Double Trouble—A Case of Atrial Fibrillation and Pulmonary Embolism

Abstract

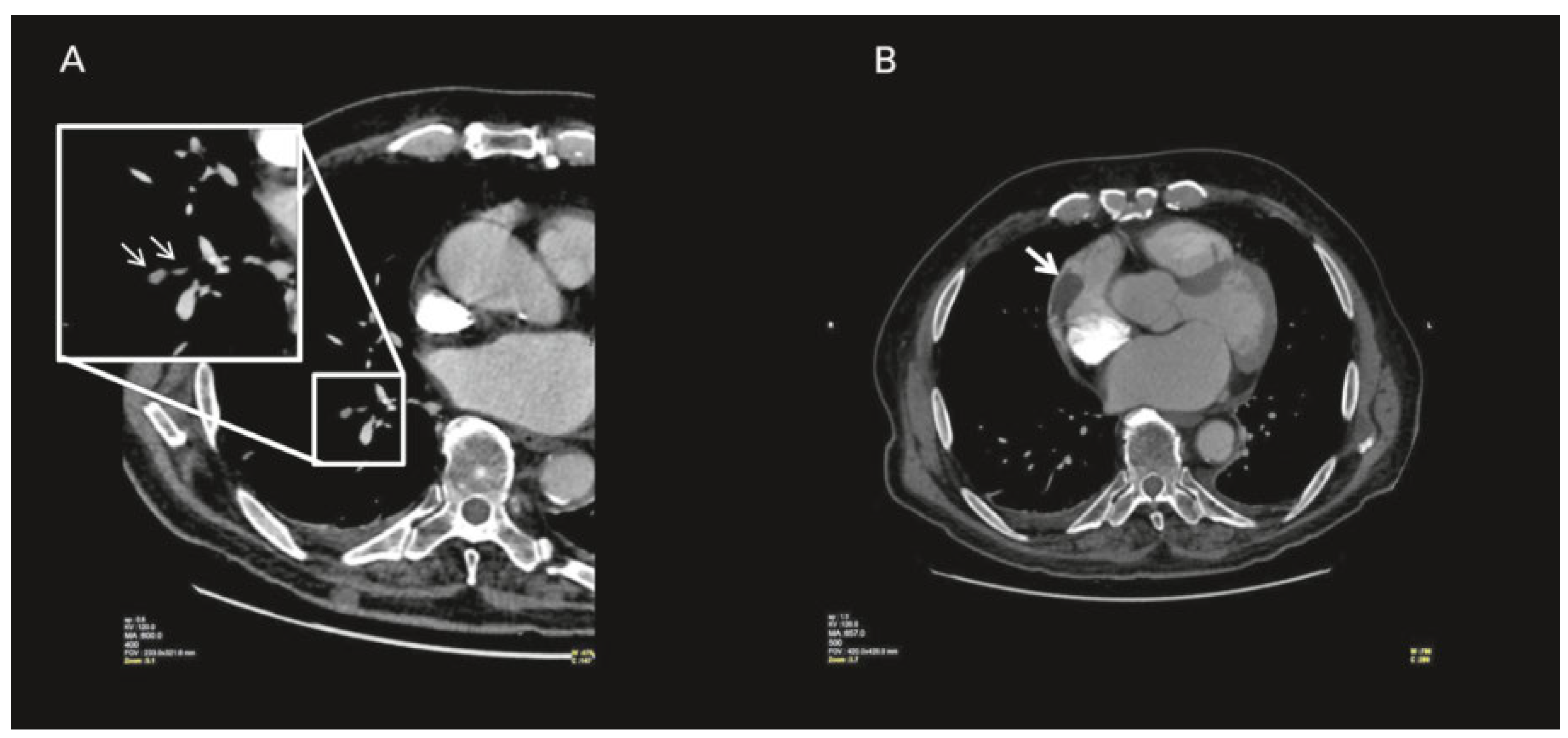

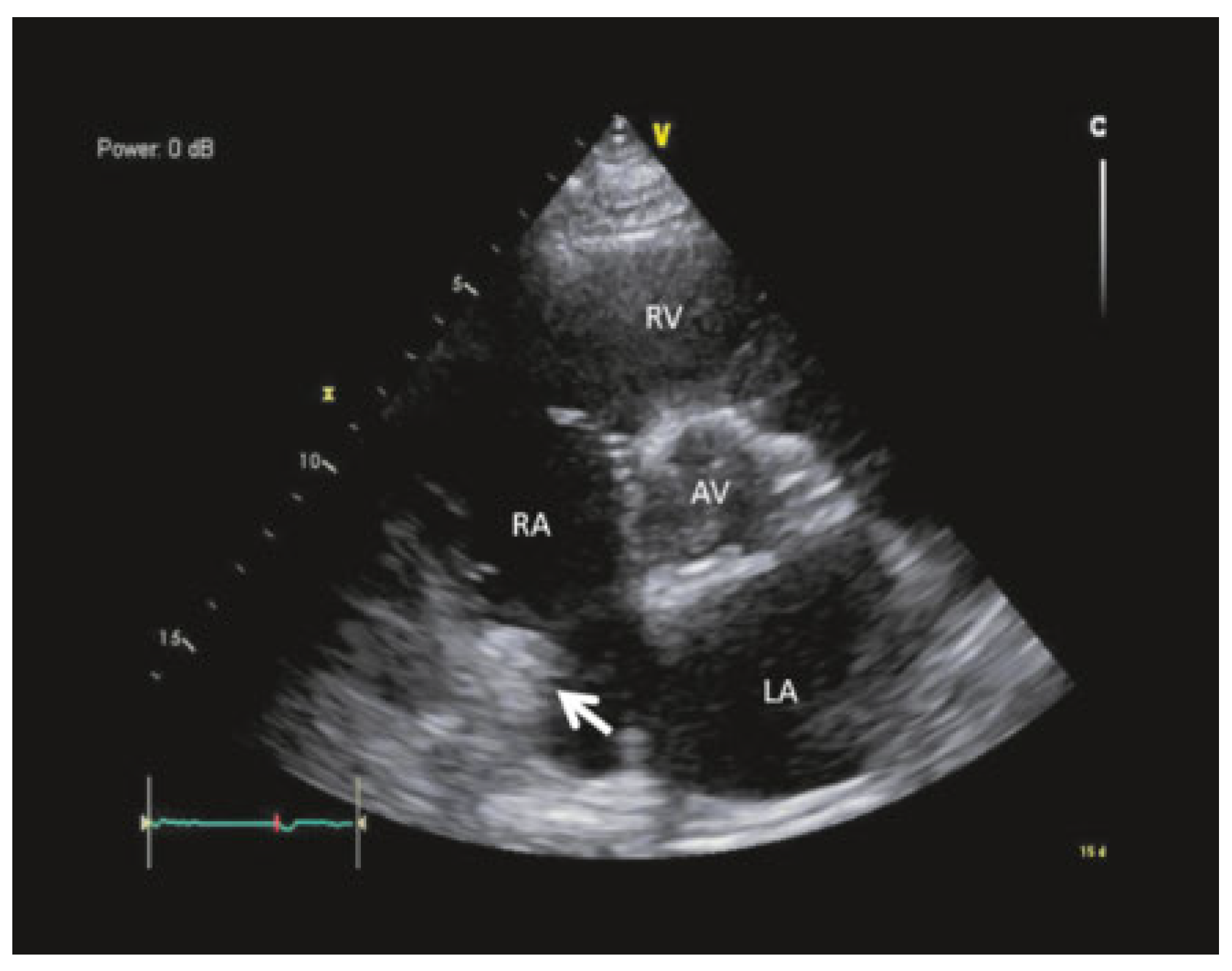

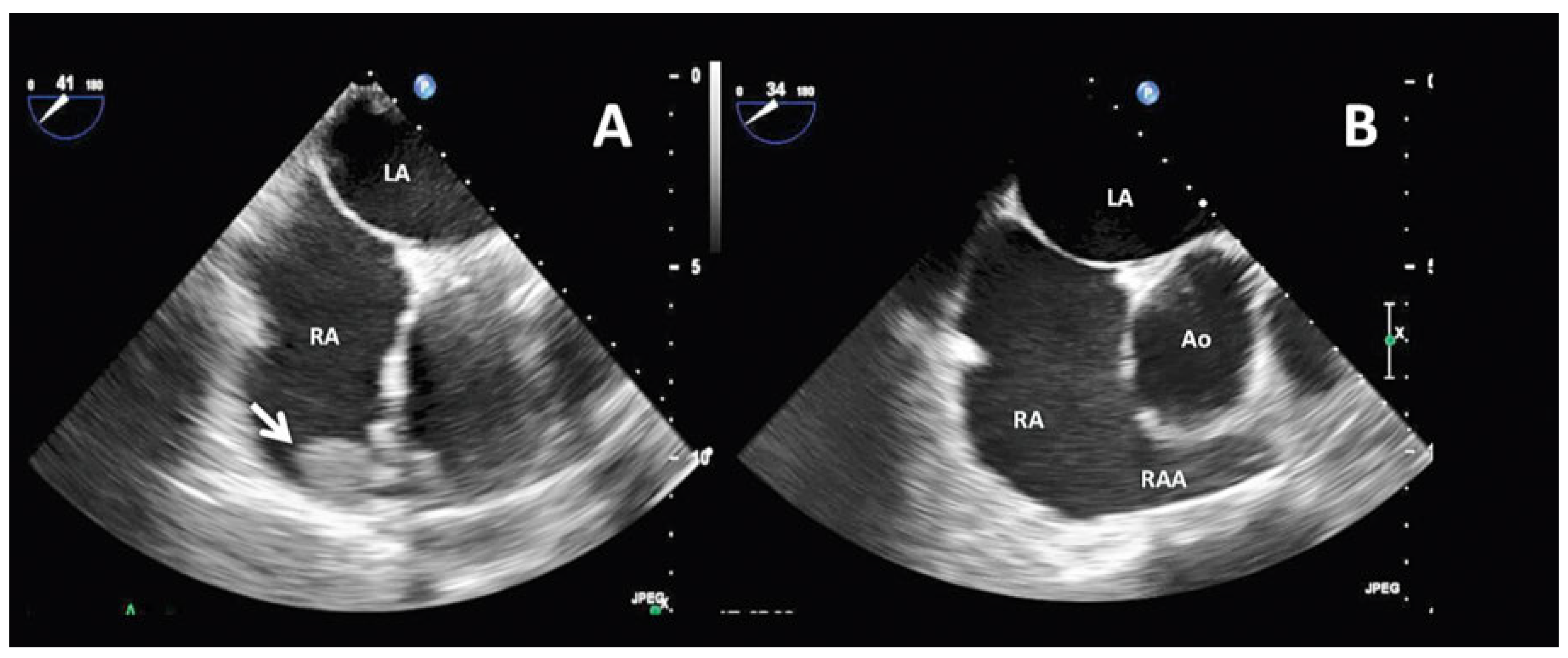

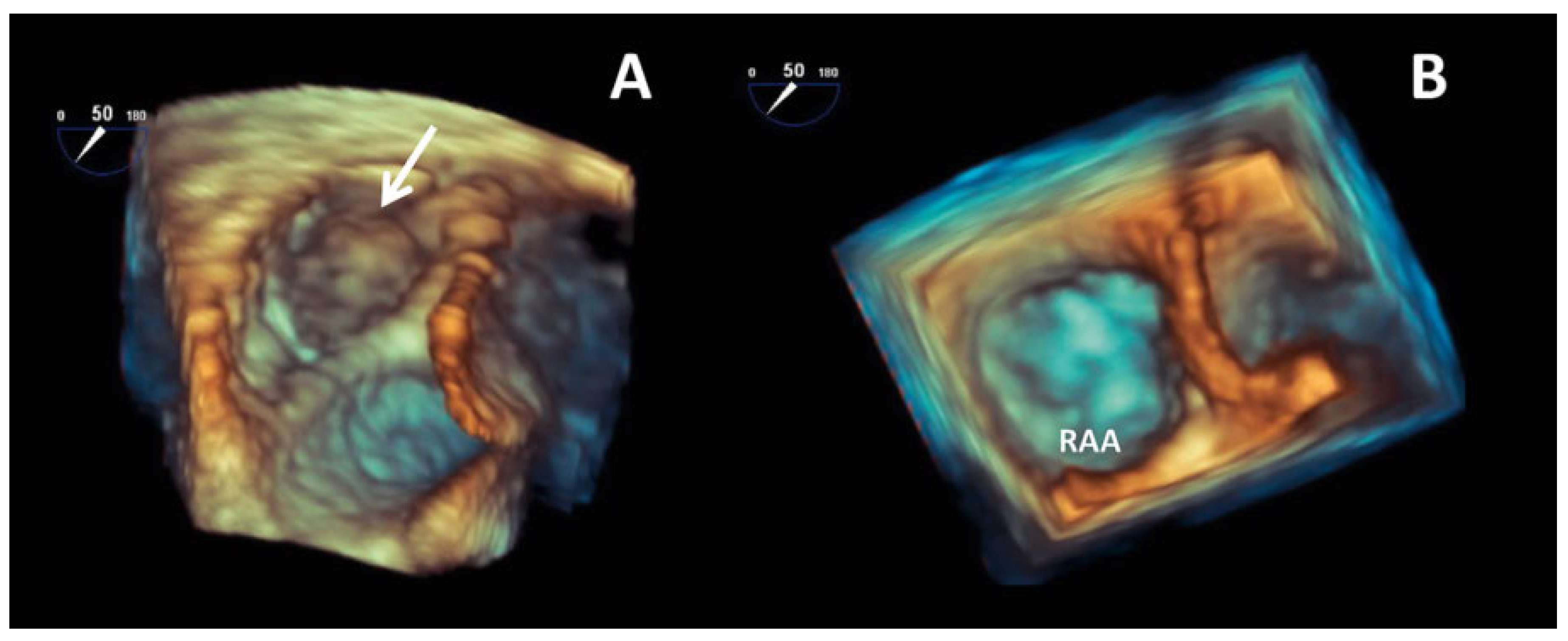

Case report

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manning, W.J.; Silverman, D.I.; Waksmonski, C.A.; Oettgen, P.; Douglas, P.S. Prevalence of residual left atrial thrombi among patients with acute thromboembolism and newly recognized atrial fibrillation. Arch. Intern. Med. 1995, 155, 2193–2198. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7487241. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Divitiis, M.; Omran, H.; Rabahieh, R.; Rang, B.; Illien, S.; Schimpf, R.; et al. Right atrial appendage thrombosis in atrial fibrillation: its frequency and its clinical predictors. Am. J. Cardiol. 1999, 84, 1023–1028. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10569657. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, W.J.; Silverman, D.I.; Keighley, C.S.; Oettgen, P.; Douglas, P.S. Transesophageal echocardiographically facilitated early cardioversion from atrial fibrillation using short-term anticoagulation: final results of a prospective 4.5-year study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1995, 25, 1354–1361. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7722133. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cresti, A.; García-Fernández, M.A.; Miracapillo, G.; Picchi, A.; Cesareo, F.; Guerrini, F.; et al. Frequency and significance of right atrial appendage thrombi in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2014, 27, 1200–1207. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25240491. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinoda, K.; Hayashi, S.; Fukuoka, D.; Torii, R.; Watanabe, T.; Nakano, T. Structural Comparison between the Right and Left Atrial Appendages Using Multidetector Computed Tomography. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 6492183. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27900330. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikdeli, B.; Abouziki, M.D.; Lip, G.Y.H. Erratum: Pulmonary Embolism and Atrial Fibrillation: Two Sides of the Same Coin? A Systematic Review. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2017. ISSN 1098-9064.: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28427092. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28427092.

- Barrios, D.; Rosa-Salazar, V.; Morillo, R.; Nieto, R.; Fernández, S.; Zamorano, J.L.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Right Heart Thrombi in Patients With Acute Symptomatic Pulmonary Embolism: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Chest. 2017, 151, 409–416. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27746202. [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.

Share and Cite

Valitona, V.; Brugger, N.; Graf, D.; Cook, S.; Arroyo, D. Double Trouble—A Case of Atrial Fibrillation and Pulmonary Embolism. Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 20, 310. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2017.00531

Valitona V, Brugger N, Graf D, Cook S, Arroyo D. Double Trouble—A Case of Atrial Fibrillation and Pulmonary Embolism. Cardiovascular Medicine. 2017; 20(12):310. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2017.00531

Chicago/Turabian StyleValitona, Valerian, Nicolas Brugger, Denis Graf, Stéphane Cook, and Diego Arroyo. 2017. "Double Trouble—A Case of Atrial Fibrillation and Pulmonary Embolism" Cardiovascular Medicine 20, no. 12: 310. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2017.00531

APA StyleValitona, V., Brugger, N., Graf, D., Cook, S., & Arroyo, D. (2017). Double Trouble—A Case of Atrial Fibrillation and Pulmonary Embolism. Cardiovascular Medicine, 20(12), 310. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2017.00531