Impact of Social Determinants of Health on the Incidence of Tuberculosis in Central Asia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

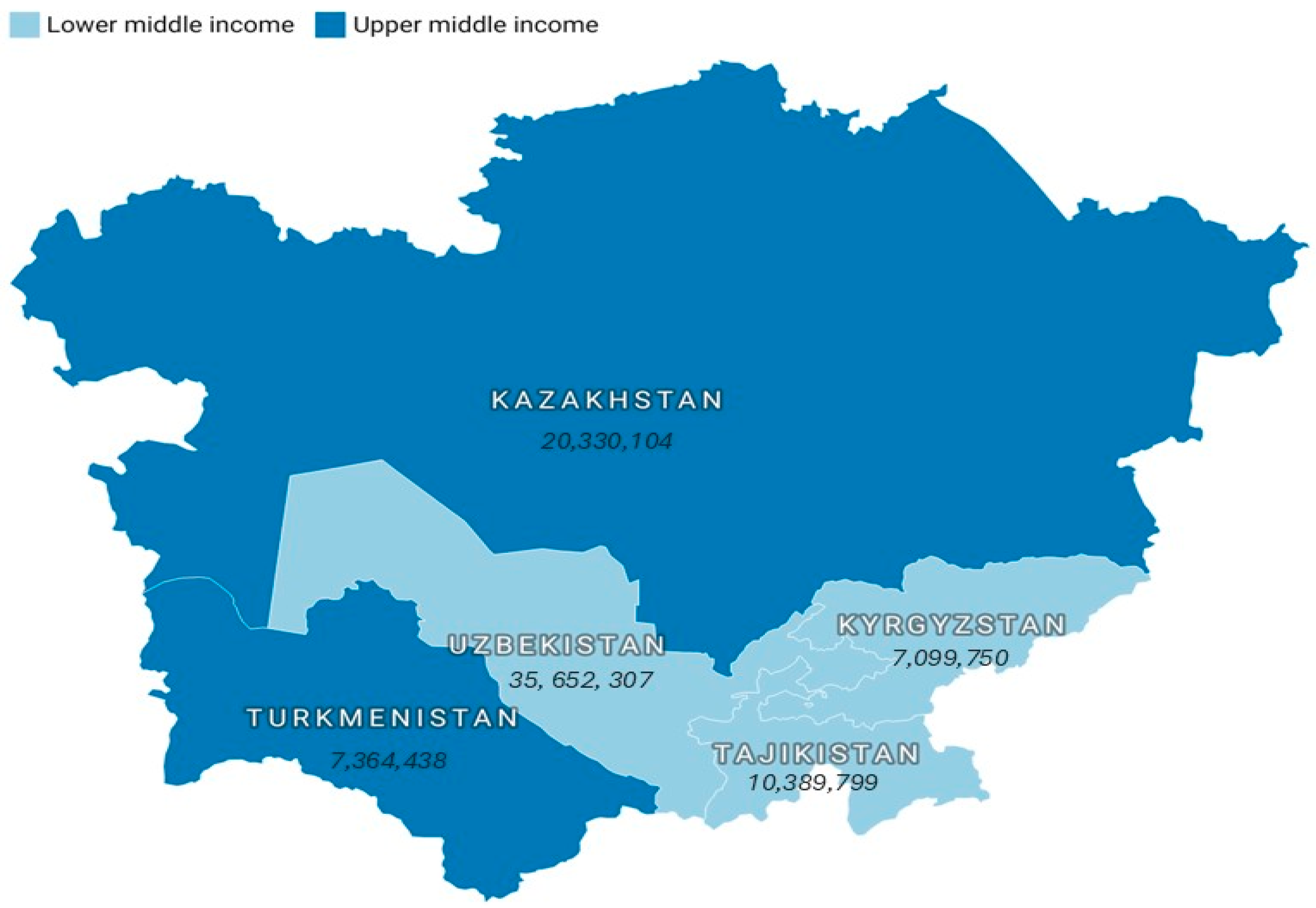

2.1. Countries Examined

2.2. Data Origins

2.3. Variables Investigated

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethics Statement

3. Results

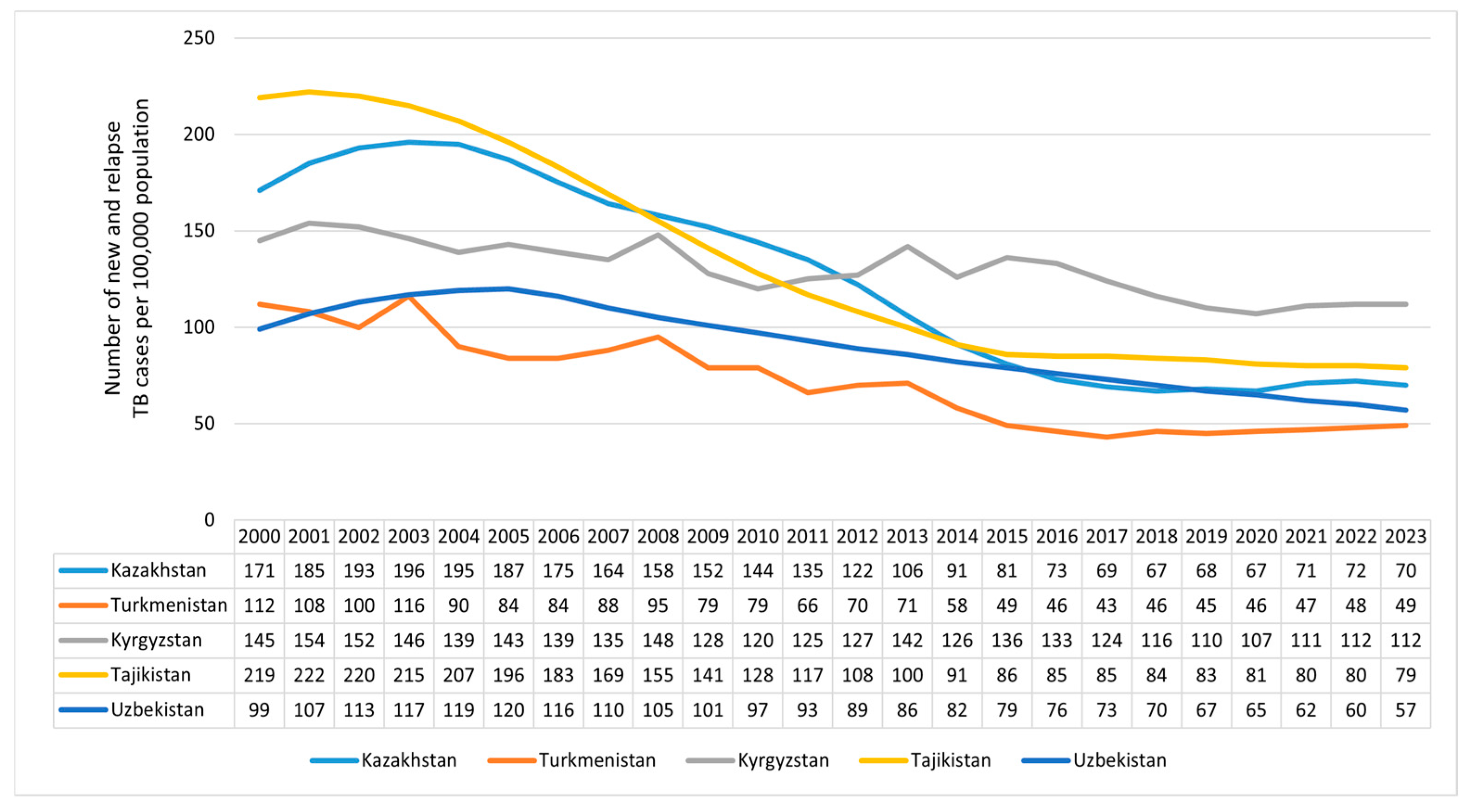

3.1. The Observed and Projected TB Incidence Rates in Central Asian Countries

3.2. SDHs of TB Incidence in Countries in Central Asia, 2000–2023

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Trends in TB Incidence in Central Asia and Beyond the Study Areas

4.2. Social Determinants of Health and TB Incidence

4.3. Implications for Public Health Policy

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 95% CI | 95% confidence interval |

| AAPC | Average annual percent change |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive integrated moving average |

| BCG | Bacillus Calmette–Guérin |

| CA | Central Asia |

| MTB | Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

| NAPs | National Action Plans |

| SDGs | United Nations Sustainable Development Goals |

| SDHs | Social determinants of health |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| WB | World Bank |

| WB DataBank | World Bank DataBank |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Furin, J.; Cox, H.; Pai, M. Tuberculosis. Lancet 2019, 393, 1642–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbewana Ntshanka, N.G.; Msagati, T.A.M. Trends and Progress on Antibiotic-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Genes in relation to Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2023, 2023, 6659212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguillón-Durán, G.P.; Prieto-Martínez, E.; Ayala, D.; García, J., Jr.; Thomas, J.M., 3rd; García, J.I.; Henry, B.M.; Torrelles, J.B.; Turner, J.; Ledezma-Campos, E.; et al. COVID-19 and chronic diabetes: The perfect storm for reactivation tuberculosis?: A case series. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021, 15, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The End TB Strategy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HTM-TB-2015.19 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336069/9789240013131-eng.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Kolahdooz, F.; Jang, S.L.; Deck, S.; Ilkiw, D.; Omoro, G.; Rautio, A.; Pirkola, S.; Møller, H.; Ferguson, G.; Evengård, B.; et al. A Scoping Review of the Current Knowledge of the Social Determinants of Health and Infectious Diseases (Specifically COVID-19, Tuberculosis, and H1N1 Influenza) in Canadian Arctic Indigenous Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Nguipdop-Djomo, P.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Smith, P.G.; Abubakar, I.; Mangtani, P. Drug misuse, tobacco smoking, alcohol and other social determinants of tuberculosis in UK-born adults in England: A community-based case-control study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ockenga, J.; Fuhse, K.; Chatterjee, S.; Malykh, R.; Rippin, H.; Pirlich, M.; Yedilbayev, A.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Barazzoni, R. Tuberculosis and malnutrition: The European perspective. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froeling, F.; Chen, J.; Meliefste, K.; Oldenwening, M.; Lenssen, E.; Vermeulen, R.; Gerlofs-Nijland, M.; van Triel, J.; Woutersen, A.; de Jonge, D.; et al. A co-created citizen science project on the short term effects of outdoor residential woodsmoke on the respiratory health of adults in the Netherlands. Environ. Health 2024, 23, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenova, Y.; Lim, L.; Salpynov, Z.; Gaipov, A.; Jakovljevic, M. Historical evolution of healthcare systems of post-soviet Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan: A scoping review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimakov, T.; Sadykova, L.; Kalmataeva, Z.; Kurakpaev, K.; Šmigelskas, K. Treatment of tuberculosis in South Kazakhstan: Clinical and economical aspects. Medicina 2013, 49, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakko, Y.; Madikenova, M.; Kim, A.; Syssoyev, D.; Mussina, K.; Gusmanov, A.; Zhakhina, G.; Yerdessov, S.; Semenova, Y.; Crape, B.L.; et al. Epidemiology of tuberculosis in Kazakhstan: Data from the Unified National Electronic Healthcare System 2014–2019. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e074208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilloeva, Z.; Aghabekyan, S.; Davtyan, K.; Goncharova, O.; Kabirov, O.; Pirmahmadzoda, B.; Rajabov, A.; Mirzoev, A.; Aslanyan, G. Tuberculosis in key populations in Tajikistan—A snapshot in 2017. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 2020, 14, 94S–100S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhoyarova, A.; Sargsyan, A.; Goncharova, O.; Kadyrov, A. Who is doing worse? Retrospective cross-sectional study of TB key population treatment outcomes in Kyrgyzstan (2015–2017). J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 2020, 14, 101S–108S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaev, K.; Parpieva, N.; Liverko, I.; Yuldashev, S.; Dumchev, K.; Gadoev, J.; Korotych, O.; Harries, A.D. Trends, Characteristics and Treatment Outcomes of Patients with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Uzbekistan: 2013–2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzon, D.; Zignol, M.; Bastard, M.; Floyd, K.; Kasaeva, T. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the global tuberculosis epidemic. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1234785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadu, A.; Hovhannesyan, A.; Ahmedov, S.; van der Werf, M.J.; Dara, M. Drug-resistant tuberculosis in eastern Europe and central Asia: A time-series analysis of routine surveillance data. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorokina, M.; Ukubayev, T.; Koichubekov, B. Tuberculosis incidence and its socioeconomic determi-nants: Developing a parsimonious model. Ann. Ig. 2023, 35, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhussupov, B.; Hermosilla, S.; Terlikbayeva, A.; Aifah, A.; Ma, X.; Zhumadilov, Z.; Abildayev, T.; Darisheva, M.; Berikkhanova, K. Risk Factors for Primary Pulmonary TB in Almaty Region, Kazakhstan: A Matched Case-Control Study. Iran. J. Public Health 2016, 45, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Bank Group. DataBank. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/home.aspx (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Tuberculosis Report 2024; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-programme-on-tuberculosis-and-lung-health/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tuberculosis (TB): TB Risk Factors; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/risk-factors/index.html (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Duarte, R.; Lönnroth, K.; Carvalho, C.; Lima, F.; Carvalho, A.C.C.; Muñoz-Torrico, M.; Centis, R. Tuberculosis, social determinants and co-morbidities (including HIV). Pulmonology 2018, 24, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darisheva, M.; Tracy, M.; Terlikbayeva, A.; Zhussupov, B.; Schluger, N.; McCrimmon, T. Knowledge and attitudes towards ambulatory treatment of tuberculosis in Kazakhstan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis Epidemiological Impact Analysis and Assessment of TB Surveillance System of Kazakhstan. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2019-3709-43468-61061 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Sharifov, R.; Nabirova, D.; Tilloeva, Z.; Zikriyarova, S.; Kishore, N.; Jafarov, N.; Yusufi, S.; Horth, R. TB treatment delays and associated risk factors in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 2019–2021. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evaluating Cost-Effective Investments to Reduce the Burden of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis (TB) in Kyrgyz Republic; Burnet Institute: Victoria, Australia, 2023; Available online: https://www.burnet.edu.au/our-work/reports-and-other-work/evaluating-cost-effective-investments-to-reduce-the-burden-of-drug-resistant-tuberculosis-tb-in-kyrgyz-republic (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Meshkov, I.; Petrenko, T.; Keiser, O.; Estill, J.; Revyakina, O.; Felker, I.; Raviglione, M.C.; Krasnov, V.; Schwartz, Y. Variations in tuberculosis prevalence, Russian Federation: A multivariate approach. Bull. World Health Organ. 2019, 97, 737–745A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Global Economy. Belarus: Tuberculosis Incidence. 2000–2022. Available online: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Belarus/Tuberculosis/ (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Skrahina, A.; Hurevich, H.; Zalutskaya, A.; Sahalchyk, E.; Astrauko, A.; Hoffner, S.; Rusovich, V.; Dadu, A.; de Colombani, P.; Dara, M.; et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Belarus: The size of the problem and associated risk factors. Bull. World Health Organ. 2013, 91, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokva, D.; Mori, H.; Valenti, S.; Remez, D.; Hadano, Y.; Naito, T. Analysis of the impact of crises tuberculosis incidence in Ukraine amid pandemics and war. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamnetiya, D.; Patel, P.; Jha, R.P.; Shri, N.; Singh, M.; Bhattacharyya, K. Trends in incidence and mortality of tuberculosis in India over past three decades: A joinpoint and age-period-cohort analysis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Ahmed, H.; Salman, A.; Iqbal, R.; Hussaini, S.J.; Malikzai, A. The rising tide of tuberculosis in Pakistan: Factors, impact, and multi-faceted approaches for prevention and control. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e70130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansang, M.A.D.; Alejandria, M.M.; Law, I.; Juban, N.R.; Amarillo, M.L.E.; Sison, O.T.; Cruz, J.R.B.; Ang, C.F.; Buensalido, J.A.L.; Cañal, J.P.A.; et al. High TB burden and low notification rates in the Philippines: The 2016 national TB prevalence survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyew, A.M.; Clements, A.C.A.; Akalu, T.Y.; Gilmour, B.; Alene, K.A. Ecological-level factors associated with tuberculosis incidence and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0003425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Fan, P.; John, R.; Chen, J. Urbanization on the Mongolian Plateau after economic reform: Changes and causes. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 86, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, A.; Nelson, A.; McMenomy, T. Global mapping of urban-rural catchment areas reveals unequal access to services. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2011990118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, P.J.; Yuen, C.M.; Sismanidis, C.; Seddon, J.A.; Jenkins, H.E. The global burden of tuberculosis mortality in children: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, e898–e906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Extensive Review of Tuberculosis Prevention, Control and Care in Kazakhstan, 10–16 May 2012; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/131834 (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Lönnroth, K.; Jaramillo, E.; Williams, B.G.; Dye, C.; Raviglione, M. Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: The role of risk factors and social determinants. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 2240–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siroka, A.; Ponce, N.A.; Lönnroth, K. Association between spending on social protection and tuberculosis burden: A global analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, A.; Basu, S.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D.; Sandgren, A.; Semenza, J. Social protection and tuberculosis control in 21 European countries, 1995–2012: A cross-national statistical modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 1105–1112, Erratum in Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 475. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30202-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.H.; Murray, M.; Cohen, T.; Colijn, C.; Ezzati, M. Effects of smoking and solid-fuel use on COPD, lung cancer, and tuberculosis in China: A time-based, multiple risk factor, modelling study. Lancet 2008, 372, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). SDG7 Roadmap for Kazakhstan; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2025-04/SDG7%20Roadmap%20for%20Kazakhstan_FinalSigned.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Yang, D.M.; Cao, L.Q.; Liu, J.Y.; Tao, N.N.; Li, Y.F.; Liu, Y.; Song, W.M.; Xu, T.T.; Li, S.J.; et al. Association between economic development level and tuberculosis registered incidence in Shandong, China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.B.; Gupta, R.; Atreja, A.; Verma, M.; Vishvkarma, S. Tuberculosis and nutrition. Lung India 2009, 26, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Saravanan, N.; Bethunaickan, R.; Tripathy, S. Malnutrition: Modulator of Immune Responses in Tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaw, Y.; Getaneh, Z.; Melku, M. Anemia as a risk factor for tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2021, 26, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Yuan, S.Y.; Li, Q.G.; Li, J.X.; Yin, X.Y.; Liu, N.N. Prevalence and risk factors of malnutrition in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1173619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glushkova, N.; Semenova, Y.; Sarria-Santamera, A. Editorial: Public health challenges in post-Soviet countries during and beyond COVID-19. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1290910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagger, P.; McCord, R.; Gallerani, A.; Hoffman, I.; Jumbe, C.; Pedit, J.; Phiri, S.; Krysiak, R.; Maleta, K. Household air pollution exposure and risk of tuberculosis: A case-control study of women in Lilongwe, Malawi. BMJ Public Health 2024, 2, e000176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obore, N.; Kawuki, J.; Guan, J.; Papabathini, S.S.; Wang, L. Association between indoor air pollution, tobacco smoke and tuberculosis: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health 2020, 187, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, S.K.; Tong, Z.W.; Ren, F.; Hu, C.M.; Su, S.F.; Kan, X.H.; Cao, H.; Li, R.; et al. Nutritional status in patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis and new nutritional risk screening model for active tuberculosis: A national, multicenter, cross-sectional study in China. J. Thorac. Dis. 2023, 15, 2779–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cegielski, J.P.; McMurray, D.N. The relationship between malnutrition and tuberculosis: Evidence from studies in humans and experimental animals. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2004, 8, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2023; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240083851 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

| Year | Country | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kazakhstan | Kyrgyzstan | Tajikistan | Turkmenistan | Uzbekistan | |

| 2024 | 66 | 108 | 77 | 42 | 54 |

| 2025 | 62 | 106 | 75 | 39 | 50 |

| 2026 | 58 | 105 | 72 | 35 | 45 |

| 2027 | 53 | 103 | 69 | 32 | 40 |

| 2028 | 48 | 101 | 66 | 29 | 35 |

| 2029 | 43 | 99 | 63 | 26 | 29 |

| 2030 | 38 | 98 | 60 | 23 | 22 |

| Model parameters | ARIMA (1.2.0) p = 0.015 + | Holt p = 0.487 | ARIMA (0.3.0) p = 0.623 | Holt p = 0.020 + | ARIMA (0.2.0) p = 0.126 |

| Predictors | Model 1 (Enter Method) | Model 2 (Backward Method) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Coefficients (95% CI (Lower; Upper)) | p- Value | Standardized Coefficients (95% CI (Lower; Upper)) | p- Value | |

| Access to clean fuels and technologies for cooking | −0.644 (−16.779; −5.725) | <0.001 ° | −0.777 (−16.222; −10.922) | <0.001 ° |

| Life expectancy at birth, total | −0.103 (−4.541; 1.660) | 0.328 | - | - |

| Population ages 0–14 | −0.638 (−24.859; −11.706) | <0.001 ° | −0.733 (−24.338; −17.639) | <0.001 ° |

| Population density | 0.298 (3.356; 52.930) | 0.028 * | 0.386 (18.961; 54.039) | <0.001 ° |

| Prevalence of undernourishment | 0.098 (0.042; 5.314) | 0.047 * | 0.085 (−0.199; 4.837) | 0.069 |

| Model parameters | R2 = 0.991; overall model p < 0.001 ° | R2 = 0.991; overall model p = 0.328 | ||

| Predictors | Model 1 (Enter Method) | Model 2 (Backward Method) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Coefficients (95% CI (Lower; Upper)) | p- Value | Standardized Coefficients (95% CI (Lower; Upper)) | p- Value | |

| Life expectancy at birth, total | −0.213 (−8.234; 4.268) | 0.517 | - | - |

| Prevalence of anemia among nonpregnant women | 0.652 (−0.169; 12.055) | 0.056 | 0.851 (5.639; 9.877) | <0.001 ° |

| Model parameters | R2 = 0.729; overall model p < 0.001 ° | R2 = 0.724; overall model p = 0.517 | ||

| Predictors | Model 1 (Enter Method) | Model 2 (Backward Method) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Coefficients (95% CI (Lower; Upper)) | p- Value | Standardized Coefficients (95% CI (Lower; Upper)) | p- Value | |

| GDP per capita | −0.470 (−0.102; −0.060) | <0.001 ° | −0.476 (−0.101; −0.062) | <0.001 ° |

| Immunization, measles | −0.016 (−1.211; 0.872) | 0.737 | - | - |

| Population density | −0.177 (−2.126; −1.710) | 0.032 * | −0.179 (−2.108; −0.147) | 0.026 * |

| Prevalence of anemia among nonpregnant women | 0.209 (3.633; 16.702) | 0.004 ** | 0.212 (3.988; 16.606) | 0.003 ** |

| Prevalence of undernourishment | 0.189 (0.137; 1.710) | 0.024 * | 0.194 (0.194; 1.699) | 0.016 * |

| Model parameters | R2 = 0.987; overall model p < 0.001 ° | R2 = 0.999; overall model p = 0.737 | ||

| Predictors | Model 1 (Enter Method) | Model 2 (Backward Method) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Coefficients (95% CI (Lower; Upper)) | p- Value | Standardized Coefficients (95% CI (Lower; Upper)) | p- Value | |

| Physicians | −0.938 (−205.939; −14.868) | 0.026 * | −0.930 (−202.027; −16.911) | 0.023 * |

| Prevalence of anemia among nonpregnant women | 1.732 (6.239; 22.358) | 0.001 ** | 1.784 (8.239; 21.227) | <0.001 ° |

| Total greenhouse gas emissions including LULUCF | 0.442 (−0.025; 1.732) | 0.056 | - | - |

| Model parameters | R2 = 0.977; overall model p < 0.001 ° | R2 = 0.973; overall model p = 0.843 | ||

| Predictors | Model 1 (Enter Method) | Model 2 (Backward method) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Coefficients (95% CI (Lower; Upper)) | p- Value | Standardized Coefficients (95% CI (Lower; Upper)) | p- Value | |

| Current health expenditure per capita | −0.110 (−0.278; 0.178) | 0.652 | - | - |

| GDP per capita | −0.219 (−0.02; 0.01) | 0.503 | - | - |

| Life expectancy at birth, total | −0.590 (−10.342; −0.680) | 0.027 * | −0.883 (−10.178;−6.303) | <0.001 ° |

| Model parameters | R2 = 0.798; overall model p < 0.001 ° | R2 = 0.780; overall model p = 0.213 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kussainova, A.; Kassym, L.; Kussainov, A.; Orazalina, A.; Smail, Y.; Derbissalina, G.; Bekbergenova, Z.; Kozhakhmetova, U.; Aitenova, E.; Semenova, Y. Impact of Social Determinants of Health on the Incidence of Tuberculosis in Central Asia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010068

Kussainova A, Kassym L, Kussainov A, Orazalina A, Smail Y, Derbissalina G, Bekbergenova Z, Kozhakhmetova U, Aitenova E, Semenova Y. Impact of Social Determinants of Health on the Incidence of Tuberculosis in Central Asia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010068

Chicago/Turabian StyleKussainova, Assiya, Laura Kassym, Almas Kussainov, Ainash Orazalina, Yerbol Smail, Gulmira Derbissalina, Zhanagul Bekbergenova, Ulzhan Kozhakhmetova, Elvira Aitenova, and Yuliya Semenova. 2026. "Impact of Social Determinants of Health on the Incidence of Tuberculosis in Central Asia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010068

APA StyleKussainova, A., Kassym, L., Kussainov, A., Orazalina, A., Smail, Y., Derbissalina, G., Bekbergenova, Z., Kozhakhmetova, U., Aitenova, E., & Semenova, Y. (2026). Impact of Social Determinants of Health on the Incidence of Tuberculosis in Central Asia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010068