Impact of Combined Hypertension and Diabetes on the Prevalence of Disability in Brazilian Older People—Evidence from Population Studies in 2013 and 2019

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

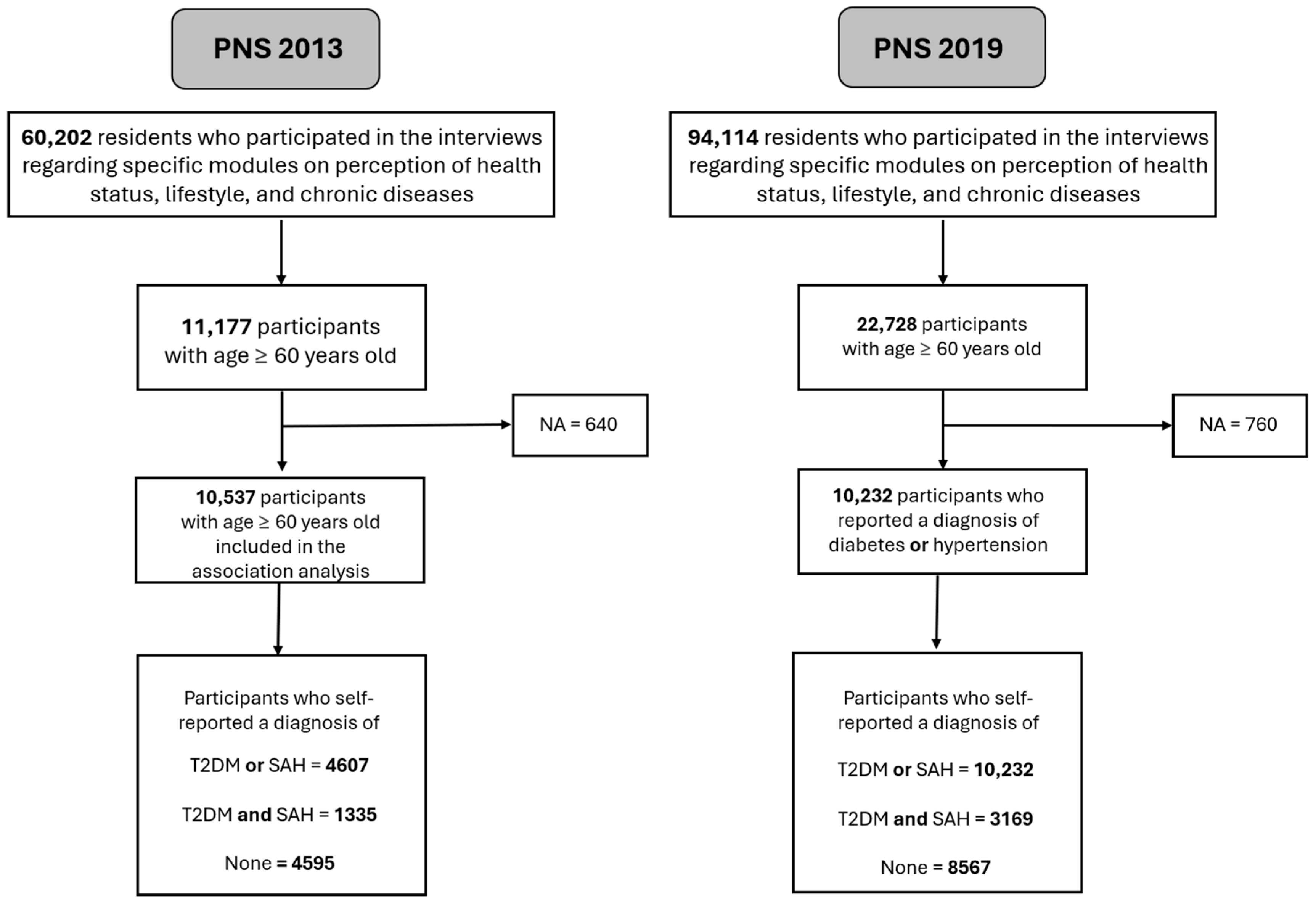

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Brazilian National Health Survey (2013 PNS) Sample Description

3.3. Brazilian National Health Survey (PNS 2019) Sample Description

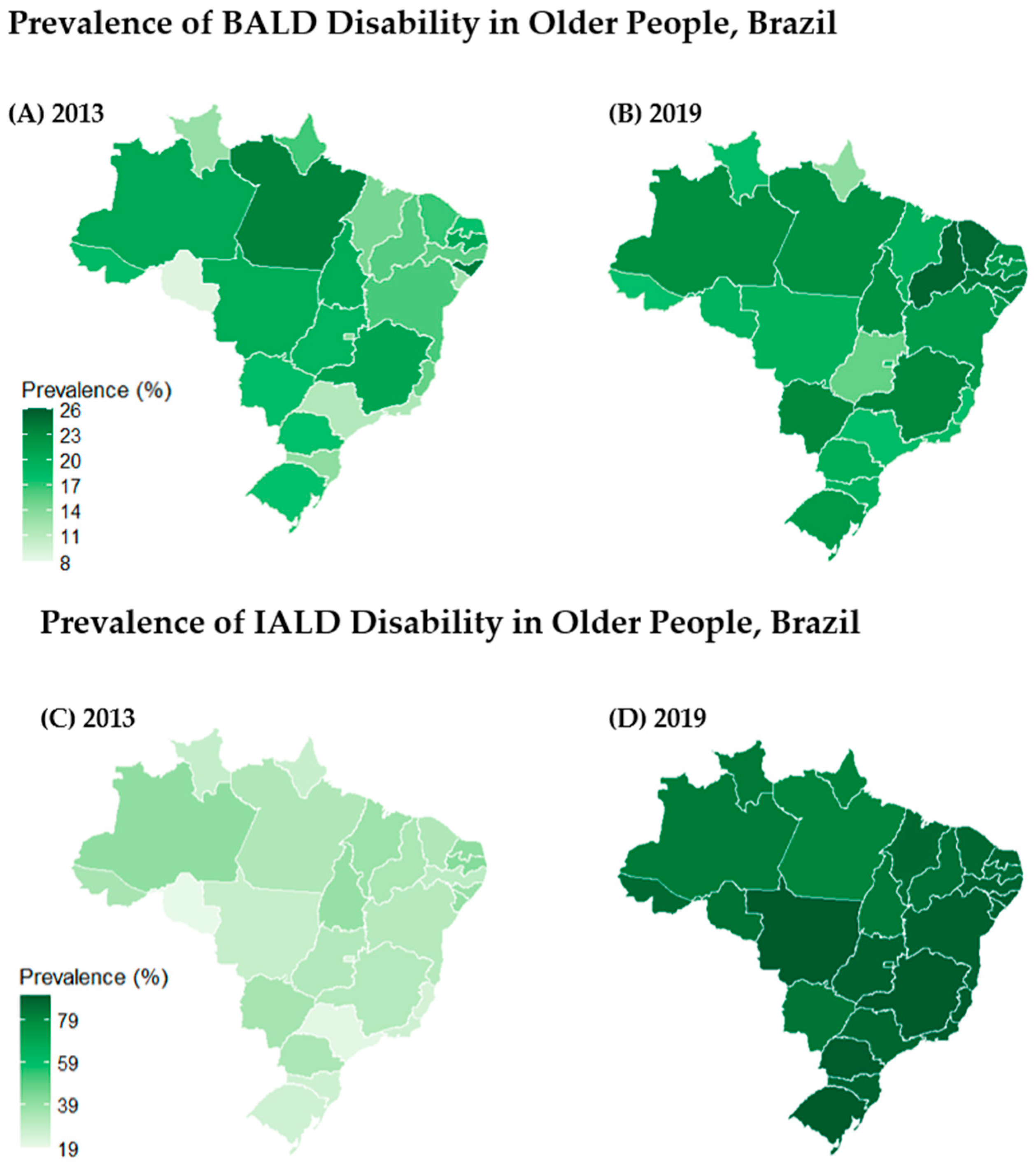

3.4. Disability Prevalences

3.5. Association Between T2DM/SAH and BADL/IADL

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 95%CI | 95% Confidence Interval |

| BADL | Basic Activities of Daily Living |

| DALY | Disability-Adjusted Life Years |

| GBD | Global Burden of Disease |

| IADL | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living |

| IBGE | Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística |

| NCDs | Chronic noncommunicable diseases |

| NHS | National Health Survey |

| PNS | Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde |

| PRa | Prevalence-Ratio-Adjusted (ou conforme sua definição específica) |

| Pw | Probability weight |

| SAH | Systemic Arterial Hypertension |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

Appendix A

| Variable | Definitions in the Original Study | New Categorizations |

|---|---|---|

| Age | In years | In years |

| Sex | Male | Masculine |

| Female | Feminine | |

| Education | Uneducated | Incomplete elementary education |

| Incomplete elementary school | ||

| Complete elementary | Completed elementary education | |

| Incomplete medium | ||

| Complete medium | ||

| Incomplete higher education | ||

| Completed higher education | ||

| Race | White | White |

| Yellow | Black | |

| Brown | Others | |

| Black | ||

| Indigenous | ||

| Region | Rural | Rural |

| Urban | Urban | |

| Marital status | Married | Married |

| Divorced | Not married | |

| Separate | ||

| Single | ||

| Widower | ||

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | Self-reported medical diagnosis | 0—does not have diabetes |

| 1—has diabetes | ||

| Systemic Arterial Hypertension | Self-reported medical diagnosis | 0—no hypertension |

| 1—has hypertension | ||

| No difficulty | 0—cannot, has much difficulty, and has little difficulty | |

| There is little difficulty | ||

| It has great difficulty | 1—No difficulty | |

| Cannot | ||

| IADL | No difficulty | 0—Cannot, has much difficulty, and has little difficulty |

| There is little difficulty | ||

| It has great difficulty | 1—No difficulty | |

| Cannot |

| Item No. | STROBE Recommendation | Location in the Manuscript (Page, Paragraph) |

|---|---|---|

| 1(a) | Indicate the study’s design with a commonly used term in the title or the abstract | Title (p. 1, 1) |

| 1(b) | Provide in the abstract an informative and balanced summary of what was carried out and what was found | Abstract (p. 1,1) |

| 2 | Explain the scientific background and rationale for the investigation being reported | Introduction (p. 1, 1–4) |

| 3 | State-specific objectives, including any prespecified hypotheses | Final of the introduction (p. 2, 4) |

| 4 | Present key elements of the study design early in the paper | Materials and Methods (p. 2, 1–2) |

| 5 | Describe the setting, locations, and relevant dates, including periods of recruitment, exposure, follow-up, and data collection | Materials and Methods (p. 3, 3) |

| 6(a) | Give the eligibility criteria, and the sources and methods of selection of participants | Materials and Methods (p. 3, 4) |

| 7 | Clearly define all outcomes, exposures, predictors, potential confounders, and effect modifiers. Give diagnostic criteria, if applicable | Materials and Methods (p. 3, 4–6) |

| 8 | For each variable of interest, give sources of data and details of methods of assessment (measurement). Describe the comparability of assessment methods if there is more than one group | Materials and Methods (p. 3, 5–6) |

| 9 | Describe any efforts to address potential sources of bias | Does not apply |

| 10 | Explain how the study size was arrived at | Materials and Methods (p. 2, 2) |

| 11 | Explain how quantitative variables were handled in the analyses. If applicable, describe which groupings were chosen and why | Materials and Methods (p. 3, 5–6) |

| 12(a) | Describe all statistical methods, including those used to control for confounding | Materials and Methods (p. 3, 7) |

| 12(b) | Describe any methods used to examine subgroups and interactions | Does not apply |

| 12(c) | Explain how missing data were addressed | Materials and Methods (p. 3, 5) |

| 12(d) | If applicable, describe analytical methods taking account of sampling strategy | Materials and Methods (p. 2, 7) |

| 12(e) | Describe any sensitivity analyses | Does not apply |

| 13(a) | Report numbers of individuals at each stage of study (e.g., potentially eligible, examined for eligibility, included, analyzed) | Results (p. 4, 1) |

| 13(b) | Give reasons for non-participation at each stage | Results (p. 4, 1) |

| 13(c) | Consider use of a flow diagram | Results (p. 4, 1) |

| 14(a) | Give characteristics of study participants (e.g., demographic, clinical, and social) and information on exposures and potential confounders | Results (p. 6 and 8) |

| 14(b) | Indicate number of participants with missing data for each variable of interest | Results (p. 6 and 8) |

| 15 | Report numbers of outcome events or summary measures | Results (p. 6 and 8) |

| 16(a) | Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates and their precision (e.g., 95% confidence interval). Make clear which confounders were adjusted for and why they were included | Results (3 and Table 4) |

| 16(b) | Report category boundaries when continuous variables were categorized | Methods (p. 3, 4) |

| 16(c) | If relevant, consider translating estimates of relative risk into absolute risk for a meaningful time period | Does not apply |

| 17 | Report other analyses completed, e.g., subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses | Does not apply |

| 18 | Summarise key results with reference to study objectives | Discussion (p. 13) |

| 19 | Discuss limitations of the study, taking into account sources of potential bias or imprecision | Discussion (p. 13, 4–5) |

| 20 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results considering objectives, limitations, multiplicity of analyses, results from similar studies, and other relevant evidence | Discussion and conclusions (p. 13, 5–6; p. 14, 4) |

| 21 | Discuss the generalizability (external validity) of the study results | Conclusions (p. 14, 1) |

| 22 | Give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study | p. 15, 2 |

| Categories | K001 To Eat | K004 To Bath | K007 Bathroom Use | K010 To Dress Up | K013 To Walk | K016 + K019 Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No difficulty | 10,667 (95.44) | 10,469 (93.67%) | 10,536 (94.27%) | 10,239 (91.61%) | 10,290 (92.06%) | 20,573 (92.03) |

| There is little difficulty | 316 (2.83) | 354 (3.17) | 352 (3.15) | 551 (4.93) | 522 (4.67) | 1161 (5.19) |

| It has great difficulty | 125 (1.12%) | 180 (1.61%) | 139 (1.24%) | 215 (1.92%) | 222 (1.99%) | 360 (1.61%) |

| Cannot | 69 (0.62%) | 174 (1.56%) | 150 (1.34%) | 172 (1.54%) | 143 (1.28%) | 260 (1.16%) |

| Categories | K022 Shopping | K025 Finances | K028 Medicines | K031 Doctor | K034 Transport |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No difficulty | 9302 (83.22%) | 9891 (88.49%) | 8211 (73.46%) | 8646 (77.36%) | 8732 (78.12%) |

| There is little difficulty | 678 (6.07%) | 478 (4.28%) | 391 (3.50%) | 1151 (10.30%) | 921 (8.24%) |

| It has great difficulty | 457 (4.09%) | 263 (2.35%) | 205 (1.83%) | 630 (5.64%) | 639 (5.72%) |

| Cannot | 740 (6.62%) | 545 (4.88%) | 245 (2.19%) | 750 (6.71%) | 885 (7.92%) |

| Does not use medication | - | - | 2125 (19.01%) | - | - |

| Categories | K001 To Eat | K004 To Bath | K007 Bathroom Use | K010 To Dress Up | K013 To Walk | K016 + K019 Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No difficulty | 21,613 (95.09%) | 21,061 (92.67%) | 20,681 (90.99%) | 20,052 (88.23%) | 20,289 (89.27%) | 39,898 (87.77%) |

| There is little difficulty | 697 (3.07%) | 936 (4.12%) | 1086 (4.78%) | 1749 (7.70%) | 1405 (6.18%) | 3576 (7.87%) |

| It has great difficulty | 250 (1.10%) | 374 (1.65%) | 372 (1.64%) | 590 (2.60%) | 517 (2.27%) | 1.015 (2.23%) |

| Cannot | 168 (0.74%) | 357 (1.57%) | 589 (2.59%) | 337 (1.48%) | 517 (2.27%) | 967 (2.13%) |

| Categories | K022 Shopping | K025 Finances | K028 Remedy | K031 Doctor | K034 Transport |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No difficulty | 18,473 (81.28%) | 19,722 (86.77%) | 602 (2.65%) | 16,956 (74.60%) | 16,916 (74.43%) |

| There is little difficulty | 1768 (7.78%) | 1293 (5.69%) | 482 (2.12%) | 2578 (11.34%) | 2383 (10.48%) |

| It has great difficulty | 963 (4.24%) | 607 (2.67%) | 1295 (5.70%) | 1226 (5.39%) | 1367 (6.01%) |

| Cannot | 1524 (6.71%) | 1106 (4.87%) | 16896 (74.34%) | 1968 (8.66%) | 2062 (9.07%) |

| Does not use medication | - | - | 3453 (15.19%) | - | - |

References

- GBD Compare. Available online: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, G.M.M.D.; Brant, L.C.C.; Polanczyk, C.A.; Malta, D.C.; Biolo, A.; Nascimento, B.R.; Souza, M.D.F.M.D.; Lorenzo, A.R.D.; Fagundes Júnior, A.A.D.P.; Schaan, B.D.; et al. Cardiovascular Statistics—Brazil 2023. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2024, 121, e20240079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzy, J.; Campos, M.R.; Emmerick, I.; Silva, R.S.D.; Schramm, J.M.D.A. Prevalência de diabetes mellitus e suas complicações e caracterização das lacunas na atenção à saúde a partir da triangulação de pesquisas. Cad. Saúde Pública 2021, 37, e00076120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde, 2019: Ciclos de Vida; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde: 2019: Percepção do Estado de Saúde, Estilos de Vida, Doenças Crônicas e Saúde Bucal: Brasil e Grandes Regiões; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; McAlister, F.A.; Walker, R.L.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Campbell, N.R.C. Cardiovascular Outcomes in Framingham Participants with Diabetes: The Importance of Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2011, 57, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.H.; Chuang, L.L.; Lee, Y.J.; Chiu, C.J. How Does Diabetes Accelerate Normal Aging? An Examination of ADL, IADL, and Mobility Disability in Middle-aged and Older Adults with and Without Diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 182, 109114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, E.; Backholer, K.; Gearon, E.; Harding, J.; Freak-Poli, R.; Stevenson, C.; Peeters, A. Diabetes and risk of physical disability in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013, 1, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.; Ren, X. Association between comorbid conditions and BADL/IADL disability in hypertension patients over age 45: Based on the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Medicine 2016, 95, e4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis Júnior, W.M.; Ferreira, L.N.; Molina-Bastos, C.G.; Bispo Júnior, J.P.; Reis, H.F.T.; Goulart, B.N.G. Prevalence of functional dependence and chronic diseases in the community-dwelling Brazilian older adults: An analysis by dependence severity and multimorbidity pattern. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damacena, G.N.; Szwarcwald, C.L.; Malta, D.C.; Souza Júnior, P.R.B.d.; Vieira, M.L.F.P.; Pereira, C.A.; Neto, O.L.d.M.; Júnior, J.B.d.S. O processo de desenvolvimento da Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde no Brasil, 2013. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2015, 24, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza Júnior, P.R.B.D.; Szwarcwald, C.L.; Almeida, W.D.S.D.; Damacena, G.N.; Pedroso, M.D.M.; Sousa, C.A.M.D.; Morais, I.D.S.; Saldanha, R.D.F.; Lima, J.; Stopa, S.R. Comparison of sampling designs from the two editions of the Brazilian National Health Survey, 2013 and 2019. Cad. Saúde Pública 2022, 38, e00164321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwarcwald, C.L.; Malta, D.C.; Pereira, C.A.; Vieira, M.L.F.P.; Conde, W.L.; Souza Júnior, P.R.B.D.; Damacena, G.N.; Azevedo, L.O.; Azevedo e Silva, G.; Theme, M.; et al. Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde no Brasil: Concepção e metodologia de aplicação. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2014, 19, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stopa, S.R.; Szwarcwald, C.L.; Oliveira, M.M.D.; Gouvea, E.D.C.D.P.; Vieira, M.L.F.P.; Freitas, M.P.S.D. National Health Survey 2019: History, methods and perspectives. Epidemiol. Serv. Saúde 2020, 29, e2020315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrivankova, V.W.; Richmond, R.C.; Woolf, B.A.R.; Yarmolinsky, J.; Davies, N.M.; Swanson, S.A.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Higgins, J.P.; Timpson, N.J.; Dimou, N.; et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Using Mendelian Randomization: The STROBE-MR Statement. JAMA 2021, 326, 1614–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, S. Assessing self-maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1983, 31, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, B.M. International Measurement of Disability; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brefka, S.; Dallmeier, D.; Mühlbauer, V.; von Arnim, C.A.F.; Bollig, C.; Onder, G.; Petrovic, M.; Schönfeldt-Lecuona, C.; Seibert, M.; Torbahn, G.; et al. A Proposal for the Retrospective Identification and Categorization of Older People with Functional Impairments in Scientific Studies-Recommendations of the Medication and Quality of Life in Frail Older Persons (MedQoL) Research Group. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2019, 20, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowers, J.R. Diabetes mellitus and vascular disease. Hypertension 2013, 61, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.C.; Leite, I.d.C.; Machado, C.J. Factors associated with functional disability of elderly in Brazil: A multilevel analysis. Rev. Saúde Pública 2010, 44, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.D.; Saes, M.D.O.; Nunes, B.P.; Siqueira, F.C.V.; Soares, D.C.; Fassa, M.E.G.; Thumé, E.; Facchini, L.A. Functional disability indicators and associated factors in the elderly: A population-based study in Bagé, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Epidemiol. Serv. Saude 2017, 26, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavasso, W.C.; Beltrame, V. Functional capacity and reported morbidities: A comparative analysis in the elderly. Rev. Bras. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2017, 20, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, G.M.; Mambrini, J.V.d.M.; Lima-Costa, M.F.; Peixoto, S.V. Perfil de multimorbidade associado à incapacidade entre idosos residentes na Região Metropolitana de Belo Horizonte, Brasil. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2019, 24, 1853–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, B.M.; Silva, P.O.; Vieira, M.A.; Costa, F.M.d.; Carneiro, J.A. Evaluation of functional disability and associated factors in the elderly. Rev. Bras. Geriatr. Gerontol. 2019, 22, e180163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.P.; Wagner, K.J.P.; Schneider, I.J.C.; Danielewicz, A.L. Padrões de multimorbidade e incapacidade funcional em idosos brasileiros: Estudo transversal com dados da Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00241619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, B.R.; Almeida, J.M.d.; Barbosa, M.R.; Rossi-Barbosa, L.A.R. Avaliação da capacidade funcional dos idosos e fatores associados à incapacidade. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2014, 19, 3317–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lestari, S.K.; Ng, N.; Kowal, P.; Santosa, A. Diversity in the Factors Associated with ADL-Related Disability among Older People in Six Middle-Income Countries: A Cross-Country Comparison. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlop, D.D.; Manheim, L.M.; Sohn, M.W.; Liu, X.; Chang, R.W. Incidence of functional limitation in older adults: The impact of gender, race, and chronic conditions. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002, 83, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, L.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Qin, W.; Ding, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xie, S.; Yu, Z. Chronic Disease, Disability, Psychological Distress and Suicide Ideation among Rural Elderly: Results from a Population Survey in Shandong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyewole, O.O.; Ale, A.O.; Ogunlana, M.O.; Gurayah, T. Burden of disability in type 2 diabetes mellitus and the moderating effects of physical activity. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 3128–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolde, J.; Beaney, T.; Carnagarin, R.; Stergiou, G.S.; Poulter, N.R.; Schutte, A.E.; Schlaich, M.P. Regional variation of age-related blood pressure trajectories and their association with blood pressure control rates, disability-adjusted life years and death. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45 (Suppl. S1), ehae666.2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buford, T.W. Hypertension and aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 26, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.J.; Wray, L.A. Physical disability trajectories in older Americans with and without diabetes: The role of age, gender, race or ethnicity, and education. Gerontologist 2011, 51, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Causal associations of frailty and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Medicine 2025, 104, e41630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malta, D.C.; Duncan, B.B.; Schmidt, M.I.; Machado, Í.E.; Silva, A.G.D.; Bernal, R.T.I.; Pereira, C.A.; Damacena, G.N.; Stopa, S.R.; Rosenfeld, L.G.; et al. Prevalência de diabetes mellitus determinada pela hemoglobina glicada na população adulta brasileira, Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde. Rev bras epidemiol. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2019, 22 (Suppl. S2), E190006. [Google Scholar]

- Picon, R.V.; Fuchs, F.D.; Moreira, L.B.; Fuchs, S.C. Prevalence of hypertension among elderly persons in urban Brazil: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Am. J. Hypertens. 2013, 26, 541–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghs, M.; Atkin, K.; Graham, H.; Hatton, C.; Thomas, C. Implications for public health research of models and theories of disability: A scoping study and evidence synthesis. Public Health Res. 2016, 4, 1–166. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK378941/ (accessed on 6 July 2025). [CrossRef]

| 2013 PNS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALD | IADL | ||||||

| Variable | Total Population | Independent | Moderate | Severe | Independent | Moderate | Severe |

| n = 11,177 | n = 9424 | n = 1197 | n = 556 | n = 7893 | n = 1540 | n = 1744 | |

| Chronic Disease | |||||||

| Diabetes or Hypertension | 4607 (44.3) | 3794 (43.6) | 567 (48.1) | 246 (47.7) | 3091 (42.9) | 677 (46.8) | 839 (48.5) |

| Both | 1335 (13.6) | 1021 (12.2) | 208 (20.6) | 106 (21.6) | 786 (15.7) | 242 (15.7) | 307 (18.8) |

| None | 4595 (42.1) | 4055 (44.2) | 366 (31.3) | 174 (30.6) | 3543 (18.8) | 536 (37.4) | 516 (32.7) |

| NA | 640 | 554 | 56 | 30 | 473 | 85 | 82 |

| Age | |||||||

| 60–69 | 6238 (56.6) | 5590 (60.2) | 512 (44.0) | 136 (22.5) | 5148 (66.2) | 618 (39.5) | 472 (25.6) |

| 70–79 | 3441 (29.8) | 2859 (29.3) | 391 (32.2) | 191 (34.3) | 2220 (27.0) | 631 (40.4) | 590 (34.2) |

| 80–89 | 1293 (11.6) | 877 (9.2) | 243 (19.6) | 173 (32.9) | 494 (6.3) | 261 (17.9) | 538 (30.8) |

| 90+ | 205 (2.0) | 98 (1.3) | 51 (4.2) | 56 (10.3) | 31 (0.5) | 30 (2.2) | 144 (9.4) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 6622 (56.4) | 5508 (55.7) | 754 (57.9) | 360 (63.6) | 4421 (53.8) | 993 (59.0) | 1208 (66.3) |

| Male | 4555 (43.6) | 3916 (44.3) | 443 (42.1) | 196 (36.4) | 3472 (46.2) | 574 (41.0) | 536 (33.7) |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 5314 (53.8) | 4477 (53.9) | 569 (53.3) | 268 (52.0) | 3816 (54.5) | 696 (53.4) | 802 (50.5) |

| Black | 5701 (44.8) | 4807 (44.5) | 615 (46.2) | 279 (47.1) | 3957 (43.8) | 822 (45.5) | 822 (48.7) |

| Others | 160 (1.4) | 139 (1.6) | 12 (0.5) | 9 (1.0) | 119 (1.7) | 21 (1.1) | 20 (0.7) |

| NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Marital Status | |||||||

| With partner | 4808 (53.5) | 4207 (55.4) | 444 (48.9) | 753 (32.7) | 3725 (58.0) | 553 (45.6) | 350 (39.0) |

| Without partner | 6369 (46.5) | 5217 (44.6) | 157 (51.1) | 399 (67.3) | 4168 (42.0) | 987 (54.4) | 1214 (61.0) |

| Education level | |||||||

| Until elementary school | 7738 (70.7) | 6337 (68.4) | 953 (82.2) | 448 (84.2) | 4997 (64.6) | 1,26 (84.4) | 1481 (87.3) |

| High school or more | 3439 (29.3) | 3087 (31.6) | 244 (17.8) | 108 (84.2) | 2896 (35.4) | 280 (15.6) | 263 (12.7) |

| Region | |||||||

| Urban | 8999 (085.2) | 7575 (85.5) | 953 (81.2) | 471 (87.3) | 6401 (86.2) | 1211 (82.8) | 1387 (82.5) |

| Rural | 2178 (14.8) | 1849 (14.5) | 244 (18.8) | 85 (12.7) | 1492 (13.8) | 329 (17.2) | 357 (82.5) |

| 2019 PNS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALD | IADL | ||||||

| Variable | Total Population | Independent | Moderate | Severe | Independent | Moderate | Severe |

| n = 22,728 | n = 18,141 | n = 3040 | n = 1547 | n = 2967 | n = 14,354 | n = 5407 | |

| Chronic Disease | |||||||

| Diabetes or Hypertension | 10,232 (47.5) | 8053 (47.0) | 1470 (51.4) | 709 (45.0) | 326 (13.0) | 7193 (52.1) | 2713 (51.5) |

| Both | 3169 (15.2) | 2176 (13.3) | 628 (20.8) | 365 (26.2) | 37 (1.2) | 1988 (15.3) | 1144 (21.8) |

| None | 8567 (37.3) | 7283 (39.7) | 853 (27.7) | 431 (28.8) | 2324 (85.8) | 4827 (32.6) | 1416 (26.7) |

| NA | 760 | 629 | 89 | 42 | 280 | 346 | 134 |

| Age | |||||||

| 60–69 | 12,555 (56.3) | 10,756 (60.7) | 1345 (44.9) | 454 (28.7) | 2154 (74.0) | 8788 (62.6) | 1613 (29.7) |

| 70–79 | 7157 (30.1) | 5584 (29.3) | 1091 (35.2) | 482 (29.5) | 692 (21.8) | 4469 (30.0) | 1996(34.8) |

| 80–89 | 2580 (11.5) | 1652 (9.2) | 508 (16.8) | 420 (27.2) | 115 (3.9) | 1036 (7.1) | 1429 (27.6) |

| 90+ | 436 (2.1) | 149 (0.8) | 96 (3.1) | 191 (14.6) | 6 (0.3) | 61 (0.3) | 369 (7.9) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 12,535 (56.7) | 9654 (54.6) | 1918 (64.5) | 963 (64.6) | 9654 (54.6) | 1918 (64.5) | 963 (64.6) |

| Male | 10,193 (43.3) | 8487 (45.4) | 1122 (35.5) | 584 (35.4) | 8487 (45.4) | 1122 (35.5) | 584 (35.4) |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 9901 (50.5) | 7948 (50.9) | 1287 (48.0) | 666 (50.7) | 1155 (48.5) | 6544 (52.0) | 2202 (47.5) |

| Black | 12,456 (47.7) | 9890 (47.1) | 1709 (50.9) | 857 (47.6) | 1755 (49.2) | 7562 (46.1) | 3139 (51.1) |

| Others | 369 (1.8) | 301 (1.9) | 44 (1.2) | 24 (1.7) | 56 (2.2) | 247 (1.9) | 66 (1.3) |

| NA | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Marital Status | |||||||

| With partner | 9946 (50.7) | 8221 (52.6) | 1233 (45.8) | 492 (37.5) | 1433 (55.4) | 6726 (54.3) | 1787 (38.2) |

| Without partner | 12,782 (49.3) | 9920 (47.4) | 1807 (54.2) | 1055 (62.5) | 1534 (44.6) | 7628 (45.7) | 3620 (61.8) |

| Education level | |||||||

| Until elementary school | 14,987 (63.3) | 11,445 (59.6) | 2307 (76.5) | 1235 (79.1) | 1929 (58.6) | 8612 (57.6) | 4446 (81.4) |

| High school or more | 7741 (36.7) | 6696 (40.4) | 733 (23.5) | 312 (20.9) | 1038 (41.4) | 5742 (42.4) | 961 (18.6) |

| Region | |||||||

| Urban | 17,313 (85.5) | 13,750 (85.4) | 2361 (86.2) | 1202 (84.7) | 2066 (81.6) | 11,228 (87.3) | 4019 (82.5) |

| Rural | 5415 (14.5) | 4391 (14.6) | 679 (13.8) | 345 (15.3) | 901 (18.4) | 3126 (12.7) | 1388 (17.5) |

| BALD | 2013 PNS | 2019 PNS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Moderate | Severe | Moderate | Severe | ||||

| PrAdj (CI 95%) | p Value | PrAdj (CI95%) | p Value | PrAdj (CI 95%) | p Value | PrAdj (CI95%) | p Value | |

| Chronic Disease | ||||||||

| Only one | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Both | 1.39 (1.01–1.91) | 0.04 | 1.45 (0.85–2.47) | 0.16 | 1.20 (1.07–1.36) | <0.001 | 1.82 (1.59–2.07) | <0.001 |

| None | 0.70 (0.58–0.85) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.51–1.11) | 0.15 | 0.75 (0.66–0.84) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.82–1.04) | 0.20 |

| Elementary vs. High school or more | 1.64 (1.29–2.11) | <0.001 | 1.63 (1.15–4.02) | 0.005 | 1.72 (1.56–1.91) | <0.001 | 1.52 (1.32–1.74) | <0.001 |

| Female vs. Male | 0.97 (0.80–1.18) | 0.82 | 1.01 (0.65–1.56) | 0.95 | 1.29 (1.19–1.40) | <0.001 | 1.08(0.95–1.24) | 0.21 |

| Not married vs. married | 1.05 (0.85–1.30) | 0.60 | 1.73(1.06–2.83) | 0.02 | 1.00 (0.91–1.09) | 0.94 | 1.27 (1.11–1.45) | <0.001 |

| Urban vs. rural | 0.77 (0.62–0.95) | 0.01 | 1.11 (0.70–1.76) | 0.63 | 1.15 (1.14–1.45) | 0.01 | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) | 0.54 |

| Age (in years) | ||||||||

| 60–69 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 70–79 | 1.27 (1.03–1.57) | 0.02 | 2.53 (1.59–4.02) | <0.001 | 1.28 (0.89–0.90) | <0.001 | 1.69 (1.46–1.96) | <0.001 |

| 80–89 | 1.99 (1.58–2.52) | <0.001 | 5.63 (3.36–9.43) | <0.001 | 1.58 (1.39–1.79) | <0.001 | 3.84 (3.26–4.53) | <0.001 |

| 90+ | 2.47 (1.78–3.43) | <0.001 | 10.41 (6.68–16.21) | <0.001 | 1.56 (1.22–1.99) | <0.001 | 11.1 (9.64–12.8) | <0.001 |

| IADL | PNS 2013 | PNS 2019 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Moderate | Severe | Moderate | Severe | ||||

| PrAdj (95%CI) | p Value | PrAdj (95%CI) | p Value | PrAdj (95%CI) | p Value | PrAdj (95%CI) | p Value | |

| Chronic Disease | ||||||||

| Only one | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Both | 1.03 (0.83–1.28) | 0.73 | 1.23 (1.05–1.44) | 0.008 | 0.92 (0.91–0.93) | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.23–1.34) | <0.001 |

| None | 0.89 (0.75–1.05) | 0.18 | 0.79 (0.69–0.90) | 0.006 | 0.76 (0.75–0.77) | <0.001 | 0.77 (0.73–0.81) | <0.001 |

| Female vs. Male | 0.97 (0.82–1.14) | 0.71 | 1.32 (1.14–1.53) | <0.001 | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.27–1.42) | <0.001 |

| Urban vs. Rural | 0.96 (0.79–1.16) | 0.69 | 0.89 (0.79–1.00) | 0.055 | 1.08 (1.07–1.10) | <0.001 | 0.87(0.84–0.90) | <0.001 |

| Elementary vs. High school or more | 2.00 (1.64–2.44) | <0.001 | 2.04 (1.77–2.37) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.85–0.86) | <0.001 | 1.82 (1.71–1.94) | <0.001 |

| Not married vs. married | 1.32 (1.10–1.60) | 0.003 | 1.22(1.06–1.41) | 0.005 | 0.93 (0.92–0.94) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.14–1.26) | <0.001 |

| Black race | 0.92 (0.79–1.08) | 0.22 | 1.14 (1.00–1.29) | 0.04 | 0.95 (0.94–0.96) | <0.001 | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) | <0.001 |

| Other races | 0.79 (0.54–0.1.15) | 0.35 | 0.65 (0.45–0.92) | 0.01 | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | 0.24 | 0.73 (0.58–0.98) | 0.04 |

| Age (in years) | ||||||||

| 60–69 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 70–79 | 1.71 (1.42–2.07) | <0.001 | 2.28 (1.91–2.72) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.88–0.90) | <0.001 | 1.88 (1.76–2.00) | <0.001 |

| 80–89 | 1.88 (1.52–2.32) | <0.001 | 5.07 (4.33–5.94) | <0.001 | 0.57 (0.55–0.59) | <0.001 | 3.69 (3.47–3.92) | <0.001 |

| 90+ | 1.34 (0.75–2.39) | 0.30 | 8.52 (7.36–9.87) | <0.001 | 0.12 (0.10–0.15) | <0.001 | 5.65 (5.32–6.00) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro-Lucas, R.G.; Goulart, B.N.G.d.; Ziegelmann, P.K. Impact of Combined Hypertension and Diabetes on the Prevalence of Disability in Brazilian Older People—Evidence from Population Studies in 2013 and 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071157

Ribeiro-Lucas RG, Goulart BNGd, Ziegelmann PK. Impact of Combined Hypertension and Diabetes on the Prevalence of Disability in Brazilian Older People—Evidence from Population Studies in 2013 and 2019. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071157

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro-Lucas, Rafaela Gonçalves, Barbara Niegia Garcia de Goulart, and Patricia Klarmann Ziegelmann. 2025. "Impact of Combined Hypertension and Diabetes on the Prevalence of Disability in Brazilian Older People—Evidence from Population Studies in 2013 and 2019" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071157

APA StyleRibeiro-Lucas, R. G., Goulart, B. N. G. d., & Ziegelmann, P. K. (2025). Impact of Combined Hypertension and Diabetes on the Prevalence of Disability in Brazilian Older People—Evidence from Population Studies in 2013 and 2019. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071157