“It’s All We Got Left”. Why Poor Smokers are Less Sensitive to Cigarette Price Increases

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material & Methods

2.1. Analysis of the Social Differentiation of Smoking, 2000–2008

2.2. Quantitative Analysis of Smoking Motives: Poor Smokers versus Other Smokers

2.3. Qualitative Analysis of Poor Smokers’ Motives

3. Results

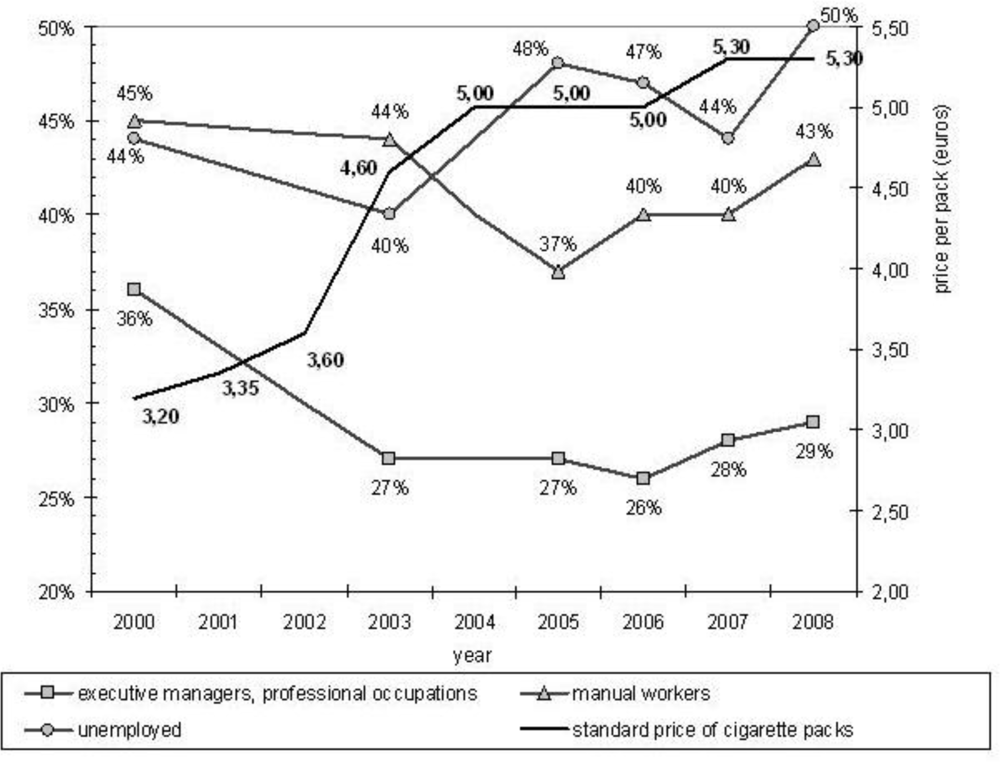

3.1. The Social Differentiation of Smoking in France, 2000–2008

3.2. Comparing Poor Smokers and Other Smokers’ Habits and Motives

3.3. Smoking Motives amongst the Poor: a Qualitative Exploration

I need a cigarette every five minutes or I lose my temper. (…) I would rather give up coffee, drinking and so on, but no, not smoking. It’s my drug. That’s all. (…) I feel it’s the only thing that keeps me going, the only thing. It’s the only company I have. (...) Even if the pack costs 50 €, I will buy it. But I don’t have so much money. I will never, never quit. (Philippe, man aged 50, homeless and unemployed)I am unbearable when I feel the urge for a cigarette. (…) I feel as if I’m going round in circles. I yell at everyone, my daughter doesn’t even talk to me because she knows I will send her packing. I’m just insufferable. Then I go downstairs in the street to find a cigarette. I ask people. (…) That’s the only thing I can beg for. It would never occur to me to beg for money. But a cigarette, sure, no problem. (Melina, woman aged 54, unemployed)When I feel the urge for a cigarette I could smoke butts picked up in the street. I could live without everything but the cigarettes. (…) I have been smoking for a long, long time. I’m so hooked to cigarettes. But I would like to quit right now. If only I could quit I would shout it out loud, yeah I would sing it “I quitted! I quitted” (…) When I need a fag I get extremely nervous, I search everywhere because sometimes I stash some cigarettes in the kitchen or in the living room, just in case. (…) When I inhale smoke it’s a little moment of happiness, something I steal just for me. (Manon, woman aged 56, clerk)

What worries me too is not being able to afford to give my wife and daughter a better life, a different life where they wouldn’t need to smoke like I do. I feel guilty about that. I would like to give them a life with less stress and worry, because – well, I get the minimum wage and we can’t make ends meet. I don’t earn much and we have to struggle. (…) My wife can’t give up smoking because of the stress. Poverty and living from day to day gives you nervous tension all the time, which creates a need. Cigarettes meet that need, although they are rather a poor substitute. They give one a little enjoyment. Since people can’t afford anything else, they rely on things like smoking. (Didier, man aged 53, manual worker)

I’m so intoxicated. (…) Okay, smoking gives cancer, but it also gives happiness, not a great happiness, but a little bit of it (…) I need my cigarettes because I don’t have spare-time activities, I’m broke, I don’t get out, I don’t go to the movies (…) There’s nothing here, we are miles from everywhere and there’s nothing to do. This place is dead and so are we. We should use our energy on other things than smoking and all that shit. (...) What do you think there is to do here? Going down to the pub? Meeting the same people, repeating the same bullshit, smoking cigarette after cigarette? (…) We’re like zombies here because we’re miles from everywhere. Look, a swimming pool, it would be great to have a pool nearby... If there was a pool, I would go swimming every day. Instead of smoking, I would go swimming, for example. It may sound stupid, but it’s not that stupid, actually (...) I haven’t got a car, and I couldn’t afford the petrol anyway (...) I’m not going to hitch a lift to the swimming pool, am I? (Camille, woman aged 60, retired)Smoking, yes it costs me more than 100 € a month... That’s a lot. It makes the budget rather tight, but thanks to my partner’s job, we practically manage to get to the end of the month – some months a least. Anyhow, cigarettes are a definite item, there’s no arguing about that. (…) I would like to stop smoking – um, because of the dough – to do other things with all the dough we spend on cigarettes. But it’s not easy. It’s all we have left, since we’ve stopped going out and we’ve given up booze. It’s our only pleasure these days. (Melina, woman aged 54, unemployed) If you’ve got no money, you just stay at home and don’t budge. Smoking is my only relaxation. Going places, eating out, having fun is too expensive. Look at the people who go to football and rugby matches. That costs as much as a pack of cigarettes, if not two or three times more. (…) Plus the cost of getting there. Smoking is all we have! It’s our only way of relaxing. (Joseph, man age 50, unemployed)When I used to work for a building firm, I smoked less. But now it’s hard to find a job. (…) Smoking helps me. When I wake up in the night I can’t sleep anymore. So I smoke. What else to do? Nothing. I smoke. And if I ain’t got cigarettes, then… That’s bad! (…) There is also loneliness. Loneliness makes you smoke. (Clement, man aged 51, unemployed)Smoking. Sometimes I tell myself it’s all I have. Why? Because there was a big upheaval in my life. My smoking increased because of that upheaval (...) I was smoking already, but the upheaval made it worse: suddenly being myself on my own. Cigarettes keep me company. If I haven’t got any, I feel a craving, and they do actually keep me company. They are there, they are there. That’s it. When I smoke I’m less alone. Well I mean... it’s hard to admit, but I feel less lonely. (Solange, woman aged 49, unemployed)I started smoking when I stopped cocaine. (…) I restarted smoking when I lost my job and found myself out on the street. (…) I had no income so I cadged off people. Smoking calmed me down. (Karine, woman aged 28, unemployed)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- WHO, Tobacco Control Country Profiles; Shafey, O; Dolwick, S; Guindon, GE (Eds.) American Cancer Society, Inc: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2003.

- Peto, R; Lopez, A; Boreham, J; Thun, M. Mortality from smoking in developed countries 1950–2000, 2nd ed; Oxford University Press: New York, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp, P; Fenoglio, P. Le coût social des drogues licites (alcool et tabac) et illicites en France [The social cost of alcohol, tobacco and illegal drugs in France]; OFDT: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Peretti-Watel, P; Wilquin, JL; Beck, F. Les Français et la cigarette en 2005: un divorce pas encore consommé [Cigarette and the French in 2005: a divorce in progress]. In Attitudes et comportements de santé, Baromètre Santé 2005 [Health attitudes and behaviours, 2005 Health Barometer]; Beck, F, Guilbert, P, Gautier, A, Eds.; INPES: Saint-Denis, France, 2008; pp. 76–110. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, A; McKay, S. Poor smokers; PSI Publishing: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferis, BJ; Power, C; Graham, H; Manor, O. Changing social gradients in cigarette smoking and cessation over two decades of adult follow-up in a British birth cohort. J. Public Health 2004, 26, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cavelaars, AE; Kunst, AE; Geurts, JJ; Crialesi, R; Grötvedt, L; Helmert, U; Lahelma, E; Lundberg, O; Matheson, J; Mielck, A; Rasmussen, NK; Regidor, E; Rosario-Giraldes, M; Spuhler, T; Mackenbach, JP. Educational differences in smoking: international comparison. Br. Med. J 2000, 320, 1102–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Giskes, K; Kunst, AE; Benach, J; Borrell, C; Costa, G; Dahl, E; Dalstra, JAA; Federico, B; Helmert, U; Judge, K; Lahelma, E; Moussa, K; Ostergen, PO; Platt, S; Prattala, R; Rasmussen, NK; Mackenbach, JP. Trends in smoking behaviour between 1985 and 2000 in nine European countries by education. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 395–401. [Google Scholar]

- Federico, B; Kunst, AE; Vannoni, F; Damiani, G; Costa, G. Trends in educational inequalities in smoking in northern, mid and southern Italy, 1980–2000. Prev. Med 2004, 39, 919–926. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, P; Jerant, AF; Leigh, P; Lee, D; Chiem, A; Lewis, I; Lee, S. Cigarette prices, smoking, and the Poor: implications of recent trends. Am J Public Health 2007, 97, 1873–1877. [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau, EM; Krieger, N; Soobader, MJ. Working class matters: socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A; Sartor, C; Pergadia, ML; Huizink, AC; Lynskey, MT. Correlates of smoking cessation in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. Addict. Behav 2008, 33, 1223–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Remler, DK. Poor smokers, poor quitters, and cigarette tax regressivity. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, DM; Warner, KE. Smokers who have not quit: is cessation more difficult and should we change our strategies? In Those who continue to smoke, Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No 15; US Department of health and human services: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2003; pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, M. Why people smoke. Br. Med. J 2004, 328, 277–279. [Google Scholar]

- Guilbert, P; Baudier, F; Gautier, A; Goubert, AC; Arwidson, P; Janvrin, MP. Baromètre santé 2000, Méthode; CFES: Vanves, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, F; Guilbert, P. Baromètres santé: un éclairage sur leur méthode et leur évolution [Health Barometers: some insights into their methodology and evolution]. In Attitudes et comportements de santé, Baromètre Santé 2005 [Health attitudes and behaviours, 2005 Health Barometer]; Beck, F, Guilbert, P, Gautier, A, Eds.; INPES: Saint-Denis, France, 2008; pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton, TF; Kozlowski, LT; Frecker, RC; Fagerstrom, KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br. J. Addict 1991, 86, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Ikard, F; Green, DE; Horn, D. A scale to differentiate between types of smoking as related to the management of affect. Int. J. Addict 1969, 4, 649–659. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, G. The Poor. In Georg Simmel on Individuality and Social Forms; Levine, DN, Ed.; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B; Strauss, A. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research; Aldin: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A; Corbin, J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kenkel, D; Lillard, DR; Mathios, A. Smoke or fog? The usefulness of retrospectively reported information about smoking. Addiction 2003, 98, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Peretti-Watel, P. Pricing policy and some other predictors of smoking behaviours: an analysis of French retrospective data. Int. J. Drug Policy 2005, 16, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, D. The imperative of health: public health and the regulated body; Sage: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, J. Learning to Smoke: Tobacco Use in the West; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, H. Women’s smoking and family health. Soc. Sci. Med 1987, 25, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stead, M; MacSkill, S; MacKintosh, A; Reece, J; Eadie, D. It's as if you’re locked in: Qualitative explanations for area effects on smoking in disadvantaged communities. Health Place 2001, 7, 333–343. [Google Scholar]

- McKie, L; Laurier, E; Taylor, RJ; Lennox, AS. Eliciting the smoker’s agenda: implications for policy and practice. Soc. Sci. Med 2003, 56, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hoggart, R. The uses of Literacy: Aspects of Working-Class Life with Special Reference to Publications and Entertainments; Chatto & Windus: London, UK, 1957. [Google Scholar]

| Poor smokers (N=115) | Other smokers (N=506) | |

|---|---|---|

| row percentages | ||

| Gender | ||

| -women | 56% | 44% |

| -men | 44% | 56% * |

| Age (in years) | ||

| -18–24 | 10% | 20% |

| -25–34 | 29% | 27% |

| 35–49 | 40% | 32% |

| 50–64 | 20% | 17% |

| 65–75 | 1% | 4% # |

| Occupation: | ||

| -manual worker / clerk | 66% | 47% |

| -other | 34% | 53% *** |

| Educational level: | ||

| -< high-school | 75% | 52% |

| -≥ high-school | 25% | 48% *** |

| Monthly household income: † | ||

| -< 1,500 € | 49% | 14% |

| - ≥ 1,500 € | 51% | 86% *** |

| Single parent: | ||

| -no | 84% | 94% |

| -yes | 16% | 6% ** |

| Poor smokers (N=115) | Other smokers (N=506) | |

|---|---|---|

| row percentages and means | ||

| Daily cigarette consumption | ||

| - 1 to 5 cigarettes | 12% | 20% |

| - 6 to 10 cigarettes | 35% | 33% |

| - 11 to 20 cigarettes | 32% | 35% |

| - > 20 cigarettes | 21% | 12% * |

| Tobacco dependency (Fagerström): | ||

| - none / mild / moderate | 54% | 72% |

| - strong | 46% | 28% *** |

| Smoking less cigarettes since the cigarette price increase | ||

| -no | 63% | 66% |

| -yes | 37% | 34% ns |

| Smoking cheaper or hand-rolled cigarettes since the cigarette price increase | ||

| -no | 50% | 67% |

| -yes | 50% | 33% *** |

| Smoking motives (scale of 1 to 10): | ||

| -automatic smoking | 6.7 | 5.2 *** |

| -aid to socialisation | 4.4 | 6.9 *** |

| -enjoyment | 6.7 | 6.4 ns |

| -stress relief | 6.4 | 5.8 # |

| -improvement in concentration | 1.9 | 2.6 * |

| -to take one’s mind off cares and worries | 4.4 | 3.7 # |

| -weight control | 2.1 | 2.2 ns |

Share and Cite

Peretti-Watel, P.; Constance, J. “It’s All We Got Left”. Why Poor Smokers are Less Sensitive to Cigarette Price Increases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 608-621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6020608

Peretti-Watel P, Constance J. “It’s All We Got Left”. Why Poor Smokers are Less Sensitive to Cigarette Price Increases. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2009; 6(2):608-621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6020608

Chicago/Turabian StylePeretti-Watel, Patrick, and Jean Constance. 2009. "“It’s All We Got Left”. Why Poor Smokers are Less Sensitive to Cigarette Price Increases" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 6, no. 2: 608-621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6020608

APA StylePeretti-Watel, P., & Constance, J. (2009). “It’s All We Got Left”. Why Poor Smokers are Less Sensitive to Cigarette Price Increases. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 6(2), 608-621. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6020608