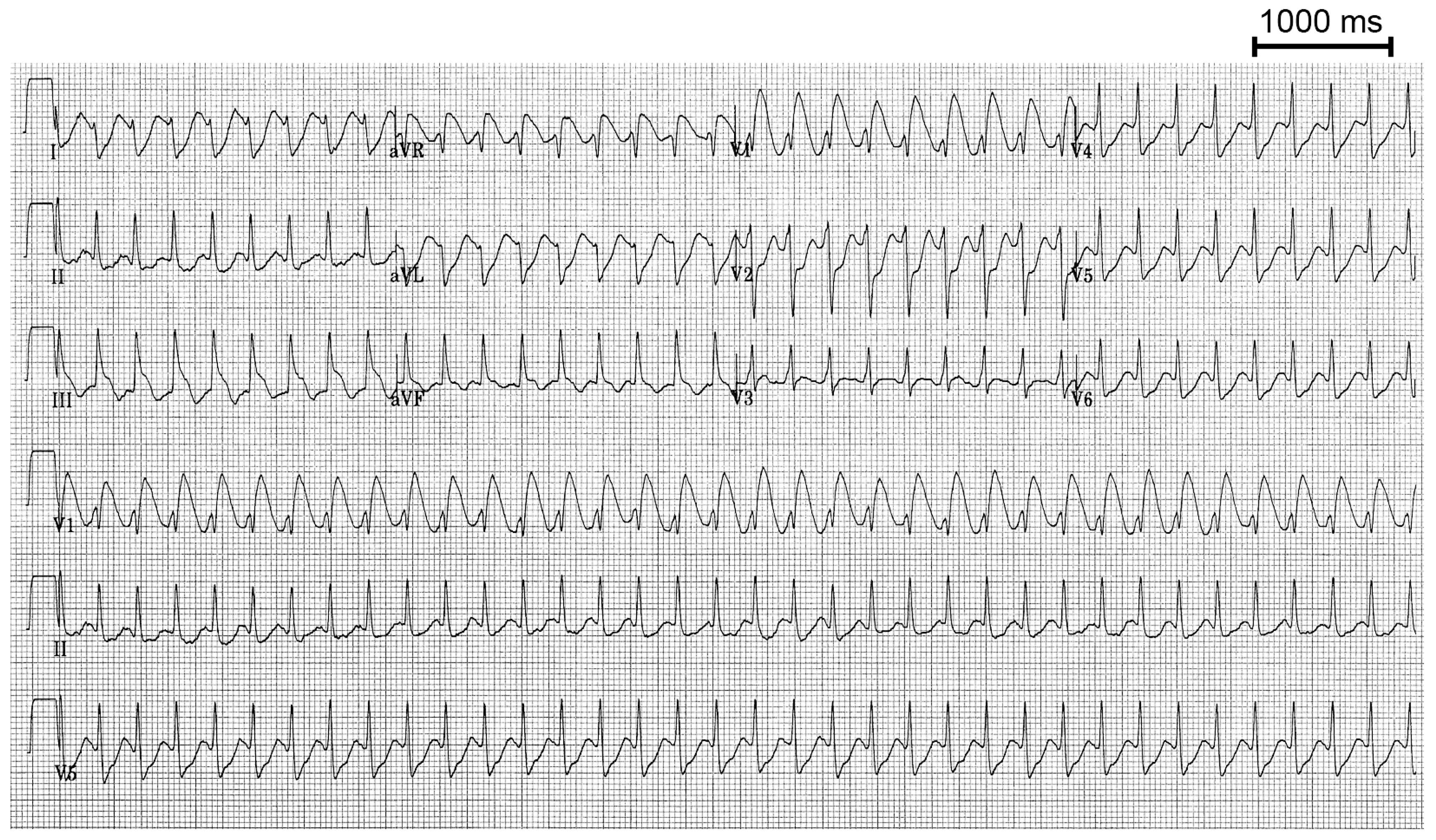

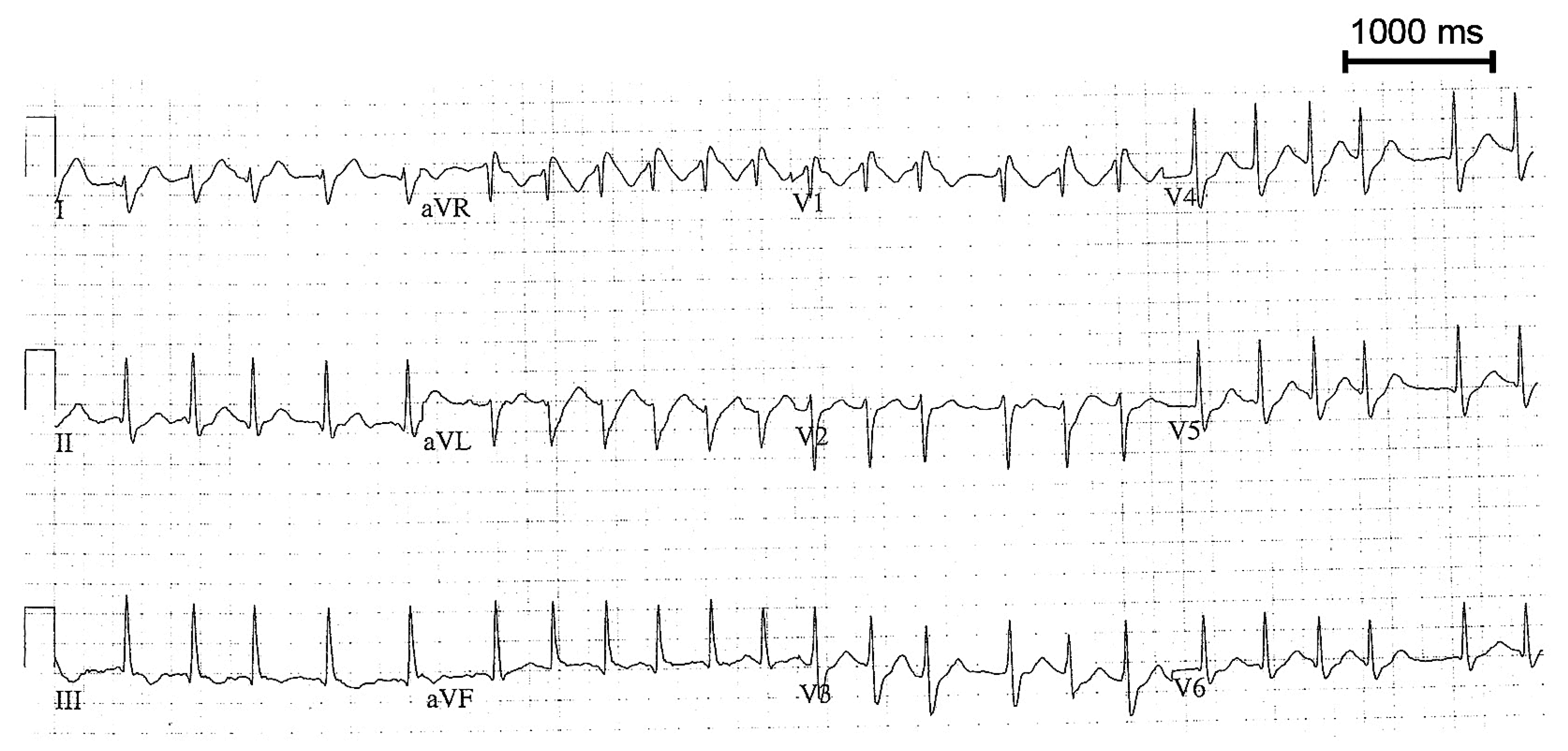

Regular Wide QRS Tachycardia Complicating Treatment for Atrial Fibrillation

Case presentation

Discussion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blomstrom-Lundqvist, C.; Scheinman, M.M.; Aliot, E.M.; Alpert, J.S.; Calkins, H.; Camm, A.J.; et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias – executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology committee for practice guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias). Circulation. 2003, 108, 1871–1909. [Google Scholar]

- Feld, G.K.; Chen, P.S.; Nicod, P.; Fleck, R.P.; Meyer, D. Possible atrial proarrhythmic effects of class 1C antiarrhythmic drugs. Am J Cardiol. 1990, 66, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, V.; Ryden, L.E.; Cannom, D.S.; Crijns, H.J.; Curtis, A.B.; Ellenbogen, K.A.; et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology committee for practice guidelines (writing committee to revise the 2001 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation): developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006, 114, e257–354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2008 by the authors. Attribution - Non-Commercial - NoDerivatives 4.0.

Share and Cite

Seiler, J.; Lee, J.C.; Roberts-Thomson, K.C. Regular Wide QRS Tachycardia Complicating Treatment for Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiovasc. Med. 2008, 11, 166. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2008.01328

Seiler J, Lee JC, Roberts-Thomson KC. Regular Wide QRS Tachycardia Complicating Treatment for Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiovascular Medicine. 2008; 11(5):166. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2008.01328

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeiler, Jens, Joseph C. Lee, and Kurt C. Roberts-Thomson. 2008. "Regular Wide QRS Tachycardia Complicating Treatment for Atrial Fibrillation" Cardiovascular Medicine 11, no. 5: 166. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2008.01328

APA StyleSeiler, J., Lee, J. C., & Roberts-Thomson, K. C. (2008). Regular Wide QRS Tachycardia Complicating Treatment for Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiovascular Medicine, 11(5), 166. https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2008.01328