Users’ Perspectives on Primary Care and Public Health Services in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study with Implications for Healthcare Quality Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

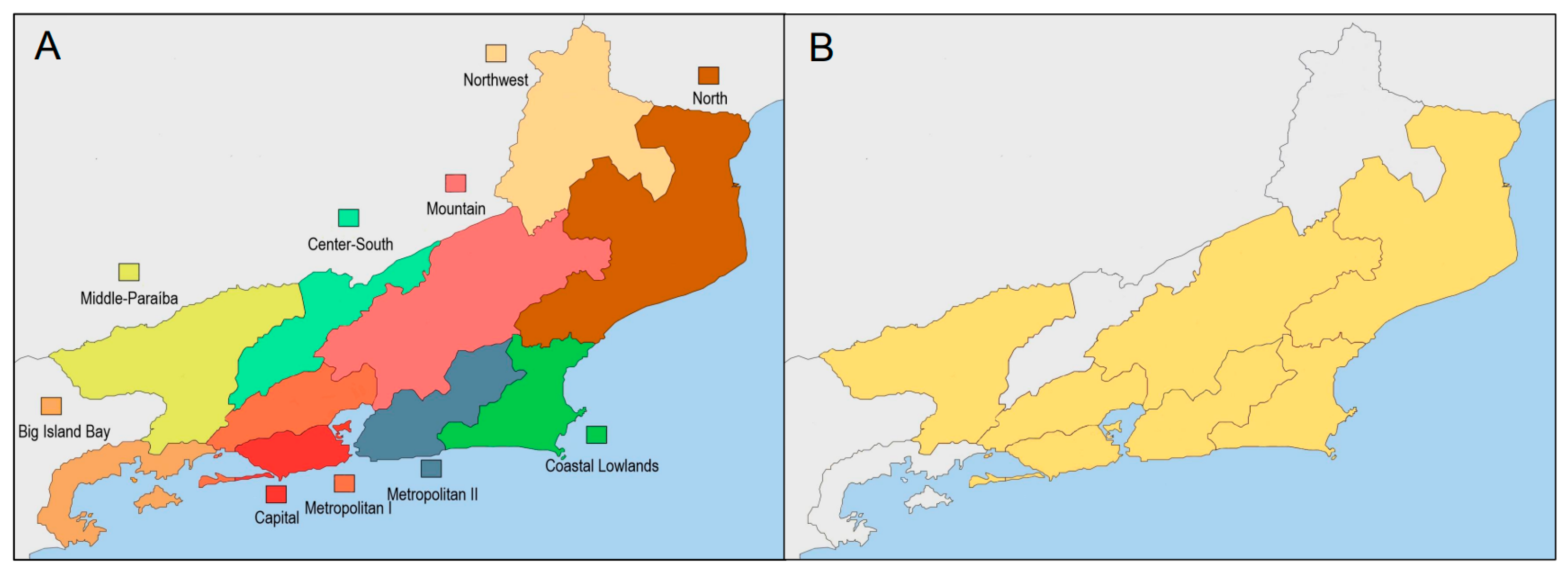

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Data Collection Instrument

2.3. Data Collection and Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

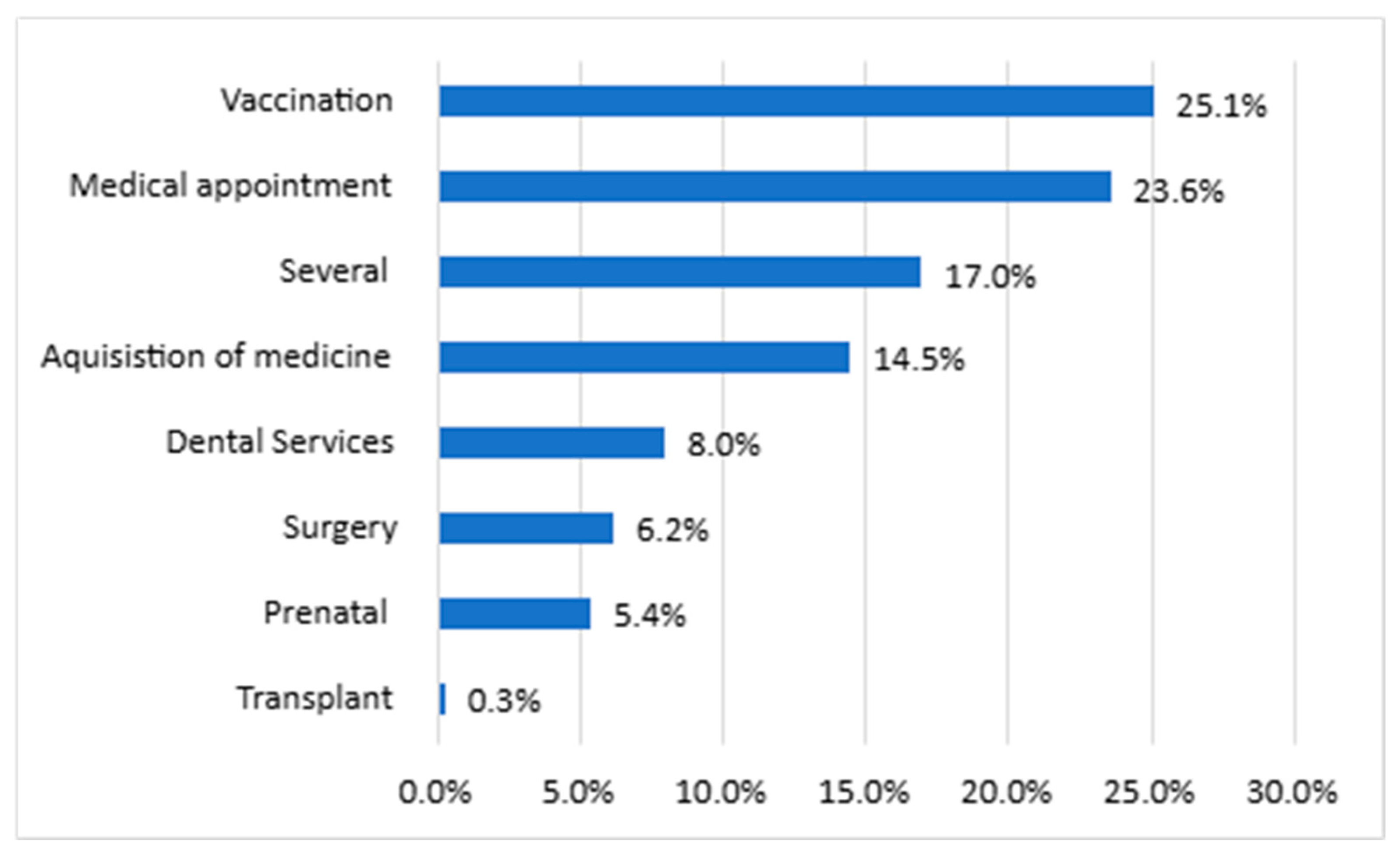

3.2. Responses from SUS Users

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Brasil. Lei nº 8.080, de 19 de Setembro de 1990. Dispõe Sobre as Condições Para a Promoção, Proteção e Recuperação da Saúde, a Organização e o Funcionamento dos Serviços Correspondentes e dá Outras Providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 20 September 1990. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8080.htm (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Brasil. Lei nº 8.142, de 28 de Dezembro de 1990. Dispõe Sobre a Participação da Comunidade na Gestão do Sistema Único de Saúde (sus) e Sobre as Transferências Intergovernamentais de Recursos Financeiros na Área da Saúde e dá Outras Providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 31 December 1990. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8142.htm (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD Reviews of Health Systems: Brazil 2021; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-reviews-of-health-systems-brazil-2021_146d0dea-en.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Physis. Regionalização em Saúde no Brasil: Uma Análise da Percepção dos Gestores de Comissões Intergestores Regionais. Physis Rev. Saúde Coletiva 2022, 32, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde. Portaria nº 4.279, de 30 de Dezembro de 2010. Estabelece Diretrizes Para a Organização da Rede de Atenção à Saúde no Âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde (sus); Diário Oficial da União, Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Elidio, G.A.; Sallas, J.; Pacheco, F.C.; de Oliveira, C.; Guilhem, D.B. Atenção primária à saúde: A maior aliada na resposta à epidemia da dengue no Brasil. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2024, 48, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousquat, A.; Akerman, M.; Mendes, A.; Louvison, M.; Frazão, P.; Narvai, P.C. Pandemia de covid-19: O SUS mais necessário do que nunca. Revista USP 2021, 1, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Política Nacional de Atenção Básica; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2017. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/politica_nacional_atencao_basica_2017.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Ministério da Saúde. Estratégia e-Multi: Equipes Multiprofissionais na Atenção Primária à Saúde; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2022.

- Peixoto, R.T.; Campos, M.R.; Luiza, V.L.; Mendes, L.V. O farmacêutico na Atenção Primária à Saúde no Brasil: Análise comparativa 2014-2017. Saúde Debate 2022, 46, 358–375. Available online: https://revista.saudeemdebate.org.br/sed/article/view/6410 (accessed on 17 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde. Agência Nacional de Saúde Suplementar. ANS Divulga Dados de Beneficiários Referentes a Agosto de 2024. Brasília, Brazil. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.br/ans/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/numeros-do-setor/ans-divulga-dados-de-beneficiarios-referentes-a-agosto-de-2024 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Souza Júnior, P.R.B.; Szwarcwald, C.L.; Damacena, G.N.; Stopa, S.R.; Vieira, M.L.F.P.; Almeida, W.S.; Oliveira, M.M.; Sardinha, L.M.V.; Macário, E.M. Cobertura de plano de saúde no Brasil: Análise dos dados da Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde 2013 e 2019. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2021, 26, 2529–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Estudos para Políticas de Saúde. Estado do Rio Tem a pior Cobertura de Atenção Básica do sus no país; Piauí, a melhor: Veja o ranking. [S.l.: S.n.]. 2025. Available online: https://ieps.org.br/estado-do-rio-tem-a-pior-cobertura-de-atencao-basica-do-sus-no-pais-piaui-a-melhor-veja-o-ranking/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Economist Impact. The Road to Health Inclusivity: From Policy to Practice. 2023. Available online: https://impact.economist.com/projects/health-inclusivity-index/documents/the_road_to_health_inclusivity_health_inclusivity_index_2023_economist_impact_final.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Dornas, B.S.S.; Reis, E.A.; Campos, A.A.O.; Godói, I.P.D. Percepções sobre os serviços de saúde pública em macaé-rj: Um estudo transversal. Rev. Saúde Pública Paraná 2024, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.S.; Reis, E.A.; Godman, B.; Campbell, S.M.; Meyer, J.C.; Sena, L.W.P.; Godói, I.P.D. Users’ perceptions of access to and quality of unified health system services in brazil: A cross-sectional study and implications to healthcare management challenges. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimundo, M.C.; Reis, E.A.; Ferraz, I.F.L.; Borges de Almeida, C.P.; Godman, B.; Campbell, S.M.; Meyer, J.C.; Godói, I.P.D. Users’ perceptions of access to and quality of public health services in brazil: A cross-sectional study in metropolitan rio de janeiro, including pharmaceutical services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picorelli, L.F. o papel da participação comunitária no sus. Rev. Direito Med. 2019, 1, 1–20. Available online: https://www.mpgo.mp.br/portal/arquivos/2022/06/01/13_19_11_463_O_papel_da_participa_o_comunit_ria_no_SUS.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Caring for Canadians: Canada’s Future Health Workforce—The Canadian Health Workforce Education, Training and Distribution Study. 2025. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/health-human-resources/workforce-education-training-distribution-study.html (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- HS England. Working in Partnership with People and Communities: Statutory Guidance. London: NHS England, Updated 2023. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/working-in-partnership-with-people-and-communities-statutory-guidance/ (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Vital Strategies, Umane, Universidade Federal de Pelotas (UFPel), Resolve to Save Lives. More Data Better Health: Acesso e Percepção da População Brasileira Sobre a Atenção Primária à Saúde, Módulo 1. São Paulo, Brazil. 2025. Available online: https://www.vitalstrategies.org (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Gadelha, C.A.; Costa, K.S.; Nascimento, J.M., Jr.; Soeiro, O.M.; Mengue, S.S.; Motta, M.L.; Carvalho, A.C. PNAUM: Integrated approach to pharmaceutical services, science, technology and innovation. Rev. Saude Publica 2016, 50 (Suppl. 2), 3s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardousi, N.; Nunes da Silva, E.; Kovacs, R.; Borghi, J.; Barreto, J.O.; Kristensen, S.R.; Sampaio, J.; Shimizu, H.E.; Gomes, L.B.; Russo, L.X.; et al. Performance bonuses and the quality of primary health care delivered by family health teams in brazil: A difference-in-differences analysis. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1004033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengue, S.S.; Bertoldi, A.D.; Boing, A.C.; Tavares, N.U.L.; Pizzol, T.D.S.D.; Oliveira, M.A.; Arrais, P.S.D.; Ramos, L.R.; Farias, M.R.; Luiza, V.L.; et al. National survey on access, use and promotion of rational use of medicines (PNAUM): Household survey component methods. Rev. Saude Publica 2016, 50 (Suppl. 2), 4s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, L.A.F.; Tonini, T.; Sousa da Silva, A.; Dutt-Ross, S.; de Souza Velasque, L. Evaluation of primary health care units in the Rio de Janeiro city according to results of pmaq 2012. J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2017, 40, S71–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protasio, A.P.L.; Gomes, L.B.; Machado, L.D.S.; Valença, A.M.G. User satisfaction with primary health care by region in Brazil: 1st cycle of external evaluation from PMAQ-AB. Satisfação do usuário da Atenção Básica em Saúde por regiões do Brasil: 1º ciclo de avaliação externa do PMAQ-AB. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2017, 22, 1829–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protasio, A.P.; Gomes, L.B.; Machado, L.D.; Valença, A.M. Factors associated with user satisfaction regarding treatment offered in Brazilian primary health care. Cad. Saúde Publica 2017, 33, e00184715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, T.M.; Valerio, F.R.; Silva, M.F.B.; Santos, P.L.; Tenório, B.A.; Branco, S.M.C.; Pereira, M.F.; Sá, A.S.; Costa, N.K.A.; Soares, L.C.L.; et al. Desafios da universalidade no sus: Avaliação do acesso e qualidade dos serviços de saúde no brasil. Cad. Pedag. 2024, 21, e5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UMANE. Estudo Inédito Revela Percepção Sobre Acesso e Qualidade da Atenção primária à Saúde. Available online: https://biblioteca.observatoriosaudepublica.com.br/blog/saude-publica-no-brasil-atencao-primaria/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Vital Strategies, UMANE, Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Instituto Devive, Resolve to Save Lives. Mais Dados Mais saúde–Atenção Primária à Saúde. Brasil. 2025. ISBN 978-65-85591-09-6. Available online: https://pesquisa.atlasintel.org (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Campos, D.S. Saúde e políticas sociais no rio de janeiro brasil: História, caminhos e tendências. Cad. Saúde Pública 2019, 35, e00065119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Censo Demográfico Brasileiro de 2022. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. 2022. Available online: https://censo2022.ibge.gov.br/panorama/ (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Diagnóstico de saúde da região metropolitana I; Secretaria de Saúde: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Diagnóstico de saúde da região metropolitana II; Secretaria de Saúde: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Diagnóstico de saúde da região norte; Secretaria de Saúde: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Diagnóstico de saúde da região baixada litorânea; Secretaria de Saúde: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Diagnóstico de saúde da região médio paraíba; Secretaria de Saúde: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Governo do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Diagnóstico de saúde da região serrana; Secretaria de Saúde: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Althubaiti, A. Sample size determination: A practical guide for health researchers. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2022, 24, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. Histórico de Cotação; Banco Central do Brasil: Brasília, Brazil, 2025. Available online: https://www.bcb.gov.br/estabilidadefinanceira/historicocotacoes (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde 2019: Informações Sobre Domicílios, Acesso e Utilização dos Serviços de Saúde. IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv101748.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Cantalino, J.L.R.; Scherer, M.D.D.A.; Soratto, J.; Schäfer, A.A.; Anjos, D.S.O.D. Satisfação dos usuários em relação aos serviços de Atenção Primária à Saúde no Brasil. Rev. Saúde Pública 2021, 55, 22. Available online: https://revistas.usp.br/rsp/article/view/186498 (accessed on 17 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- São Paulo (Estado). Secretaria de Estado da Saúde. Pesquisa de Satisfação dos Usuários do sus/sp. São Paulo, Brazil. 2023. Available online: https://fedap.com.br/2023/09/12/governo-de-sp-lanca-pesquisa-de-satisfacao-dos-usuarios-do-sus-paulista/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Matta, S.R.; Bertoldi, A.D.; Emmerick, I.C.M.; Fontanella, A.T.; Costa, K.S.; Luiza, V.L. Fontes de obtenção de medicamentos por pacientes diagnosticados com doenças crônicas, usuários do Sistema Único de Saúde. Cad. Saúde Pública 2018, 34, e00073817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.A.; Luiza, V.L.; Tavares, N.U.L.; Mengue, S.S.; Arrais, P.S.D.; Farias, M.R.; Pizzol, T.D.S.D.; Ramos, L.R.; Bertoldi, A.D. Access to medicines for chronic diseases in Brazil: A multidimensional approach. Rev. Saude Publica 2016, 50 (Suppl. 2), 6s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, M.G.C.; Sampaio, J.P.S.; Dourado, C.S.M.E. Percepção Da População Sobre O Papel Do Farmacêutico No Contexto Da Pandemia Do Novo Coronavírus. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e54310918304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, L.N.; Campbell, S.M.; Amaral, I.B.S.T.; Reis, R.S.; Godman, B.; Meyer, J.C.; Godói, I.P.D. Public health financing in Brazil (2019–2022): An analysis of the national health fund and implications for health management. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1568351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agência Nacional de Saúde Suplementar (ANS). Dados Econômico-Financeiros do Setor de Planos de Saúde: 1º Trimestre de 2025. Brasília, Brazil. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.br/ans (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Mahmood, S.; Sequeira, R.; Siddiqui, M.M.U.; Herkenhoff, M.B.A.; Ferreira, P.P.; Fernandes, A.C.; Sousa, P. Decentralization of the health system-experiences from Pakistan, Portugal and Brazil. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2024, 22, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.T.; Franco, T.A.V.; Pitthan, R.G.V.; Cabral, L.M.S.; Cotrim, D.F.; Gomes, B.C. Saúde pública e comunicação: Impasses do SUS à luz da formação democrática da opinião pública. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2022, 27, 1547–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil. Lei nº 10.741, de 1º de Outubro de 2003. Dispõe Sobre o Estatuto da Pessoa Idosa e dá Outras Providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, Brazil, 1 October 2003. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/2003/l10.741.htm (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Secretaria de Saúde do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. População Residente Estudo de Estimativas Populacionais por Município, Idade e Sexo 2000–2024-Pactuada pela SES-RJ. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. 2024. Available online: https://sistemas.saude.rj.gov.br/tabnetbd/dhx.exe?populacao/pop_populacao_ripsa2024.def (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde 2019: Atenção Primária à Saúde e Informações Antropométricas; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020; Available online: https://www.pns.icict.fiocruz.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/liv101758.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Novais, M.; Martins, C.B. Perfil dos Beneficiários de Planos e SUS e o Acesso a Serviços de Saúde–PNAD 2003 e 2008. Instituto de Estudos de Saúde Suplementar-IESS. 2010. Available online: https://www.iess.org.br/sites/default/files/2021-04/TD35.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Ahmed, S.K. Research Methodology Simplified: How to Choose the Right Sampling Technique and Determine the Appropriate Sample Size for Research. Oral Oncol. Rep. 2024, 12, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulley, S.B.; Cummings, S.R.; Browner, W.S.; Grady, D.G.; Newman, T.B. Delineando a Pesquisa clínica: Uma Abordagem Epidemiológica, 4th ed.; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, A.C. Métodos e Técnicas de Pesquisa Social, 7th ed.; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, R.; Ranganathan, P. Study designs: Part 2-Descriptive studies. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2019, 10, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | n | (%) * |

|---|---|---|

| Gender * | ||

| Female | 659 | 66.2% |

| Male | 337 | 33.8% |

| Age Profile (years old) | ||

| 18–25 | 166 | 16.6% |

| 26–45 | 415 | 41.5% |

| 46–60 | 255 | 25.5% |

| More than 60 | 163 | 16.3% |

| Race/skin color ** | ||

| White | 385 | 39.4% |

| Black | 196 | 20.0% |

| Brown | 390 | 40.0% |

| Other | 6 | 0.6% |

| Education level *** | ||

| Never attended school | 15 | 1.5% |

| Incomplete elementary school | 141 | 14.5% |

| Completed elementary school | 72 | 7.4% |

| Incomplete high school | 56 | 5.7% |

| Completed high school | 390 | 40.0% |

| Incomplete college | 145 | 15% |

| Completed college or more | 156 | 16.0% |

| Family Income **** (Number of times the minimum wage *****) | ||

| Up to 1 | 161 | 18.4% |

| 1–2 | 221 | 26.0% |

| 2–3 | 216 | 25.4% |

| 3–5 | 264 | 19.3% |

| 5–10 | 72 | 8.5% |

| 10–20 | 14 | 1.6% |

| >20 | 3 | 0.4% |

| Use of SUS services—Yes | 927 | 93.6% |

| Has a private health plan—Yes | 314 | 31.7% |

| Relevance of SUS n (%) * | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Indispensable | Complementary | Indifferent | p-Value | ||

| Always | 364 (90.8%) | 29 (7.2%) | 8 (2.0%) | 0.056 | ||

| Frequently | 112 (86.2%) | 16 (12.3%) | 2 (1.5%) | |||

| Sometimes | 219 (85.9%) | 27 (10.%) | 9 (3.5%) | |||

| Rarely | 156 (82.1%) | 24 (12.6%) | 10 (5.3%) | |||

| ALL | 851 (87.2%) | 96 (9.8%) | 29 (3.0%) | |||

| Access to SUS Services n (%) ** | ||||||

| Frequency | Very Good | Good | Neither Good nor Bad | Bad | Very Bad | p-Value |

| Always | 32 (8.2%) | 159 (40.6%) | 125 (31.9%) | 54 (13.8%) | 22 (5.6%) | 0.002 |

| Frequently | 6 (4.8%) | 55 (44.0%) | 43 (34.4%) | 13 (10.4%) | 8 (6.4%) | |

| Sometimes | 10 (4.0%) | 68 (27.3%) | 97 (39.0%) | 55 (22.1%) | 19 (7.6%) | |

| Rarely | 10 (7.6%) | 48 (36.4%) | 38 (28.8%) | 24 (18.2%) | 12 (9.1%) | |

| Never | 1 (2.2%) | 10 (21.7%) | 22 (47.8%) | 8 (17.4%) | 5 (10.9%) | |

| ALL | 59 (6.3%) | 340 (36.0%) | 325 (34.4%) | 154 (16.3%) | 66 (7.0%) | |

| Quality of SUS Services n (%) *** | ||||||

| Frequency | Very Good/Good | Neither Good nor Bad | Bad/Very Bad | p-Value | ||

| Always | 196 (48.6%) | 135 (33.5%) | 72 (17.9%) | 0.003 | ||

| Frequently | 66 (50.8%) | 49 (37.7%) | 15 (11.5%) | |||

| Sometimes | 92 (36.7%) | 103 (41.0%) | 56 (22.3%) | |||

| Rarely/Never | 65 (35.7%) | 73 (40.1%) | 44 (24.2%) | |||

| ALL | 419 (43.4%) | 360 (37.3%) | 187 (19.4%) | |||

| Access to SUS Services n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Income (Number of Times the Minimum Wage) | Very Good/Good | Nor Good nor Bad | Bad/Very Bad | p-Value |

| Up to 1 | 88 (56.0%) | 35 (22.3%) | 34 (21.7%) | 0.001 |

| 1–2 | 80 (37.7%) | 76 (35.8%) | 56 (26.4%) | |

| 2–3 | 85 (42.1%) | 70 (34.6%) | 47 (23.3%) | |

| 3–4 | 53 (34.2%) | 62 (40.0%) | 40 (25.8%) | |

| >4 | 28 (33.3%) | 39 (46.4%) | 17 (20.3%) | |

| TOTAL * | 334 (41.2%) | 282 (34.8%) | 194 (24.0%) | |

| Quality of SUS Services n (%) | ||||

| Family Income (Number of Times the Minimum Wage) | Very Good/Good | Nor Good nor Bad | Bad/Very Bad | p-Value |

| Up to 1 | 85 (53.5%) | 49 (30.8%) | 25 (15.7%) | 0.164 |

| 1–2 | 90 (41.5%) | 80 (36.9%) | 47 (21.6%) | |

| 2–3 | 87 (41.0%) | 84 (39.6%) | 41 (19.3%) | |

| 3–4 | 62 (39.5%) | 63 (40.1%) | 32 (20.4%) | |

| >4 | 29 (34.9%) | 38 (45.8%) | 16 (19.3%) | |

| TOTAL ** | 353 (42.6%) | 35 (37.9%) | 161 (19.5%) | |

| Questions | Answers % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Always | Frequently | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | Total | |

| When you pick up medications at public pharmacies of the SUS, do the staff who dispense the medications provide information and/or guidance on how to use them? * | 146 (29.8%) | 107 (21.9%) | 67 (13.7%) | 38 (7.8%) | 131 (26.8%) | 489 (100.0%) |

| When picking up medications at public pharmacies of the SUS, do you receive guidance on how to store them at home? ** | 68 (14.0%) | 45 (9.2%) | 64 (13.2%) | 48 (9.9%) | 261 (53.7%) | 486 (100.0%) |

| Is the pharmacist or another staff member at public pharmacies of the SUS available when you need to ask questions about medications? *** | 170 (40.1%) | 87 (20.5%) | 82 (19.3%) | 25 (5.9%) | 60 (14.2%) | 424 (100.0%) |

| Have you ever encountered a pharmacist at the public facility you visit (ESF, UBS, or medication dispensing unit)? **** | 61 (15.7%) | 76 (19.6%) | 57 (14.7%) | 32 (8.2%) | 162 (41.8%) | 388 (100.0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferraz, I.F.L.; Raimundo, M.C.; Barros, N.M.A.M.; Souza, J.S.; Lucio, B.M.V.; Tenreiro, T.P.; Reis, E.A.; de Souza Serio dos Santos, D.M.; Chaves, L.A.; Godman, B.; et al. Users’ Perspectives on Primary Care and Public Health Services in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study with Implications for Healthcare Quality Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091424

Ferraz IFL, Raimundo MC, Barros NMAM, Souza JS, Lucio BMV, Tenreiro TP, Reis EA, de Souza Serio dos Santos DM, Chaves LA, Godman B, et al. Users’ Perspectives on Primary Care and Public Health Services in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study with Implications for Healthcare Quality Assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091424

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerraz, Igor F. L., Mariana C. Raimundo, Natalia M. A. M. Barros, Jhoyce S. Souza, Barbará M. V. Lucio, Thiago P. Tenreiro, Edna A. Reis, Danielle Maria de Souza Serio dos Santos, Luisa A. Chaves, Brian Godman, and et al. 2025. "Users’ Perspectives on Primary Care and Public Health Services in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study with Implications for Healthcare Quality Assessment" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091424

APA StyleFerraz, I. F. L., Raimundo, M. C., Barros, N. M. A. M., Souza, J. S., Lucio, B. M. V., Tenreiro, T. P., Reis, E. A., de Souza Serio dos Santos, D. M., Chaves, L. A., Godman, B., Campbell, S. M., Meyer, J. C., & Godói, I. P. D. (2025). Users’ Perspectives on Primary Care and Public Health Services in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: A Cross-Sectional Study with Implications for Healthcare Quality Assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091424

_Garrett.png)