Integrating Surveillance and Stakeholder Insights to Predict Influenza Epidemics: A Bayesian Network Study in Queensland, Australia

Highlights

- The study addresses the ongoing global public health challenge of seasonal influenza by using a Bayesian Network (BN) model to examine how surveillance data, population characteristics, and contextual risk factors interact to influence epidemic occurrence in Queensland.

- The BN framework captures the complexity and uncertainty inherent in influenza transmission and epidemic emergence, potentially contributing to the planning and preparedness for infectious disease outbreaks.

- The study demonstrates that a BN-based approach, integrating surveillance data, environmental/climatic indicators with expert and stakeholder knowledge, enhances epidemic risk estimation and response.

- The findings provide a transparent and interpretable modelling framework that quantifies uncertainty and supports evi-dence-informed decision-making in influenza preparedness.

- Public health practitioners can apply the BN model to explore “what-if” scenarios, identify high-risk regions and conditions, and guide targeted vaccination, travel risk management, and timely control measures.

- Policymakers and researchers may use the BN framework to support adaptive preparedness planning, evaluate intervention strategies under uncertainty, and extend the model to other climate-sensitive or emerging infectious diseases.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Develop a probabilistic BN model integrating surveillance, climatic, demographic, and expert-elicited data;

- Quantify conditional dependencies among key epidemic determinants;

- Evaluate model performance using retrospective surveillance data from Queensland;

- Conduct scenario analyses to examine how variable changes influence epidemic probability;

- Identify influential determinants through sensitivity analyses; and

- Demonstrate the model’s potential as an early-warning decision-support tool for infectious disease prevention and outbreak control.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

- Surveillance data: The weekly number of influenza notifications, including laboratory-confirmed influenza cases (by Queensland Hospital and Health Services), was obtained from Queensland Health’s influenza surveillance reports [30]. Additional surveillance data was sourced from WHO FluNet to inform viral circulation patterns in Australia over time, and this was used as a proxy to estimate Queensland patterns [31].

- Climate data: Daily temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), and rainfall (mm) were obtained from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology for representative stations in Southeast Queensland (Brisbane), Central Queensland (Rockhampton), and North Queensland (Cairns) [32].

- Epidemic definition: Based on Queensland Health’s notifiable conditions surveillance practice, we define an influenza epidemic as “the accumulated notifications of an observed season were exceeding the average notifications in 2011–2015 (baseline) by 10% in the same location” [36].

- Data structure: Weekly observations from all data sources were aligned by calendar week and region, producing 520 multi-variable records (52 weeks × 10 years) for model development and validation. Three documented prominent epidemic periods (2015, 2017, and 2019) were identified from surveillance reports and used for retrospective validation.

2.2. Bayesian Network Model Development

- Rainfall: Low (<50 mm/month), Moderate (50–150 mm), High (>150 mm) based on Queensland seasonal patterns.

- Age groups: <5, 5–65, >65 years to align with established risk categories used in Queensland influenza surveillance and vaccination prioritisation programs [45].

- Seasons: Mar–May, Jun–Aug, Sep–Nov, Dec–Feb. Seasons were included as a separate variable to represent southern hemisphere seasonality independent of climate variable discretisation.

2.2.1. Model Structure Development

- Expert workshops: Three half-day workshops with stakeholders (n = 5: epidemiologists, infectious disease physicians, public health officials, climate scientists) were utilised to validate proposed relationships, identify additional relevant variables specific to the Queensland context, and ensure the model’s scope aligned with decision-maker needs;

- Structural validation: Preliminary structure validation occurred through expert review for causal plausibility and alignment with domain knowledge; and

- Iterative refinement: The model structure was revised based on predictive performance, stakeholder feedback on interpretability, and computational feasibility.

2.2.2. Conditional Probability Table Construction Method

- Expert panel: Five experts participated in CPT elicitation: two epidemiologists (15+ years of experience in influenza surveillance), two infectious disease physicians (10+ years of clinical experience), and one climate scientist (25+ years of experience in climate-health interactions). Experts were selected based on their experience/involvement in influenza surveillance and public health response.

- Elicitation method: A consensus technique was employed over two rounds of workshops [49]. During round one, experts independently assessed “best case”, “typical case”, and “worst case” scenarios to anchor probability distributions for each CPT. Then, in round two, the experts revised estimates based on group responses and evidence. Any divergences exceeding 20% triggered facilitated discussion, and probability assignments were cross-checked for monotonicity and plausibility using the scientific literature.

- Consistency checks: The consistency checks comprised of three components, (1) Logical coherence, whereby CPTs were assessed for expected monotonicity (e.g., higher temperature should not arbitrarily increase epidemic probability); (2) The literature validation, which involved comparing probability distributions against empirical effect sizes from published studies where available; and (3) Sensitivity testing, where extreme CPT values were tested to ensure they produced logically consistent network outputs.

2.2.3. Scenario Analysis and Evidence Setting

2.3. BN Model Performance and Evaluation

- Model structure and CPTs: Developed through expert workshops using domain knowledge from the influenza transmission literature, Queensland surveillance patterns, and expert consensus.

- Historical data usage: Informed prior probabilities for observable nodes (e.g., seasonal distributions, regional patterns) and provided context for expert elicitation (typical vs. extreme scenarios) but did not train model parameters in a machine learning sense.

- Testing procedure: Since the BN model was developed based on expert knowledge rather than a data-driven (machine learning) model, GeNIe’s “Test Only” validation approach was used, which is specifically designed for expert knowledge-based models. This method is primarily used to assess the predictive performance of a BN model on a set of real-world observations.

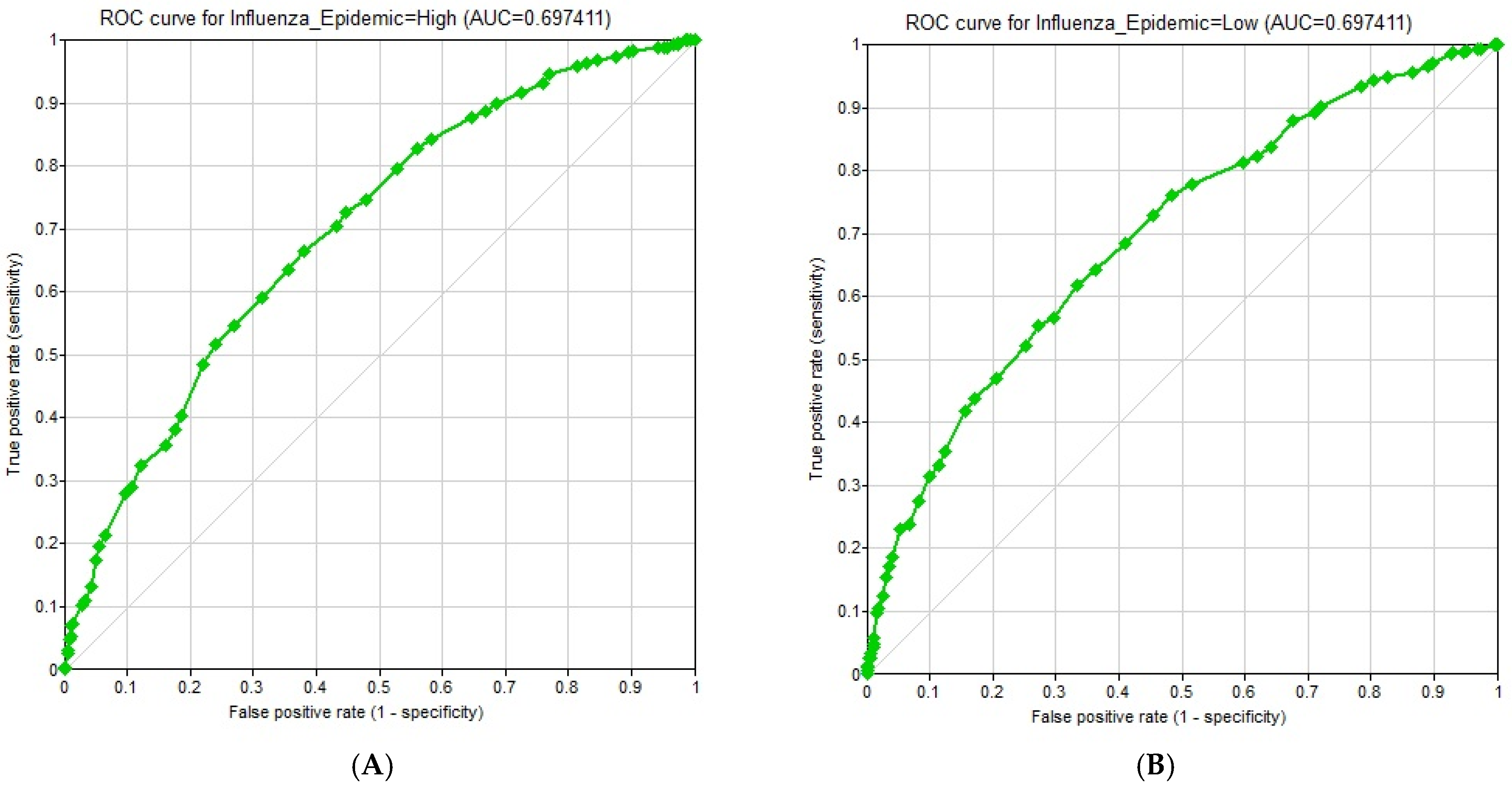

- Output metrics: (1) Accuracy, defined as the percentage of records for which the model correctly predicted the state of the Class Node; (2) Confusion matrix, a table containing the breakdown of correct and incorrect predictions for each state of the Class Node; (3) ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curves and corresponding AUC (Area Under the Curve) values, measuring the performance of the classifier across different decision thresholds; and (4) Sensitivity analysis, quantifying the influence of each variable on the probability of an influenza epidemic using Tornado diagrams. Relative influence values were also computed by measuring the maximum shift in posterior probability when each variable was fixed at its extreme states.

3. Results

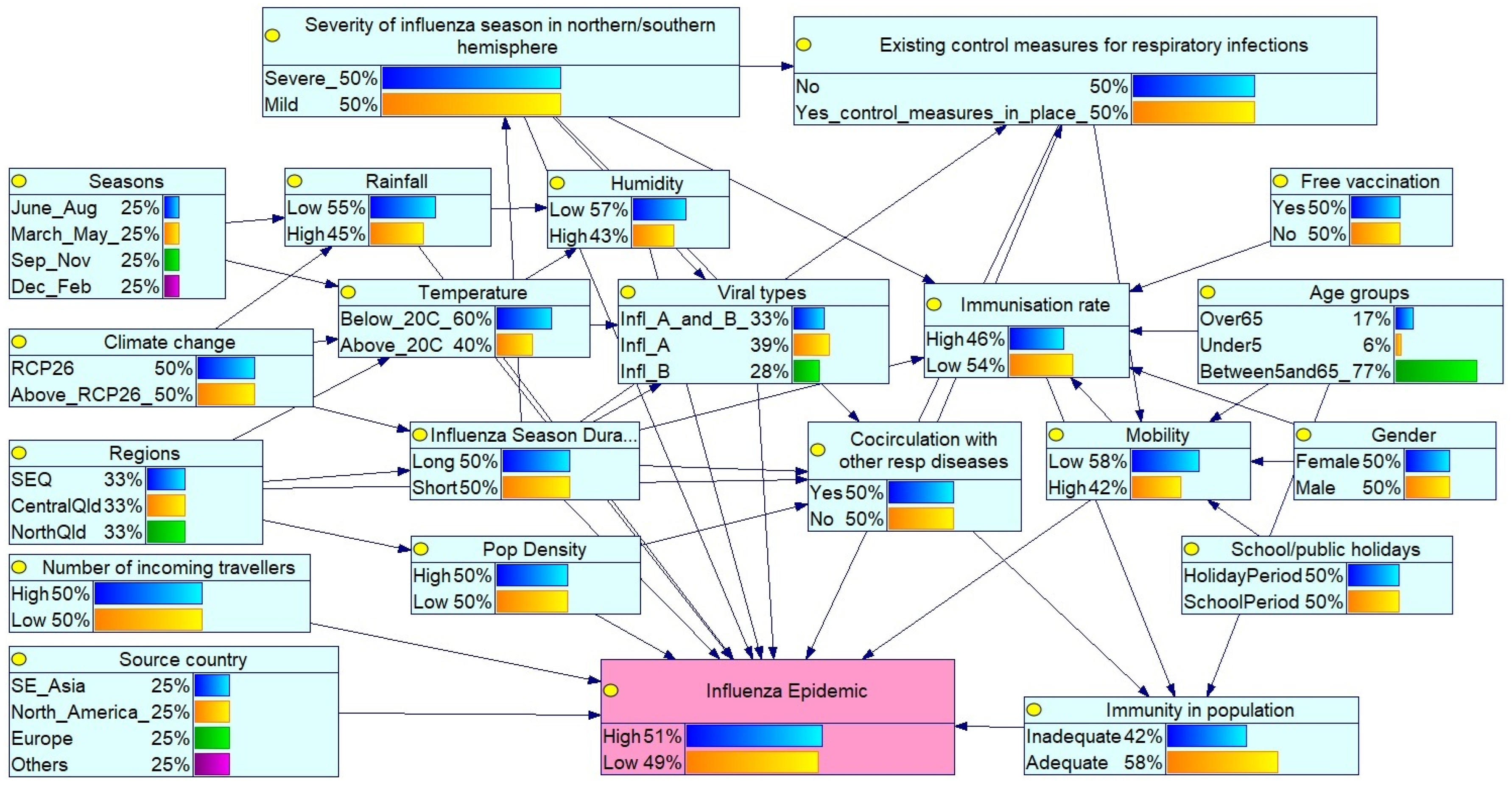

3.1. Bayesian Network for Influenza Epidemic Risk Assessment in Queensland

- Global influenza season: Severity in the northern/southern hemispheres reflects circulating virus types and virulence.

- Public health interventions: Existing control measures such as mask mandates, social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, travel restrictions, and influenza vaccination coverage affect transmission. Free vaccine availability influences the immunisation rates within the population, while increased incoming travellers reflect population mobility.

- Seasonality patterns: Seasons (Mar–May, Jun–Aug, Sep–Nov, Dec–Feb) reflect southern hemisphere influenza trends, with peak activity typically in winter (Jun–Aug). Influenza season duration (long or short) also modulates epidemic potential.

- Environmental/climatic conditions: Temperature, humidity and rainfall affect virus survival and transmission. Climate change, represented by RCP 2.6 and ≥RCP 2.6 scenarios, may alter seasonal dynamics.

- Geographical and demographic factors: Regions (Southeast Qld (SEQ), Central Qld, North Qld) capture climatic and population density variations. The selected Queensland regions represent different climatic zones according to their latitudinal gradients (temperate, subtropical, and tropical). The SEQ region is the most populous region in Queensland. The source country (SE_Asia (South East Asia), North America, Europe and Others) of the viral strain is also considered.

- Virological and host factors: Virus types (influenza A/B), age groups (under 5, 5–65, over 65), gender, and co-circulating respiratory pathogens (e.g., COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)) influence susceptibility and diagnosis. Mobility and school/public holidays also affect transmission dynamics.

- Population immunity: Determined by age, vaccination status, and prior exposure to influenza or other respiratory infections.

3.2. Scenario Analysis Results

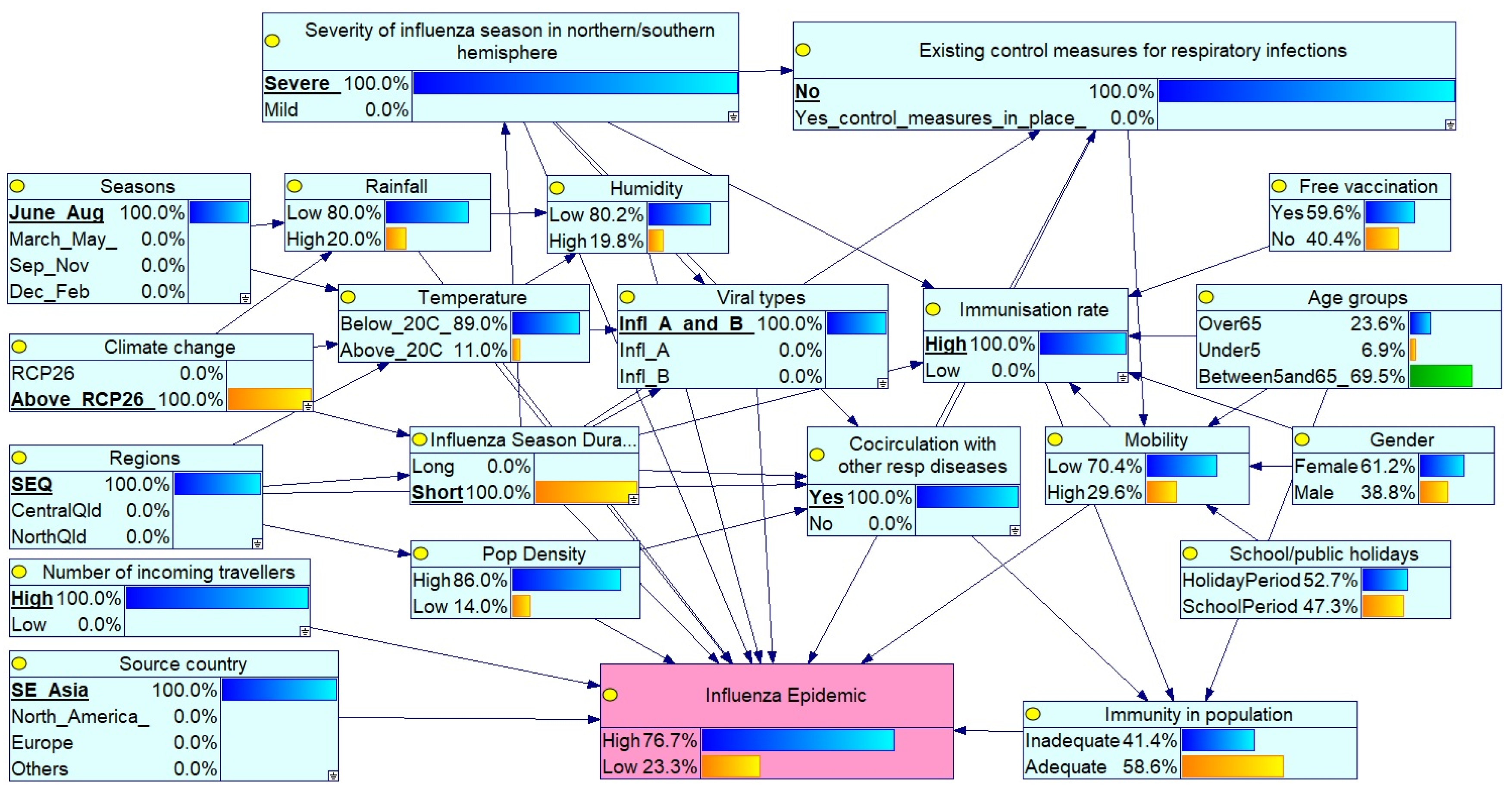

Scenario 1: Severe Peak Season Epidemic in SEQ with High Circulation and No Controls

3.3. Impact of Node Probability Changes on Epidemic Risk

- Severity of influenza season in northern/southern hemisphere: set to Severe, indicating widespread circulation of virulent strains.

- Existing control measures for respiratory infections: set to No, reflecting the absence of interventions such as mask mandates or social distancing.

- Seasons: set to June–August, aligning with peak influenza activity in the southern hemisphere (including Queensland).

- Climate change: set to above RCP 2.6, representing significant long-term climate shifts potentially affecting disease patterns.

- Regions: set to SEQ, focused on the SEQ Region.

- Co-circulation of respiratory pathogens: set to Yes, indicating simultaneous circulation of influenza A and B, along with other respiratory viruses (e.g., COVID-19 and RSV).

- Source country: set to Southeast Asia, suggesting a potential source of the influenza virus.

- Number of incoming travellers: set to High, reflecting elevated population mobility.

- Viral types: set to Influenza A and B co-circulation.

- Immunisation rate: set to High, indicating widespread vaccine coverage.

3.4. Comparison of Scenario Analysis Findings

- High epidemic risk under severe conditions: All nine scenarios, characterised by a severe global influenza season (100%), a peak influenza season (100%), co-circulation of influenza A and B with other respiratory infections (such as RSV and COVID-19), absence of control measures, and elevated climate change impact (above RCP 2.6), resulted in significantly higher epidemic probabilities (ranging from 63% to 86%) compared to the baseline (50.7%). These findings underscore the dominant influence of these overarching risk factors.

- Moderate influence of source country: Virus origin showed a modest impact. Under similar high-risk conditions, Scenario 1 (SE Asian origin, 76.7%) yielded a slightly higher epidemic probability than Scenario 2 (European origin, 71.5%), suggesting moderate regional differences in strain transmissibility or severity.

- Effect of control measures: The presence of public health interventions notably reduced epidemic risk. Scenario 4, which included control measures set to Yes, showed a lower probability (63%) compared to Scenario 2 (71.5%), where such measures were absent, highlighting the mitigating effect.

- Impact of vaccination rate: Lower vaccination rates consistently elevated risk. Scenario 3 (low vaccination coverage) showed an increase in probability to 80.6% compared to Scenario 1 (high vaccination coverage, 76.7%). Similar trends were observed in Scenarios 6 and 9, reinforcing the critical role of vaccination, but the risk also depends on the status of other factors.

- Season duration: A longer influenza season (Scenario 6) increased epidemic probability (82%) compared to a shorter season (Scenario 2, 71.5%), indicating a moderate effect when controlling for other factors.

- Number of incoming travellers: A higher traveller volume significantly increased epidemic risk. Scenario 8, with low traveller numbers, showed a reduced probability (74.9%) compared to Scenario 6 (82%), under otherwise identical conditions. This aligns with seasonal travel patterns in Australia, particularly during school and public holidays and northern hemisphere summer vacations.

- Regional differences: SEQ appears slightly more vulnerable than North Qld. Scenario 6 (SEQ, 74.1%) showed a higher probability than Scenario 7 (North Qld, 71.5%), even after accounting for vaccination effects, suggesting regional susceptibility linked to population density and connectivity.

3.5. Retrospective Validation Against Documented Epidemics

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis Results

3.7. Model Evaluation Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Applications of a Bayesian Network Model in Influenza Epidemics

4.3. Temporal Implementation and Real-Time Application

- Seasonal variables: The “Season” node explicitly represents time of year, which is the primary temporal determinant of influenza risk in temperate and subtropical regions.

- Sequential updating: The model can be updated with new surveillance data on a weekly or bi-weekly cycle to provide time-varying risk estimates that reflect changing conditions.

- Rolling forecasts: By incorporating recent surveillance trends as evidence, the model can generate updated forecasts that implicitly account for recent epidemic trends.

4.4. Limitations of the Model and Sources of Uncertainty

- Temporal dynamics: The static BN does not explicitly model epidemic growth dynamics, temporal autocorrelation, or generation intervals. Consequently, the epidemic probability represents instantaneous risk under current conditions rather than the forward projection of case trajectories over multiple weeks.

- Independence assumptions: The BN assumes conditional independence given parent nodes. Some relationships may exhibit dependencies not captured by the current structure (e.g., complex interactions between climate variables beyond parent–child relationships).

- Simplified relationships: Continuous variables were discretised into categorical states, potentially losing information about non-linear relationships or threshold effects within categories.

4.5. Implications for Public Health Practice

4.6. Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Macias, A.E.; McElhaney, J.E.; Chaves, S.S.; Nealon, J.; Nunes, M.C.; Samson, S.I.; Seet, B.T.; Weinke, T.; Yu, H. The disease burden of influenza beyond respiratory illness. Vaccine 2021, 39, A6–A14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyeki, T.M.; Hui, D.S.; Zambon, M.; Wentworth, D.E.; Monto, A.S. Influenza. Lancet 2022, 400, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Influenza (Seasonal). 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal) (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Tamerius, J.D.; Shaman, J.; Alonso, W.J.; Bloom-Feshbach, K.; Uejio, C.K.; Comrie, A.; Viboud, C. Environmental predictors of seasonal influenza epidemics across temperate and tropical climates. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003194, Correction in PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9. https://doi.org/10.1371/annotation/df689228-603f-4a40-bfbf-a38b13f88147.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, I.; Kiciman, E.; Elliot, J.W.; Shaman, J.L.; Rzhetsky, A. Conjunction of factors triggering waves of seasonal influenza. eLife 2018, 7, e30756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalziel, B.D.; Kissler, S.; Gog, J.R.; Viboud, C.; Bjørnstad, O.N.; Metcalf, C.J.E.; Grenfell, B.T. Urbanization and humidity shape the intensity of influenza epidemics in U.S. cities. Science 2018, 362, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowen, A.C.; Steel, J. Roles of humidity and temperature in shaping influenza seasonality. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 7692–7695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peci, A.; Winter, A.-L.; Li, Y.; Gnaneshan, S.; Liu, J.; Mubareka, S.; Gubbay, J.B. Effects of absolute humidity, relative humidity, temperature, and wind speed on influenza activity in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e02426-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paynter, S. Humidity and respiratory virus transmission in tropical and temperate settings. Epidemiol. Infect. 2015, 143, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dave, K.; Lee, P.C. Global geographical and temporal patterns of seasonal influenza and associated climatic factors. Epidemiol. Rev. 2019, 41, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamerius, J.; Uejio, C.; Koss, J. Seasonal characteristics of influenza vary regionally across US. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Zviedrite, N.; Uzicanin, A. Effectiveness of workplace social distancing measures in reducing influenza transmission: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X.; Cao, K.; Du, Y.; Jiang, D.; Yan, R.; Wu, X.; Chen, M.; You, Y.; et al. Social contact patterns with acquaintances and strangers related to influenza in the post-pandemic era. J. Public Health 2025, 33, 2387–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earn, D.J.D.; He, D.; Loeb, M.B.; Fonseca, K.; Lee, B.E.; Dushoff, J. Effects of school closure on incidence of pandemic influenza in Alberta, Canada. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 156, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charu, V.; Zeger, S.; Gog, J.; Bjørnstad, O.N.; Kissler, S.; Simonsen, L.; Grenfell, B.T.; Viboud, C. Human mobility and the spatial transmission of influenza in the United States. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitmeyer, K.; Adlhoch, C. Review article: Influenza transmission on aircraft. Epidemiology 2016, 27, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goeijenbier, M.; van Genderen, P.; Ward, B.J.; Wilder-Smith, A.; Steffen, R.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E. Travellers and influenza: Risks and prevention. J. Travel Med. 2016, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.T.; Cowling, B.J. Influenza virus: Tracking, predicting, and forecasting. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Box, G.E.P.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C.; Ljung, G.M. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-118-67502-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.; Koehler, A.; Ord, K.; Snyder, R. Forecasting with Exponential Smoothing: The State Space Approach; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; ISBN 978-3-540-71916-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chretien, J.-P.; George, D.; Shaman, J.; Chitale, R.A.; McKenzie, F.E. Influenza forecasting in human populations: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, N.G.; Brooks, L.C.; Fox, S.J.; Kandula, S.; McGowan, C.J.; Moore, E.; Osthus, D.; Ray, E.L.; Tushan, A.; Yamana, T.K.; et al. A collaborative multiyear, multimodel assessment of seasonal influenza forecasting in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3146–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Atangana, A. Modeling the dynamics of novel coronavirus (2019-nCov) with fractional derivative. Alex. Eng. J. 2020, 59, 2379–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcot, B.G.; Penman, T.D. Advances in Bayesian network modelling: Integration of modelling technologies. Environ. Model. Softw. 2019, 111, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, N.; Neil, M. Risk Assessment and Decision Analysis with Bayesian Networks, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-131-526-940-5. [Google Scholar]

- Koseoglu Balta, G.C.; Dikmen, I.; Birgonul, M.T. Bayesian network based decision support for predicting and mitigating delay risk in TBM tunnel projects. Autom. Constr. 2021, 129, 103819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korb, K.B.; Nicholson, A.E. Bayesian Artificial Intelligence, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4398-1591-5. [Google Scholar]

- Aronis, J.M.; Ye, Y.; Espino, J.; Hochheiser, H.; Michaels, M.G.; Cooper, G.F. A Bayesian system to detect and track outbreaks of influenza-like illnesses including novel diseases: Algorithm development and validation. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024, 10, e57349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, W.M.D.; Simelane, S.P.; Nhlabatsi, N.M. Bayesian network-based spatial predictive modelling reveals COVID-19 transmission dynamics in Eswatini. Spat. Inf. Res. 2022, 30, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queensland Health. Acute Respiratory Infection Surveillance Reporting: Weekly Influenza, Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), and COVID-19. 2025. Available online: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/clinical-practice/guidelines-procedures/diseases-infection/surveillance/reports/flu (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- WHO. Global Influenza Programme. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/flunet (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Bureau of Meteorology. Climate Data Online. 2025. Available online: https://www.bom.gov.au/climate/data/index.shtml (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Regional Population, 2020–2021 Financial Year. 2022. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional-population/2020-21 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- ABS. Overseas Arrivals and Departures, Australia. 2025. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/tourism-and-transport/overseas-arrivals-and-departures-australia/latest-release#:~:text=Key%20statistics,-September%202020%20original&text=Overseas%20visitor%20arrivals%20to%20Australia,previous%20month%20to%208%2C170%20trips (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- ABS. Region Summary: Queensland. 2025. Available online: https://dbr.abs.gov.au/region.html?lyr=ste&rgn=3 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Queensland Health. Notifiable Conditions Weekly Totals. 2025. Available online: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/clinical-practice/guidelines-procedures/diseases-infection/surveillance/reports/notifiable/weekly (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Cain, J.D. Planning Improvements in Natural Resources Management: Guidelines for Using Bayesian Networks to Support the Planning and Management of Development Programmes in the Water Sector and Beyond; Centre for Ecology and Hydrology: Wallingford, UK, 2001; ISBN 090-374-100-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kjærulff, U.B.; Madsen, A.L. Bayesian Networks and Influence Diagrams: A Guide to Construction and Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York City, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4614-5104-4. [Google Scholar]

- Marcot, B.G. Common quandaries and their practical solutions in Bayesian network modeling. Ecol. Model. 2017, 358, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.H.; Pollino, C.A. Good practice in Bayesian network modelling. Environ. Model. Softw. 2012, 37, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakeman, A.J.; Letcher, R.A.; Norton, J.P. Ten iterative steps in development and evaluation of environmental models. Environ. Model. Softw. 2006, 21, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, T.; Riley, S.; Barr, I.G.; Broor, S.; Chadha, M.; Cox, N.J.; Daniels, R.S.; Gunasekaran, C.P.; Hunt, A.C.; Kelso, A.; et al. Global circulation patterns of seasonal influenza viruses vary with antigenic drift. Nature 2015, 523, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelman, B.S.; Viboud, C.; Koelle, K.; Ferrari, M.J.; Bharti, N.; Grenfell, B.T. Global patterns in seasonal activity of influenza A/H3N2, A/H1N1, and B from 1997 to 2005: Viral coexistence and latitudinal gradients. PLoS ONE 2007, 12, e1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Lin, Y.; Yang, J.; Fang, K.; Wu, J.; Zheng, M. Global variability of influenza activity and virus subtype circulation from 2011 to 2023. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2023, 10, e001638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queensland Health. Influenza in Queensland 2013–2018: Influenza Surveillance Report; Queensland Health: Brisbane, Australia, 2019.

- Shaman, J.; Kohn, M. Absolute humidity modulates influenza survival, transmission, and seasonality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3243–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaman, J.; Pitzer, V.E.; Viboud, C.; Grenfell, B.T.; Lipsitch, M. Absolute Humidity and the seasonal onset of influenza in the continental United States. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000316, Correction in PLoS Biol. 2010, 8. https://doi.org/10.1371/annotation/35686514-b7a9-4f65-9663-7baefc0d63c0.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., Mintenbeck, K., Algería, A., Nicolai, M., Okem, A., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York City, NY, USA, 2019; Summary for Policymakers; pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanea, A.M.; Wilkinson, D.P.; McBride, M.; Lyon, A.; van Ravenzwaaij, D.; Singelton Thorn, F.; Gray, C.; Mandel, D.R.; Willcox, A.; Gould, E.; et al. Mathematically aggregating experts’ predictions of possible futures. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeNIe Modeler, version 5.0.R2; BayesFusion: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2024.

- Newman, L.P.; Bhat, N.; Fleming, J.A.; Neuzil, K.M. Global influenza seasonality to inform country-level vaccine programs: An analysis of WHO FluNet influenza surveillance data between 2011 and 2016. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemey, P.; Rambaut, A.; Bedford, T.; Faria, N.; Bielejec, F.; Baele, G.; Russell, C.A.; Smith, D.J.; Pybus, O.G.; Brockmann, D.; et al. Unifying viral genetics and human transportation data to predict the global transmission dynamics of human influenza H3N2. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1003932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; Hassan, M.Z. Seasonal influenza surveillance and vaccination policies in the WHO South-East Asian Region. BMJ Glob. Health 2025, 10, e017271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Members of the Western Pacific Region Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System. Epidemiological and virological characteristics of influenza in the Western Pacific Region of the World Health Organization, 2006–2010. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37568. [CrossRef]

- WHO Europe. How Pandemic Influenza Emerges. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/how-pandemic-influenza-emerges (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). How Flu Viruses Can Change: “Drift” and “Shift”. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/php/viruses/change.html (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Madewell, Z.J.; Wong, J.M.; Thayer, M.B.; Rivera-Amill, V.; Sainz de la Pena, D.; Pasarell, J.B.; Paz-Bailey, G.; Adams, L.E.; Yang, Y. Population-level respiratory virus-virus interactions, Puerto Rico, 2013-2023. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 154, 107878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirreff, G.; Chaves, S.S.; Coudeville, L.; Mengual-Chuliá, B.; Mira-Iglesias, A.; Puig-Barberà, J.; Orrico-Sanchez, A.; Díez-Domingo, J.; Valencia Hospital Surveillance Network for the Study of Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. Seasonality and co-detection of respiratory viral infections among hospitalised patients admitted with acute respiratory illness-Valencia Region, Spain, 2010–2021. Influenza Respir. Viruses 2024, 18, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, H.H.; Fall, A.; Norton, J.M.; Sachithanandham, J.; Yunker, M.; Abdullah, O.; Hanlon, A.; Gluck, L.; Morris, C.P.; Pekosz, A.; et al. Respiratory virus disease and outcomes at a large academic medical center in the United States: A retrospective observational study of the early 2023/2024 respiratory viral season. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0111624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Centre for Disease Control. Australian National Surveillance Plan for COVID-19, Influenza, and RSV. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov.au/system/files/2025-09/australian-national-surveillance-plan-for-covid-19-influenza-and-rsv.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Feng, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Q.; Xie, Y.; Peng, Z.; Zheng, J.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, M.; Lai, S.; Wang, D.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreaks and interventions on influenza in China and the United States. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hills, T.; Kearns, N.; Kearns, C.; Beasley, R. Influenza control during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020, 396, 1633–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Viboud, C.; Petersen, E. Understanding the rebound of influenza in the post COVID-19 pandemic period holds important clues for epidemiology and control. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 122, 1002–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jia, M.; Jiang, M.; Cao, Y.; Dai, P.; Yang, J.; Yang, X.; Xu, Y.; Yang, W.; Feng, L. Increased population susceptibility to seasonal influenza during the COVID-19 pandemic in China and the United States. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e29186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.J.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Budd, A.P.; Brammer, L.; Sullivan, S.; Pineda, R.F.; Cohen, C.; Fry, A.M. Decreased influenza activity during the COVID-19 pandemic-United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. Am. J. Transpl. 2020, 20, 3681–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamerius, J.; Nelson, M.I.; Zhou, S.Z.; Viboud, C.; Miller, M.A.; Alonso, W.J. Global influenza seasonality: Reconciling patterns across temperate and tropical regions. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moa, A.M.; Adam, D.C.; MacIntyre, C.R. Inter-seasonality of influenza in Australia. Influenza Respir. Viruses 2019, 13, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, E.J.; Malo, J.; Vette, K.; Nimmo, G.R.; Lambert, S.B. Evidence for an increase in the intensity of inter-seasonal influenza, Queensland, Australia, 2009-2019. Influenza Respir. Viruses 2021, 15, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascaro, S.; Wu, Y.; Woodberry, O.; Nyberg, E.P.; Pearson, R.; Ramsay, J.A.; Mace, A.O.; Foley, D.A.; Snelling, T.L.; Nicholson, A.E.; et al. Modeling COVID-19 disease processes by remote elicitation of causal Bayesian networks from medical experts. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2023, 23, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, A.; Di Giuseppe, G.; Gupta, A.; Poirier, A.; Arora, P. Bayesian network modelling study to identify factors influencing the risk of cardiovascular disease in Canadian adults with hepatitis C virus infection. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, O.; Hadwen, W.L.; Buckwell, A.; Fleming, C.; Ware, D.; Smart, J.C.R.; Dan, A.; Mackey, B. Assessing how ecosystem-based adaptations to climate change influence community wellbeing: A Vanuatu case study. Reg. Environ. Change 2021, 21, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viboud, C.; Bjørnstad, O.N.; Smith, D.L.; Simonsen, L.; Miller, M.A.; Grenfell, B.T. Synchrony, waves, and spatial hierarchies in the spread of influenza. Science 2006, 312, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K.P. Dynamic Bayesian Networks: Representation, Inference and Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Khalifa, M.; Albadawy, M. Using artificial intelligence in academic writing and research: An essential productivity tool. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. Update 2024, 5, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagno, M.; Taccone, F.S.; Gerli, A.G. Can artificial intelligence help for scientific writing? Crit. Care 2023, 27, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Rank | Scenario | Epidemic Probability (95% CI) | Key Characteristics | Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Scn 9 | 86.0% (81.2–90.1%) | SE Asian origin, SEQ | No control measures, Number of incoming travellers (High 100%), Long season, Low immunisation |

| 2 | Scn 6 | 82.0% (76.8–86.5%) | European origin, SEQ | No control measures, Number of incoming travellers (High 100%), Long season, Low immunisation |

| 3 | Scn 3 | 80.6% (75.1–85.4%) | SE Asian origin, SEQ | No control measures, Number of incoming travellers (High 100%), Short season, Low immunisation |

| 4 | Scn 1 | 76.7% (71.2–81.8%) | SE Asian origin, SEQ | No control measures, Number of incoming travellers (High 100%), Short season, High immunisation |

| 5 | Scn 8 | 74.9% (69.1–80.2%) | European origin, SEQ | No control measures, Number of incoming travellers (Low 100%), Long season, Low immunisation |

| 6 | Scn 7 | 74.1% (68.5–79.3%) | European origin, North Qld | No control measures, Number of incoming travellers (High 100%), Long season, High immunisation |

| 7 | Scn 2 | 71.5% (65.8–76.9%) | European origin, SEQ | No control measures, Number of incoming travellers (High 100%), Short season, High immunisation |

| 8 | Scn 5 | 64.4% (58.6–70.1%) | SE Asian origin, SEQ | Yes control measures, Number of incoming travellers (High 50%), Short season, High immunisation |

| 9 | Scn 4 | 63.0% (57.1–68.7%) | European origin, SEQ | Yes control measures, Number of incoming travellers (High 100%), Short season, High immunisation |

| 10 | Baseline | 50.7% (47.2–54.3%) | Baseline | No certainties, balanced status across variables |

| Year | Epidemic Period | Region | Model-Predicted Probability (95% CI) | Observed Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Jul–Sep | SEQ | 65.3% (58.2–72.1%) | Epidemic |

| 2017 | Jun–Aug | SEQ | 73.8% (67.4–79.5%) | Epidemic |

| 2019 | Jul–Oct | Multiple | 71.2% (64.8–77.3%) | Epidemic |

| Rank | Variable Combination | Effect | Influence Type | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Number of incoming travellers = High | Strongest (~50.3% to 51.2%) | Heavily Positive | High traveller volumes create a constant influx of diverse viral strains, challenging local containment. |

| 2 | Severity of influenza season in northern/southern hemisphere = Severe + Influenza season = Long | Very Strong (~50.4% to 51.0%) | Heavily Positive | When both hemispheres experience severe seasons with long durations (e.g., overlapping seasons), it facilitates high viral loads beyond the usual season. |

| 3 | Population density = High + Regions = SEQ | Strong (~50.4% to 50.9%) | Heavily Positive | Southeast Queensland’s high population density facilitates viral transmission through public transport, shopping centres, childcare centres, and workplaces. |

| 4 | Humidity = Low + Temperature = Below 20 °C + Rainfall = Low | Moderate-Strong (~50.5% to 50.9%) | Moderately Positive | Cool, dry conditions are in favour of influenza viral survival and transmission. |

| 5 | Control measures = No + Short season + No co-circulation + Mild severity | Moderate (~50.5% to 50.85%) | Positive | Absence of control measures is a key driver enabling the spread of influenza despite seemingly “mild” conditions. |

| 6 | Season = Dec–Feb | Moderate (~50.5% to 50.9%) | Moderately Negative | December-February (summer in Australia) acts as nature’s “viral circuit breaker”. High temperatures and humidity during summer suppress influenza activity. |

| 7 | Long season + Climate change > RCP 2.6 + North Qld | Low-Moderate (~50.5% to 50.85%) | Positive | Long-term climate change may disrupt traditional seasonal patterns, especially in tropical North Qld, making influenza transmission patterns more complex and unpredictable. With prolonged seasons in this tropical region, mild summer influenza clusters may trigger large outbreaks. |

| 8 | Long season + Climate change > RCP 2.6 + Central Qld | Low-Moderate (~50.6% to 50.9%) | Slightly Positive | Influenza seasonality patterns in Central Queensland are complex due to its mixed climate conditions (subtropical and some tropical). Under the influence of long-term climate change, this location may experience more unpredictable influenza transmission patterns, potentially extending traditional influenza seasons. |

| 9 | Season = June–Aug | Lower (~50.6% to 50.7%) | Weakly Positive | Expected seasonal influenza peaks coincide with winter months. |

| 10 | Source country = Others | Lowest (~50.6% to 50.7%) | Negative | The negative effect suggests these sources may indicate contained, traceable outbreaks rather than community spread. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sahin, O.; Phung, H.; Standke, A.; Rajmokan, M.; Raulli, A.; York, A.; Lee, P. Integrating Surveillance and Stakeholder Insights to Predict Influenza Epidemics: A Bayesian Network Study in Queensland, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010069

Sahin O, Phung H, Standke A, Rajmokan M, Raulli A, York A, Lee P. Integrating Surveillance and Stakeholder Insights to Predict Influenza Epidemics: A Bayesian Network Study in Queensland, Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010069

Chicago/Turabian StyleSahin, Oz, Hai Phung, Andrea Standke, Mohana Rajmokan, Alex Raulli, Amy York, and Patricia Lee. 2026. "Integrating Surveillance and Stakeholder Insights to Predict Influenza Epidemics: A Bayesian Network Study in Queensland, Australia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010069

APA StyleSahin, O., Phung, H., Standke, A., Rajmokan, M., Raulli, A., York, A., & Lee, P. (2026). Integrating Surveillance and Stakeholder Insights to Predict Influenza Epidemics: A Bayesian Network Study in Queensland, Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010069