Postpartum Women’s Body Dissatisfaction: A Systematic Review of Theoretical Models and Regression Analyses

Abstract

1. Introduction

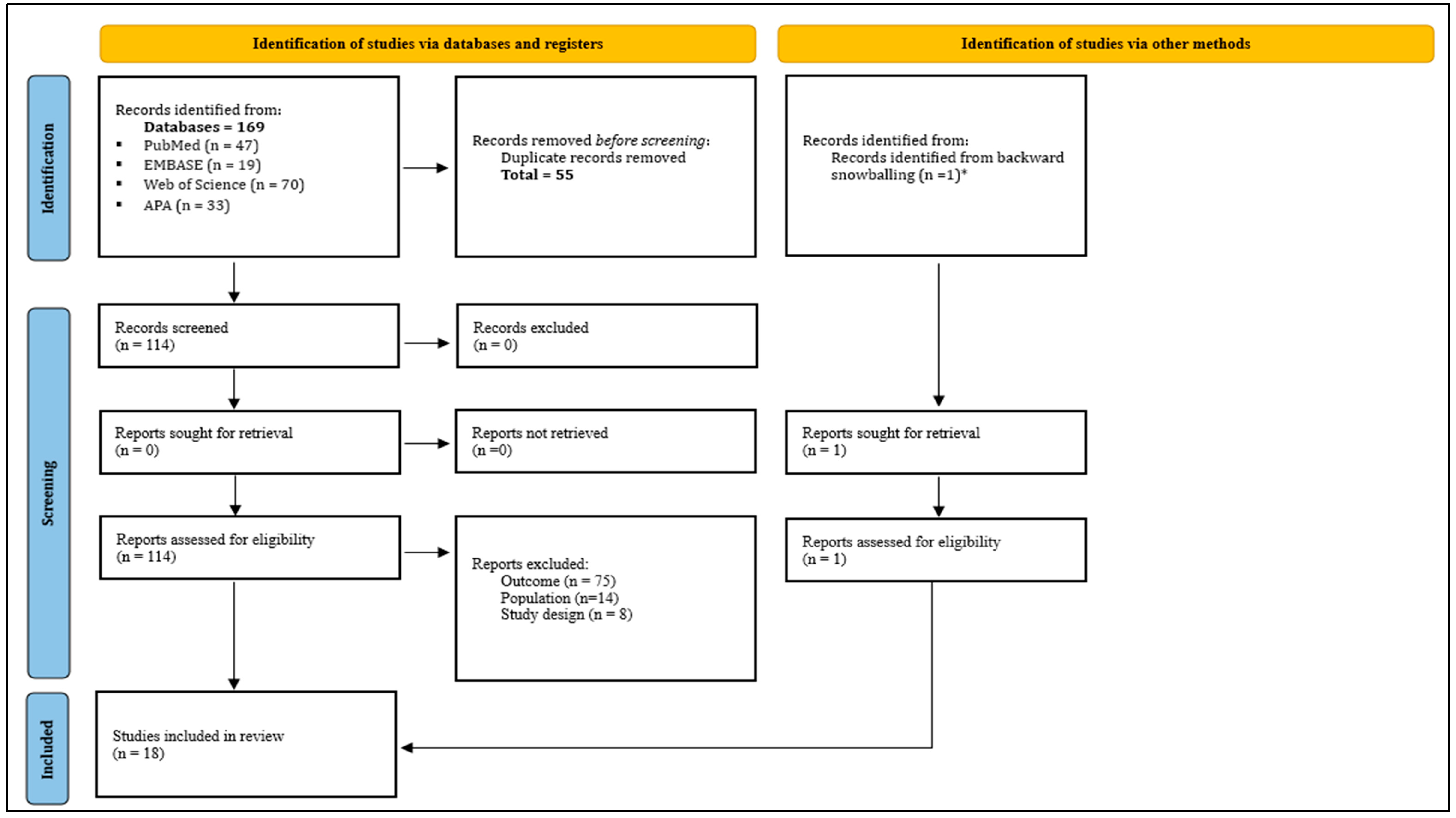

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Collection and Analyses

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

| Author/Year Country | N Postpartum Period Age (Years) | Outcomes and Instruments Measured * | Type of Design Data Analysis | Outcomes Related to Body Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walker et al. (2002) [39] USA | N = 283 Postpartum period: immediately or less than 6 weeks Age: Anglo-American 22.8 (± 4.4), African American 22 (2 ± 3.8), Anglo-Hispanic 21.9 (± 3.4) |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Hierarchical regression | Body image was correlated with depressive symptoms across all ethnicities. Weight was the main component related to body dissatisfaction. |

| Huang and Dai (2007) [49] China | N = 602 Postpartum period: less than 6 months Age: 30.22 (±4.35) |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Multiple linear regression | The greater the weight retention during the postpartum, the lower the perceived satisfaction with body image. |

| Downs et al. (2008) [40] USA | N = 230 Postpartum period: less than 6 weeks Age: 30.05 (±4.13) |

| Prospective longitudinal cohort study Hierarchical regression | Body image satisfaction was negatively correlated with depressive symptoms. |

| Sweeney and Fingerhut (2013) [41] USA | N = 46 Postpartum period: less than 2 months Age: 27.17 (±6.59) |

Concern Over Mistakes subscale Doubts About Actions subscale of Frost’s Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale

| Prospective longitudinal cohort study Hierarchical multiple regression | Third-trimester of pregnancy body dissatisfaction was identified as a risk factor for postpartum depression. |

| Walker et al. (2013) [42] USA | N = 419 Postpartum period: less than 6 weeks Age: 22.3 (±3.9) |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Poisson and multiple linear regression | Higher BMI was associated with increased body dissatisfaction. |

| Han et al. (2016) [34] Norway | N = 39.915 Postpartum period: less than 18 months Age: NR |

| Prospective longitudinal cohort study Binary logistic regression | Concerns about body image mediated the association between increasing weight and the depressive symptoms, regardless of weight. |

| Walker et al. (2016) [43] USA | N = 168 Postpartum period: less than 6 months Age: Lower income group: 28.9 (±5.6) Higher income group: 32.8 (±4.8) |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Linear and logistic regression | Greater social support was correlated with lower body dissatisfaction. |

| Jawed-Wessel et al. (2017) [44] USA | N = 168 Postpartum period: less than 12 months Age: 29.72 (±4.03) |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Hierarchical multiple regression | Body satisfaction/dissatisfaction varied according to the type of delivery. Negative correlation: body dissatisfaction with body awareness during intimacy increased. Body dissatisfaction with genital self-image and age. Sociocultural pressure from media, partners, and friends significantly predicted body dissatisfaction mediated by the thin ideal. |

| Lovering et al. (2018) [16] USA | N = 474 Postpartum period: less than 6 months Age: 30.9 (±4.5) |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Structural equation modeling | Sociocultural pressure from media, partners, and friends significantly predicted body dissatisfaction mediated by the thin ideal. |

| Rodgers et al. (2018) [45] USA | N = 151 Postpartum period: less than 6 months Age: 32.77 (±4.47) |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Path analysis | Positive correlation: Body dissatisfaction with desired weight loss, body surveillance, breastfeeding barriers, depressive symptoms, and eating disorders. Negative correlation: Body dissatisfaction with breastfeeding self-efficacy. |

| Shloim et al. (2019) [50] Israel and United Kingdom | N = 61 Postpartum period: less than 24 months Age: Israel: 30.4 (±3.8) United Kingdom: 34.4 (±3.2) |

| Prospective longitudinal cohort study Hierarchical linear modeling | Body image dissatisfaction had a positive correlation with BMI. |

| Schlaff et al. (2020) [46] USA | N = 269 Postpartum period: less than 12 months Age: 30.4 (±3.9) |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Multiple linear regression | Postpartum body satisfaction was negatively correlated with postpartum depressive symptoms. |

| Tavakoli et al. (2021) [18] Iran | N = 300 Postpartum period: less than 6 months Age: 29.77 (±5.9) |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Multiple linear regression | BMI was the main predictor to body dissatisfaction. |

| Kapa et al. (2022) [31] USA | N = 204 Postpartum period: between 2 weeks and 6 months Age: Between 27 and 30 years old. |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Multiple linear regression | Body satisfaction was positively correlated with breastfeeding self-efficacy and experiences. |

| Kariuki et al. (2022) [32] Kenya | N = 567 Postpartum period: less than 10 weeks Age: 25.9 |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Multiple linear regression | Body dissatisfaction was positively correlated with depression |

| Rodgers et al. (2022) [47] USA | N = 156 Postpartum period: less than 6 weeks Age: 32.7 (±4.7) |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Path analysis | Body dissatisfaction was positively correlated with high levels of internalization of the thin ideals and partner appearance pressure. |

| Bakhteh et al. (2023) [48] Iran | N = 150 Postpartum period: less than 6 weeks Age: 28.60 (±4.5) |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Linear regression | Negative body image was a predictor of postpartum depression symptoms. |

| Acar Bektaş and Öcalan (2023) [29] Turkish | N = 197 Postpartum period: less than 1 week Age: 29.33 (±5.88) |

| Descriptive correlational (cross-sectional) Multiple linear regression | There was a significant and positive relationship between women’s body image and their genital self-image. |

| Author/Year | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walker et al. (2002) [39] | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Moderate |

| Huang and Dai (2007) [49] | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | U | Y | Y | High |

| Walker et al. (2013) [42] | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Moderate |

| Walker et al. (2016) [43] | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Moderate |

| Jawed-Wessel et al. (2017) [44] | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | U | Moderate |

| Lovering et al. (2018) [16] | U | N | N | Y | U | Y | U | Y | U | Low |

| Rodgers et al. (2018) [45] | U | N | N | Y | U | Y | U | Y | U | Low |

| Schlaff et al. (2020) [46] | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | U | Y | N | Moderate |

| Tavakoli et al. (2021) [18] | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Low |

| Kapa et al. (2022) [31] | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | U | Y | Y | Moderate |

| Kariuki et al. (2022) [32] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Low |

| Rodgers et al. (2022) [47] | Y | N | N | Y | U | Y | N | Y | N | Moderate |

| Bakhteh et al. (2023) [48] | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | U | Moderate |

| Acar Bektaş and Öcalan (2023) [29] | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Moderate |

| Author/Year | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Total Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downs et al. (2008) [40] | Y | Y | U | Y | U | U | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Moderate |

| Sweeney and Fingerhut (2013) [41] | Y | Y | U | Y | U | U | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Moderate |

| Han et al. (2016) [34] | Y | Y | U | Y | U | Y | U | Y | U | U | Y | Moderate |

| Shloim et al. (2019) [50] | Y | Y | U | U | U | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Moderate |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis |

| PICO | Patient, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome |

| APA | American Psychological Association |

| BCS | Body Cathexis Scale |

| CEDS | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale |

| BIS | Body Image Scale |

| BDI | Beck’s Depression Inventory |

| BSS | Body Satisfaction Scale |

| BAQ | Body Attitudes Questionnaire |

| EPDS | Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Inventory |

| MBSRQ | Multidimensional Self-Body Relationships |

| RSES | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale |

| FGSIS | Female Genital Self-Image Scale |

| BSES | Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale |

| EDI | Eating Disorder Inventory |

| BMI | body mass index |

| NR | Not reported |

| USA | United States of America |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

Appendix A

- ((Postpartum Period) OR (Period, Postpartum)) OR (Postpartum)) OR (Postpartum Women)) OR (Women, Postpartum)) OR (Puerperium)

- (((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((Latent Class Analysis) OR (Latent Class Analysis)) OR (LatentClass Analyses)) OR (Latent Variable Modeling)) OR (Latent Variable Modelings)) OR (Modeling, Latent Variable)) OR (Variable Modeling, Latent)) OR (Structural Equation Modeling)) OR (Modeling, Structural Equation)) OR (Structural Equation Modelings)) OR (Probabilistic Latent SemanticAnalysis)) OR (Latent Class Model)) OR (Latent Class Models)) OR (Model, Latent Class)) OR (Models, Theoretical)) OR (Models, Theoretical)) OR (Model, Theoretical)) OR (Theoretical Model)) OR (Theoretical Models)) OR (Models, Theoretic)) OR (Models (Theoretical))) OR (Experimental Model)) OR (Model, Experimental)) OR (Models, Experimental)) OR (Experimental Models)) OR (Mathematical Model)) OR (Mathematical Models)) OR (Model, Mathematical)) OR (Models, Mathematical)) OR (Theoretical Study)) OR (Studies, Theoretical)) OR (Study, Theoretical)) OR (Theoretical Studies)) OR (Regression Analysis)) OR (Regression Analysis)) OR (Analysis, Regression)) OR (Analyses, Regression)) OR (Regression Analyses)) OR (Regression Diagnostics)) OR (Diagnostics, Regression)) OR (Statistical Regression)) OR (Regression, Statistical)) OR (Regressions, Statistical)) OR (Statistical Regression)

- ((((((((((((((((((((((Body Images) OR (Image, Body)) OR (Body Identity)) OR (Identity, Body)) OR (Body Representation)) OR (Body Representations)) OR (Representation, Body)) OR (Body Schema)) OR (Body Schemas)) OR (Schema, Body)) OR (Dissatisfaction, Body)) OR (Body ImageDissatisfaction)) OR (Body Image Dissatisfactions)) OR (Dissatisfaction, Body Image)) OR (Dissatisfactions, Body Image)) OR (Image Dissatisfaction, Body)) OR (Image Dissatisfactions, Body)) OR (Negative Body Image)) OR (Body Image, Negative)) OR (Body Images, Negative)) OR (Image, Negative Body)) OR (Images, Negative Body)) OR (Negative Body Image)

- 1 AND 2 AND 3

- (((((((((((((((((((((((((ALL = (Latent Class Analysis)) OR ALL = (Latent Class Analysis)) OR ALL = (Latent Class Analyses)) OR ALL = (Latent Variable Modeling)) OR ALL = (Latent Variable modeling)) OR ALL = (Modeling, Latent Variable)) OR ALL = (Variable Modeling, Latent)) OR ALL = (Structural Equation Modeling)) OR ALL = (Modeling, Structural Equation)) OR ALL = (Structural Equation modeling)) OR ALL = (Probabilistic Latent Semantic Analysis)) OR ALL = (Latent Class Model)) OR ALL = (Latent Class Models)) OR ALL = (Model, Latent Class)) OR ALL = (Models, Theoretical)) OR ALL = (Models, Theoretical)) OR ALL = (Model, Theoretical)) OR ALL = (Theoretical Model)) OR ALL = (Theoretical Models)) OR ALL = (Models, Theoretic)) OR ALL = (Models (Theoretical))) OR ALL = (Experimental Model)) OR ALL = (Model, Experimental)) OR ALL = (Models, Experimental)) OR ALL = (Experimental Models))

- ((((((((((((((((((((((ALL = (Mathematical Model)) OR ALL = (Mathematical Models)) OR ALL = (Model, Mathematical)) OR ALL = (Models, Mathematical)) OR ALL = (Theoretical Study)) OR ALL = (Studies, Theoretical)) OR ALL = (Study, Theoretical)) OR ALL = (Theoretical Studies)) OR ALL = (Regression Analysis)) OR ALL = (Regression Analysis)) OR ALL = (Analysis, Regression)) OR ALL = (Analyses, Regression)) OR ALL = (Regression Analyses)) OR ALL = (Regression Diagnostics)) OR ALL = (Diagnostics, Regression)) OR ALL = (StatisticalRegression)) OR ALL = (Regression, Statistical)) OR ALL = (Regressions, Statistical)) OR ALL = (Statistical Regression)) OR ALL = (Biopsychosocial Models)) OR ALL = (Model, Biopsychosocial)) OR ALL = (Biopsychosocial Model)

- (((((((((((((((((((((((ALL = (Body Images)) OR ALL = (Image, Body)) OR ALL = (Body Identity)) OR ALL = (Identity, Body)) OR ALL = (Body Representation)) OR ALL = (Body Representations)) OR ALL = (Representation, Body)) OR ALL = (Body Schema)) OR ALL = (Body Schemas)) OR ALL = (Schema, Body)) OR ALL = (Dissatisfaction, Body)) OR ALL = (Body Image Dissatisfaction)) OR ALL = (Body Image dissatisfaction)) OR ALL = (Dissatisfaction, Body Image)) OR ALL = (dissatisfaction, Body Image)) OR ALL = (ImageDissatisfaction, Body)) OR ALL = (Image dissatisfaction, Body)) OR ALL = (Negative Body Image)) OR ALL = (Body Image, Negative)) OR ALL = (Body Images, Negative)) OR ALL = (Image, Negative Body)) OR ALL = (Images, Negative Body)) OR ALL = (Negative Body Image)) OR ALL = (body image)

References

- Chauhan, G.; Tadi, P. Physiology, postpartum changes. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rezende Filho, J. Obstetrícia fundamental. In Obstetrícia Fundamental; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2024; pp. 295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Brasil. Parto, Aborto e Puerpério: Assistência Humanizada à Mulher; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mckinney, J.; Keyser, L.; Clinton, S.P.; Pagliano, C. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: Optimizing postpartum care. Obstet. Gyneco 2018, 132, 784–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berens, P. Overview of the postpartum period: Normal physiology and routine maternal care. In UptoDate; UpToDate, Inc.: Waltham, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 15, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ricci, S.S. Enfermagem Materno-Neonatal e Saúde da Mulher; Grupo Gen-Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.F.; Target, C.; Liddelow, C.; Burke, K.J. Bouncing back with bliss: Nurturing body image and embracing intuitive eating in the postpartum: A cross-sectional replication study. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R.; Mottola, M.F.; Artal, R. Review of recent physical activity guidelines during pregnancy to facilitate advice by health care providers. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2019, 74, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadekar, A.; Karmarkar, A.; Chaudhury, S.; Saldanha, D.; Patil, J. Biopsychosocial correlates of emotional problems in women during pregnancy and postpartum period. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2023, 32 (Suppl. S1), S141–S146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinoni, M.; Solorzano, C.S.; Grano, C. A prospective study on body image disturbances during pregnancy and postpartum: The role of cognitive reappraisal. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1200819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrachan-Fletcher, E.; Veldhuis, C.; Lively, N.; Fowler, C.; Marcks, B. The reciprocal effects of eating disorders and the postpartum period: A review of the literature and recommendations for clinical care. J. Womens Health 2008, 17, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, E.L.; Smith, D.M.; Wittkowski, A. Women’s experiences of their pregnancy and postpartum body image: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’loghlen, E.; Galligan, R. Disordered eating in the postpartum period: Role of psychological distress, body dissatisfaction, dysfunctional maternal beliefs and self-compassion. J. Health Psychol. 2022, 27, 1084–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P.D. What is body image? Behav. Res. Ther. 1994, 32, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F.; Smolak, L. Body Image: A Handbook of Science, Practice, and Prevention, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lovering, M.E.; Rodgers, R.F.; George, J.E.; Franko, D.L. Exploring the tripartite influence model of body dissatisfaction in postpartum women. Body Image 2018, 24, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmeier, H.; Hill, B.; Haycraft, E.; Blewitt, C.; Lim, S.; Meyer, C.; Skouteris, H. Maternal body dissatisfaction in pregnancy, postpartum and early parenting: An overlooked factor implicated in maternal and childhood obesity risk. Appetite 2020, 147, 104525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, M.; Hasanpoor-Azghady, S.B.; Farahani, L.A. Predictors of mothers’ postpartum body dissatisfaction based on demographic and fertility factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.F.; Bolton, K.; Madsen, J.; Burke, K.J. A systematic review of influences and outcomes of body image in postpartum via a socioecological framework. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2023, 43, 789–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, M.L.; Ertel, K.A.; Dole, N.; Chasan-Taber, L. The role of body image in prenatal and postpartum depression: A critical review of the literature. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2015, 18, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, B.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Broadbent, J.; Skouteris, H. The meaning of body image experiences during the perinatal period: A systematic review of the qualitative literature. Body Image 2015, 14, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, E.; Hill, B.; McPhie, S.; Skouteris, H. The associations between depressive and anxiety symptoms, body image, and weight in the first year postpartum: A rapid systematic review. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2018, 36, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley-Hewitt, A.G.; Owen, A.L. A systematic review examining the association between female body image and lithe intention, initiation and duration of post-partum infant feeding methods (breastfeeding vs bottle-feeding). J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilder, P.; Wertman, R. Body Image: The Constructive Energies of the Psyche; Martins Fontes: São Paulo, Brazil, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim, L.D.A.F.; Fiaccone, R.; Santos, C.; Moraes, L.; Oliveira, N.; Oliveira, S.; dos Santos, T.N.L. Modelagem com Equações Estruturais: Princípios Básicos e Aplicações; Universidade Federal da Bahia: Salvador, Brazil, 2012; Available online: https://repositorio.ufba.br/handle/ri/17684 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Neves, J.A.B. Modelo de Equações Estruturais: Uma Introdução Aplicada; Escola Nacional de Administração Pública: Brasília, Brazil, 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.enap.gov.br/handle/1/3334 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Lewis, S. Regression analysis. Pract. Neurol. 2007, 7, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza Filho, B.A.B.D.; Struchiner, C.J. Uma proposta teórico-metodológica para elaboração de modelos teóricos. Cad. Saúde Coletiva 2021, 29, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar Bektaş, H.; Öcalan, D. The relationship between women’s mode of delivery, body image, self-respect, and genital self-image. Int. Urogynecology J. 2023, 34, 2885–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, P.R.B. Análise de Correlação e Medidas de Associação; Universidade Federal do Paraná: Curitiba, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kapa, H.M.; Litteral, J.L.; Keim, A.S.; Jackson, J.L.; Schofield, K.A.; Crerand, C.E. Body image dissatisfaction, breastfeeding experiences, and self-efficacy in postpartum women with and without eating disorder symptoms. J. Hum. Lact. 2022, 38, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariuki, E.W.; Kuria, M.W.; Were, F.N.; Ndetei, D.M. Predictors of postnatal depression in the slums Nairobi, Kenya: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.Y.; Brewis, A.A.; Wutich, A. Body image mediates the depressive effects of weight gain in new mothers, particularly for women already obese: Evidence from the Norwegian mother and child cohort study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.F.; Madsen, J.; Williams, S.L.; Browne, M.; Burke, K.J. Differential effects of intuitive and disordered eating on physical and psychological outcomes for women with young children. Matern. Child. Health J. 2022, 26, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, T.H.; Stone, J.C.; Sears, K.; Klugar, M.; Tufanaru, C.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Aromataris, E.; Munn, Z. The revised JBI critical appraisal tool for the assessment of risk of bias for randomized controlled trials. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canto, G.L.; Stefani, C.M.; Massignan, C. Risco de Viés em Revisões Sistemáticas: Guia Prático; Centro Brasileiro de Pesquisas Baseadas em Evidências—Cobe UFSC: Florianópolis, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, L.; Timmerman, G.M.; Kim, M.; Sterling, B. Relationships between body image and depressive symptoms during postpartum in ethnically diverse, low-income women. Women Health 2002, 36, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, D.S.; Dinallo, J.M.; Kirner, T.L. Determinants of pregnancy and postpartum depression: Prospective influences of depressive symptoms, body image satisfaction, and exercise behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 2008, 36, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, A.C.; Fingerhut, R. Examining relationships between body dissatisfaction, maladaptive perfectionism, and postpartum depression symptoms. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2013, 42, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.O.; Sterling, B.S.; Guy, S.; Mahometa, M.J. Cumulative poor psychosocial and behavioral health among low-income women at 6 weeks postpartum. Nurs. Res. 2013, 62, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.O.; Xie, B.; Hendrickson, S.G.; Sterling, B.S. Behavioral and psychosocial health of new mothers and associations with contextual factors and perceived health. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2016, 45, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawed-Wessel, S.; Herbenick, D.; Schick, V. The relationship between body image, female genital self-image, and sexual function among first-time mothers. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2017, 43, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, R.F.; O’Flynn, J.L.; Bourdeau, A.; Zimmerman, E. A biopsychosocial model of body image, disordered eating, and breastfeeding among postpartum women. Appetite 2018, 126, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlaff, R.A.; Baruth, M.; Laframboise, F.C.; Deere, S.J. Examining the impact of body satisfaction and physical activity change on postpartum depressive symptoms. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Fischer, L.E.; Zimmerman, E. Partner influences, breastfeeding, and body image and eating concerns: An expanded biopsychosocial model. Appetite 2022, 169, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhteh, A.; Salari, N.; Jaberghaderi, N.; Khosrorad, T. Investigating the relationship between self-compassion and body image with postpartum depression in women referring to health centres in Iran. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2023, 28, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.T.; Dai, F.T. Weight retention predictors for Taiwanese women at six-month postpartum. J. Nurs. Res. 2007, 15, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shloim, N.; Rudolf, M.; Feltbower, R.G.; Blundell-Birtill, P.; Hetherington, M. Israeli and British women’s well-being and eating behaviours in pregnancy and postpartum. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2019, 37, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.K.; Heinberg, L.J.; Altabe, M.; Tantleff-Dunn, S. Exacting Beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, B.; Walenista, W.; Kamionka, A.; Lizińczyk, S.; Ptak, M. Connections Between Perceived Social Support and the Body Image in the Group of Women With Diastasis Recti Abdominis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 707775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siqueira, M.R.d.; Limongi, T.M.; Salzer, E.B.; Bomtempo, A.P.D.; Meireles, J.F.F.; Neves, C.M. Postpartum Women’s Body Dissatisfaction: A Systematic Review of Theoretical Models and Regression Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091463

Siqueira MRd, Limongi TM, Salzer EB, Bomtempo APD, Meireles JFF, Neves CM. Postpartum Women’s Body Dissatisfaction: A Systematic Review of Theoretical Models and Regression Analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091463

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiqueira, Marcela Rodrigues de, Tuany Mageste Limongi, Eduardo Borba Salzer, Ana Paula Delgado Bomtempo, Juliana Fernandes Filgueiras Meireles, and Clara Mockdece Neves. 2025. "Postpartum Women’s Body Dissatisfaction: A Systematic Review of Theoretical Models and Regression Analyses" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091463

APA StyleSiqueira, M. R. d., Limongi, T. M., Salzer, E. B., Bomtempo, A. P. D., Meireles, J. F. F., & Neves, C. M. (2025). Postpartum Women’s Body Dissatisfaction: A Systematic Review of Theoretical Models and Regression Analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091463