription factors, such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) upon IKK signalling, activating protein-1 (AP-1) upon p38/JNK (MAPK) signalling, or signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) upon JAK1 signalling. Notably, these inflammatory transcription factors also regulate metabolic processes at different layers. For example, they interact with and coordinate the transcriptional activity of metabolic transcription factors, such as the nuclear receptors peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and liver X receptors (LXRs), which in turn are activated by specific lipids [34,35,36]. Furthermore, inflammatory signalling can induce the expression of central metabolic regulators, such as sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBP-1 and SREBP-2), and of a series of metabolic enzymes [37,38,39,40,41].

Figure 4.

Immunometabolic signalling at the cellular level. Simplified overview of important signalling pathways that are activated by inflammatory or metabolic mediators, such as cytokines and lipids, which trigger downstream inflammatory (red labels) or metabolic pathways (blue labels), and activate key transcription factors. Transcription cofactors (yellow) play a central immunometabolic role by directly reacting to upstream immune and metabolic mediators and coordinating the downstream responses at the nuclear level, either by directly driving the expression of target genes or by interfering with the function (e.g., transrepression) of other transcription factors, such as the AP-1 or NF-κB. CHOL = cholesterol; FA = fatty acid; HODE = Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid; DNL = de novo lipogenesis; Mϕ = macrophage; nSIRTs = nuclear Sirtuins; PUFAs = polyunsaturated fatty acids; RCT = reverse cholesterol transport.

Lipid-responsive nuclear receptors with immunometabolic functions

The family of nuclear receptors can be subdivided into endocrine receptors that are bound by hormones, adopted orphan nuclear receptors that are activated by different metabolites such as fatty acids and cholesterol derivates, and orphan nuclear receptors that do not (yet) have any known natural ligand [42,43]. Importantly, most nuclear receptors have a ligand binding pocket and are therefore potential drug targets. The function of several nuclear receptors in atherosclerosis has been reviewed previously [44]. The class of adopted and orphan nuclear receptors is of special interest since several of them are bound and activated by specific lipids, such as PPARγ, LXRs and liver receptor homologue-1 (LRH-1) (Figure 4). Besides regulating various metabolic processes, these lipid-binding nuclear receptors also mediate transrepression of pro-inflammatory molecules in metabolic organs and immune cells [34,35,36,45,46,47], thus acting as immunometabolic regulators.

Transcription cofactors as immunometabolic integrators

Transcriptional co-regulators play a central role in immunometabolic regulation because they are regulated by upstream inflammatory or metabolic mediators and coordinate the transcriptional activity of key immunometabolic transcription factors. Importantly, several cofactors are expressed in a tissue-specific manner, at a specific time point during development or upon specific upstream stimuli, therefore acting under very specific conditions. From an immunometabolic point of view it will be very interesting to identify and study the co-regulators that are implicated in both inflammatory and metabolic processes. Approximately 300 transcriptional cofactors exist in mammalian cells [48], but the function of most these cofactors is not yet known. The functions of some selected cofactors that regulate atherogenesis are summarised below.

Sirtuins – multiple roles in atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases

Sirtuins are nutrient-sensitive protein deacetylases, which play important roles in various molecular and physiological processes [49]. SIRT1, the best studied sirtuin, exerts various protective cardiovascular functions. Several studies demonstrated that SIRT1 diminishes the development of atherosclerosis and exhibits other cardioprotective effects (Figure 5) [51,52]. By deacetylating and interfering with the activation of the RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB, SIRT1 inhibits inflammatory signalling, prevents macrophage foam cell formation, diminishes endothelial cell activation and reduces the expression of tissue factor, a key factor in the activation of the coagulation cascade during arteriothrombosis [53,54,55,56]. Besides exerting these direct anti-inflammatory effects, SIRT1 also regulates the function of specific nuclear receptors. These studies highlight that SIRT1 acts as an immunometabolic regulator. Other sirtuins also exert distinct cardioprotective functions (reviewed in [57]). Several approaches that were tested in order to induce the activity of sirtuins by increasing the levels of its substrate, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), showed protective cardiometabolic effects [58,59,60,61,62,63].

Figure 5.

Regulation of immunometabolic processes by nuclear receptor-corepressor networks. Scheme illustrating how transcriptional corepressor complexes (in red) repress the function of nuclear receptors and SREBPs (in purple) and thus regulate key atherosclerotic processes in the liver and macrophages. CHOL = cholesterol; FA = fatty acid; oxLDL = oxidised LDL; PL = phospholipid; THR = thyroid hormone receptor. Adapted from [50].

NCOR1 – an emerging regulator of immunometabolic processes

NCOR1 forms a large co-repressor complex containing histone deacetylases that inhibit the transcriptional function of nuclear receptors [64,65]. Tissue-specific deletions of Ncor1 in metabolic organs showed that it regulates fatty acid metabolism, mitochondrial functions, insulin sensitivity, bile acid composition and intestinal cholesterol absorption [66,67,68,69]. Moreover, NCOR1 exerts both proand antiinflammatory functions in macrophages, and its deletion in adipocytes reduces adipose tissue macrophage infiltration and inflammation [35,67,70,71].

Recently published data demonstrated that the deletion of macrophage Ncor1 promotes atherosclerosis development in mice, and their atherosclerotic lesions displayed thinner fibrous caps and larger necrotic cores, suggesting that NCOR1 stabilises atherosclerotic plaques [72]. At the molecular level, it was shown that NCOR1 binds to the Cd36 promoter, a scavenger receptor that mediates the uncontrolled uptake of modified LDL particles [73,74]. Consequently, NCOR1-deficient peritoneal macrophages displayed increased CD36 expression and enhanced accumulation of oxLDL compared with control macrophages (Figure 5). The increased expression of CD36 was secondary to a derepression of PPARγ target genes. Treatment of peritoneal macrophages with the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone led to an enhanced expression of several direct and indirect PPARγ target genes, including both proand anti-inflammatory molecules, thus suggesting that NCOR1 exerts atheroprotective functions by repressing detrimental functions of PPARγ in macrophages (Figure 5).

To establish the contribution of macrophage NCOR1 in human atherosclerosis, the authors further explored its expression in publicly available datasets and showed that the expression of Ncor1 was reduced in carotid plaques in comparison to non-atherosclerotic biopsies from mammary arteries. Moreover, analysis of expression data from laser micro-dissected macrophages [75] revealed that all significantly changed PPARγ target genes were robustly increased in macrophages from ruptured compared with non-ruptured plaques, and targeted protein analyses showed that NCOR1 is reduced in ruptured compared to non-ruptured carotid plaque [72].

Earlier studies demonstrated that NCOR1 can also interact with B cell lymphoma-6 (BCL6), a transcriptional repressor that belongs to a class of zinc-finger transcription factors. This interaction promotes the repression of several processes, including the expression of pro-inflammatory NF-κB target genes [76,77,78].

In the liver, nuclear co-repressors modulate liver energy metabolism during the fasting-feeding transition. The NCOR1-HDAC3 complex regulates both catabolic and anabolic processes in the liver. Upon feeding, the target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)-AKT signalling pathway is activated by increasing levels of glucose and insulin, which leads to the phosphorylation of serine 1460 of NCOR1 (pS1460 NCOR1). The pS1460 phosphorylation reduces the capacity of NCOR1 to interact with LXRs, hence increasing the transcription of de novo lipogenesis genes, and conversely, it fosters the interaction with PPARα and ERRα, thus subsequently repressing downstream ketogenic and Oxphos genes [68]. Under fasting conditions, the NCOR1-HDAC3 complex represses the expression of de novo lipogenesis genes (Figure 5) [79,80].

PROX1 – a critical regulator of hepatic metabolism

Prospero-related homeobox 1 (PROX1) is a conserved corepressor that is mainly expressed in liver, lymphatic vessels, lens, dentate gyrus, neuroendocrine cells of the adrenal medulla, megakaryocytes, and platelets [81]. It interacts with several nuclear receptors, including the LRH-1, oestrogen-related receptor (ERR), steroid and xenobiotic receptor (SXR), and retinoic acid-related orphan receptors (ROR), as well as other transcriptional regulators, such as HDAC3 or lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) [82,83,84]. The interaction of PROX1 with LRH-1 was first described in Drosophila [85] and human cells [86], and the LRH-1/PROX1 interaction has been reported to regulate liver development and function [86,87]. Importantly, it was demonstrated that PROX1 is required to promote the beneficial effects of LRH-1 on reverse cholesterol transport and atherogenesis: Atherosclerosis-prone mice carrying a mutation that abolishes the SUMOylation of LRH-1 are significantly protected from atherosclerosis development by promoting reverse cholesterol transport (Figure 5) [88]. This study highlighted that a single posttranslational modification of a nuclear receptor is sufficient to modulate the function of the protein and impact on the development of chronic cardiovascular diseases. Moreover, LRH-1 drives the differentiation of macrophages towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype (Figure 5) [89] . Whether or not the LRH-1-PROX1 complex affects the development of atherosclerosis in humans in not yet known. However, as it is a potent regulator of bile acid synthesis and composition [90], it is tempting to assume that this nuclear receptor-co-repressor complex plays a key role in chronic hepatic diseases or upon liver transplantation. On the other hand, the same LRH-1 mutation promotes the development of NAFLD and early signs of steatohepatitis and Lrh-1-deficient mice are protected against hepatic cancer [91,92].

RIP140 – a regulator of macrophage metabolism and inflammation

Nuclear receptor interacting protein 1 (NRIP1; also known as receptor interacting protein 140, RIP140) is a co-regulator that is ubiquitously expressed, interacts with several nuclear receptors and regulates downstream immunometabolic processes [93,94]. Interestingly, TLR signalling leads to RIP140 ubiquitination and degradation, which in turn reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine production and promotes endotoxin tolerance [95]. Moreover, RIP140 promotes foam cell formation by inhibiting LXR-driven Abca1 and Abag1 expression, thus impairing HDL-driven cholesterol efflux from macrophages [96,97]. Consistently, microRNA-specific silencing of Rip140 in macrophages reduces the development of atherosclerotic lesions in Apoe knockout mice (Figure 5) [96].

In the liver, RIP140 is recruited to a complex of krüppellike factor 15 (KLF15) and LXR/RXR on the promoter of genes regulating de novo lipogenesis and thus regulating the feeding-fasting transition (Figure 5) [98,99]. This RIP140-KLF15-LXR complex likely regulates other processes that affect atherosclerosis development in the liver, macrophages and other tissues. Notably, KLF15 mRNA expression is reduced in human atherosclerotic compared to nonatherosclerotic aortae, and the systemic or smooth muscle cell-specific deletion of Klf15 aggravates atherosclerosis development in Apoe knockout mice [100].

Outlook

Myocardial infarction and stroke are the leading causes of mortality worldwide, and atherosclerotic plaque rupture or erosion are the primary triggers of these two cardiovascular diseases. Currently, the primary approach to reduce the progression of atherosclerosis in humans is to target the dyslipidaemia, especially by reducing increased LDL-cholesterol levels, besides treating hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Targeting the LDL metabolism levels will continue to be primary intervention in patients with increased total and LDL-cholesterol, which can now be successfully achieved by combining statins with intestinal Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1 (NPC1L1) or hepatic PCSK9 inhibitors [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Furthermore, new drugs to treat dyslipidaemias are emerging, such as apolipoprotein C3 (ApoC3), Apo(a) or angiopoietin like 3 (ANGPTL3) silencing therapeutics [101].

Another potent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events besides LDL-cholesterol is high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), thus suggesting that targeting central pro-inflammatory processes will likely also be a future therapeutic option. This is also underlined by the success of the recent COLCOT and CANTOS trials [19,21]. Therefore, there is a clear biomedical interest in identifying, understanding and testing new (anti-)atherogenic pathways as therapeutic targets.

Targeting specific nuclear receptor-cofactor complexes could become a promising approach to promote beneficial metabolic functions and inhibit chronic anti-inflammatory processes. Some examples were discussed in this review, but research over past years identified many more promising targets for cardiovascular diseases [102]. For instance, strategies to stabilise or augment NCOR1 function in macrophages could protect against excessive oxLDL uptake, macrophage foam cell formation and pro-inflammatory gene expression, and thus prevent further growth and destabilisation of atherosclerotic plaques [50,72], such as in primary prevention for patients with very high risk for atherosclerotic disease or in secondary prevention. In the liver, targeting NCOR1, for example with synthetic siRNAs conjugated to triantennary N-acetylgalactosamine carbohydrates [9,103], could be tested to prevent fatty acid and cholesterol synthesis in patients with NAFLD, which is a growing patient population globally and exposed to increased cardiovascular risk [50,68]. However, these therapeutic approaches first have to be tested in pre-clinical models before being translated to humans.

Funding

SS was financially supported by the Swiss Heart Foundation (FF19025).

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- Kessler, T.; Vilne, B.; Schunkert, H. The impact of genome-wide association studies on the pathophysiology and therapy of cardiovascular disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2016, 8, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R. Genetics of coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2014, 114, 1890–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, C.P.; Blazing, M.A.; Giugliano, R.P.; McCagg, A.; White, J.A.; Theroux, P.; et al.; IMPROVE-IT Investigators Ezetimibe Added to Statin Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015, 372, 2387–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.E.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Schoenhagen, P.; Crowe, T.; Sasiela, W.J.; Tsai, J.; et al.; Reversal of Atherosclerosis with Aggressive Lipid Lowering (REVERSAL) Investigators Statin therapy, LDL cholesterol, C-reactive protein, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005, 352, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Cannon, C.P.; Morrow, D.; Rifai, N.; Rose, L.M.; McCabe, C.H.; et al.; Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection TherapyThrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 (PROVE IT-TIMI 22) Investigators C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005, 352, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Giugliano, R.P.; Keech, A.C.; Honarpour, N.; Wiviott, S.D.; Murphy, S.A.; et al.; FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Steg, P.G.; Szarek, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Bittner, V.A.; Diaz, R.; et al.; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018, 379, 2097–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raal, F.J.; Kallend, D.; Ray, K.K.; Turner, T.; Koenig, W.; Wright, R.S.; et al.; ORION-9 Investigators Inclisiran for the Treatment of Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, K.K.; Landmesser, U.; Leiter, L.A.; Kallend, D.; Dufour, R.; Karakas, M.; et al. Inclisiran in Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk with Elevated LDL Cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 1430–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, K.K.; Wright, R.S.; Kallend, D.; Koenig, W.; Leiter, L.A.; Raal, F.J.; et al.; ORION-10 and ORION-11 Investigators Two Phase 3 Trials of Inclisiran in Patients with Elevated LDL Cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 1507–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppi, S.; Lüscher, T.F.; Stein, S. Mouse Models for Atherosclerosis Research-Which Is My Line? Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G.S. Foundations of Immunometabolism and Implications for Metabolic Health and Disease. Immunity. 2017, 47, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltiel, A.R.; Olefsky, J.M. Inflammatory mechanisms linking obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Invest. 2017, 127, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anstee, Q.M.; Targher, G.; Day, C.P. Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013, 10, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, L.S.; Curzen, N.P.; Calder, P.C.; Byrne, C.D. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a new and important cardiovascular risk factor? Eur Heart J. 2012, 33, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J Hepatol. 2015, 62 (Suppl. 1), S47–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, T.; Prange, K.H.M.; Glass, C.K.; de Winther, M.P.J. Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of macrophages in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020, 17, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabas, I.; Lichtman, A.H. Monocyte-Macrophages and T Cells in Atherosclerosis. Immunity. 2017, 47, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Thuren, T.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Chang, W.H.; Ballantyne, C.; et al.; CANTOS Trial Group Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017, 377, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, C.M.; Faulenbach, M.; Vaag, A.; Vølund, A.; Ehses, J.A.; Seifert, B.; et al. Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356, 1517–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tardif, J.C.; Kouz, S.; Waters, D.D.; Bertrand, O.F.; Diaz, R.; Maggioni, A.P.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Low-Dose Colchicine after Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019, 381, 2497–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkering, S.; Arts, R.J.W.; Novakovic, B.; Kourtzelis, I.; van der Heijden, C.D.C.C.; Li, Y.; et al. Metabolic Induction of Trained Immunity through the Mevalonate Pathway. Cell. 2018, 172, 135–146.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiser, R. Immune modulatory effects of statins. Immunology. 2018, 154, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulivieri, C.; Baldari, C.T. Statins: from cholesterol-lowering drugs to novel immunomodulators for the treatment of Th17-mediated autoimmune diseases. Pharmacol Res. 2014, 88, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, H.G.; Niculescu, F.; Vlaicu, R. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human arterial wall with atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1991, 89, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotamisligil, G.S.; Shargill, N.S.; Spiegelman, B.M. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993, 259, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G.S.; Arner, P.; Caro, J.F.; Atkinson, R.L.; Spiegelman, B.M. Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1995, 95, 2409–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, P.A.; Saghizadeh, M.; Ong, J.M.; Bosch, R.J.; Deem, R.; Simsolo, R.B. The expression of tumor necrosis factor in human adipose tissue. Regulation by obesity, weight loss, and relationship to lipoprotein lipase. J Clin Invest. 1995, 95, 2111–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brånén, L.; Hovgaard, L.; Nitulescu, M.; Bengtsson, E.; Nilsson, J.; Jovinge, S. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004, 24, 2137–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, H.; Wada, H.; Niwa, T.; Kirii, H.; Iwamoto, N.; Fujii, H.; et al. Disruption of tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene diminishes the development of atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2005, 180, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canault, M.; Peiretti, F.; Mueller, C.; Kopp, F.; Morange, P.; Rihs, S.; et al. Exclusive expression of transmembrane TNF-alpha in mice reduces the inflammatory response in early lipid lesions of aortic sinus. Atherosclerosis. 2004, 172, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Noels, H. Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med. 2011, 17, 1410–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusters, P.J.; Lutgens, E. Cytokines and Immune Responses in Murine Atherosclerosis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015, 1339, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, G.; Fong, A.L.; Ogawa, S.; Gamliel, A.; Li, A.C.; Perissi, V.; et al. A SUMOylation-dependent pathway mediates transrepression of inflammatory response genes by PPAR-gamma. Nature. 2005, 437, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisletti, S.; Huang, W.; Jepsen, K.; Benner, C.; Hardiman, G.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; et al. Cooperative NCoR/SMRT interactions establish a corepressor-based strategy for integration of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signaling pathways. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venteclef, N.; Jakobsson, T.; Steffensen, K.R.; Treuter, E. Metabolic nuclear receptor signaling and the inflammatory acute phase response. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011, 22, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatore, L.; Thotakura, A.K.; Bennett, J.; Moretti, M.; Franzoso, G. The nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathway: integrating metabolism with inflammation. Trends Cell Biol. 2012, 22, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodington, D.W.; Desai, H.R.; Woo, M. JAK/STAT Emerging Players in Metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018, 29, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, M.; Masaki, T.; Seike, M.; Yoshimatsu, H. TNF-alpha induces hepatic steatosis in mice by enhancing gene expression of sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c). Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007, 232, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hasenfuss, S.C.; Bakiri, L.; Thomsen, M.K.; Williams, E.G.; Auwerx, J.; Wagner, E.F. Regulation of steatohepatitis and PPARγ signaling by distinct AP-1 dimers. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manieri, E.; Sabio, G. Stress kinases in the modulation of metabolism and energy balance. J Mol Endocrinol. 2015, 55, R11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, C.K.; Ogawa, S. Combinatorial roles of nuclear receptors in inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006, 6, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.A.; Fayard, E.; Picard, F.; Auwerx, J. Nuclear receptors and the control of metabolism. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003, 65, 261–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurakula, K.; Hamers, A.A.; de Waard, V.; de Vries, C.J. Nuclear Receptors in atherosclerosis: a superfamily with many ‘Goodfellas’. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013, 368, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghisletti, S.; Huang, W.; Ogawa, S.; Pascual, G.; Lin, M.E.; Willson, T.M.; et al. Parallel SUMOylation-dependent pathways mediate geneand signalspecific transrepression by LXRs and PPARgamma. Mol Cell. 2007, 25, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, C.K.; Saijo, K. Nuclear receptor transrepression pathways that regulate inflammation in macrophages and T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010, 10, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treuter, E.; Venteclef, N. Transcriptional control of metabolic and inflammatory pathways by nuclear receptor SUMOylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011, 1812, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.M.; Chen, H.; Liu, W.; Liu, H.; Gong, J.; Wang, H.; et al. AnimalTFDB: a comprehensive animal transcription factor database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D144–D149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Auwerx, J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, M.A.; Guillaumon, A.T.; Paneni, F.; Matter, C.M.; Stein, S. Role of the Nuclear Receptor Corepressor 1 (NCOR1) in Atherosclerosis and Associated Immunometabolic Diseases. Front Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnik, S.; Stein, S.; Matter, C.M. SIRT1 an anti-inflammatory pathway at the crossroads between metabolic disease and atherosclerosis. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2012, 10, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.; Matter, C.M. Protective roles of SIRT1 in atherosclerosis. Cell Cycle. 2011, 10, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenstein, A.; Stein, S.; Holy, E.W.; Camici, G.G.; Lohmann, C.; Akhmedov, A.; et al. Sirt1 inhibition promotes in vivo arterial thrombosis and tissue factor expression in stimulated cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2011, 89, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.; Lohmann, C.; Schäfer, N.; Hofmann, J.; Rohrer, L.; Besler, C.; et al. SIRT1 decreases Lox-1-mediated foam cell formation in atherogenesis. Eur Heart J. 2010, 31, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.; Schäfer, N.; Breitenstein, A.; Besler, C.; Winnik, S.; Lohmann, C.; et al. SIRT1 reduces endothelial activation without affecting vascular function in ApoE-/mice. Aging (Albany NY). 2010, 2, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schug, T.T.; Xu, Q.; Gao, H.; Peres-da-Silva, A.; Draper, D.W.; Fessler, M.B.; et al. Myeloid deletion of SIRT1 induces inflammatory signaling in response to environmental stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2010, 30, 4712–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winnik, S.; Auwerx, J.; Sinclair, D.A.; Matter, C.M. Protective effects of sirtuins in cardiovascular diseases: from bench to bedside. Eur Heart J. 2015, 36, 3404–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsyuba, E.; Auwerx, J. Modulating NAD+ metabolism, from bench to bedside. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 2670–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsyuba, E.; Mottis, A.; Zietak, M.; De Franco, F.; van der Velpen, V.; Gariani, K.; et al. De novo NAD+ synthesis enhances mitochondrial function and improves health. Nature. 2018, 563, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.J.; Bernier, M.; Aon, M.A.; Cortassa, S.; Kim, E.Y.; Fang, E.F.; et al. Nicotinamide Improves Aspects of Healthspan, but Not Lifespan, in Mice. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 667–676.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.F.; Yoshida, S.; Stein, L.R.; Grozio, A.; Kubota, S.; Sasaki, Y.; et al. Long-Term Administration of Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Mitigates Age-Associated Physiological Decline in Mice. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajman, L.; Chwalek, K.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic Potential of NADBoosting Molecules: The In Vivo Evidence. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.E.; Choi, J.Y.; Stein, S.; Ryu, D. Implications of NAD+ boosters in translational medicine. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottis, A.; Mouchiroud, L.; Auwerx, J. Emerging roles of the corepressors NCoR1 and SMRT in homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 819–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perissi, V.; Jepsen, K.; Glass, C.K.; Rosenfeld, M.G. Deconstructing repression: evolving models of co-repressor action. Nat Rev Genet. 2010, 11, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Williams, E.G.; Mouchiroud, L.; Cantó,,, C. ; Fan, W.; Downes, M.; et al. NCoR1 is a conserved physiological modulator of muscle mass and oxidative function. Cell. 2011, 147, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Fan, W.; Xu, J.; Lu, M.; Yamamoto, H.; Auwerx, J.; et al. Adipocyte NCoR knockout decreases PPARγ phosphorylation and enhances PPARγ activity and insulin sensitivity. Cell. 2011, 147, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.S.; Ryu, D.; Maida, A.; Wang, X.; Evans, R.M.; Schoonjans, K.; et al. Phosphorylation of the nuclear receptor corepressor 1 by protein kinase B switches its corepressor targets in the liver in mice. Hepatology. 2015, 62, 1606–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astapova, I.; Ramadoss, P.; Costa-e-Sousa, R.H.; Ye, F.; Holtz, K.A.; Li, Y.; et al. Hepatic nuclear corepressor 1 regulates cholesterol absorption through a TRβ1-governed pathway. J Clin Invest. 2014, 124, 1976–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Spann, N.J.; Kaikkonen, M.U.; Lu, M.; Oh, D.Y.; Fox, J.N.; et al. NCoR repression of LXRs restricts macrophage biosynthesis of insulin-sensitizing omega 3 fatty acids. Cell. 2013, 155, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner, P.; Choi, S.H.; Almazan, F.; Benner, C.; Huang, W.; Diehl, C.J.; et al. Low doses of lipopolysaccharide and minimally oxidized low-density lipoprotein cooperatively activate macrophages via nuclear factor kappa B and activator protein-1: possible mechanism for acceleration of atherosclerosis by subclinical endotoxemia. Circ Res. 2010, 107, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppi, S.; Nusser-Stein, S.; Blyszczuk, P.; Wang, X.; Jomard, A.; Marzolla, V.; et al. Macrophage NCOR1 protects from atherosclerosis by repressing a pro-atherogenic PPARγ signature. Eur Heart J. 2020, 41, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.M. CD36, a scavenger receptor implicated in atherosclerosis. Exp Mol Med. 2014, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, R.L.; Febbraio, M. CD36, a scavenger receptor involved in immunity, metabolism, angiogenesis, and behavior. Sci Signal. 2009, 2, re3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Santibanez-Koref, M.; Polvikoski, T.; Birchall, D.; Mendelow, A.D.; Keavney, B. Increased expression of fatty acid binding protein 4 and leptin in resident macrophages characterises atherosclerotic plaque rupture. Atherosclerosis. 2013, 226, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, K.D.; Bardwell, V.J. The BCL-6 POZ domain and other POZ domains interact with the co-repressors N-CoR and SMRT. Oncogene. 1998, 17, 2473–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, M.G.; Oswald, E.; Yu, W.; Xue, F.; MacKerell, A.D.; Jr Melnick, A.M. The Expanding Role of the BCL6 Oncoprotein as a Cancer Therapeutic Target. Clin Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barish, G.D.; Yu, R.T.; Karunasiri, M.S.; Becerra, D.; Kim, J.; Tseng, T.W.; et al. The Bcl6-SMRT/NCoR cistrome represses inflammation to attenuate atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Feng, D.; Fang, B.; Mullican, S.E.; You, S.H.; Lim, H.W.; et al. Deacetylase-independent function of HDAC3 in transcription and metabolism requires nuclear receptor corepressor. Mol Cell. 2013, 52, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenghat, T.; Meyers, K.; Mullican, S.E.; Leitner, K.; Adeniji-Adele, A.; Avila, J.; et al. Nuclear receptor corepressor and histone deacetylase 3 govern circadian metabolic physiology. Nature. 2008, 456, 997–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truman, L.A.; Bentley, K.L.; Smith, E.C.; Massaro, S.A.; Gonzalez, D.G.; Haberman, A.M.; et al. ProxTom lymphatic vessel reporter mice reveal Prox1 expression in the adrenal medulla, megakaryocytes, and platelets. Am J Pathol. 2012, 180, 1715–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, K.; Urano, T.; Watabe, T.; Ouchi, Y.; Inoue, S. PROX1 suppresses vitamin K-induced transcriptional activity of Steroid and Xenobiotic Receptor. Genes Cells. 2011, 16, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, H.; Qin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J. Prox1 directly interacts with LSD1 and recruits the LSD1/NuRD complex to epigenetically co-repress CYP7A1 transcription. PLoS One. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, Y.; Jetten, A.M. Prospero-related homeobox 1 (Prox1) functions as a novel modulator of retinoic acid-related orphan receptors αand γmediated transactivation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 6992–7008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffensen, K.R.; Holter, E.; Båvner, A.; Nilsson, M.; Pelto-Huikko, M.; Tomarev, S.; et al. Functional conservation of interactions between a homeodomain cofactor and a mammalian FTZ-F1 homologue. EMBO Rep. 2004, 5, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Qin, J.; Gao, D.M.; Jiang, Q.F.; Zhou, Q.; Kong, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Prosperorelated homeobox (Prox1) is a corepressor of human liver receptor homolog-1 and suppresses the transcription of the cholesterol 7-alpha-hydroxylase gene. Mol Endocrinol. 2004, 18, 2424–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kamiya, A.; Kakinuma, S.; Onodera, M.; Miyajima, A.; Nakauchi, H. Prospero-related homeobox 1 and liver receptor homolog 1 coordinately regulate long-term proliferation of murine fetal hepatoblasts. Hepatology. 2008, 48, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, S.; Oosterveer, M.H.; Mataki, C.; Xu, P.; Lemos, V.; Havinga, R.; et al. SUMOylation-dependent LRH-1/PROX1 interaction promotes atherosclerosis by decreasing hepatic reverse cholesterol transport. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefèvre, L.; Authier, H.; Stein, S.; Majorel, C.; Couderc, B.; Dardenne, C.; et al. LRH-1 mediates anti-inflammatory and antifungal phenotype of IL-13-activated macrophages through the PPARγ ligand synthesis. Nat Commun. 2015, 6, 6801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.; Schoonjans, K. Molecular basis for the regulation of the nuclear receptor LRH-1. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015, 33, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, S.; Lemos, V.; Xu, P.; Demagny, H.; Wang, X.; Ryu, D.; et al. Impaired SUMOylation of nuclear receptor LRH-1 promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2017, 127, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Oosterveer, M.H.; Stein, S.; Demagny, H.; Ryu, D.; Moullan, N.; et al. LRH-1-dependent programming of mitochondrial glutamine processing drives liver cancer. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Chinpaisal, C.; Wei, L.N. Cloning and characterization of mouse RIP140, a corepressor for nuclear orphan receptor TR2. Mol Cell Biol. 1998, 18, 6745–6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nautiyal, J.; Christian, M.; Parker, M.G. Distinct functions for RIP140 in development, inflammation, and metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2013, 24, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.C.; Tsui, Y.C.; Feng, X.; Greaves, D.R.; Wei, L.N. NF-κB-mediated degradation of the coactivator RIP140 regulates inflammatory responses and contributes to endotoxin tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2012, 13, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.W.; Liu, P.S.; Adhikari, N.; Hall, J.L.; Wei, L.N. RIP140 contributes to foam cell formation and atherosclerosis by regulating cholesterol homeostasis in macrophages. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015, 79, 287–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Gao, H.; Yue, Z.; Liu, Z.; et al. RIP140 triggers foamcell formation by repressing ABCA1/G1 expression and cholesterol efflux via liver X receptor. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Yahagi, N.; Aita, Y.; Murayama, Y.; Sawada, Y.; Piao, X.; et al. KLF15 Enables Rapid Switching between Lipogenesis and Gluconeogenesis during Fasting. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 2373–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, B.; Hallberg, M.; Seth, A.; Woods, A.; White, R.; Parker, M.G. The nuclear receptor cofactor, receptor-interacting protein 140, is required for the regulation of hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism by liver X receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2007, 21, 2687–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liao, X.; Sangwung, P.; Prosdocimo, D.A.; Zhou, G.; et al. Kruppel-like factor 15 is critical for vascular inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2013, 123, 4232–4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmesser, U.; Poller, W.; Tsimikas, S.; Most, P.; Paneni, F.; Lüscher, T.F. From traditional pharmacological towards nucleic acid-based therapies for cardiovascular diseases. Eur Heart J. 2020, 41, 3884–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, P.N. Molecular biology of atherosclerosis. Physiol Rev. 2013, 93, 1317–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, K.; White, S.; Borodovsky, A.; Bettencourt, B.R.; Strahs, A.; Clausen, V.; et al. A Highly Durable RNAi Therapeutic Inhibitor of PCSK9. N Engl J Med. 2017, 376, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2022 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.