Transcoronary Alcohol Ablation—On Behalf of Three Cases with Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy

Abstract

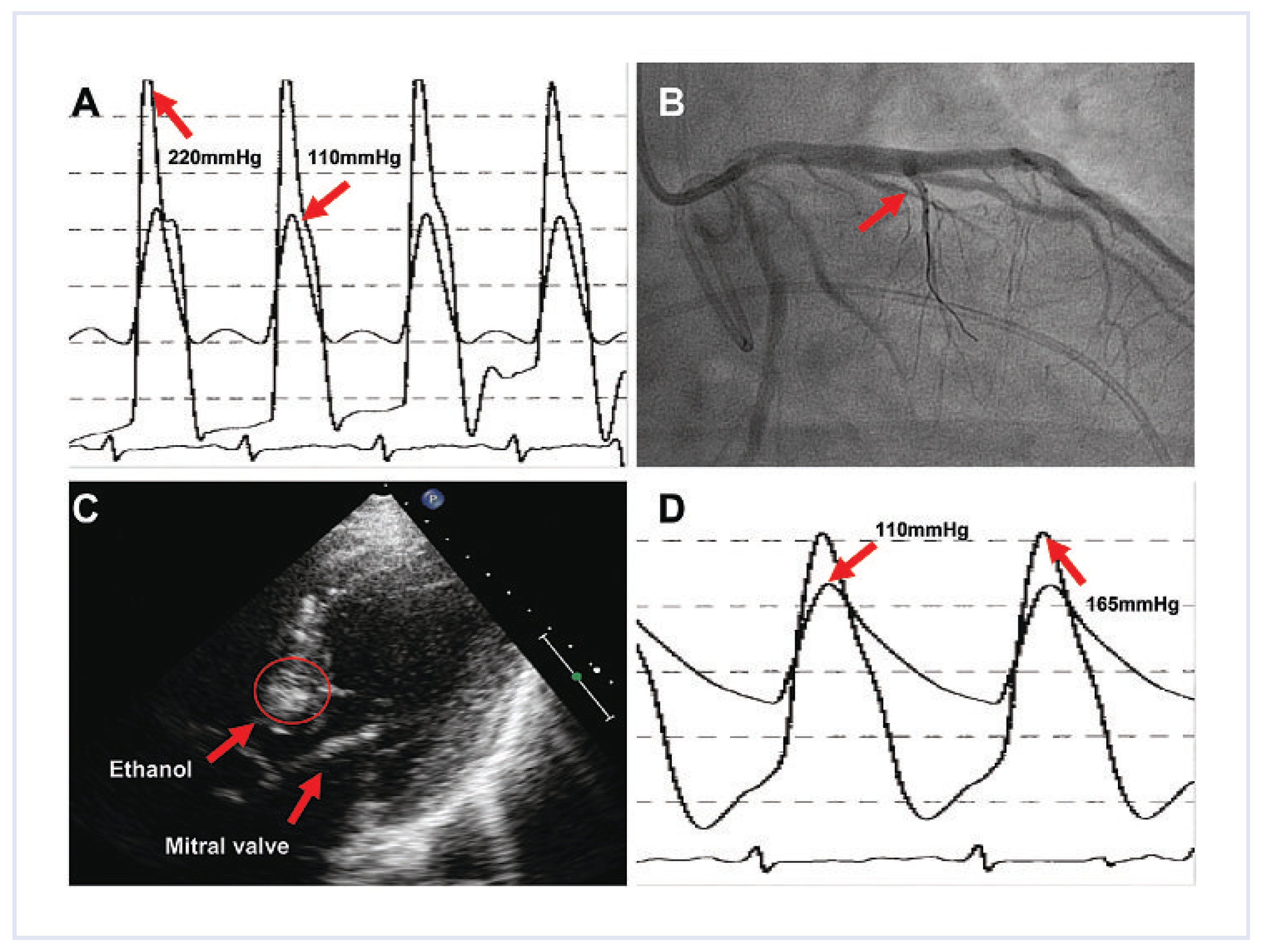

Case 1

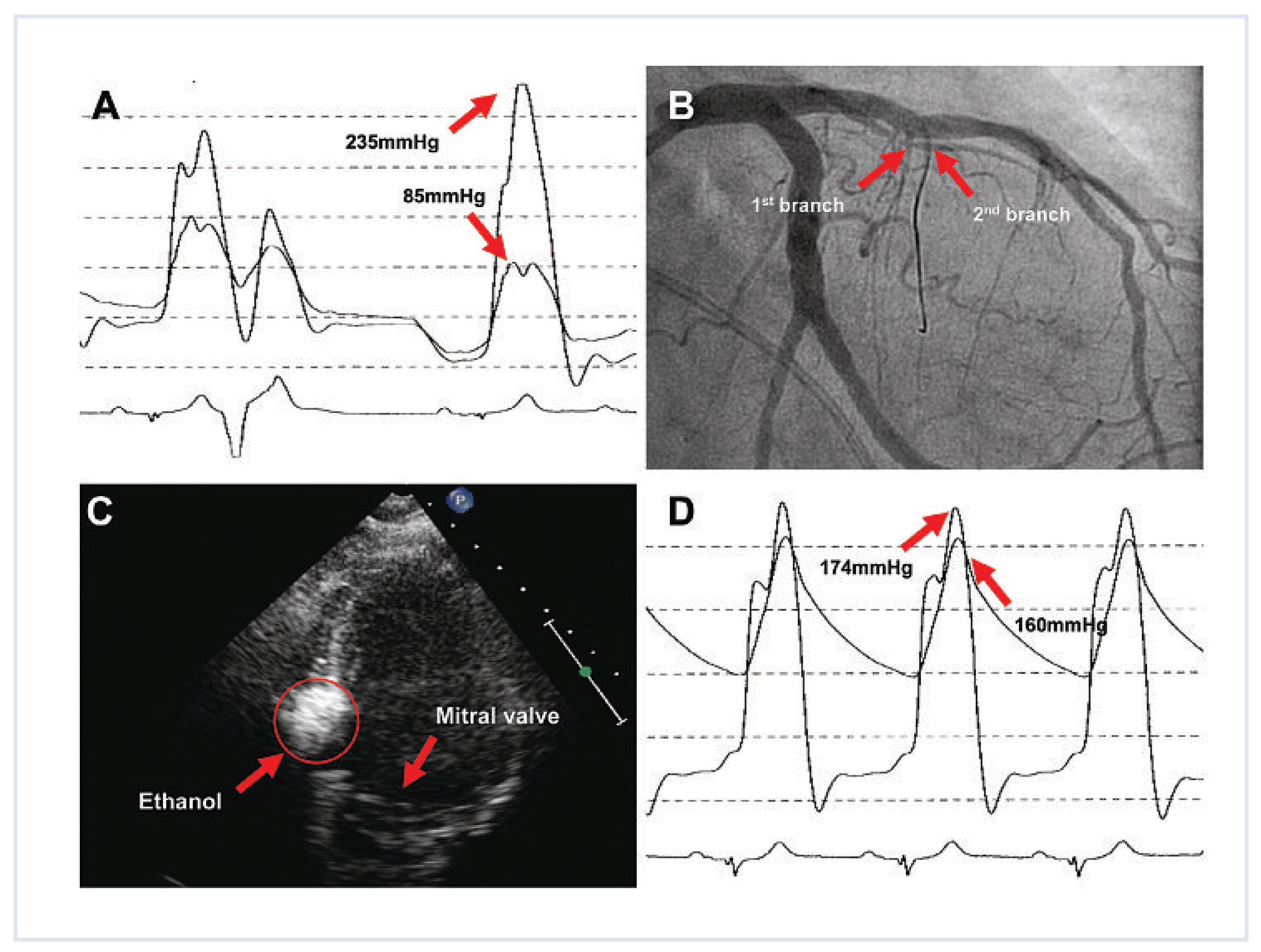

Case 2

Case 3

Discussion

Funding/Potential Competing Interests

References

- Maron, M.S.; Olivotto, I.; Betocchi, S.; Casey, S.A.; Lesser, J.R.; Losi, M.A.; et al. Effect of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction on clinical outcome in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2003, 348, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, R.; Sigwart, U. Current concepts of the pathogenesis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005, 112, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fifer, M.A.; Sigwart, U. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: Alcohol septal ablation. Eur Heart J. 2011, 32, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, B.J.; Shen, W.K.; Link, M.S.; Epstein, A.E.; Almquist, A.K.; Daubert, J.P.; et al. Efficacy of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for the prevention of sudden death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000, 342, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiler, C.; Hess, O.M.; Schoenbeck, M.; Turina, J.; Jenni, R.; Turina, M.; et al. Long-term follow-up of medical versus surgical therapy for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A retrospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991, 17, 634–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sigwart, U. Non-surgical myocardial reduction for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 1995, 346, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Olivotto, I.; Ommen, S.R.; Maron, M.S.; Cecchi, F.; Maron, B.J. Surgical myectomy versus alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Will there ever be a randomized trial? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007, 50, 831–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.X.; Shiota, T.; Lever, H.M.; Kapadia, S.R.; Sitges, M.; Rubin, D.N.; et al. Outcome of patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy after percutaneous transluminal septal myocardial ablation and septal myectomy surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001, 38, 1994–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Ommen, S.R.; Lakkis, N.M.; Killip, D.; Zoghbi, W.A.; Schaff, H.V.; et al. Comparison of ethanol septal reduction therapy with surgical myectomy for the treatment of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001, 38, 1701–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Desai, M.Y.; Smedira, N.; Lever, H.M.; Lytle, B.W.; et al. Updated meta-analysis of septal alcohol ablation versus myectomy for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010, 55, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.; Dokainish, H.; Lakkis, N.M. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy-alcohol septal ablation vs. myectomy: A meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2009, 30, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faber, L.; Seggewiss, H.; Gleichmann, U. Percutaneous transluminal septal myocardial ablation in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: Results with respect to intraprocedural myocardial contrast echocardiography. Circulation 1998, 98, 2415–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, O.M.; Sigwart, U. New treatment strategies for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: Alcohol ablation of the septum: The new gold standard? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004, 44, 2054–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fifer, M.A.; Sigwart, U. Controversies in cardiovascular medicine. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: Alcohol septal ablation. Eur Heart. J. 2011, 32, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, B.J. Controversies in cardiovascular medicine. Surgical myectomy remains the primary treatment option for severely symptomatic patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2007, 116, 196–206; discussion 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrenz, T.; Obergassel, L.; Lieder, F.; Leuner, C.; Strunk-Mueller, C.; Meyer, D.; Vilsendorf, Z.; et al. Transcoronary ablation of septal hypertrophy does not alter ICD intervention rates in high risk patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005, 28, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gietzen, F.H.; Leuner, C.J.; Raute-Kreinsen, U.; Dellmann, A.; Hegselmann, J.; Strunk-Mueller, C.; et al. Acute and long-term results after transcoronary ablation of septal hypertrophy (TASH). Catheter interventional treatment for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 1999, 20, 1342–1354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.; Dokainish, H.; Lakkis, N. Alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: A systematic review of published studies. J Interv Cardiol. 2006, 19, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.M.; Lakkis, N.M.; Franklin, J.; Spencer, W.H., 3rd; Nagueh, S.F. Predictors of outcome after alcohol septal ablation therapy in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2004, 109, 824–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, H.; Lawrenz, T.; Lieder, F.; Leuner, C.; Strunk-Mueller, C.; Obergassel, L.; et al. Survival after transcoronary ablation of septal hypertrophy in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (TASH): A 10 year experience. Clin Res Cardiol. 2008, 97, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2011 by the author. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.

Share and Cite

Breitenstein, A.; Alibegovic, J.; Hürlimann, D.; Biaggi, P.; Corti, R.; Lüscher, T.F. Transcoronary Alcohol Ablation—On Behalf of Three Cases with Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc. Med. 2011, 14, 290. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2011.01615

Breitenstein A, Alibegovic J, Hürlimann D, Biaggi P, Corti R, Lüscher TF. Transcoronary Alcohol Ablation—On Behalf of Three Cases with Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. Cardiovascular Medicine. 2011; 14(10):290. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2011.01615

Chicago/Turabian StyleBreitenstein, Alexander, Jasmina Alibegovic, David Hürlimann, Patric Biaggi, Roberto Corti, and Thomas F. Lüscher. 2011. "Transcoronary Alcohol Ablation—On Behalf of Three Cases with Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy" Cardiovascular Medicine 14, no. 10: 290. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2011.01615

APA StyleBreitenstein, A., Alibegovic, J., Hürlimann, D., Biaggi, P., Corti, R., & Lüscher, T. F. (2011). Transcoronary Alcohol Ablation—On Behalf of Three Cases with Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. Cardiovascular Medicine, 14(10), 290. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2011.01615