Co-Designing an Inclusive Stakeholder Engagement Strategy for Rehabilitation Technology Training Using the I-STEM Model

Highlights

- Equitable access to rehabilitation technologies is essential for reducing health inequalities, particularly for people with sensory, cognitive, or physical impairments.

- Training that is inaccessible or poorly designed can limit the effectiveness of rehabilitation technologies, undermining recovery outcomes and long-term independence.

- This study identifies systemic barriers that prevent diverse populations from benefiting fully from rehabilitation technologies.

- It provides evidence-based priorities for designing inclusive training approaches that support equitable participation in rehabilitation.

- Practitioners should adopt training models that address physical, sensory, and cognitive accessibility to ensure all users can engage effectively with rehabilitation technologies.

- Policymakers and researchers can use the co-created stakeholder engagement strategy to guide future intervention development and strengthen inclusive rehabilitation practices.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definitions

2.2. PPI and Co-Production Process

3. Results

3.1. PPI Contributor Characteristics

3.2. Evaluation of the PPI and Co-Design Process

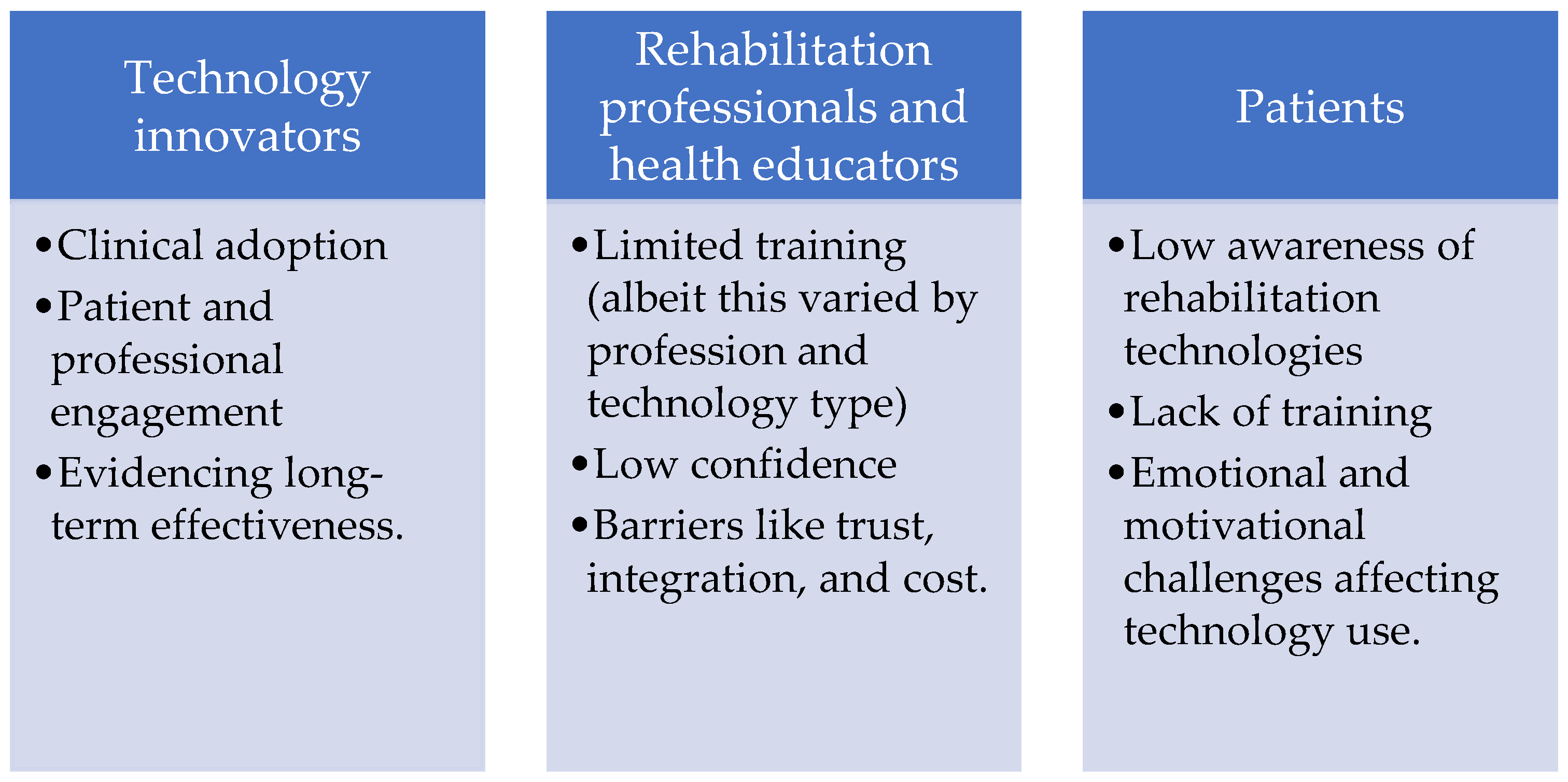

3.3. Identifying Overarching Challenges for Stakeholder Groups

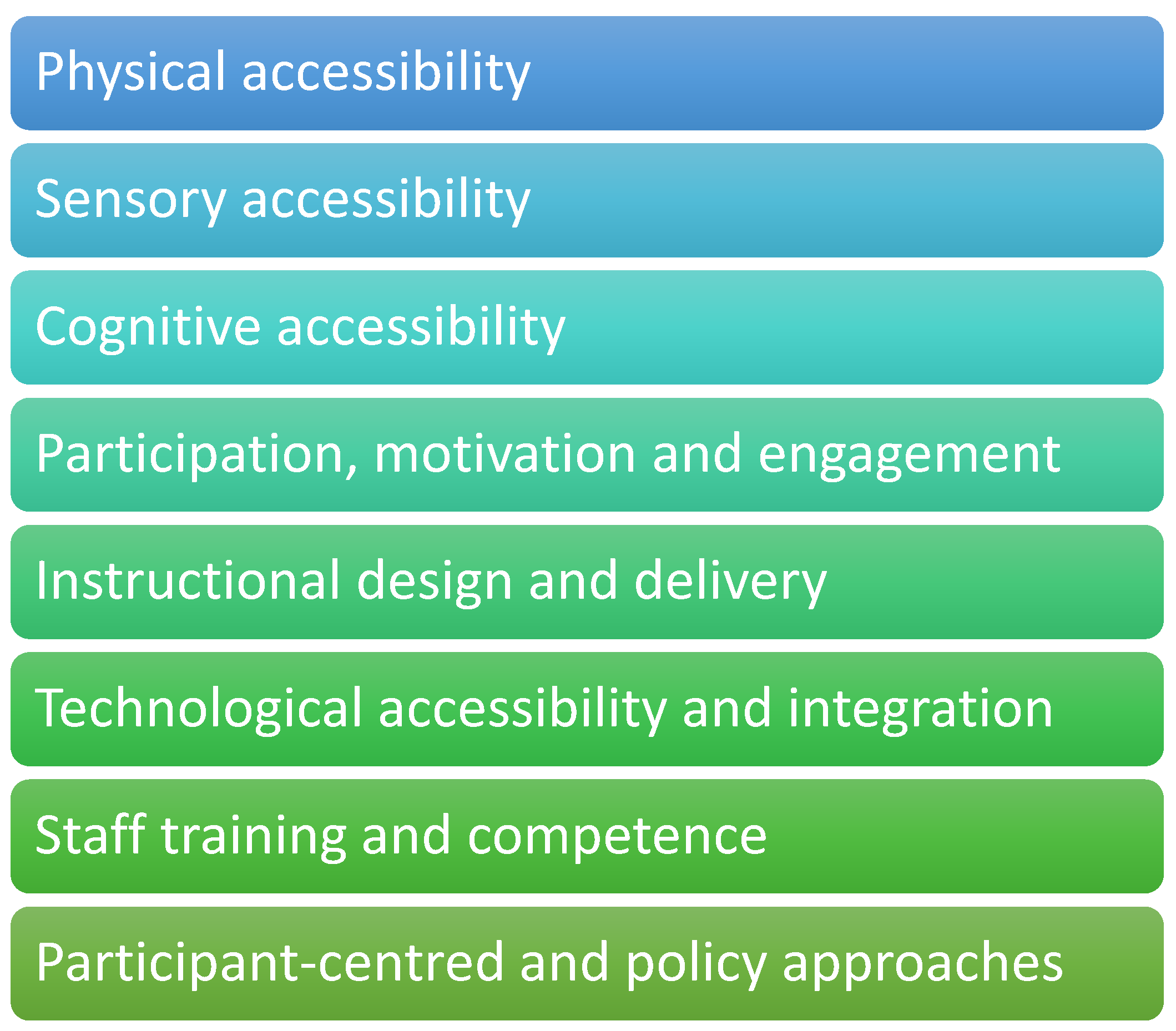

3.4. Detailing Considerations for Inclusivity and Accessibility

3.5. Specific Challenges for Rehabilitation Patients

- (i)

- Awareness and Access

- (ii)

- Overwhelm and Timing Considerations

- (iii)

- Complexity and Usability

- (iv) Cost and Affordability

- (v) Widening Inequity

- (vi)

- Practicality and Integration into Daily Life

- (vii)

- Confidence and Self-Efficacy

3.6. Specific Needs of Rehabilitation Patients

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPI | Patient and public involvement in research |

| NIHR | National Institute for Health and Care Research |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| GRIPP2 | Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public |

References

- Department of Health and Social Care. Research and Development Work Relating to Assistive Technology: 2023 to 2024. Corporate Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/assistive-technology-research-and-development-work-2023-to-2024/research-and-development-work-relating-to-assistive-technology-2023-to-2024 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Mitchell, J.; Shirota, C.; Clanchy, K. Factors that influence the adoption of rehabilitation technologies: A multi-disciplinary qualitative exploration. J. NeuroEngineering Rehabil. 2023, 20, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parnell, T.; Fiske, K.; Stastny, K.; Sewell, S.; Nott, M. Lived experience narratives in health professional education: Educators’ perspectives of a co-designed, online mental health education resource. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroll, T.; Escorpizo, R. Editorial: Patient and public involvement in disability and rehabilitation research. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2023, 4, 1307386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boltaboyeva, A.; Baigarayeva, Z.; Imanbek, B.; Ozhikenov, K.; Getahun, A.J.; Aidarova, T.; Karymsakova, N. A Review of Innovative Medical Rehabilitation Systems with Scalable AI-Assisted Platforms for Sensor-Based Recovery Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladugu, P.; Kumar, R.; Ong, J.; Waisberg, E.; Sporn, K. Virtual reality-enhanced rehabilitation for improving musculoskeletal function and recovery after trauma. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Ai, Y.; Wang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, A.; Hu, H.; Wang, Y. Barriers and facilitators to participation in electronic health interventions in older adults with cognitive impairment: An umbrella review. BMC Geriat. 2024, 24, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIHR. Guidance on Co-Producing a Research Project, April 2024. Available online: https://www.learningforinvolvement.org.uk/content/resource/nihr-guidance-on-co-producing-a-research-project/#:~:text=So%20what%20is%20co%2Dproduction,made%20to%20redress%20power%20differentials (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- UK Standards for Public Involvement. November 2023. Available online: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/news/nihr-announces-new-standards-public-involvement-research (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- UK Government Disability Unit and Cabinet Office. Guidance on Inclusive Communication. Last Updated 15 March 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/inclusive-communication (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Staniszewska, S.; Brett, J.; Simera, I.; Seers, K.; Mockford, C.; Goodlad, S.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; Barber, R.; Denegri, S.; et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: Tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ 2017, 358, j3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.; Rose, D.H.; Gordon, D.T. Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice; CAST Professional Publishing: Lynnfield, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, A.; OConnor, J.; Campbell, A.; Cooper, M. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1. W3C. 2018. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol. Available online: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Ocloo, J.; Garfield, S.; Franklin, B.D.; Dawson, S. Exploring the theory, barriers and enablers for patient and public involvement across health, social care and patient safety: A systematic review of reviews. Health Res. Policy Sys. 2021, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, H.; Abbott-Fleming, V.; Greaves, S.; Somerset, S.; Chaplin, W.J.; Wainwright, E.; Walker-Bone, K. Five years of patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) in the development and evaluation of the Pain-at-Work toolkit to support employees’ self-management of chronic pain at work. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2025, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.A.; Pradhan, S.; Levin, M.F.; Hancock, N.J. Uptake of Technology for Neurorehabilitation in Clinical Practice: A Scoping Review. Phys. Ther. 2024, 104, pzad140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potthoff, S.; Rapley, T.; Finch, T.; Gibson, B.; Clegg, H.; Charlton, C. The Implementation STakeholder Engagement Model (I-STEM) Toolkit. 2023. Available online: https://arc-nenc.nihr.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/I-STEM-Toolkit-Oct-2024-v1.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Browne, J.; Dorris, E.R. What Can We Learn From a Human-Rights Based Approach to Disability for Public and Patient Involvement in Research? Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2022, 3, 878231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, K.R.; Ellis, T.D. Advances in Rehabilitation Technology to Transform Health. Phys. Ther. 2024, 104, pzae008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veras, M.; Auger, L.P.; Sigouin, J.; Gheidari, N.; Nelson, M.L.; Miller, W.C.; Hudon, A.; Kairy, D. Ethics and Equity Challenges in Telerehabilitation for Older Adults: Rapid Review. JMIR Aging 2025, 8, e69660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, D.; Ní Shé, É.; McCarthy, M.; Thornton, S.; Doran, T.; Smith, F.; O’Brien, B.; Milton, J.; Savin, B.; Donnellan, A.; et al. Enabling public, patient and practitioner involvement in co-designing frailty pathways in the acute care setting. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, J.; Gillani, N.; Saied, I.; Alzaabi, A.; Arslan, T. Patient and public involvement in the co-design and assessment of unobtrusive sensing technologies for care at home: A user-centric design approach. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attal, B.; Leeding, J.; van der Scheer, J.W.; Barry, Z.; Crookes, E.; Igwe, S.; Lyons, N.; Stanford, S.; Dixon-Woods, M.; Hinton, L. Integrating patient and public involvement into co-design of healthcare improvement: A case study in maternity care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tscherning, S.C.; Jensen, A.L.; Bekker, H.L.; Vedelø, T.W.; Finderup, J.; Rasmussen, G.S.; Østergaard, J.A.; Jensen, F.O.; Rodkjaer, L.Ø. How are patient partners involved in health service research? A scoping review of reviews. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2025, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Consideration | Description |

|---|---|

| Physical Accessibility | Inclusive training environments must be physically barrier-free, with ramps, wide doorways, accessible restrooms, and adjustable workstations. Rehabilitation technologies should be positioned for safe, independent use by wheelchair users or those with prosthetics, with equipment adaptable to varied body sizes and functional levels. Emergency procedures must also account for mobility limitations. “When I arrived, the doorways were too narrow for my prosthetic crutches.” (amputation) |

| Sensory Accessibility | Training must accommodate visual and hearing impairments. Materials should be available in Braille, large print, audio, and screen-reader-compatible formats, supported by high-contrast displays, tactile markers, and verbal descriptions. For hearing impairments, captioning, sign language interpretation, written instructions, and subtitled tutorials are essential, alongside visual alerts and diagrams. “The trainer kept explaining things verbally, but without captions or an interpreter I missed half of it. I needed visual instructions to feel included.” (hearing loss) |

| Cognitive Accessibility | Clear communication and structured learning are vital for those with cognitive impairments. Instructors should use plain language, multimodal delivery (verbal, visual, and hands-on), and break complex procedures into sequential steps with pictorial guides. Extra time for repetition and distraction-free environments further support comprehension and focus. “After my injury, I struggle to follow long explanations. Breaking the steps into simple pictures and repeating them slowly made all the difference.” (brain injury) |

| Participation, Motivation, and Engagement | Motivation is strengthened when training is meaningful, empowering, and aligned with personal rehabilitation goals. Interactive approaches—such as gamification, simulations, and real-world tasks-enhance engagement, while peer support fosters belonging. For those with cognitive or sensory impairments, clarity, positive feedback, and emotional support are critical. Staff empathy and adaptability build trust, while sensitivity to timing and mood prevents disengagement. Co-designing training with participants ensures relevance and ownership. “I stayed motivated when the exercises connected to real tasks, like making a cup of tea. It reminded me why I was doing this in the first place.” (stroke) |

| Instructional Design and Delivery | Grounded in the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework [12], inclusive training should provide multiple means of engagement, representation, and expression. Learners benefit from individual pacing, continuous accessible feedback, and opportunities for peer collaboration, which reinforce confidence and inclusion. “Because my fatigue varies day to day, having the option to go at my own pace meant I could keep learning without feeling defeated.” (multiple sclerosis) |

| Technological Accessibility and Integration | Rehabilitation technologies must themselves be accessible, complying with WCAG 2.1 [13] and supporting assistive tools such as screen readers, voice control, and adaptive switches. Customisable outputs and integration of devices like speech-to-text systems ensure full participation, positioning technology as an enabler rather than a barrier. “The software had no subtitles, so I couldn’t follow the video prompts. Technology should help me, not shut me out.” (hearing loss) |

| Staff Training and Competence | Instructor competence is central to inclusion. Professionals should be trained in disability awareness, adaptive teaching, and assistive technology use. Empathy, flexibility, and collaboration foster supportive environments, while ongoing professional development ensures responsiveness to emerging inclusive practices. “She [therapist] took time to listen and adapt the instructions, that gave me confidence. Without that I would have given up.” (stroke) |

| Participant-Centred and Policy Approaches | Training should be guided by participant-centred principles, tailoring goals and methods to individual needs. Institutional and policy frameworks must align with disability legislation, such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD, [14]), embedding inclusion as both compliance and culture, thereby promoting empowerment and equal participation. “When I was asked about my personal goals, I felt respected. It wasn’t just about ticking boxes then getting me out of there, it was about my life.” |

| Key Challenges | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Awareness and access | “As a patient, one of the biggest challenges is even knowing what’s available, where it’s available from, what use is it to me and the cost. Most of us are never told about rehabilitation technologies. A lot of the time we generally only find out by chance, or we research ourselves, or through other people. This creates a real inequality, because the people who would benefit most may never get the chance, or may never know what’s out there for them.” (amputation) “They’re too busy doing this and that, nothing said and then you hear about something but where would I find it?” (multiple sclerosis) |

| Overwhelm and timing issues | “When you’re first adjusting to life-changing disability or injury, you’re often overwhelmed—physically, emotionally and mentally. You generally deal with what’s happened that day, what’s the most important and what capacity you have as well. That’s not the time to be handed complex technologies without support which can and does happen. If people are struggling with low mood or pain or even just after a life changing injury or complex medical procedures, the technology can feel like another burden rather than something empowering. Being simply to press that button and it does this and that does something else when you’ve just had surgery a couple of days ago, you’re not going to be able to take it all in and understand how it can help or what good it’s going to do.” (amputation) “It’s changed your life, rushing around, seeing this person, that person, surgery, hospitals. All I want to do is sit and cry about what I have lost. Not the time to start saying ‘want to try this new thing?” (stroke) |

| Complexity and usability | “A lot of the technology looks amazing, but it often feels designed for clinicians or engineers, not patients. If something is too complicated, has too many steps, or isn’t intuitive, it becomes frustrating very quickly. Many people now have ‘smart watches’ that can do great things but for many they’re just too complicated to use on a daily basis or to simply just to use them or don’t understand how to interpret the results from the tech to send on to the healthcare professional. People will just give up, which wastes the potential of the technology. It is also a waste of money if you don’t get good use out of it or if you’re not using it to its full potential. Not everyone is good at using tech whatever age you’re at which can be a big barrier to many.” (amputation) “Do they make what people want? Have they asked what we need? It’s so complicated, even those apps with all the different functions and you don’t use it, but if they asked us, we’d have said get rid of this and that. I don’t want it. Just give me the basics.” (brain injury) |

| Cost and affordability | “Many pieces of technology are expensive and not funded, which means only some people can access them. That leaves a lot of people feeling left behind or without a tool that could be extremely valuable which could improve someone’s quality of life, which doesn’t seem fair.” (amputation) “If you don’t have the money, are they going to give it to you? Or no, more likely you’ll be left on the side?” (hearing loss) |

| Widening inequity | “A lot of tech can and does rely on the internet, WiFi or integration with smart phones or tablets. Not everyone has access to things like smart phones or even the internet … which makes it unfair and unjust for those who don’t have access to the internet or IT.” (amputation) “The ones that make it, they’ve got all that fancy stuff, but I like it simple. I don’t know what connects to what, and they use words I don’t know about. Is someone going to set it up, fix it when it goes wrong?” (hearing loss) |

| Practicality | “Some of the tech doesn’t fit well into real life. They might work brilliantly in a lab, but in a patient’s home or community setting, they can be too bulky, need too much space, or don’t integrate easily with daily routines.” (amputation) “I work from home and need to be able to use it without it becoming a problem due to lack of space.” (multiple sclerosis) |

| Confidence | “For some people, especially if they’ve had bad experiences before, there can be a lack of confidence. You worry—will it work for me, or will I fail at it? That sense of not wanting to ‘get it wrong’ can be a barrier for many people. Also, confidence in using the tech itself. If you’re not a confident tech person then adding in a wearable or another piece of tech that you just don’t get is a waste of time, money and effort, especially if you’re shown how to use it once and then you’re left to use it yourself.” (amputation) “I don’t know if I could. You know it’s so much, so much going on and if I won’t get it straight away then are they gonna sit down and go over and over? You already think you can’t do anything, and they probably think you can’t do anything.” (stroke) |

| Item | Detail and Requirements |

|---|---|

| Plain language & step-by-step learning | People need explanations in clear, non-technical, easy-to-understand language-without the use of any form of jargon or medical/technology specific wording. Training should be broken down into simple, manageable steps rather than a huge instruction manual that overwhelms you from the start or steps that miss important points. |

| Repetition and reinforcement | When you’re adjusting to disability, fatigue and brain fog can make it hard to retain new information. So having either regular refreshers or repetition of the training are essential, not a one-time explanation. |

| Hands-on practice | Seeing and trying the technology with guided support is key. People learn best when they can practice at their own pace, with someone patient enough to repeat things as many times as needed. |

| Tailored to individual needs and using different forms of learning | Training and education should recognise that everyone’s starting point is different in terms of ability, confidence, mood and energy. Some may need very short sessions, while others may want more in-depth training. Using different forms of training is important; some people learn by watching a video and following along, others prefer watching someone physically use something, and others prefer step by step written guides or pictorial step guides. |

| Individualised pace | Training needs to be adapted to each person’s abilities, confidence level, and learning style. For example, someone with limited hand movement will need training adapted for that. Or if you learn slower and need more repetition, you don’t want to be in a group that speeds through everything, and you’re left behind. |

| Psychological readiness | Training needs to consider mental health. If a person is anxious, depressed, or still adjusting to their condition, that will affect how much they can take on. Offering emotional support alongside technology training can often make a big difference. |

| Ongoing support, not one-off | It’s not enough to show someone once and leave them to it. People need follow-up, ongoing support and a way to ask questions when problems come up at home. You can’t expect someone to hear a trainer say what you need to do on one occasion and then use the tech yourself. That’s when people give up and stop using things. |

| Peer learning | Sometimes the best training comes from other people who’ve already used the tech. Seeing someone like you use the tech successfully can very often build confidence and make it feel more achievable for you to use it. |

| Family and carer involvement | Often carers or family members are the ones helping patients use technology at home. Training should include them too, so everyone feels confident and supported. It can also help if someone is with you when you’re learning a new piece of tech because they will most likely remember instructions as they’re generally not in any pain or fatigue. |

| Accessibility of information | Training resources should be available in different formats—written guides, videos, easy-read, and online resources—so people can choose what works best for them. “We’re not all clones, we don’t all learn the same way!”. |

| Cultural & social awareness | Training should also consider cultural factors and health literacy. Some people may feel less confident speaking up if they don’t understand or come from a culture where it’s impolite to ask or disturb a class or if they are used to their husband/partner speaking up for them. Training should always be inclusive and sensitive. |

| Visual and practical learning | Not everyone learns well from a written manual. Training should include demonstrations, short videos, diagrams, podcasts and hands-on practice. Real-life examples of how someone might use the technology at home or at work make it easier to understand. |

| Supportive environment | The way training is delivered matters as much as the content to people. We just need an encouraging, non-judgmental environment where we don’t feel embarrassed if we ‘get it wrong’ or we need something explained again. |

| Clear information on benefits and limits | We need realistic expectations! Training should explain what the technology can do, but also what it can’t. That way, people aren’t left disappointed or feeling like they’ve failed if it doesn’t ‘fix’ everything. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Blake, H.; Abbott-Fleming, V.; Abdalrahim, A.; Horrocks, M. Co-Designing an Inclusive Stakeholder Engagement Strategy for Rehabilitation Technology Training Using the I-STEM Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2026, 23, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010013

Blake H, Abbott-Fleming V, Abdalrahim A, Horrocks M. Co-Designing an Inclusive Stakeholder Engagement Strategy for Rehabilitation Technology Training Using the I-STEM Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2026; 23(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlake, Holly, Victoria Abbott-Fleming, Asem Abdalrahim, and Matthew Horrocks. 2026. "Co-Designing an Inclusive Stakeholder Engagement Strategy for Rehabilitation Technology Training Using the I-STEM Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 23, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010013

APA StyleBlake, H., Abbott-Fleming, V., Abdalrahim, A., & Horrocks, M. (2026). Co-Designing an Inclusive Stakeholder Engagement Strategy for Rehabilitation Technology Training Using the I-STEM Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 23(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph23010013