Introduction

The clinical outcome of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) has dramatically improved since the introduction of fibrinolysis and primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Although fibrinolysis is still the most common method of reperfusion worldwide, rapid transfer to a cardiac catheterisation laboratory with primary PCI has evolved as the preferred reperfusion therapy in Switzerland. Well-balanced antithrombotic therapy is especially important for a successful and stable recanalisation of the thrombotic coronary occlusion site without an increase in severe bleeding complications.

International consensus guidelines on antithrombotic treatment in the STEMI setting are updated on a regular basis [

1,

2], and provide rather general than practical recommendations for the various antithrombotic treatment regimens. The authors have reviewed the available evidence of antithrombin treatment regimens during an expert consensus conference (see acknowledgement). In accordance with a recently published article on the antithrombotic management of patients with Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction [

3], this article provides practical dose schemes of various antithrombic treatment strategies in STEMI patients with special attention to the primary management strategy: primary PCI, fibrinolysis or conservative management without reperfusion.

Unfractionated heparin

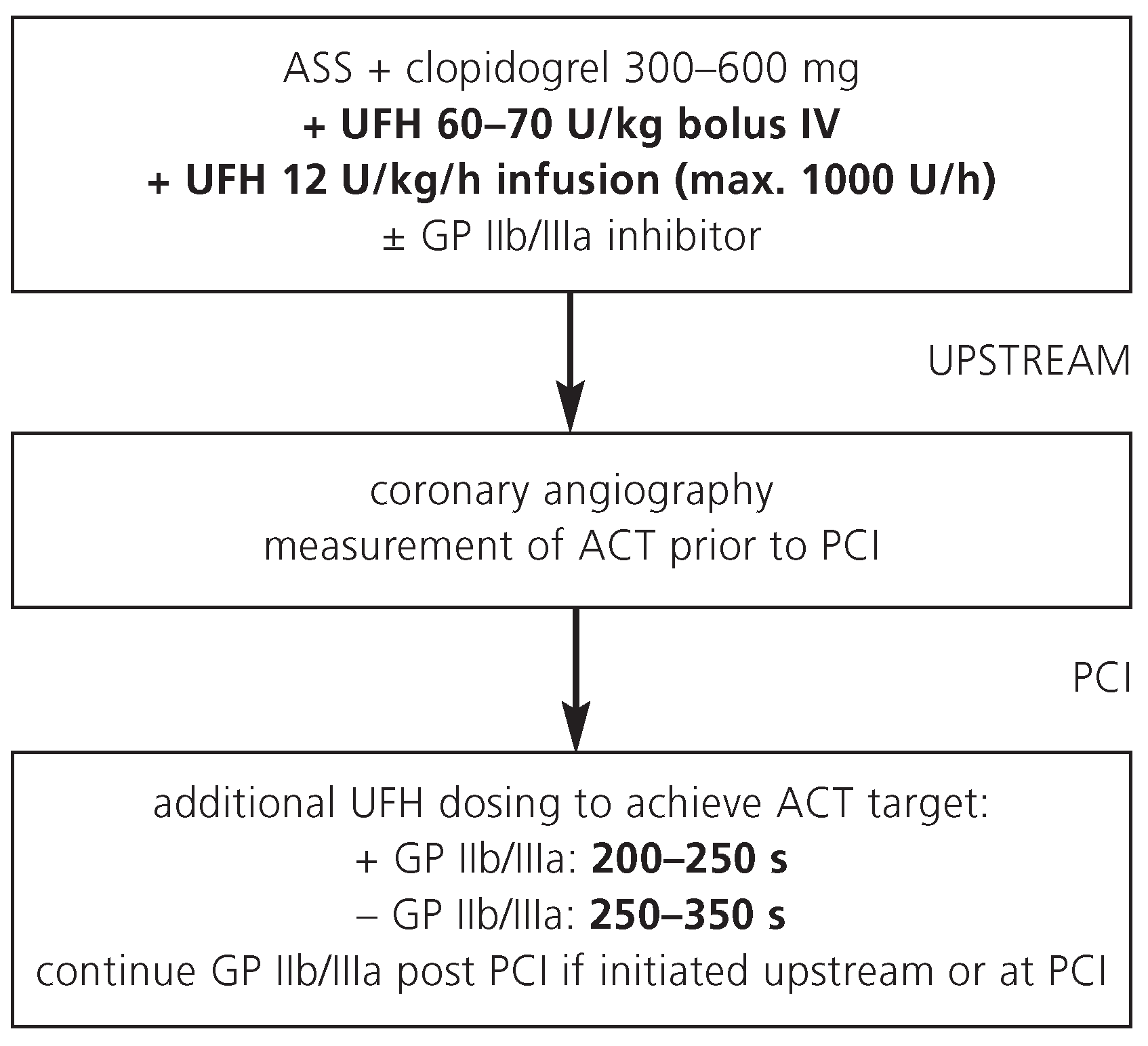

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) is the most commonly used antithrombin agent in STEMI patients referred for primary PCI. Advantages of UFH include its long history of use, low cost, and rapid reversibility by protamin in case of bleeding complications. UFH is immunogenic by binding to platelet factor 4 with the risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Because of its inconsistent effect in individual patients, UFH requires close anticoagulant monitoring. UFH is administered upstream prior to coronary angiography as intravenous bolus and a continuous infusion (

Figure 1). In most patients, additional UFH is administered during primary PCI according to the activated clotting time (ACT) obtained during coronary angiography.

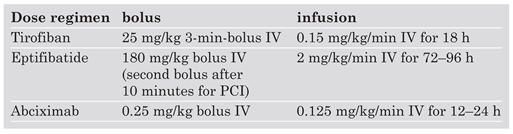

Primary PCI with UFH usually requires combination with GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Dose regimens for the GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors tirofiban, eptifibatide and abciximab are given on the

Table 1. Note that tirofiban requires dose-halving with a creatinin clearance of less than 30 ml per minute, while abciximab does not need dose adjustment with renal insufficiency.

Fibrinolysis or conservative management

In STEMI patients, thrombin activity is enhanced and plays a key role in promoting thrombus formation. Paradoxically, fibrinolysis further worsens the prothrombotic state and platelet activation by releasing a pool of trapped thrombin during the course of clot lysis [

4]. Although UFH impedes thrombin activity associated with thrombolysis, it does not inhibit thrombin generation, which in turn predicts subsequent thrombotic events [

5]. Both, enoxaparin and fondaparinux inhibit the coagulation cascade earlier and may therefore prove more effective than UFH in STEMI patients managed with fibrinolysis.

According to current international consensus guidelines [

1,

2], UFH may still be used for patients not undergoing primary PCI. However, it is now recommended to administer UFH no longer than 48 hours due to he risk of heparininduced thrombocytopenia [

1,

2,

6]

Bivalirudin

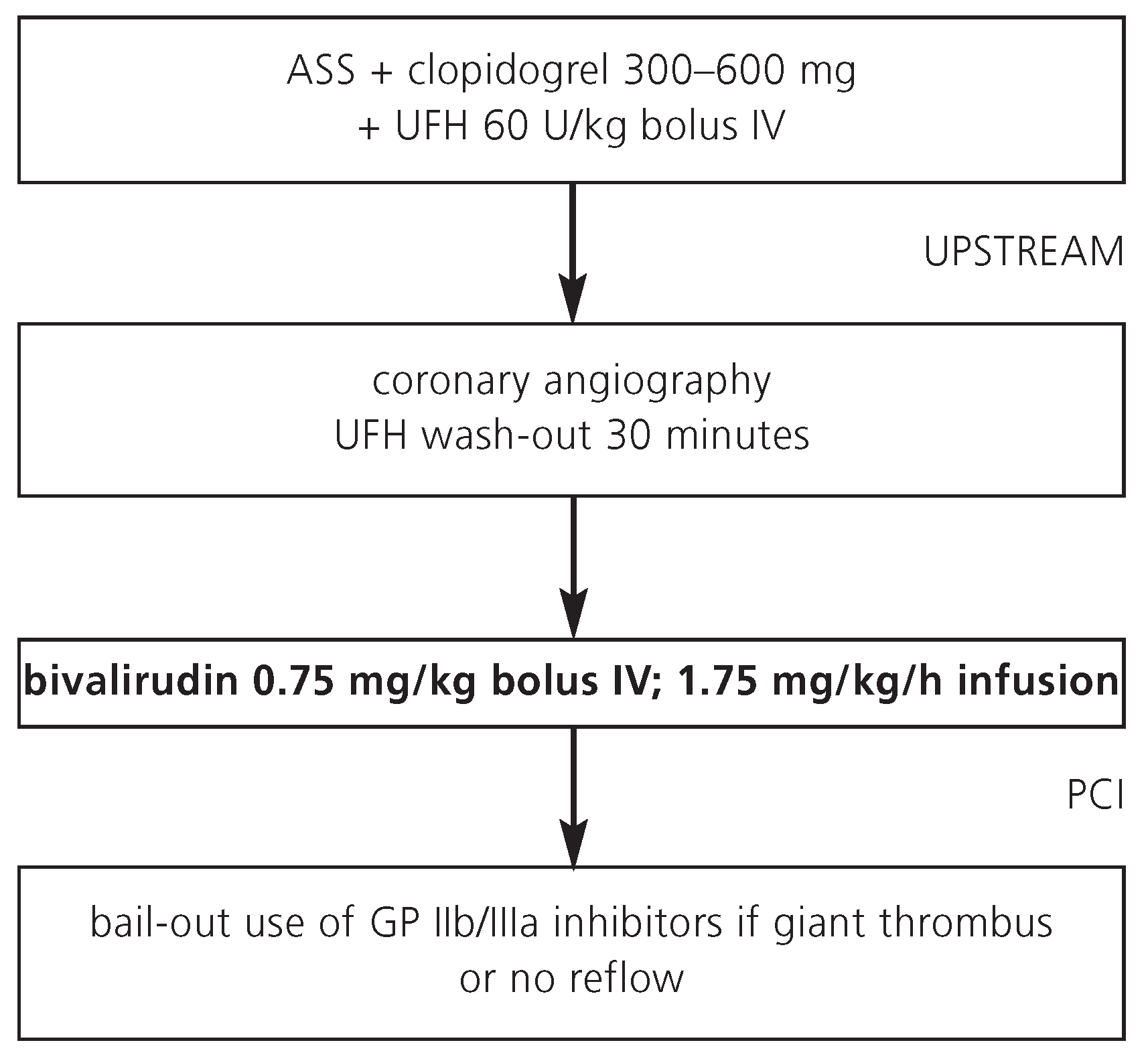

In STEMI patients managed with primary PCI, a bivalirudin alone strategy appears as effective as but safer than a strategy with UFH plus GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors. The risk of severe bleeding complications is lower with bivalirudin as compared with UFH plus GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors [

7]. Most STEMI patients receive UFH as initial antithrombin at presentation prior to referral to the catheterisation laboratory (

Figure 2). If a bivalirudin strategy is chosen, no UFH infusion is required during a rapid transport to the catheterisation laboratory. Of note, bivalirudin can be combined with GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors in case of giant thrombus, distal embolisation, or no reflow (bail-out indication), without an increase in major bleeding complications [

7,

8]. Because of the small risk of acute stent thrombosis <24 hours with a bivalirudin alone strategy, it appears useful to initiate clopidogrel pre-treatment (preferably 600 mg) already at presentation. Due to the short half-life of 25 minutes, it appears also useful to continue the bivalirudin infusion after conclusion of the PCI procedure until the complete amount of the bivalirudin vial (250 mg) has been used.

Fibrinolysis or conservative management

Currently, bivalirudin has no role for STEMI patients managed conservatively or with fibrinolysis.

Enoxaparin

In the absence of large randomised controlled trials, enoxaparin has not been recommended for patients managed with primary PCI.

Fibrinolysis or conservative management

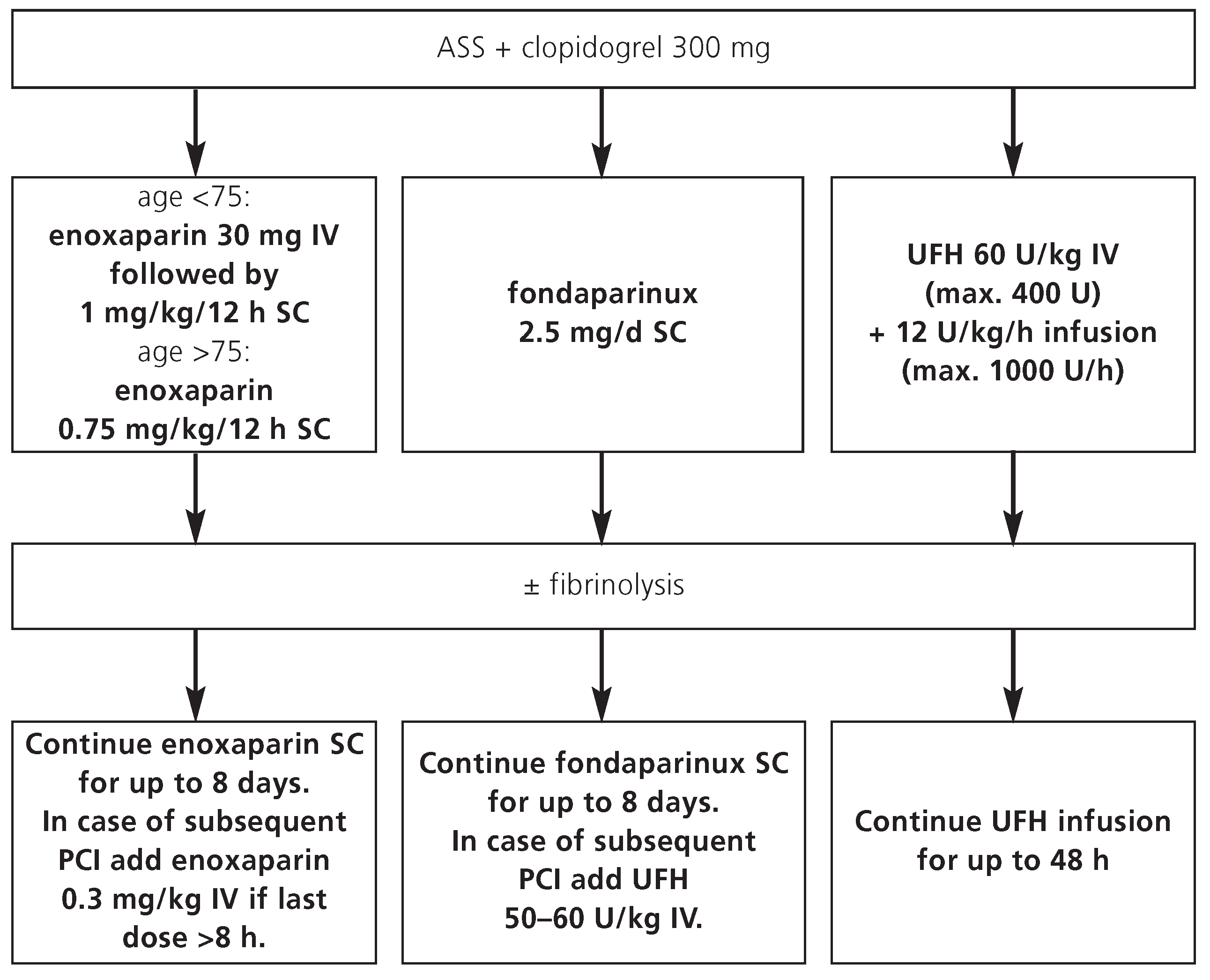

In a systematic review of available data, enoxaparin is more effective than UFH with a higher risk of major bleeding complications in STEMI patients who are managed with fibrinolysis [

9,

10]. Overall, the benefit/risk ratio defined as death, recurrent myocardial infarction and major bleeding is in favour of enoxaparin [

11,

12]. Enoxaparin is recommended for up to 8 days or until discharge (whatever comes first) in STEMI patients managed conservatively or with fibrinolysis. In case of subsequent PCI during the index hospitalisation, intravenous enoxaparin can be used during the intervention, depending on the time of the last subcutaneous injection (

Figure 3). Due to the lack of data, other low-molecular weight heparins than enoxaparin are not recommended for this indication.

Fondaparinux

Fondaparinux is not recommended in STEMI patients managed with primary PCI due to increased risk of cardiovascular events in comparison to treatment with UFH.

Fibrinolysis or conservative management

Similar to enoxaparin, fondaparinux is recommended in patients with STEMI, who are managed conservatively or with fibrinolysis, for up to 8 days or until discharge (whatever comes first) (

Figure 3).

In case of subsequent PCI during the index hospitalisation, fondaparinux cannot be used as sole antithrombin agent during PCI due to an increased rate of guiding catheter thrombosis [

13,

14]. Therefore, intravenous UFH is required during PCI of STEMI patients who received fondaparinux upstream to avoid this rare but potentially fatal complication, although more data are required to confirm the efficacy and safety of such a strategy [

15].

Conclusions

For STEMI patients managed with primary PCI, UFH in combination with GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors currently remains the most often used antithrombotic treatment regimen. In elderly STEMI patients or those with an increased bleeding risk, a bivalirudin alone strategy is becoming an increasingly popular antithrombin strategy for primary PCI due to a marked reduction in bleeding complications without significant increase in thrombotic events.

For STEMI patients managed conservatively or with fibrinolysis, UFH is no longer standard treatment. For this indication, extended-duration enoxaparin or fondaparinux for up to 8 days have emerged as preferred antithrombin treatment options. In case of subsequent PCI, additional intravenous enoxaparin can be use during the intervention, whereas periprocedural UFH is required in patients who have received upstream fondaparinux.

Acknowlegement

The authors thank Dr David Spirk from Sanofi-Aventis (Suisse) SA, for organising and sponsoring the Expert Consensus Meeting on antithrombotic treatment in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction, held on March 11, 2007 in Berne, Switzerland.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Kucher received a honorarium from Sanofi-Aventis for participating at the Expert Consensus Meeting on antithrombotic treatment in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction, held on March 11th, 2007, in Berne, Switzerland.

References

- Antman, E.M.; Hand, M.; Armstrong, P.W.; et al. 2007 Focused Update of the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2008, 117, 296–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, S.B.; Smith, S.C.; Hirshfeld, J.W.; et al. 2007 Focused update of the ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous Coronary Intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2008, 117, 261–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucher, N.; Windecker, S.; Mach, F.; et al. Antithrombin treatment of patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Kardiovaskuläre Medizin. 2008, 11, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Merlini, P.A.; Repetto, A.; Andreoli, A.M.; et al. Effect of abciximab on prothrombin activation and thrombin generation in patients with acute myocardial infarction also receiving reteplase. Am J Cardiol. 2004, 3, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semeraro, F.; Piro, D.; Rossiello, M.R.; et al. Profibrinolytic activity of the direct thrombin inhibitor melagatran and unfractionated heparin in platelet-poor and platelet-rich clots. Thromb Haemost. 2007, 98, 1208–1214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Joost, A.; Kurowski, V.; Radke, P.W. Anticoagulation in patients with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia undergoing percutaneous coronary angiography and interventions. Curr Pharm Des. 2008, 14, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, G.W.; Witzenbichler, B.; Guagliumi, G.; et al. Bivalirudin during primary PCI in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2008, 358, 2218–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, G.W.; McLaurin, B.T.; Cox, D.A.; et al. Bivalirudin for patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355, 2203–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, S.A.; Gibson, C.M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of the lowmolecular weight heparin enoxaparin compared with unfractionated heparin across the acute coronary syndrome spectrum: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2007, 28, 2077–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuseppe De Luca, M.D.; Marino, P. Adjunctive benefits from low-molecular-weight heparins as compared to unfractionated heparin among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with thrombolysis. A meta-analysis of the randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2007, 154, 1085.e1–1085.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antman, E.M.; Morrow, D.A.; McCabe, C.H.; et al. Enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin with fibrinolysis for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1477. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Morrow, D.A.; Dalby, A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction also treated with clopidogrel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007, 49, 2256–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yusuf, S.; Mehta, S.R.; Chrolavicius, S.; et al. Comparison of fondaparinux and enoxaparin in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2006, 354, 1464–1476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yusuf, S.; Mehta, S.R.; Chrolavicius, S., et. al. Effects of fondaparinux on mortality and reinfarction in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the OASIS-6 randomized trial. JAMA. 2006, 295, 1519–1530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mehta, S.R.; Granger, C.B.; Eikelboom, J.W.; et al. Efficacy and safety of fondaparinux versus enoxaparin in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the OASIS-5 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007, 50, 1742–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2008 by the author. Attribution Non-Commercial NoDerivatives 4.0.