Case report

A 42-year-old South Asian male with type 2 diabetes under oral antidiabetics was referred for transcatheter closure of a residual ventricular septal defect (VSD) after surgical correction of a post myocardial infarction VSD. His past history was remarkable for a cryptogenic stroke seven years earlier with residual left-sided hemiparesis and upper motor neuron facial nerve palsy presumably due to a paradoxical embolism in the setting of a patent foramen ovale (PFO) grade III which had successfully been occluded percutaneously with an Amplatzer PFO Occluder (25 mm) (St. Jude-AGA Medical Corporation, Plymouth, MN, USA) at that time. In view of his age of 35 years an incidental coronary angiography had not been performed. We usually recommend incidental coronary angiography in men > 40 years and women > 50 years, particularly in the presence of risk factors.

Seven years later the patient presented to the emergency room complaining of left-sided chest pain and shortness of breath at rest with clinical features of acute pulmonary oedema. The electrocardiogram revealed subacute inferior Q-wave myocardial infarction. Coronary angiography showed single vessel disease with a complete occlusion of the posterolateral branch of the right coronary artery as the culprit lesion which was successfully treated with balloon angioplasty after failed thrombus aspiration. Ventriculography revealed a ventricular septal defect with a significant Qp:Qs shunt of 2 and a maximal diameter of 20 mm. After initial medical stabilisation with afterload reduction, the patient underwent surgical closure of the defect by a Gore-Tex patch (W.L. Gore & Associate Inc., Flagstaff, AZ, USA) two weeks after the complicated myocardial infarction.

Two months after cardiac surgery the patient was readmitted with light-headedness and dizziness but had no chest pain or shortness of breath. Physical examination revealed a grade IV high pitched pansystolic heart murmur. No fever or chills were documented. Transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) detected a residual VSD of 15 mm located at the apex with a left to right shunt, a peak instantaneous gradient of 30 mm Hg and an estimated Qp:Qs of >1.5. Left ventricular function was normal. The patient was referred for transcatheter closure of the significant residual defect.

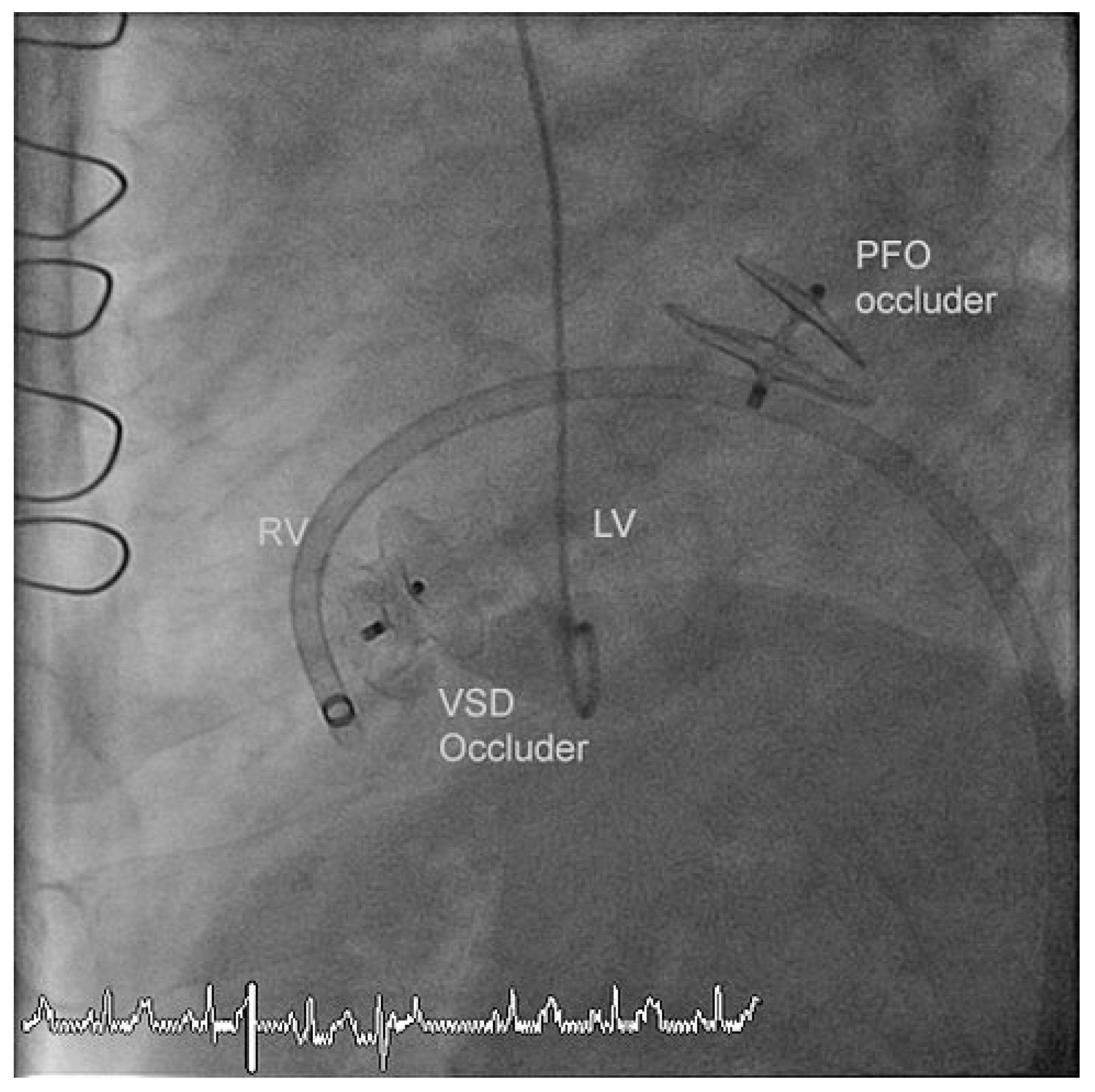

The residual VSD was identified with left ventricular contrast injection and the defect was crossed from the left ventricular side using a guide wire which was snared in the pulmonary artery and exteriorized thus creating an arteriovenous loop. The VSD was measured using a 34 mm sizing balloon (St. Jude-AGA) (

Figure 1). A 14 mm Amplatzer muscular VSD occluder (St. Jude-AGA) was implanted through an 8 F TorqVue sheath (St. Jude-AGA) inserted through the right femoral vein (

Figure 2). Adequate position was confirmed under fluoroscopy with contrast injection into the left ventricle (

Figure 3). The procedure was performed without TEE and under local anaesthesia.

At the same time coronary angiography detected a total (re-)occlusion of the posterior descending and the posterolateral branch of the right coronary artery and a significant stenosis of the distal right coronary artery which were treated with balloon angioplasty. The PFO Amplatzer Occluder implanted seven years earlier was free of residual shunt.

The patient was mobilized four hours after the procedure and discharged home the next day. Transthoracic echocardiography prior to discharge confirmed stable position of the VSD occluder and the previously implanted PFO occluder and detected no significant residual left-right ventricular shunt.

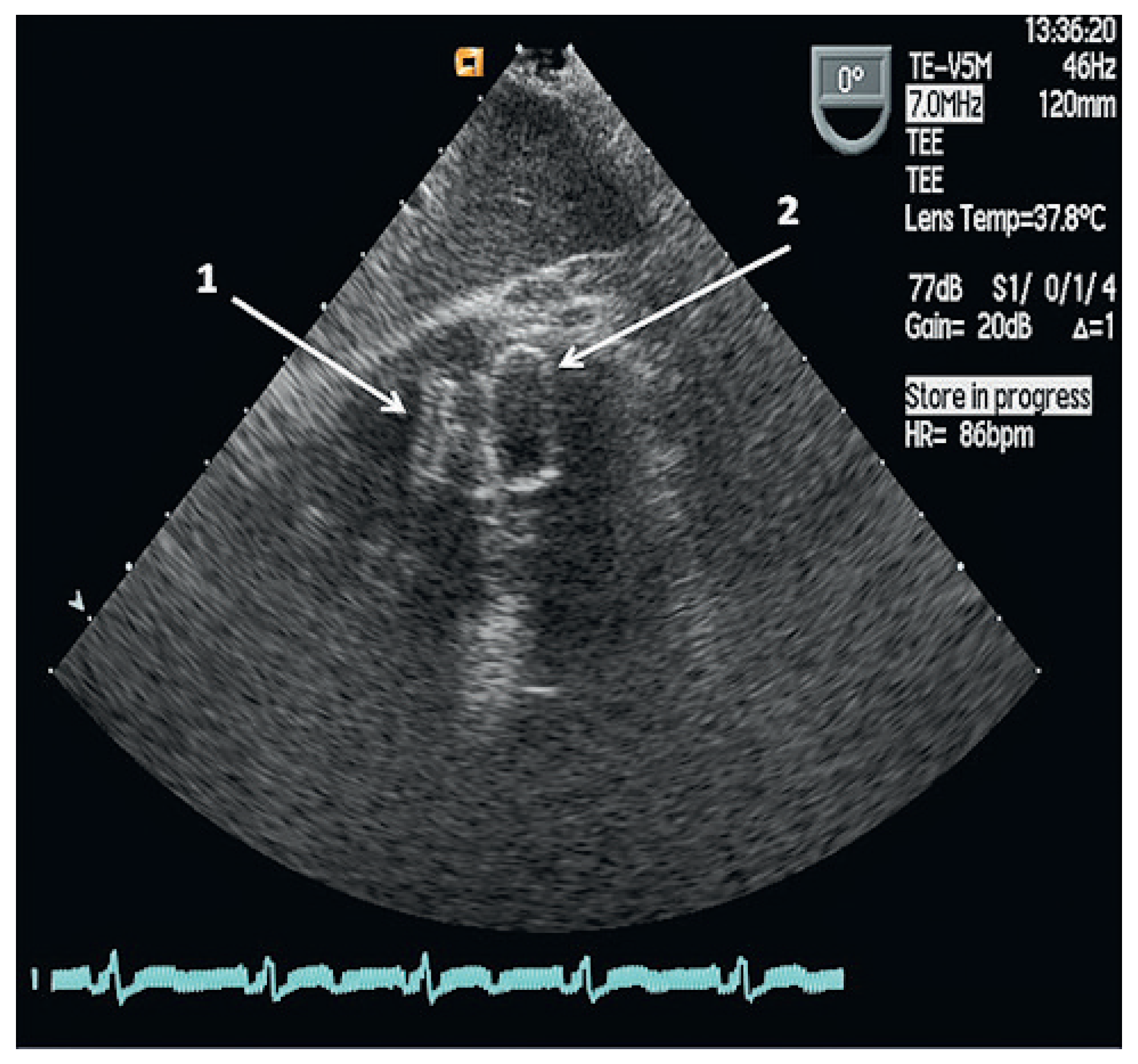

A TEE performed three months later detected a residual left-right ventricular shunt next to the VSD occluder in stable position. An additional transcatheter VSD closure was performed without sizing of the defect and a 14 × 5 mm Amplatzer Vascular Plug III (St. Jude-AGA) was aligned with the previous occluder through an 8 F TorqVue sheath inserted through the right femoral vein. He was discharged home the next day.

Three months later, a follow-up TEE demonstrated no residual left-right ventricular shunt and the two VSD occluders were aligned and in stable position (

Figure 4). Nine months after the last intervention the patient reported no shortness of breath and continued dual antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel.

Discussion

Post myocardial infarction VSDs are located in the muscular region of the ventricular septum and may sometimes be multiple with typically irregular margins. They represent ruptures in a necrotic lake or aneurysm of the myocardium prone to further expansion [

1,

2].

Surgical closure of a post infarction VSD remains the first choice especially in younger individuals but it carries an operative mortality of >30% [

3]. A post procedural residual shunt has been observed in approximately 20% and can be due to inadequate exposure, patch failure, suture disruption or bacterial endocarditis [

4]. Residual VSDs can cause congestive heart failure and result in elevated pulmonary vascular resistance [

5]. Residual VSDs, time from myocardial infarction to VSD diagnosis and time from VSD diagnosis to treatment have been identified as predictors for mortality [

3]. Significant shunts with a Qp: Qs of >1.5 are considered an indication for repeat surgery albeit associated with an even higher perioperative mortality rate. Transcatheter closure of a residual VSD has been performed with a variety of devices, among them Amplatzer muscular and perimembranous occluders. Dua et al. reported successful residual VSD closure in 22 patients of whom only three (14%) were found to have a small residual shunt on transthoracic echocardiography immediately after device deployment, which on follow-up had disappeared [

6]. They also concluded that there was no significant relationship between the outcome and location of the VSD.

This case report is noteworthy because this young man had sustained a cerebrovascular accident following a paradoxical embolism via a PFO seven years before his MI. An incidental coronary angiogram was considered because of his risk profile but discarded as he was only 35 years old at that time. Had the coronary angiogram been performed, it might have allowed a timely identification of clinically silent coronary artery disease and called in acetylsalicylic acid treatment beyond the brief treatment after PFO closure, a statin, and perhaps a revascularization or at least regular exercise tests. This could have possibly prevented or at least postponed the MI with subsequent VSD.

Wahl et al. had performed incidental coronary angiography in 575 patients (men > 40 and women > 50 years or younger patients with particular risk patterns) without overt history, signs or symptoms of coronary artery disease and found a rather high prevalence of diseased coronary arteries in 164 patients (29%) of which 53 (9%) had a significant disease defined as >50% diameter stenosis [

7]. This patient could have benefitted from such an approach.