Short Breath, Small Vessels and Big Heart—An Unusual Suspect

Abstract

Introduction

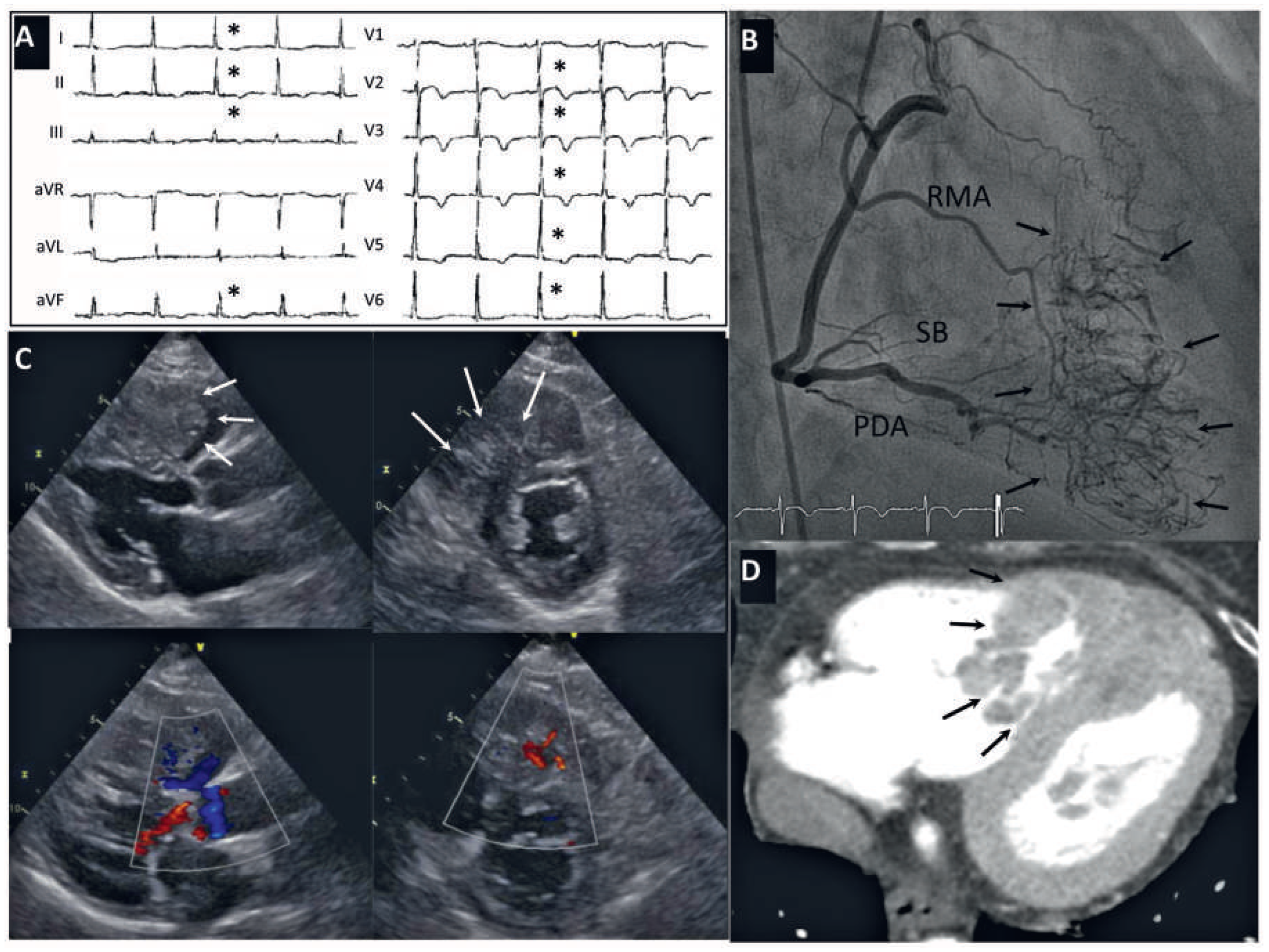

Case report

Discussion

Disclosures

References

- Goldberg, A.D.; Blankstein, R.; Padera, R.F. Tumors metastatic to the heart. Circulation. 2013, 128, 1790–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussani, R.; De Giorgio, F.; Abbate, A.; Silvestri, F. Cardiac metastases. J Clin Pathol. 2007, 60, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, J.; Nakayama, J.; Yoshimura, Y.; Ikeda, U. Clinical classification of cardiovascular tumors and tumor like lesions, and its incidences. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013, 61, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.C.; Lui, K.W.; Ho, M.C.; Fan, S.Z.; Chao, A. Right ventricular exclusion for hepatocellular carcinoma metastatic to the heart. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, E.; Kiuchi, K.; Takayama, M.; Takano, T.; Tabata, M.; Aramaki, T.; et al. Effectiveness of transcoronary chemoembolization for metastatic right ventricular tumor derived from hepatocellular carcinoma. Chest 2000, 117, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.

Share and Cite

Grandjean, T.; Brugger, N.; Cook, S.; Baeriswyl, G. Short Breath, Small Vessels and Big Heart—An Unusual Suspect. Cardiovasc. Med. 2015, 18, 220. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2015.00343

Grandjean T, Brugger N, Cook S, Baeriswyl G. Short Breath, Small Vessels and Big Heart—An Unusual Suspect. Cardiovascular Medicine. 2015; 18(7-8):220. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2015.00343

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrandjean, Thierry, Nicolas Brugger, Stéphane Cook, and Gérard Baeriswyl. 2015. "Short Breath, Small Vessels and Big Heart—An Unusual Suspect" Cardiovascular Medicine 18, no. 7-8: 220. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2015.00343

APA StyleGrandjean, T., Brugger, N., Cook, S., & Baeriswyl, G. (2015). Short Breath, Small Vessels and Big Heart—An Unusual Suspect. Cardiovascular Medicine, 18(7-8), 220. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2015.00343