Results

Structure of Swiss centres

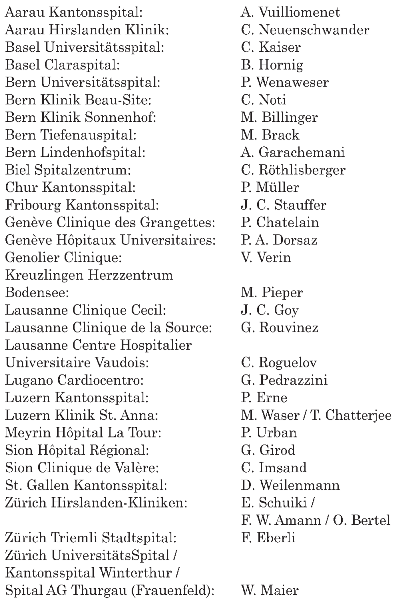

In 2008, there were 29 active centres (5 university, 10 public non-university, 14 private hospitals), all of which performed both diagnostic procedures and percutaneous cardiac interventions. Compared to 2007 there was one new centre in 2008, the Clinique de Valère in Sion. In 2009, the Hirslandenkliniken in Zürich (previously Klinik Im Park, Klinik Hirslanden Zürich) began to report their data as a single centre, which also included interventional activities in the Lindberg Clinic in Winterthur. In contrast to previous years, the Lindenhofspital in Bern also participated in the 2009 survey. Thus there were also 29 centres in 2009 (5 university, 10 public non-university, 14 private hospitals). As in previous years, the University Hospital Zürich (UniversitätsSpital Zürich; USZ), the Kantonsspital Winterthur (KSW) and Spital Thurgau AG (Frauenfeld, FF) were treated as a single centre. In 2008, 13 institutions had one catheterisation laboratory, 12 centres had two, three centres had three, and one centre (USZ/ KSW/FF) performed procedures in five locally separated catheterisation laboratories. In 2009, 14 centres had one laboratory, 11 centres had two, two centres had three, one centre (USZ/KSW/FF) had five locally separated laboratories, and one centre (Hirslandenkliniken Zürich) had six locally separated laboratories. In 2008, 47 (2007: 34) operators performed coronary angiographies (CA) only, whereas 143 (2007: 138) cardiologists performed both CA and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI). In 2009, 41 operators performed CA only and 141 operators performed both CA and PCI. In 18 centres cardiac surgery was available on site in 2008 and 2009.

Coronary interventions

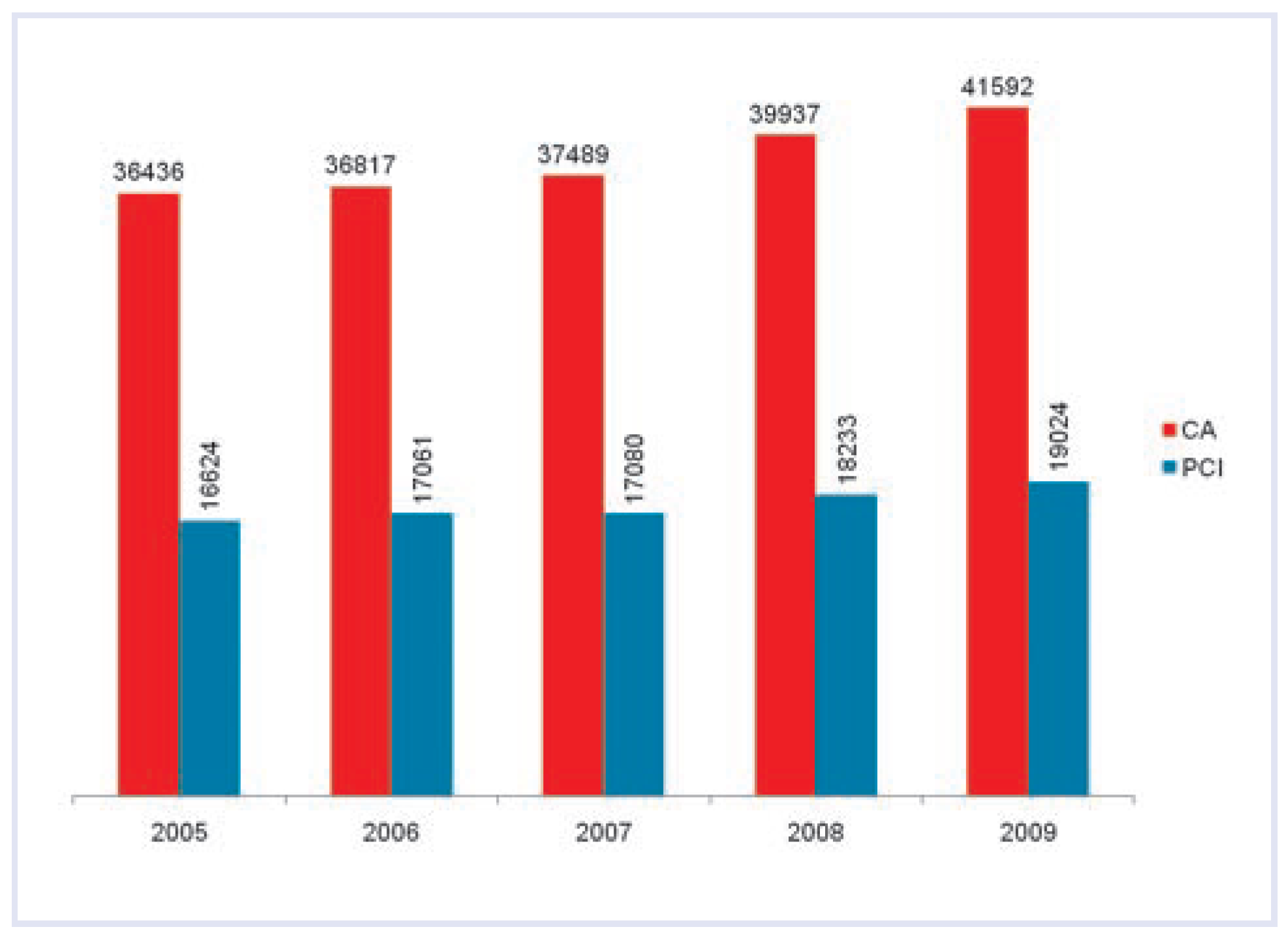

During 2008, 39 937 CA (2007: 37 489; +6.5%) and 18 233 PCI (2007: 17 080; +6.8%) were performed. In 2009, there was a further increase in CA (41 592; +4.1% compared to 2008) and PCI (19 024; +4.3% compared to 2008). Thus, in contrast to the observations between 2005 and 2007 there was an increase in the number of both CA and PCI (

Figure 1). The PCI/CA ratio remained unchanged at 45.7% between 2007 and 2009. PCI was performed

ad hoc in the majority of cases (2008: 91%; data not available from six centres; 2009: 89%; data not available from two centres). The majority of PCI procedures constituted single-vessel interventions (2008: 81%; data not available from four centres; 2009: 80%; data not available from one centre).

Figure 1.

Evolution of coronary angiographies (CA) and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) from 2005 to 2009.

Figure 1.

Evolution of coronary angiographies (CA) and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) from 2005 to 2009.

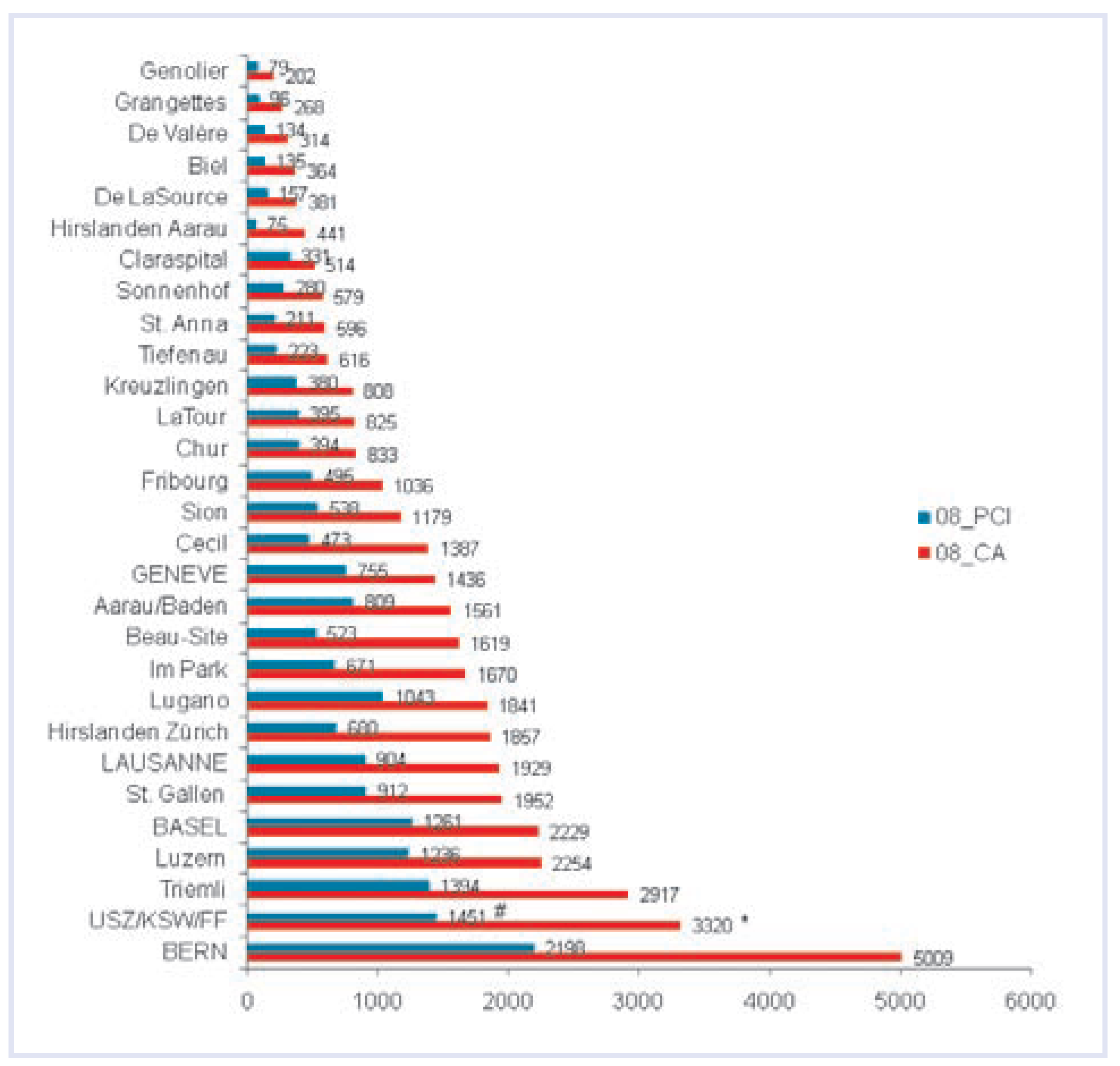

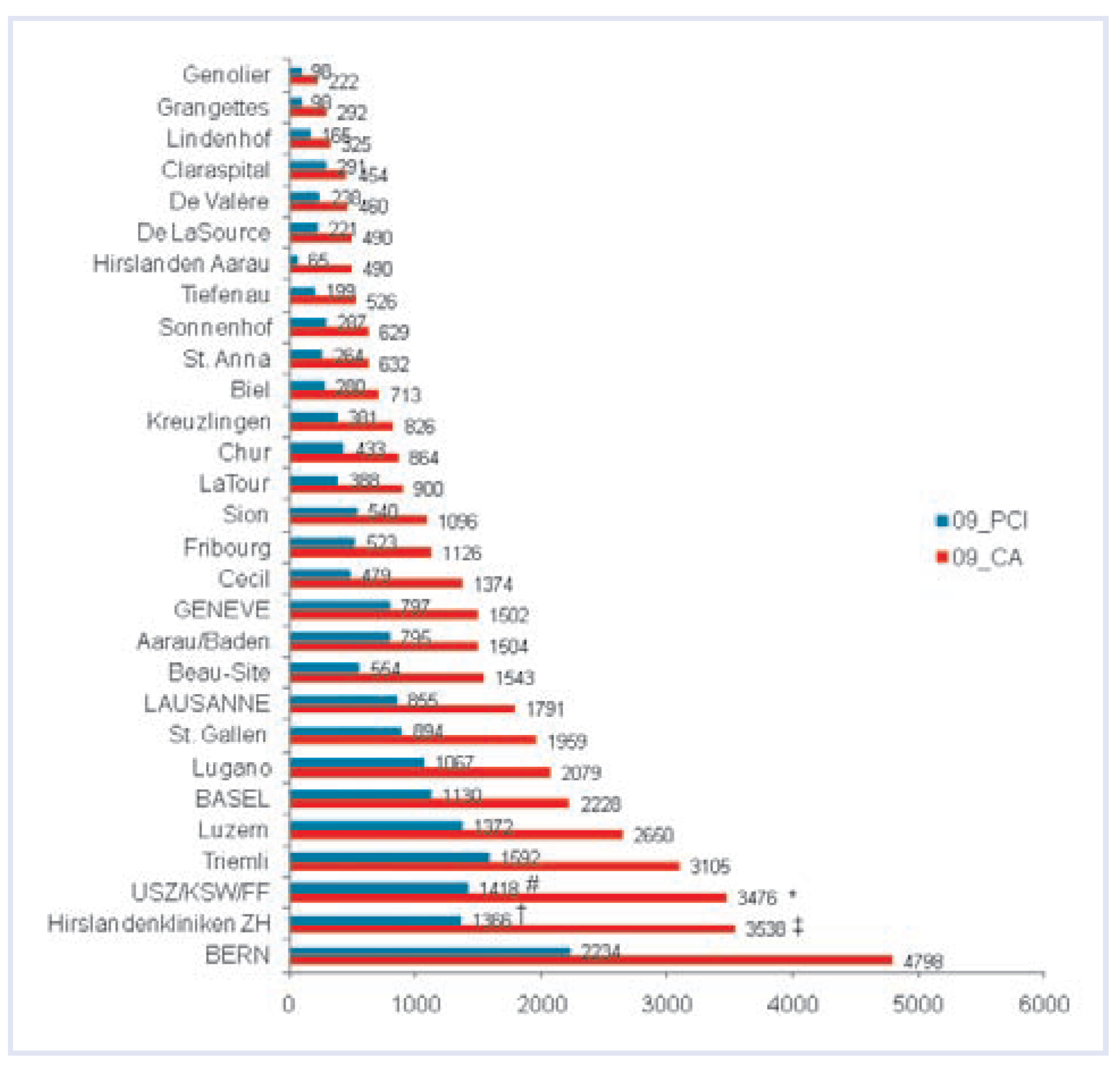

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show the distribution of CA and PCI among the different centres in 2008 and 2009, respectively. In 2008, the calculated average numbers of CA and PCI performed per operator were 210 (2007: 218) and 128 (2007: 124), respectively. The average number of PCI per operator was 164 (2007: 157) in university hospitals, 156 (2007: 154) in public non-university hospitals, and 79 (2007: 76) in private hospitals. In 2009, the average numbers of CA and PCI per operator were 230 and 136, respectively. The average number of PCI per operator was 184 in university hospitals, 164 in public non-university hospitals, and 84 in private hospitals.

Figure 2.

Coronary angiographies (CA) and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in different Swiss centres during the year 2008. The centres are grouped according to their annual CA volume. * USZ: 2649, KSW: 460, FF: 211; # USZ: 1197, KSW: 193, FF: 61. USZ = UniversitätsSpital Zürich; KSW = Kantonsspital Winterthur; FF = Spital AG Thurgau (Frauenfeld).

Figure 2.

Coronary angiographies (CA) and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in different Swiss centres during the year 2008. The centres are grouped according to their annual CA volume. * USZ: 2649, KSW: 460, FF: 211; # USZ: 1197, KSW: 193, FF: 61. USZ = UniversitätsSpital Zürich; KSW = Kantonsspital Winterthur; FF = Spital AG Thurgau (Frauenfeld).

Figure 3.

Coronary angiographies (CA) and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in different Swiss centres during the year 2009. The centres are grouped according to their annual CA volume. * USZ: 2797, KSW: 442, FF: 237; # USZ: 1125, KSW: 185, FF: 108; † Herzzentrum Hirslanden: 663, HerzGefässZentrum Klinik im Park: 676, Klinik Lindberg: 27; ‡ Herzzentrum Hirslanden: 1832, HerzGefässZentrum Klinik im Park: 1627, Klinik Lindberg: 79. USZ = UniversitätsSpital Zürich; KSW = Kantonsspital Winterthur; FF = Spital AG Thurgau (Frauenfeld).

Figure 3.

Coronary angiographies (CA) and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in different Swiss centres during the year 2009. The centres are grouped according to their annual CA volume. * USZ: 2797, KSW: 442, FF: 237; # USZ: 1125, KSW: 185, FF: 108; † Herzzentrum Hirslanden: 663, HerzGefässZentrum Klinik im Park: 676, Klinik Lindberg: 27; ‡ Herzzentrum Hirslanden: 1832, HerzGefässZentrum Klinik im Park: 1627, Klinik Lindberg: 79. USZ = UniversitätsSpital Zürich; KSW = Kantonsspital Winterthur; FF = Spital AG Thurgau (Frauenfeld).

Coronary stents

Stent utilisation rates in 2008 and 2009 were 92% (data not available from one centre) and 90% (data not available from one centre), respectively. In 2008, during 42% of PCI procedures (2007: 42%), two or more stents were implanted (data not available from four centres). In 2009, in 41% of PCI two or more stents were implanted (data not available from three centres). With 72% of all stents in 2008 (data not available from three centres) and also 72% in 2009 (data not available from one centre), DES constituted the most frequently used stent type. The use of DES since their introduction in Switzerland is shown in figure 4. The proportion of DES varied considerably among different centres, ranging from 17 to 93% in 2008 and from 30 to 96% in 2009.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the use of drug-eluting stents between 2002 and 2009. The bars represent the drug-eluting stent utilisation rates (percutaneous coronary interventions [PCI] with drug-eluting stent placement/ all PCI with stent implantation).

Figure 4.

Evolution of the use of drug-eluting stents between 2002 and 2009. The bars represent the drug-eluting stent utilisation rates (percutaneous coronary interventions [PCI] with drug-eluting stent placement/ all PCI with stent implantation).

PCI for acute myocardial infarction

Emergency interventions in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction ([STEMI]; primary PCI or rescue PCI after failed thrombolysis) accounted for 20% of PCI procedures in 2008 (data not available from five centres; 2007: 22%) and 18% in 2009 (data not available from two centres). In 2009, 26/29 (90%) centres reported PCI for STEMI. Percutaneous coronary intervention for cardiogenic shock accounted for 1.0% of PCI in 2008 (data not available from six centres) and 1.8% in 2009 (data not available from one centre). During 2008, 428 (2007: 435) intraaortic balloon pumps and 50 (2007: 66) percutaneous left ventricular assist devices were used. In 2009, 477 intraaortic balloon pumps and 47 percutaneous left ventricular assist devices were implanted. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors were used in 19% in 2008 (data not available from five centres; 2007: 24%) and 17% in 2009 (data not available from one centre).

Adjunctive techniques and special interventions

Distal protection devices were used in 1.3% of PCI cases in 2008 and 1.9% in 2009. An intracoronary pressure wire was employed in 3.2% of cases in 2008 and 4.2% in 2009. Intravascular ultrasound was performed in 3.7% of PCI in 2008 and in 5.0% in 2009. Revascularisation techniques other than balloon angioplasty included rotablation (2008: 77 cases; 2009: 76 cases) and atherectomy (2008: 0 cases; 2009: 28 cases). Alcohol ablation of septal hypertrophy was performed in 11 patients in 2008 and 38 patients in 2009 (2007: 31).

Management of puncture site

The femoral artery was the most commonly used access site in 2008 (87%; data not available from four centres) and 2009 (85%; data not available from two centres). Approaches other than the femoral artery seemed to be more popular in French-speaking Switzerland (2008: 23% non-femoral approaches, 2009: 32% non-femoral approaches) than in the Germanspeaking part and Ticino (2008: 2% non-femoral approach, 2009: 6% non-femoral approaches). Closure devices were frequently used (2008: 39% manual compression; data not available from six centres; 2009: 38% manual compression; data not available from three centres).

Non-coronary interventions

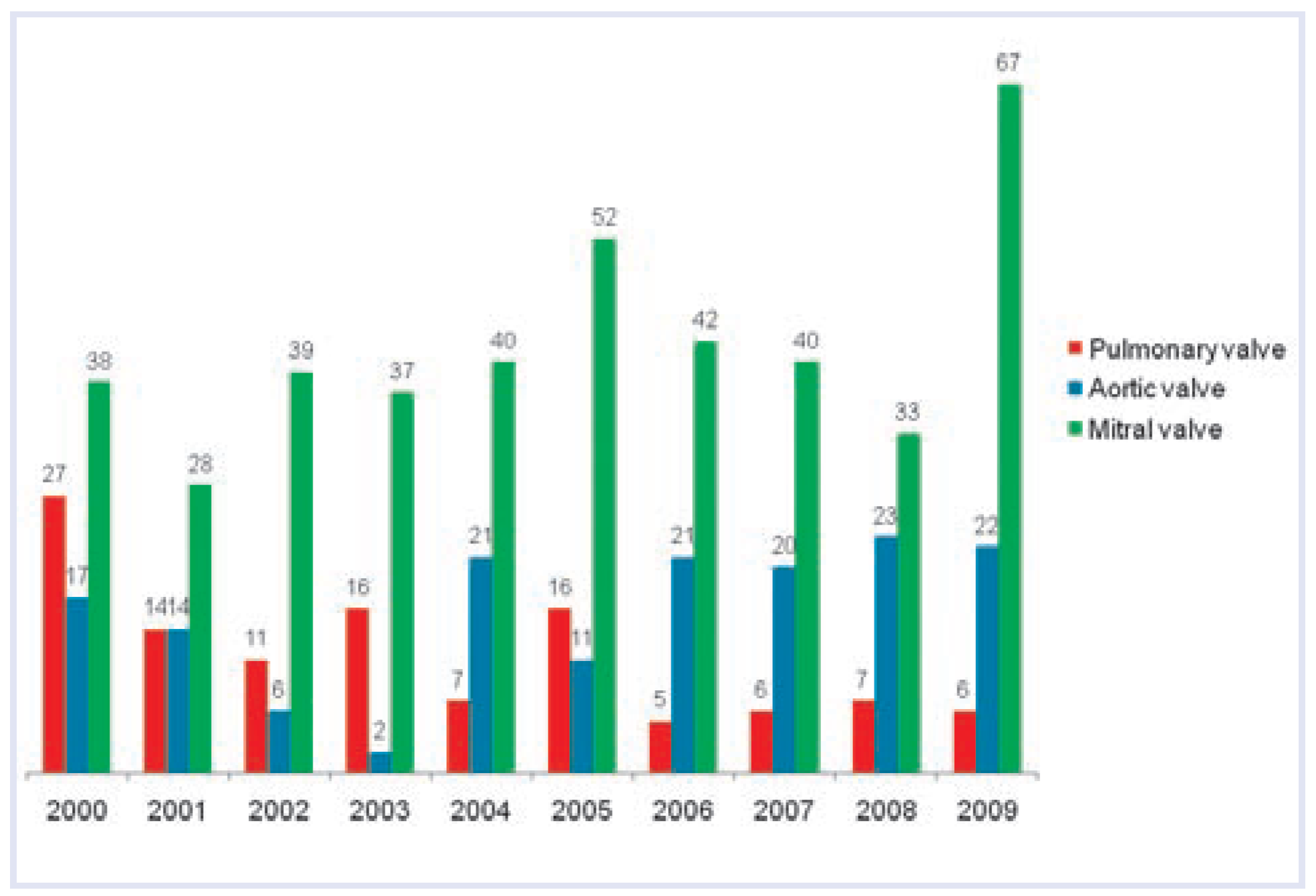

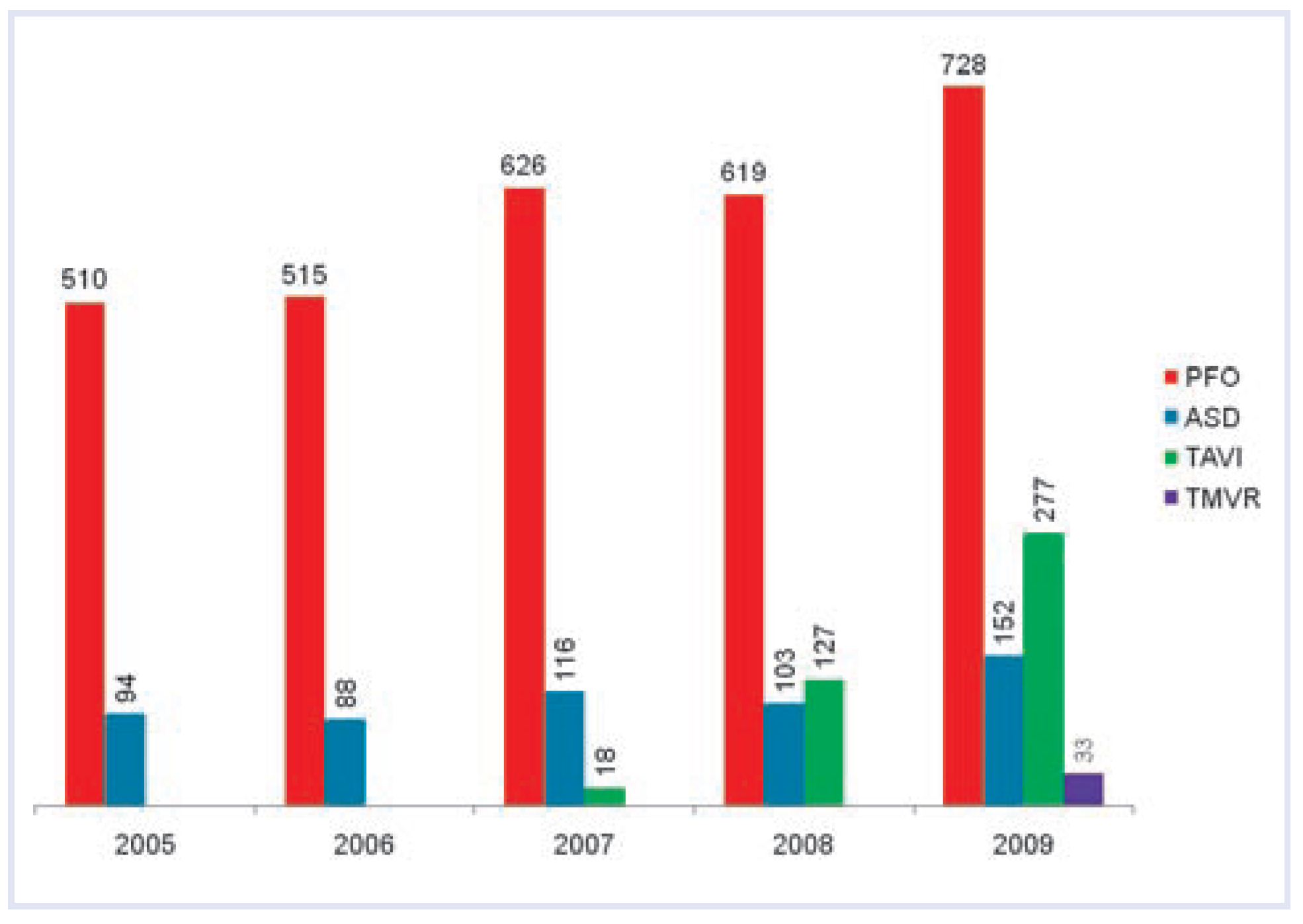

While the number of balloon valvuloplasties for the aortic and pulmonary valve did not markedly differ from previous years, there were a larger number of mitral valvuloplasties in 2009 (

Figure 5). Apart from standard valvuloplasties there was a rapidly growing number of novel interventions for valve disease. In the first two years after its introduction in Switzerland there was a marked increase in TAVI procedures (

Figure 6). While TAVI was performed in only one centre in 2007, seven centres (four university hospitals, two public non-university hospitals and one private hospital) offered TAVI in 2008, and eight centres (five university hospitals, two public non-university hospitals, and one private) offered TAVI in 2009. In 2009, the majority of valves were transfemoral implants (n = 206), but there were also a considerable number of transapical procedures (n = 71). In addition, transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVR) was introduced (a total of 33 cases performed in one university hospital, one public non-university centre, and one private hospital).

Figure 5.

Balloon valvuloplasties from 2000 to 2009. The figure does not include transcatheter aortic valve implantation and transcatheter mitral valve repair procedures.

Figure 5.

Balloon valvuloplasties from 2000 to 2009. The figure does not include transcatheter aortic valve implantation and transcatheter mitral valve repair procedures.

Figure 6.

Interventions for structural heart defects: closure of atrial septal defect (ASD) and patent foramen ovale (PFO), transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVR) from 2005 to 2009.

Figure 6.

Interventions for structural heart defects: closure of atrial septal defect (ASD) and patent foramen ovale (PFO), transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVR) from 2005 to 2009.

The numbers of procedures for patent foramen ovale (PFO) and atrial septal defect (ASD) closure remained more or less unchanged in 2008. However, there was a further increase in the number of these procedures in 2009, and there has been a clearcut net increase over the last five years (

Figure 6).

Discussion

The 2008/2009 survey on the practice of interventional cardiology in Switzerland revealed three main findings: First, after the numbers of CA and PCI had reached a plateau over the previous few years, there was a substantial increase in the numbers of both CA and PCI in 2008 and 2009, with an unchanged PCI/CA ratio. Second, the proportion of DES remained unchanged following the decrease in 2006, and represents nearly three quarters of all stent-based PCI. Third, TAVI has been rapidly adopted in Switzerland.

The reason for the increase in the number of CA is unclear but several explanations are plausible. First, non-invasive methods to identify inducible myocardial ischaemia other than the simple exercise stress test (i.e., myocardial perfusion SPECT, stress echocardiography and perfusion cardiac magnetic resonance imaging) are apparently on the increase. These relatively sensitive tests may have resulted in more CA indications. In addition, the numbers of computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA) have significantly increased in Switzerland in recent years (e.g., published data from two university hospitals [

3,

4,

5]. It may be speculated that positive CTCA findings have created more indications for CA/PCI too, to confirm and treat significant coronary artery disease. On the other hand, CTCA is known to produce false positive findings, which may also have resulted in additional indications for CA to refute findings from CTCA. It has also been realised that the largest study comparing PCI with current medical treatment, the COURAGE study [

6], allows only limited conclusions concerning optimal management in real-life patients because an initial CA was required in all patients even if a medical rather than an invasive therapeutic approach was adopted, and the population finally included in the trial was highly selected (6.4% of all patients screened) and had relatively few symptoms [

7]. Thus, COURAGE is unlikely to have significantly affected patient selection for CA.

The very stable PCI/CA ratio indicates that the practice of proceeding to PCI after CA was not significantly affected by the COURAGE trial [

6] and other studies comparing optimal medical treatment with PCI. First, it is undisputed that PCI is highly effective in alleviating symptoms of angina pectoris. Second, the relevance of COURAGE has been questioned not only because of the selected populations studied but also because the follow-up time may have been too short [

8]. In fact, a Swiss study with a 10-year follow-up documented fewer cardiac events in patients with recent myocardial infarction, documented silent ischaemia, and single or double-vessel disease undergoing PCI aimed at full revascularisation compared to those treated with intense anti-ischaemic drug therapy [

9].

The current PCI/CA ratio of 46% in Switzerland is significantly higher than in Austria (39%) [

10] and Germany (36%) [

11]. A recent analysis of CA data collected between 2004 and 2008 in the United States revealed that only 38% of patients undergoing elective CA had significant coronary artery disease [

12]. Thus, indications for CA are unlikely to be more liberal in Switzerland than in other countries with a similar infrastructure. The increase in CA with an unchanged PCI/CA ratio also points to the fact that the larger number of CA is not simply the result of additional examinations based on soft indications, but may reflect the underuse of revascularisation and the expansion of non-invasive testing as discussed above.

The increasing number of CA and PCI may not only reflect the preference for an invasive strategy by patients and physicians, but also raises questions about the prevalence of significant CAD in Switzerland. Repeat CA and PCI in patients surviving an infarct who would not have done so in the pre-acute PCI era, but also more patients presenting with de novo symptoms, may account for the increasing number of procedures. Unfortunately, primary prevention is still not optimal in all respects in Switzerland, particularly with regard to lipid [

13] and weight [

14] management, which may be a reason why CA and PCI are not decreasing.

Similarly to previous years, stent implantation was performed during the vast majority of PCI in 2008 and 2009. After a slight decrease in the proportion of DES from 2006 to 2007 [

2], DES utilisation remained stable in 2008 and 2009. This approach is justified by evidence showing that DES use is associated with a 50– 70% reduction in the risk of repeat revascularisation compared with bare metal stents, whereas the risk of death or myocardial infarction was similar [

15]. Moreover, newer generations DES have been shown to further decrease ischaemic and revascularisation events [

16,

17] compared with early generation DES. Thus, given the benefit of DES in terms of reduced target lesion revascularisation, and the similar or superior outcome in terms of ischaemic adverse events [

15], the proportion of DES is likely to expand.

A substantial number of CA and PCI are performed by a non-femoral, i.e., radial approach. The radial artery is easier to compress, and the radial approach has been shown to be associated with fewer bleeding complications and allows earlier ambulation. The drawbacks include the risk of spasm and thrombosis, and the cross-over rate to the femoral approach is higher than the opposite way [

18]. Interestingly, the radial approach is much more popular in the French-speaking part of Switzerland.

There is a clear trend towards more transcatheter procedures for structural heart disease. After its introduction in Switzerland in 2007, the use of TAVI has expanded rapidly in the country. Removal of outflow obstruction is the only therapy to improve survival in patients with aortic stenosis. The adoption of transcatheter aortic implantation reflects an unmet need of patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis deemed at increased risk of conventional surgical aortic valve replacement, as evidenced by up to one third of such patients not being referred for this life-saving therapy. Favourable procedural results and medium-term clinical outcomes for TAVI in high-risk patients have been reported, including octogenarians, patients with previous cardiac surgery, frail patients, those with porcelain aorta [

19,

20] and valve-in-valve therapy for failed bioprostheses. It has been suggested that indications for TAVI may widen in the future to take in patients at lower risk [

8]. A trial comparing surgical valve replacement and TAVI in high-risk patients is under way (the placement of aortic transcatheter valves [PARTNER] trial [

21]). Notably, TAVI is still not reimbursed in Switzerland, in contrast to other European countries including France and Germany.

Apart from TAVI, options for transcatheter treatment of mitral regurgitation [

22,

23] have become available in Switzerland. Three centres offered TMVR in 2009, and developments in the field of interventions in valvular heart disease will be of particular interest in the coming years.

The number of procedures for PFO and ASD has risen substantially during the last five years. While treatment of a haemodynamically relevant shunt due to an ASD may have accounted for a small minority of these procedures, it can be assumed that the majority of procedures were performed as secondary prevention after cryptogenic stroke. Indications for PFO closure are still debated. It is widely accepted that young patients with recurrence of stroke despite antithrombotic therapy should undergo PFO closure. The association between PFO with and without atrial septal aneurysm and stroke was initially accepted only for younger patients (<55 years). A large observational study published in 2007 suggests that such a relationship may also apply for older patients [

24] and may have contributed to the ongoing rise in the number of procedures for PFO closure. Results of ongoing prospective randomised trials comparing PFO closure with medical therapy, such as the PC trial, are awaited and will better define the role of PFO closure in stroke patients [

25].