Statewide Assessment of Public Park Accessibility and Usability and Playground Safety

Highlights

- Statewide evaluation of accessibility, usability, and safety in public parks with playgrounds as community settings for physical activity;

- Focus on disability-inclusive access to public environments that influence physical activity, social participation, and equitable health opportunities.

- Identifies structural and environmental gaps, such as transit, crossings, curb ramps, restrooms, trails, and play features, that restrict safe, independent use of parks and playgrounds for people with disabilities;

- Demonstrates how park and playground accessibility and safety conditions may shape disparities in physical activity and community engagement.

- Identifies actionable priorities for improving transit access, pedestrian infrastructure, amenities, inclusive play design, and communication support;

- Provides evidence to guide equitable reinvestment and integration of disability inclusion in planning, transportation, and parks and recreation policy and practice.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the patterns of park accessibility and usability, and playground accessibility and safety, across public, non–fee-based parks with playgrounds in Delaware?

- (2)

- Do park accessibility and usability, and playground accessibility and safety indicators vary by county and urbanicity category?

- (3)

- What relationships exist between playground accessibility and life-threatening safety risks?

2. Materials and Methods

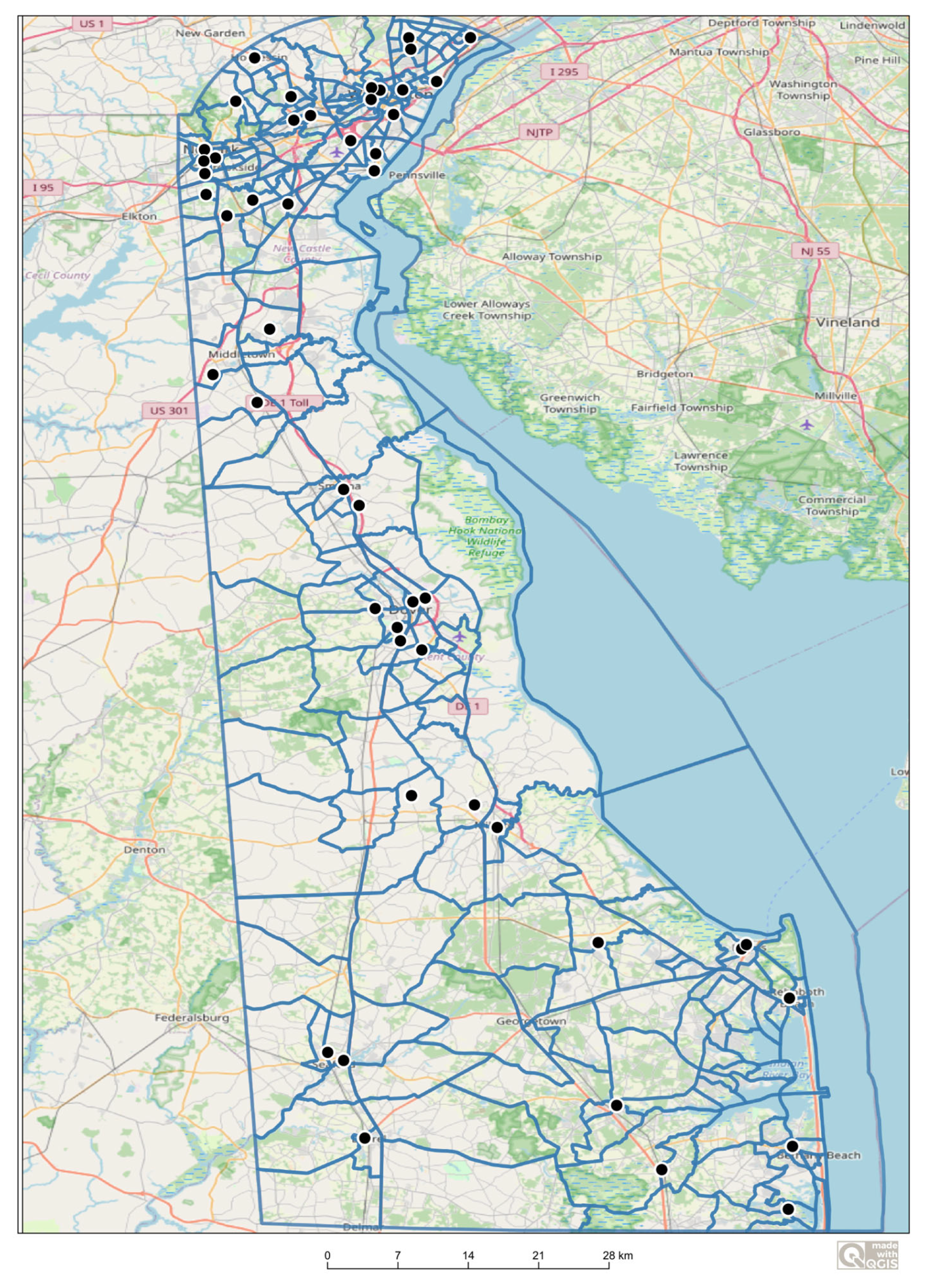

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Community and Demographic Context

3.2. Transit Stops and Arrival Access

3.3. Crosswalks and Intersections

3.4. Curb Ramps and Transitions

3.5. Park Entry and Parking

3.6. Pathways and Environmental Features

3.7. Restrooms

3.8. Physical Activity Areas, Playgrounds, and Multi-Use Trails

3.9. Playground Accessibility and Safety

3.10. Promotional Materials

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic Context

4.2. Foundational Accessibility

4.3. Amenities, Usability, and Safety

4.4. Communication and Wayfinding

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

4.6. Implications for Research and Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADA | Americans with Disabilities Act |

| ADAAG | Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines |

| APS | Accessible pedestrian signals |

| CHII | Community Health Inclusion Index |

| ICF | International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health |

| KC | Kent County |

| NCC | New Castle County |

| PROWAG | Public Rights-of-Way Accessibility Guidelines |

| RUCA | Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes |

| S.A.F.E.™ | Supervision, Age-appropriate design, Fall surfacing, Equipment maintenance |

| SC | Sussex County |

Appendix A

| ID | Park Name (Inaugural Year) | County | Size (Acres) | Physical Activity-Related Amenities | Address |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kings Croft Park (1994) | NCC | 7.5 | Baseball/Softball Field, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Trails/Paths | 1 Regal Blvd, Bear, DE 19701 |

| 2 | Glasgow Regional Park (NR; 2016 for H!gh 5 Sensory PG) | NCC | 250 | Basketball Courts, H!gh 5 Sensory PG †, PG, Tennis Courts, Trails/Paths | 2275 Pulaski Hwy, Newark, DE 19702 |

| 3 | Iron Hill Park (1968) | NCC | 335 | Disc Golf Course, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Trails/Paths | 1337 S Old Baltimore Pike, Newark, DE 19702 |

| 4 | Becks Pond Park (NR) | NCC | 28 | PG | 793 Salem Church Road, Newark, DE 19702 |

| 5 | Woods Haven Kruse Park (NR) | NCC | 44.9 | Multipurpose Fields, PG, Trails/Paths | 100 Darley Rd, Claymont, DE 19703 |

| 6 | Swift Memorial Park (1976) | NCC | 30 | Baseball Field, PG, Soccer Field, Trails/Paths | 1001 Valley Rd Hockessin, DE 19707 |

| 7 | Charles Price Memorial Park (2007) | NCC | 100 | Multipurpose Fields, PG, Trails/Paths | 955 Levels Rd, Middletown, DE 19709 |

| 8 | NCC Southern Park (2023) | NCC | 100 | Baseball/Softball Field, Basketball Courts, Fitness Equipment, Gaga Pit, Multipurpose Fields, Pickleball Courts, PG, Recreation Programs, Tennis Courts, Trails/Paths, Zipline | 1276 Shallcross Lake Rd, Middletown, DE 19709 |

| 9 | Kells Park (NR) | NCC | 5.2 | Baseball/Softball Field, Basketball Courts, PG, Soccer Field, Tennis Practice Wall, Trails/Paths | 201 Kells Ave, Newark, DE 19711 |

| 10 | Paper Mill Park (2008) | NCC | 29.3 | Basketball Courts, PG, Soccer Field, Tennis Courts, Trails/Paths | 1050 Paper Mill Rd, Newark, DE 19711 |

| 11 | Phillips Park (1974) | NCC | 13.7 | Basketball Courts, PG, Skate Park, Tennis Courts, Trails/Paths | 101 B Street, Newark DE 19711 |

| 12 | Hillside Park (2021) | NCC | 7 | Natural Play Area, PG, Trails/Paths | 151 Forest Lane, Newark, DE 19711 |

| 13 | Rittenhouse Park (1974) | NCC | 45.9 | PG, Trails/Paths | 228 W Chestnut Hill Rd, Newark, DE 19713 |

| 14 | Chelsea Manor Park (2005) | NCC | 10.6 | Baseball/Softball Field, PG, Soccer Field, Trails/Paths | 0 West Roosevelt Avenue, New Castle DE 19720 |

| 15 | New Castle Battery Park (NR, 2023 for PG) | NCC | 17.9 | PG, Trails/Paths | 1 Delaware St, New Castle, DE 19720 |

| 16 | Rogers Manor Park (NR) | NCC | 8.5 | Baseball/Softball Field, Basketball Court, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Soccer Field, Tennis Court | 441 Moores Lane, New Castle DE, 19720 |

| 17 | Townsend Municipal Park (2006) | NCC | 11.5 | Basketball Court, Fitness Equipment, Pickleball Court, PG, Skatepark, Trails/Paths | 0 Edgar Rd, Townsend, DE 19734 |

| 18 | Eden Park (1890) | NCC | 13.43 | Basketball Courts, Football Fields, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Swimming Pools | 900 New Castle Ave, Wilmington, DE 19801 |

| 19 | Brown Burton Winchester Park (1917) | NCC | 55.06 | Baseball Fields, Basketball Courts, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Swimming Pools | 2313 N Locust Street, Wilmington, DE 19802 |

| 20 | Talley Day Park (1970) | NCC | 37 | Baseball/Softball Field, Basketball Court, Delaware Greenways, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Soccer Field, Tennis Court, Trails/Paths | 1308 Foulk Rd, Wilmington DE 19803 |

| 21 | Powell Ford Park (NR) | NCC | 200 | Baseball/Softball Field, PG | 1000 Kiamensi Rd, Wilmington, DE 19804 |

| 22 | Kosciuszko Park (1886) | NCC | 7.08 | Basketball Courts, PG, Tennis Courts | 1320 Beech Street, Wilmington, DE 19805 |

| 23 | Father Tucker Memorial Park (1910) | NCC | 3.68 | Baseball Fields, PG | 1800 W 10th Street, Wilmington, DE 19805 |

| 24 | Cool Springs Park (1862) | NCC | 14.7 | Fitness Equipment, Multipurpose Space, PG, Trails/Paths | 1001 N Van Buren St, Wilmington, DE 19806 |

| 25 | Delcastle Recreational Park (1974) | NCC | 400 | Baseball/Softball Field, Basketball Court, Fitness Equipment, Football Field, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Soccer Field, Street Hockey, Tennis Court, Trails/Paths | 2920 Duncan Rd, Wilmington, DE 19808 |

| 26 | NCC Delpark Manor Park (NR) | NCC | 7 | Baseball/Softball Field, Basketball Court, PG, Trails/Paths | 2010 St James Church Rd, Wilmington, DE 19808 |

| 27 | River Road Park (NR) | NCC | 8.5 | Baseball/Softball Field, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Soccer Field | 610 River Rd, Wilmington, DE 19809 |

| 28 | Bonsall Park (NR) | NCC | 17.8 | Baseball/Softball Field, Basketball Court, PG, Soccer Field, Tennis Courts, Trails/Paths | 3000 Silverside Rd, Wilmington, DE 19810 |

| 29 | Tidbury Creek County Park (NR) | KC | 30 | Multipurpose Fields, PG, Softball Fields, Trails/Paths | 2233 S State St, Dover, DE 19901 |

| 30 | Dover Park (1974) | KC | 28.2 | Basketball Courts, Disc Golf Courses, PG, Pickleball Courts, Shuffleboard Courts, Softball Field, Tennis Courts, Trails/Paths | 1210 White Oak Rd, Dover, DE 19901 |

| 31 | Silver Lake Park (1917) | KC | 182 | Fitness Equipment, PG, Trails/Paths | 300 Washington St Dover, DE 19901 |

| 32 | Mallard Pond Park (2014) | KC | 6.07 | PG, Trails/Paths | 45 Marsh Creek Ln, Dover, DE 19904 |

| 33 | Brecknock County Park (1996) | KC | 86 | Baseball/Softball Fields, Fitness Equipment, Football Field, Horseshoes Pits, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Sand Volleyball Courts, Sports Pavilion, Trails/Paths, Youth Activity Center | 80 Old Camden Rd, Camden, DE 19934 |

| 34 | Browns Branch County Park (2006) | KC | 78 | Baseball/Softball Fields, Fitness Equipment, Horseshoes Pits, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Sand Volleyball Courts, Soccer Field, Trails/Paths | 1415 Killens Pond Rd, Harrington, DE 19952 |

| 35 | Tony Silicato Memorial Park & Can-Do PG (2006) | KC | 31 | Disk Golf Course, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Soccer Fields, Trails/Paths | 101 Delaware Veterans Blvd, Milford, DE 19963 |

| 36 | Big Oak County Park (2003) | KC | 90 | Baseball/Softball Fields, Fitness Equipment, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Rock Climbing Wall, Sports Pavilion, Trails/Paths, Youth Activity Center | 417 Big Oak Rd, Smyrna, DE 19977 |

| 37 | Lake Como Recreation Area (1956) | KC | 35 | PG, Swimming Beach Area | 420 S Dupont Blvd, Smyrna, DE 19977 |

| 38 | Schutte Park (2001) | KC | 71 | Baseball/Softball Fields, John W. Pitts Recreation Center, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Trails/Paths | 10 Electric Ave, Dover, DE, 19904 |

| 39 | Frankford Community Park (2012) | SC | 33 | Basketball Court, Fitness Equipment, Multipurpose Field, PG, Soccer Practice Goals, Trails/Paths, Volleyball Court, | 30 Clayton Ave, Frankford, DE 19945 |

| 40 | John West Park (NR) | SC | 4.5 | Fitness Equipment, PG, Trails/Paths | 32 West Ave, Ocean View, DE 19970 |

| 41 | Roger C. Fisher Laurel River Park (2001) | SC | 2.8 | Canoeing, Fishing, Kayaking, Motorized Boating, Exercise Circuit, PG | W 6th St, Laurel, DE 19956 |

| 42 | Lewes CanalFront Park (2009) | SC | 14.6 | Baseball/Softball Fields, Canoeing, Kayaking, Fishing, Multipurpose Field, Pickleball Court, PG, Softball Field, Tennis Court | 211 Front St, Lewes, DE 19958 |

| 43 | George H.P. Smith Park (NR) | SC | 15.1 | Fishing, Horseshoe Pit, Multipurpose Fields, PG, Trails/Paths | Dupont Ave, Lewes, DE 19958 |

| 44 | Cupola Park (1976) | SC | 10 | Canoeing, Kayaking, | end of Morris St, Millsboro, DE 19966 |

| 45 | Milton Memorial Park (1939) | SC | 4 | Canoeing, Kayaking, Fishing, PG, Trails/Paths | 113 Union St, Milton, DE 19968 |

| 46 | The Grove Park (1963) | SC | 2.4 | Canoeing, Kayaking, Fitness Circuit, PG, Shuffleboard Courts, Trails/Paths | 3 Grove St, Rehoboth Beach, DE 19971 |

| 47 | Soroptimist Park/ Walking Trail (2001) | SC | 2.8 | PG, Trails/Paths | 1100 Middleford Rd, Seaford, DE 19973 |

| 48 | Marvel Square Park (NR) | SC | NR | Grassy area, open space, pavilion (optional), PG | 207 Franklin St, Milford, DE 19963 |

| 49 | Jay’s Nest & Sports Complex (2002) | SC | 26 | Baseball/Softball Fields, Football Fields, Horseshoe Pits, Multipurpose Field, PG, Soccer Fields, Trails/Paths | 490 N Market St Ext, Seaford, DE 19973 |

| 50 | Swann Keys Park | SC | PG; Mini-golf; Basketball; Multi-purpose courts (Pickleball/Tennis); Volleyball; Pool & kids’ splash zone; Shuffleboard; Picnic pavilion; Horseshoe pits | 37689 Swann Dr, Selbyville, DE 19975 |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey data, 2022. In Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates, Table DP05. Available online: https://data.census.gov (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Krahn, G.L.; Walker, D.K.; Correa-De-Araujo, R. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, S198–S206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhasz, A.C.; Byers, R. Prevalence of chronic health conditions among people with disabilities in the United States. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 106, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimmer, J.H.; Vanderbom, K.A. A call to action: Building a translational inclusion team science in physical activity, nutrition, and obesity management for children with disabilities. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, D.D.; Courtney-Long, E.A.; Stevens, A.C.; Sloan, M.L.; Lullo, C.; Visser, S.N.; Fox, M.H.; Armour, B.S.; Campbell, V.A.; Brown, D.R. Vital signs: Disability and physical activity—United States, 2009–2012. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014, 63, 407–413. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd ed.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, M.A.; Devan, H.; Fitzgerald, H.; Han, K.; Liu, L.T.; Rouse, J. Accessibility and usability of parks and playgrounds. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Justice. 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design. Available online: https://www.ada.gov/regs2010/2010ADAStandards/2010ADAstandards.htm (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Eisenberg, Y.; Rimmer, J.H.; Mehta, T.; Fox, M.H. Development of a community health inclusion index: An evaluation tool for improving inclusion of people with disabilities in community health initiatives. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 as Amended; 42 U.S.C. § 12101 et seq; U.S. Government: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- U.S. Access Board. Accessibility guidelines for pedestrian facilities in the public right-of-way. Fed. Regist. 2023, 88, 53604–53685. [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld, E.; Maisel, J. Universal Design: Creating Inclusive Environments; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Saitta, M.; Devan, H.; Boland, P.; Perry, M.A. Park-based physical activity interventions for persons with disabilities: A mixed-methods systematic review. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnowska-Heciak, M.; Suchocka, M.; Błaszczyk, M.; Muszyńska, M. Urban parks as perceived by city residents with mobility difficulties: A qualitative study with in-depth interviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoglavec, K.; Papeš, O.; Lovrić, V.; Raspudić, A.; Nevečerel, H. Accessibility of urban forests and parks for people with disabilities in wheelchairs, considering the surface and longitudinal slope of the trails. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Yadav, M.; Nayak, B.K. A systematic literature review on inclusive public open spaces: Accessibility standards and universal design principles. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.E.; Moore, A.; Lynch, H. Inclusive play space design for users with neuro-physical disabilities: Adult, youth, and child perspectives in Ireland. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2025, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.; Boyle, B.; Lynch, H. Designing for inclusion in public playgrounds: A scoping review of definitions, and utilization of universal design. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2023, 18, 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suminski, R.; Presley, T.; Wasserman, J.A.; Mayfield, C.A.; McClain, E.; Johnson, M. Playground safety is associated with playground, park, and neighborhood characteristics. J. Phys. Act. Health 2015, 12, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firkin, C.J.; Rechner, L.; Obrusnikova, I. Paving the way to active living for people with disabilities: Evaluating park and playground accessibility and usability in Delaware. Del. J. Public Health 2024, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. Rural–Urban Commuting Area Codes. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- WWAMI Rural Health Research Center. Rural–Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) Codes. Available online: https://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-data.php (accessed on 6 June 2024).

- Hart, L.G.; Larson, E.H.; Lishner, D.M. Rural definitions for health policy and research. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 1149–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Program for Playground Safety. Rate Your Playground. University of Northern Iowa. Available online: https://playgroundsafety.uni.edu/take-action/rate-your-playground (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Tomczak, M.; Tomczak, E. The need to report effect size estimates revisited. An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. Trends Sport Sci. 2014, 21, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Income in the Past 12 Months (in 2024 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars). American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates Subject Tables. Table S1901. Available online: https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2024.S1901 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- U.S. Census Bureau. Poverty Status in the Past 12 Months, American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. Table S1701. Available online: https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2024.S1701 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Cohen, D.A.; Han, B.; Nagel, C.J.; Harnik, P.; McKenzie, T.L.; Evenson, K.R.; Marsh, T.; Williamson, S.; Vaughan, C.; Katta, S. The first national study of neighborhood parks: Implications for physical activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.; Hosking, J.; Woodward, A.; Witten, K.; MacMillan, A.; Field, A.; Baas, P.; Mackie, H. Systematic literature review of built environment effects on physical activity and active transport—An update and new findings on health equity. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; World Health Organization Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, D.E.; Huang, D.L.; Simonovich, S.D.; Belza, B. Outdoor built environment barriers and facilitators to activity among midlife and older adults with mobility disabilities. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remillard, E.T.; Campbell, M.L.; Koon, L.M.; Rogers, W.A. Transportation challenges for persons aging with mobility disability: Qualitative insights and policy implications. Disabil. Health J. 2022, 15, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Highway Administration. Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways, 11th ed.; U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Transportation. Accessible Pedestrian Signals: Program Status Report. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/pdf/2021-aps-program-status-report.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Kärmeniemi, M.; Lankila, T.; Ikäheimo, T.; Koivumaa-Honkanen, H.; Korpelainen, R. The built environment as a determinant of physical activity: A systematic review of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 52, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, A.T.; Wende, M.; Hughey, M.; Stowe, E.; Schipperijn, J.; Hipp, A.; Javad Koohsari, M. Association of composite park quality with park use in four diverse cities. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 35, 102381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Recreation and Park Association. 2025 NRPA Agency Performance Review; National Recreation and Park Association: Ashburn, VA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Timke, E. The advertising industry’s advice on accessibility and disability representation: A critical discourse analysis. J. Advert. 2023, 52, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viglia, G.; Tsai, W.-H.S.; Das, G.; Pentina, I. Inclusive advertising for a better world. J. Advert. 2023, 52, 643–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrie, R. Universalism, universal design and equitable access to the built environment. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-Y.; de Lannoy, L.; Kim, Y.-B.; Rathod, A.; James, M.E.; Lopes, O.; Nasrallah, B.; Thankarajah, A.; Adjei-Boadi, D.; Amando de Barros, M.I.; et al. 2025 Position statement on active outdoor play. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2025, 22, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population Characteristic | Delaware (n = 50) | NCC (n = 28) | KC (n = 10) | SC (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population, N (% with disability) | 1,037,354 ± 1568 (14.0 ± 0.8) | 580,531 ± 655 (12.5 ± 1.1) | 188,555 ± 1199 (16.8 ± 2.0) | 268,268 ± 549 (15.2 ± 1.4) |

| Median Age (years) | 41.5 ± 0.1 | 38.5 ± 0.4 | 39.2 ± 0.2 | 51.4 ± 0.2 |

| Disability by Age Group, N (years) | ||||

| Under 5 years | 545 ± 445 | 506 ± 433 | 0 ± 208 | 39 ± 59 |

| 5 to 17 years | 9766 ± 2480 | 4503 ± 1485 | 1645 ± 792 | 3618 ± 1655 |

| 18 to 34 years | 19,924 ± 2974 | 11,605 ± 2244 | 4537 ± 1369 | 3782 ± 1655 |

| 35 to 64 years | 46,886 ± 4256 | 24,208 ± 3540 | 11,758 ± 2182 | 10,920 ± 1967 |

| 65 to 74 years | 29,875 ± 3161 | 13,117 ± 2209 | 6864 ± 1356 | 9894 ± 1422 |

| 75+ years | 38,130 ± 2175 | 18,807 ± 1372 | 6858 ± 996 | 12,465 ± 1325 |

| Sex, N (% with disability) | ||||

| Female | 540,395 ± 1595 (14.1 ± 0.9) | 300,177 ± 897 (13.0 ± 1.2) | 99,642 ± 565 (16.7 ± 2.4) | 140,576 ± 1201 (14.6 ± 1.7) |

| Male | 496,959 ± 1927 (13.9 ± 1.0) | 280,354 ± 576 (12.0 ± 1.4) | 88,913 ± 1206 (16.9 ± 2.4) | 127,692 ± 1459 (15.9 ± 1.8) |

| Race/Ethnicity, N (% with disability) | ||||

| Asian alone a | 50,727 ± 1570 (7.0 ± 1.8) | 40,467 ± 1472 (5.8 ± 1.7) | 5931 ± 400 (14.8 ± 9.0) | 4329 ± 261 (7.2 ± 7.7) |

| Black/African American alone a | 226,593 ± 6735 (13.6 ± 1.9) | 153,206 ± 3960 (12.9 ± 2.4) | 47,788 ± 3723 (16.2 ± 4.5) | 25,599 ± 3230 (13.0 ± 4.1) |

| White alone a | 604,435 ± 6203 (15.0 ± 0.7) | 299,438 ± 4514 (13.5 ± 1.1) | 105,771 ± 1845 (18.0 ± 2.3) | 199,226 ± 3336 (15.6 ± 1.5) |

| Two or More Races | 94,094 ± 7943 (12.7 ± 2.5) | 51,368 ± 6424 (11.8 ± 3.0) | 22,315 ± 4216 (15.1 ± 5.5) | 20,411 ± 4345 (12.5 ± 4.7) |

| Hispanic/Latino (any race) | 121,353 ± 734 (9.7 ± 2.4) | 72,884 ± 436 (10.1 ± 3.1) | 15,798 ± 544 (5.7 ± 2.8) | 32,671 ± 118 (11.0 ± 5.1) |

| Household Income & Poverty | ||||

| Median (USD) | 82,855 ± 1234 | 89,901 ± 1993 | 72,872 ± 1932 | 78,162 ± 1865 |

| Mean (USD) | 109,519 ± 1313 | 118,003 ± 1977 | 89,176 ± 2271 | 105,000 ± 2259 |

| % Below Poverty | 10.7 ± 0.5 | 10.2 ± 0.5 | 11.3 ± 1.0 | 11.5 ± 1.0 |

| Accessibility Feature | Delaware (n = 50) | NCC (n = 28) | KC (n = 10) | SC (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transit stops near the site entrance | 15 (30.0) | 11 (39.3) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| Shelter at the transit stop | 3 (6.0) | 3 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Seating at the transit stop | 6 (12.0) | 3 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| TTY signage at the transit stop | 7 (14.0) | 5 (17.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) |

| Space for mobility device maneuvering (≥5 ft) | 9 (18.0) | 7 (25.0) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (8.3) |

| Stable, firm landing surface at transit stop | 11 (22.0) | 7 (25.0) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| Lighting at or near the transit stop | 10 (20.0) | 7 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| Accessibility Feature | Delaware (n = 50) | NCC (n = 28) | KC (n = 10) | SC (n = 12) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Many | Some | Any Presence * | |||

| Crosswalk marked with stripes/paint/bricks | 11 (22.0) | 7 (14.0) | 7 (14.0) | 15 (53.6) | 5 (50.0) | 5 (41.7) |

| Crossing free of obstacles/hazards | 22 (44.0) | 13 (26.0) | 5 (10.0) | 24 (85.7) | 7 (70.0) | 9 (75.0) |

| Curb ramps at both ends of the crossing | 25 (50.0) | 7 (14.0) | 3 (6.0) | 22 (78.6) | 4 (40.0) | 9 (75.0) |

| Auditory crossing signals near the site | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Visual countdown timers at traffic signals near the site | 2 (4.0) | 2 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Traffic signal crossing time accommodates slow-paced walking/rolling | 2 (4.0) | 2 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Accessibility Feature | Delaware (n = 50) | NCC (n = 28) | KC (n = 10) | SC (n = 12) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curb ramps are needed on the approach route (Yes) | 41 (82.0) | 25 (89.3) | 5 (50.0) | 11 (91.7) | ||

| Among sites where curb ramps were needed: | ||||||

| Accessibility Feature | All a | Many a | Some a | Any presence *,a | ||

| (n = 41) | (n = 41) | (n = 41) | (n = 25) | (n = 5) | (n = 11) | |

| Curb-ramp slope is <8.3% | 27 (65.9) | 5 (12.2) | 2 (4.9) | 19 (76.0) | 5 (100) | 10 (90.9) |

| Curb ramps free of barriers or hazards | 25 (61.0) | 11 (26.8) | 3 (7.3) | 23 (92.0) | 5 (100) | 11 (100) |

| Curb-ramp surface free of breaks | 29 (70.7) | 2 (4.9) | 4 (9.8) | 19 (76.0) | 5 (100) | 11 (100) |

| Detectable warning surface in good condition | 11 (26.8) | 5 (12.2) | 7 (17.1) | 11 (44.0) | 4 (80.0) | 8 (72.7) |

| No curb ramps present | 5 (12.2) | 5 (12.2) | 15 (36.6) | 18 (72.0) | 3 (60.0) | 4 (36.4) |

| Accessibility Feature | Delaware (n = 50) | NCC (n = 28) | KC (n = 10) | SC (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parking lot available at the park | 44 (88.0) | 23 (82.1) | 9 (90.0) | 12 (100) |

| Accessible spaces designated with the International Symbol of Accessibility on an upright sign in the lot (min. 60″) | 32 (64.0) | 16 (57.1) | 7 (70.0) | 9 (75.0) |

| Accessible parking aisles (≥5 ft) | 27 (54.0) | 13 (46.4) | 6 (60.0) | 8 (66.7) |

| Designated van-accessible spaces | 16 (32.0) | 9 (32.1) | 3 (30.0) | 4 (33.3) |

| Accessibility Feature | Delaware (n = 50) | NCC (n = 28) | KC (n = 10) | SC (n = 12) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Many | Some | Any Presence * | |||

| Clean/well-maintained sidewalks, trails, or paths | 14 (28.0) | 23 (46.0) | 8 (16.0) | 25 (89.3) | 10 (100) | 10 (83.3) |

| Buffer between sidewalk and street | 15 (30.0) | 11 (22.0) | 11 (22.0) | 22 (78.6) | 9 (90.0) | 6 (50.0) |

| Benches or seating along streets near the entrance | 0 (0.0) | 8 (16.0) | 17 (34.0) | 16 (57.1) | 7 (70.0) | 2 (16.7) |

| Trees/shade along streets near the entrance | 7 (14.0) | 17 (34.0) | 21 (42.0) | 26 (92.9) | 10 (100) | 9 (75.0) |

| Green space along streets near the entrance | 12 (24.0) | 25 (50.0) | 10 (20.0) | 26 (92.9) | 10 (100) | 11 (91.7) |

| Free of noise pollution | 8 (16.0) | 18 (36.0) | 14 (28.0) | 21 (75.0) | 10 (100) | 9 (75.0) |

| People loitering around the site present | 0 (0) | 1 (2.0) | 20 (40.0) | 14 (50.0) | 4 (40.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| Graffiti around the site present | 0 (0) | 2 (4.0) | 8 (16.0) | 9 (32.1) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Littering around the site present | 1 (2.0) | 7 (14.0) | 27 (54.0) | 25 (89.3) | 6 (60.0) | 4 (33.3) |

| Vacant buildings around the site present | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (8.0) | 3 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) |

| Street harassment around the site present | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (6.0) | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) |

| Pathways ≥ 5 feet wide | 24 (48.0) | 12 (24.0) | 8 (16.0) | 24 (85.7) | 10 (100) | 10 (83.3) |

| Path free of obstacles or hazards | 12 (24.0) | 18 (36.0) | 14 (28.0) | 24 (85.7) | 9 (90.0) | 11 (91.7) |

| Path cross slope ≤ 2% (1.1°) | 33 (66.0) | 5 (10.0) | 4 (8.0) | 25 (89.3) | 6 (60.0) | 11 (91.7) |

| Path surface smooth/firm (no gravel/dirt) | 29 (58.0) | 10 (20.0) | 4 (8.0) | 24 (85.7) | 9 (90.0) | 10 (83.3) |

| Accessibility Feature | Delaware (n = 50) | NCC (n = 28) | KC (n = 10) | SC (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restrooms | ||||

| Restroom present | 38 (76.0) | 21 (75.0) | 7 (70.0) | 10 (83.3) |

| Automatic door or open corridor entrance | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Minimal force (<5 lb) to open the restroom door | 31 (62.0) | 17 (60.7) | 4 (40.0) | 10 (83.3) |

| Door handles operable with a closed fist | 16 (32.0) | 8 (28.6) | 3 (30.0) | 5 (41.7) |

| Door opening ≥32″ wide | 28 (56.0) | 17 (60.7) | 4 (40.0) | 7 (58.3) |

| Stall handles/latches operable with a closed fist | 18 (36) | 11 (39.3) | 2 (20.0) | 5 (41.7) |

| Grab bars in the stall | 29 (58) | 17 (60.7) | 5 (50.0) | 7 (58.3) |

| Stall space for mobility device (60″ × 56–59″) | 27 (54.0) | 16 (57.1) | 4 (40.0) | 7 (58.3) |

| Physical Activity Areas | ||||

| Spaces within physical activity areas accessible for mobility devices | 44 (88.0) | 23 (82.1) | 10 (100) | 11 (91.7) |

| All | 13 (26.0) | 7 (25.0) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (33.3) |

| Many | 12 (24) | 5 (17.9) | 4 (40.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| Some | 19 (38.0) | 11 (39.3) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (33.3) |

| Playgrounds | ||||

| Ground material traversable by a mobility device | 32 (64.0) | 20 (71.4) | 4 (40.0) | 8 (66.7) |

| Elevated equipment with ramps or transfer platforms | 30 (60.0) | 14 (50.0) | 6 (60.0) | 10 (83.3) |

| Ground-level play components usable by a person using a mobility device | 31 (62.0) | 16 (57.1) | 5 (50.0) | 10 (83.3) |

| Multi-Use Trails | ||||

| Benches or rest areas along the trail | 34 (68.0) | 20 (71.4) | 7 (70.0) | 7 (58.3) |

| Firm, smooth surface on the trail | 32 (64.0) | 17 (60.7) | 8 (80.0) | 7 (58.3) |

| Trail width ≥5 ft for mobility devices | 38 (76.0) | 21 (75.0) | 9 (90.0) | 8 (66.7) |

| Trail free of obstacles or hazards | 24 (48.0) | 12 (42.9) | 7 (70.0) | 5 (41.7) |

| Trail has navigational aids | 6 (12.0) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (16.7) |

| Promotional Materials | ||||

| Electronic plain text (ASCII) | 4 (8.0) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Large print | 6 (12.0) | 4 (14.3) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (8.3) |

| Pictograms | 7 (14.0) | 5 (17.9) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (8.3) |

| Inclusion of persons with disabilities | 3 (6.0) | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) |

| Safety Feature | Delaware (n = 50) | NCC (n = 28) | KC (n = 10) | SC (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervision | ||||

| Adults are present when children use the equipment | 47 (94.0) | 26 (92.9) | 9 (90.0) | 12 (100) |

| Children are easily viewed on the equipment | 47 (94.0) | 27 (96.4) | 9 (90.0) | 11 (91.7) |

| Children are easily viewed in crawl spaces | 46 (92.0) | 26 (92.9) | 10 (100) | 10 (83.3) |

| Rules posted regarding expected behavior | 29 (58.0) | 15 (53.6) | 6 (60.0) | 8 (66.7) |

| Age-Appropriate Design | ||||

| Separate areas for ages 2–5 years and 5–12 years | 19 (38.0) | 10 (35.7) | 6 (60.0) | 3 (25.0) |

| Platforms have appropriate guardrails | 46 (92.0) | 25 (89.3) | 10 (100) | 11 (91.7) |

| Platforms allow a change in direction to get on/off the structure | 50 (100) | 28 (100) | 10 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Signage indicating the age group for the equipment provided | 32 (64.0) | 18 (64.3) | 8 (80.0) | 6 (50.0) |

| Equipment design prevents climbing outside the structure | 38 (76.0) | 22 (78.6) | 8 (80.0) | 8 (66.7) |

| Supporting structures prevent climbing on them | 42 (84.0) | 22 (78.6) | 9 (90.0) | 11 (91.7) |

| Fall Surfacing | ||||

| Suitable surfacing materials provided | 49 (98.0) | 28 (100) | 10 (100) | 11 (91.7) |

| Height of equipment is ≤8 ft | 35 (70.0) | 16 (57.1) | 8 (80.0) | 11 (91.7) |

| Appropriate depth of loose fill provided | 29 (58.0) | 15 (53.6) | 9 (90.0) | 5 (41.7) |

| The 6-foot use zone has appropriate surfacing | 45 (90.0) | 23 (82.1) | 10 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Concrete footings are covered | 49 (98.0) | 27 (96.4) | 10 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Surface free of foreign objects | 27 (54.0) | 14 (50.0) | 6 (60.0) | 7 (58.3) |

| Equipment Maintenance | ||||

| Equipment free of noticeable gaps | 48 (96.0) | 26 (92.9) | 10 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Equipment free of head entrapments | 45 (90.0) | 23 (82.1) | 10 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Equipment free of broken parts | 42 (84.0) | 23 (82.1) | 9 (90.0) | 10 (83.3) |

| Equipment free of missing parts | 47 (94.0) | 26 (92.9) | 10 (100) | 11 (91.7) |

| Equipment free of protruding bolts | 48 (96.0) | 26 (92.9) | 10 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Equipment is free of rust | 37 (74.0) | 19 (67.9) | 8 (80.0) | 10 (83.3) |

| Equipment is free of splinters | 47 (94.0) | 27 (96.4) | 9 (90.0) | 11 (91.7) |

| Equipment is free of cracks/holes | 43 (86.0) | 23 (82.1) | 10 (100) | 10 (83.3) |

| Mean Playground Accessibility a | 19.74 ± 2.92 | 19.11 ± 3.19 | 21.40 ± 1.51 | 19.83 ± 2.76 |

| Mean Life-Threatening Injury Risk b | 1.98 ± 1.53 | 2.43 ± 1.64 | 0.90 ± 0.88 | 1.83 ± 1.27 |

| Risk Classification: Safe | 31 (62) | 16 (57.1) | 9 (90.0) | 6 (50.0) |

| Risk Classification: On Way | 14 (28) | 8 (28.6) | 1 (10.0) | 5 (41.7) |

| Risk Classification: Potentially Hazardous | 4 (8) | 3 (10.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (8.3) |

| Risk Classification: At Risk | 1 (2) | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Obrusnikova, I.; Firkin, C.J.; Pennington, R.; Dixon, I.; Bilbrough, C. Statewide Assessment of Public Park Accessibility and Usability and Playground Safety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010139

Obrusnikova I, Firkin CJ, Pennington R, Dixon I, Bilbrough C. Statewide Assessment of Public Park Accessibility and Usability and Playground Safety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010139

Chicago/Turabian StyleObrusnikova, Iva, Cora J. Firkin, Riley Pennington, India Dixon, and Colin Bilbrough. 2026. "Statewide Assessment of Public Park Accessibility and Usability and Playground Safety" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010139

APA StyleObrusnikova, I., Firkin, C. J., Pennington, R., Dixon, I., & Bilbrough, C. (2026). Statewide Assessment of Public Park Accessibility and Usability and Playground Safety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010139