Case description

A 69-year-old Caucasian woman presented to her general practitioner with new onset fatigue and rapidly progressive dyspnoea on exertion. Upon physical examination the patient was afebrile, blood pressure was 116/72 mm Hg, pulse rate 76/min and respiration rate 12/min. Heart sounds were normal, but a new, 3/6, crescendo–decrescendo systolic murmur, which increased during deep inspiration and was maximal along the left sternal border, was noted. Laboratory studies of electrolytes, renal function, liver and cardiac enzymes, acute phase reactants and complete blood count were within normal limits, as were a 12-lead ECG and a chest radiograph.

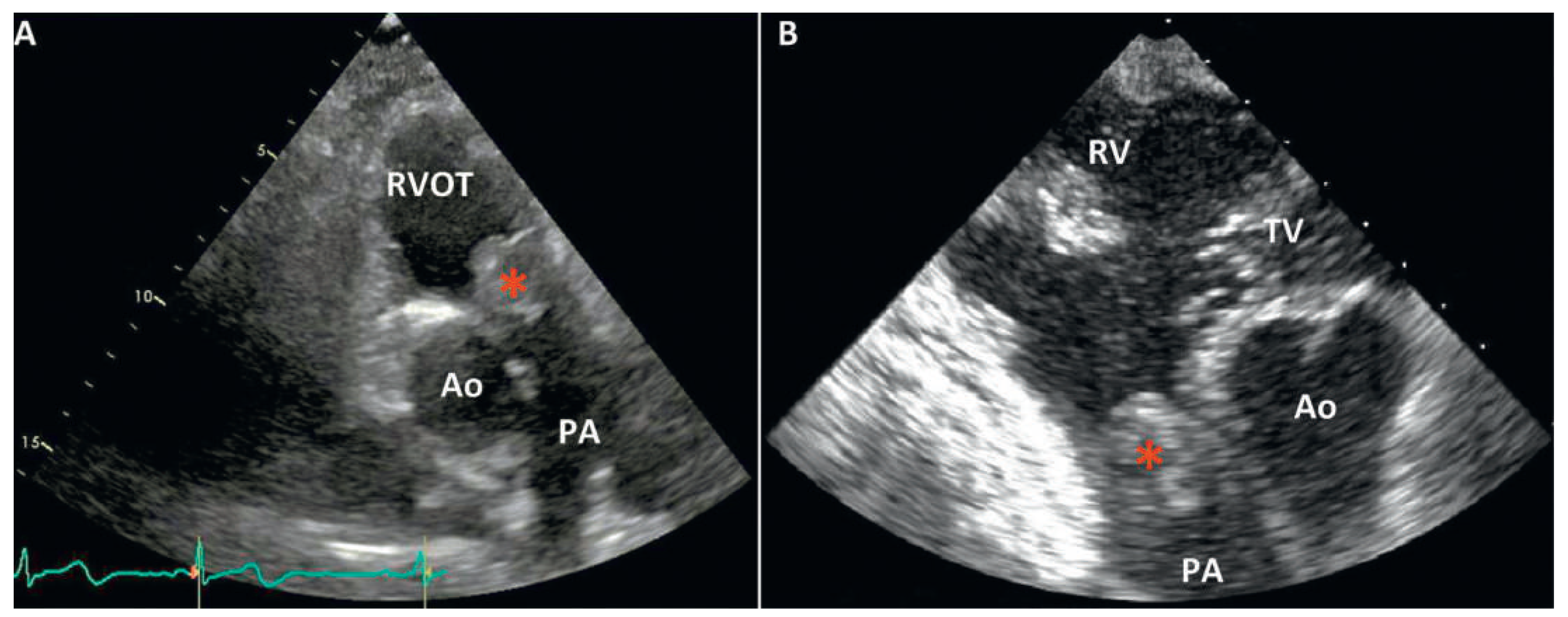

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed a moderate pulmonary valve stenosis caused by a globular mass protruding into the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) during diastole (

Figure 1). The maximum pulmonary pressure gradient was measured at 42 mm Hg (mean 30 mm Hg). Left as well as right ventricle size and function were normal.

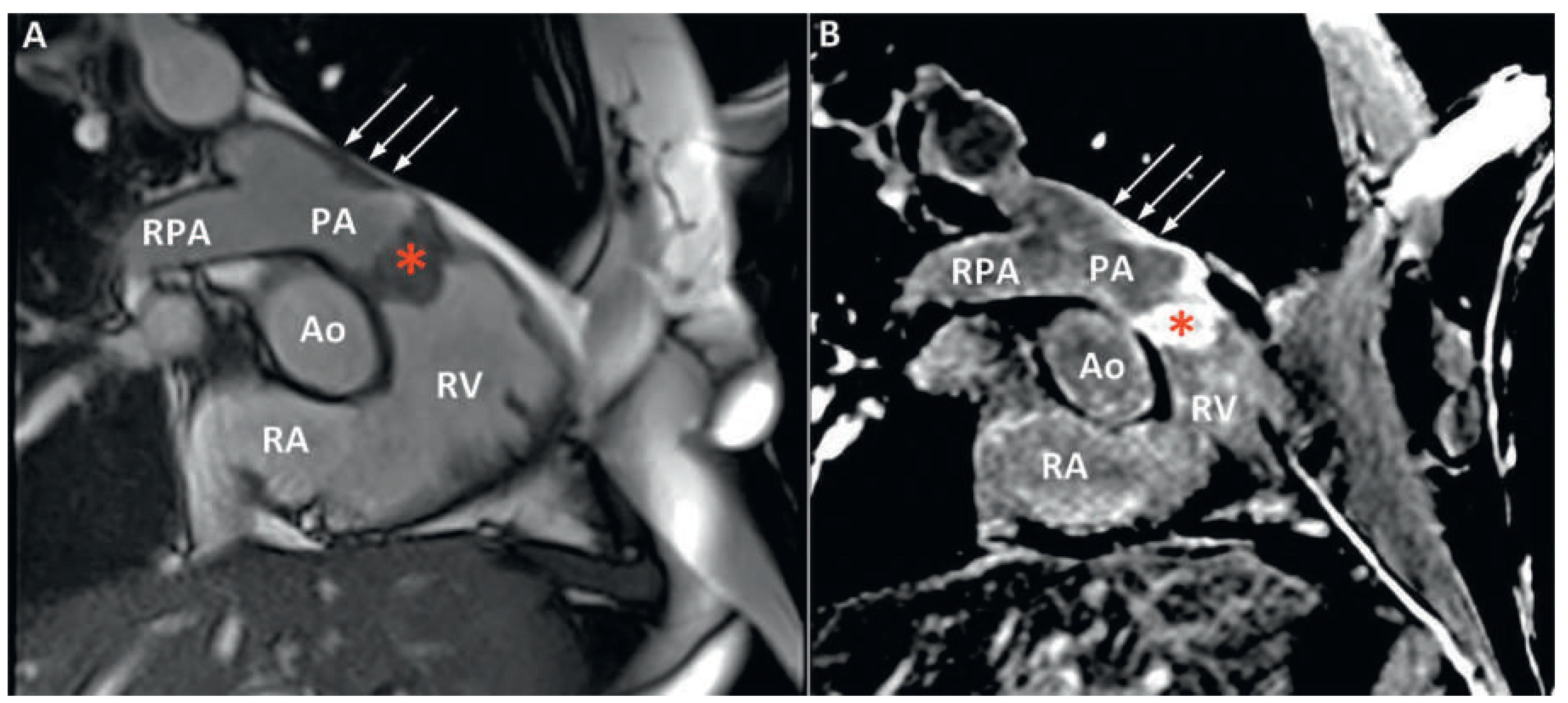

The patient was promptly referred to our institution where cardiac computed tomography (CT) revealed a 25 × 35 × 24 mm mass attached to the RVOT and extending into the pulmonary trunk through the pulmonary valve (

Figure 2). After intravenous injection of 60–80 ml iodinated contrast material, late image acquisition showed inhomogeneous enhancement of the mass and mural enhancement of the pulmonary trunk suggestive of infiltration. This technique in the context of cardiac CT consists of acquiring images 60 seconds after CT angiography in order to optimise tissue enhancement. Fludeoxyglucose (18F) positron emission tomography-CT (18F-FDG PET-CT) revealed mild metabolic activity of the mass, with no signs of metastasis (

Figure 3). Finally, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed proximal extension of the valve mass, 4 cm towards the pulmonary trunk, without apparent invasion of the bifurcation (

Figure 4). A hyperintense signal in T2-weighted images indicated oedema, whereas moderate signal-enhancement during resting perfusion suggested rich vascularisation. Intense signals on gadolinium enhancement sequences suggested rich extracellular content (fibrosis or extracellular matrix), but no significant necrosis (

Figure 5).

A provisory diagnosis of intracardiac malignancy was made on clinical (rapid installation of symptoms) and imaging (vascular infiltrative mass) grounds, and endovascular biopsy was attempted. The procedure was uneventful, but yielded limited material for histology. The case was discussed by a multidisciplinary panel involving cardiologists, radiologists and a cardiothoracic surgeon, and surgery was decided on. The time delay from first diagnosis on TTE to the operation was 22 days. During the procedure, a bulky, white mass, densely adherent and infiltrating the pulmonary valve and all of the pulmonary infundibulum was identified and removed, along with the deformed pulmonary valve, part of the RVOT, as well as most of the pulmonary trunk as proximally as possible to the bifurcation. An autologous graft was used to replace the valve; the right ventricle was then anastomosed to the distal part of the pulmonary artery. Postoperative histology revealed a mesenchymal tumour consisting of highly atypical spindle cells without specific differentiation (

Figure 6) [1]. Given the retrograde extension of the mass and the possibility of residual fragments very low inside the RVOT, the patient was referred for adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy after six weeks of convalescence in a cardiac rehabilitation centre.

Discussion

Our case highlights the major impediments encountered during management of these rare and often fatal intracardiac tumours; from timely and accurate diagnosis to surgical resection and adjuvant care, pulmonary artery sarcomas (PAS) represent a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for cardiologists, radiologists, cardiac surgeons and oncologists.

Typical onset age is 45–55 years with a female to male ratio of 2:1. The tumour typically arises within the pulmonary trunk and spreads into the pulmonary arteries. Embryologically, it originates from the bulbus cordis, a structure that later gives birth to both the RVOT and pulmonary trunk, which could, in our case, explain valve involvement and RVOT extension. As with the majority of intracardiac tumours, presentation is non-specific, with dyspnoea on exertion, chest or back pain, cough and haemoptysis being common symptoms. In many cases, the clinical presentation mimics chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, and in advanced stages constitutional symptoms appear. Physical examination remains unremarkable until late. Our case is unique in the sense that it presented as a new unfamiliar murmur that alarmed the primary physician. Such a finding is extremely rare and highlights the paramount importance of good auscultation skills and a clinical acumen. A new harsh systolic murmur that increases with inspiration indicates pulmonary stenosis and warrants further investigation with echocardiography. TTE may show an increased gradient across a narrowed RVOT [2]. The presence of a pedunculated lesion arising from the RVOT, or pulmonary valve or trunk should always raise suspicion of PAS [3] and prompt a thoracic CT or a cardiac MRI.

CT findings can be misleading in over 50% of cases, as PAS is confused with the far more common condition of central pulmonary embolism. Both entities present with a filling defect in the pulmonary arteries. Suggestive of PAS are an inhomogeneous, soft tissue density, with the filling defect occupying the entire lumen of the pulmonary trunk, along with delayed contrast enhancement on angiography [4]. Once suspicion is raised, PET-CT and MRI are helpful to differentiate fully the mass. Preoperative histological diagnosis is generally not possible although it should be attempted through CT-guided transthoracic aspiration, transvenous catheter biopsy or transbronchial biopsy. In most cases definitive diagnosis is made only during surgery or at autopsy. Surgery remains the cornerstone of management, offering definite diagnosis, clinical improvement and the best prognosis [5]. Even if curative resection is not possible, palliative resection can provide symptom relief by restoring haemodynamics. Reported interventions range from bilateral pneumonectomy, pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA) with or without pneumonectomy and with or without reconstruction of the pulmonary artery to debulking and palliative stenting. Regarding adjuvant therapy, combined chemoand radiotherapy should be adopted in nearly every case to extend palliation. Overall, PAS represents a fatal disease, with a mean survival time without surgical intervention of 1.5 months. Survival of 36.5 ± 20.2 months has been reported for patients benefiting from a “curative” resection while 11 ± 3 months for those undergoing “incomplete” resection [5].

In conclusion, it is important that physicians recognise the clinical features associated with PAS and include it as a differential diagnosis in the appropriate setting. Early referral for multidisciplinary management in a tertiary centre offers the only chance for prolonged survival and improved quality of life.

Disclosures

No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.