Psychological Dimensions of Professional Burnout in Special Education: A Cross-Sectional Behavioral Data Analysis of Emotional Exhaustion, Personal Achievement, and Depersonalization

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Three Dimensions of Burnout

1.2. Risk Factors in Special Education Settings

1.3. International Perspectives and Research Gap

1.4. Contemporary Challenges in Special Education

1.5. The Greek Context and Study Rationale

1.6. Scope of the Research

1.7. Research Questions

- [RQ1] What are the levels at which the dimensions of burnout are observed in the sample? This question seeks to establish baseline prevalence rates for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal achievement among special education professionals, providing foundational descriptive data for the target population.

- [RQ2] What is the degree of correlation between the three dimensions of burnout and demographic factors? This investigation examines the relationships between burnout dimensions and key demographic variables, including gender, age, teaching experience, educational background, and workplace characteristics, to identify at-risk populations and protective factors.

- [RQ3] What is the degree of impact of the three dimensions of burnout on the psychological burden of the individual due to the recent health crisis? This question examines how pre-existing burnout dimensions affect educators’ psychological responses to contemporary health-related stressors, exploring burnout as a vulnerability factor.

- [RQ4] What is the degree of impact of psychological burden due to the health crisis as a function of all three dimensions of burnout? This inquiry investigates the combined predictive power of all three burnout dimensions in explaining variance in psychological burden related to health crises, examining the cumulative and interactive effects of the burnout syndrome on contemporary stress responses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Purpose

2.2. Participants and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

2.4. Instrumentation

2.4.1. Demographic Questionnaire

2.4.2. Maslach Burnout Inventory–Educators Survey (MBI-ES)

2.4.3. Scoring and Interpretation

2.4.4. Reliability and Validity

2.5. Data Analysis

- For RQ1 (burnout levels): Descriptive statistics included means, standard deviations, minimum and maximum values, and frequency distributions. Numerical and ordinal variables were analyzed using means, standard deviations, and bar charts, while categorical variables were examined through frequency tables, percentage bar charts, and pie charts.

- For RQ2 (demographic correlations): Inferential analyses employed Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient to examine relationships between numerical and ordinal variables. This addressed the relationships between burnout dimensions and demographic factors.

- For RQ3 and RQ4 (COVID-19 impact): Simple linear regression was utilized to assess the impact of burnout dimensions on psychological burden related to the health crisis. The internal consistency of the three burnout subscales was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, with values greater than 0.70 indicating satisfactory reliability.

2.5.1. Additional Statistical Procedures

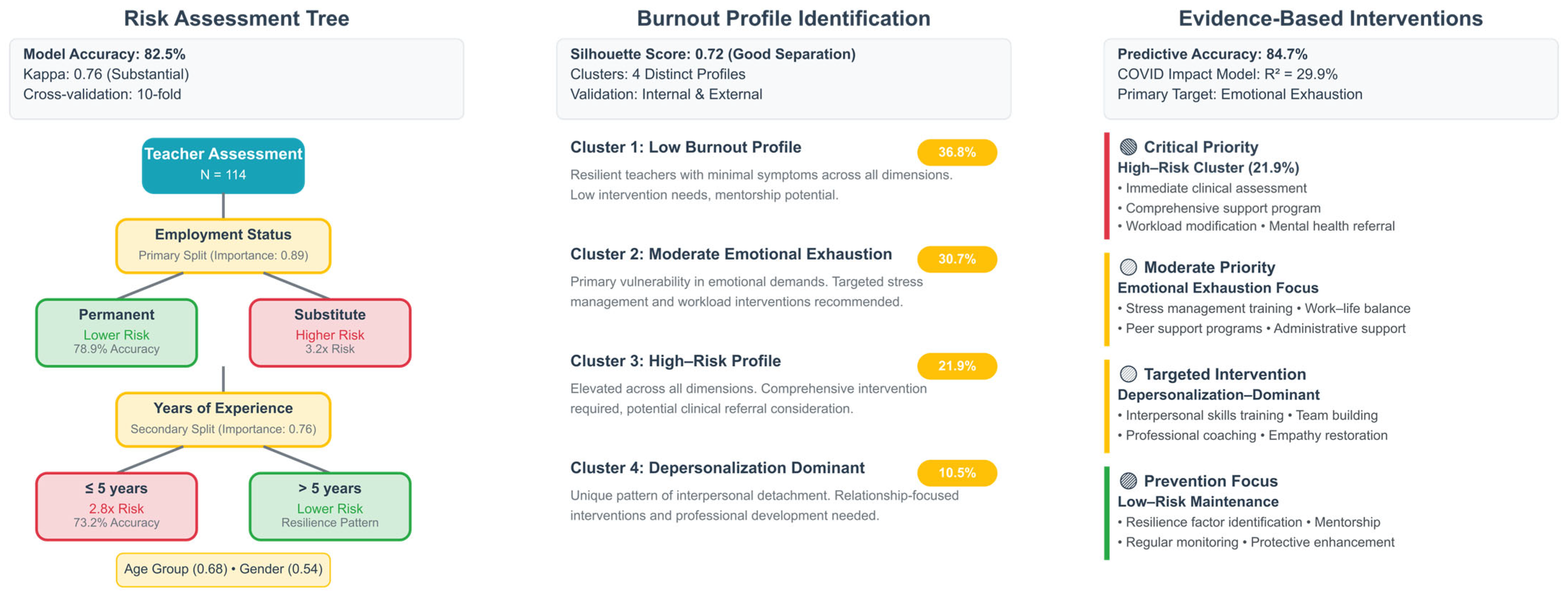

- Cluster Analysis: K-means clustering was performed to identify distinct burnout profiles using the three burnout dimensions as input variables. The optimal number of clusters was determined through the elbow method and silhouette analysis.

- Classification Analysis: Decision tree analysis using the CART algorithm identified demographic and workplace factors that predict burnout risk. This approach provided clear decision rules for identifying at-risk teachers.

- Advanced Regression Techniques: To examine potential non-linear relationships between burnout dimensions and COVID-19 psychological impact, multiple modeling approaches were compared.

2.5.2. Missing Data and Assumptions

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Burnout Inventory Analysis

3.2.1. Emotional Exhaustion

3.2.2. Personal Achievement

3.2.3. Depersonalization

3.2.4. Overall Burnout Profile

3.3. Statistical Analysis (RQ2: Demographic Relationships)

3.3.1. Comprehensive Correlation Analysis

3.3.2. Demographic Group Comparisons

3.3.3. Employment Status and School Type Analysis

3.3.4. Multiple Regression Analysis

3.4. COVID-19 Health Crisis Impact (RQ3 & RQ4)

3.4.1. Correlation Analysis (RQ3: Individual Burnout Dimensions)

3.4.2. Regression Analysis (RQ4: Combined Effect)

3.5. Institutional Framework Stress

3.6. Advanced Statistical Analyses

3.6.1. Clustering Analysis of Burnout Profiles

3.6.2. Classification Tree Analysis

3.6.3. Association Rule Mining

3.6.4. Predictive Modeling for COVID-19 Impact

3.6.5. Anomaly Detection Analysis

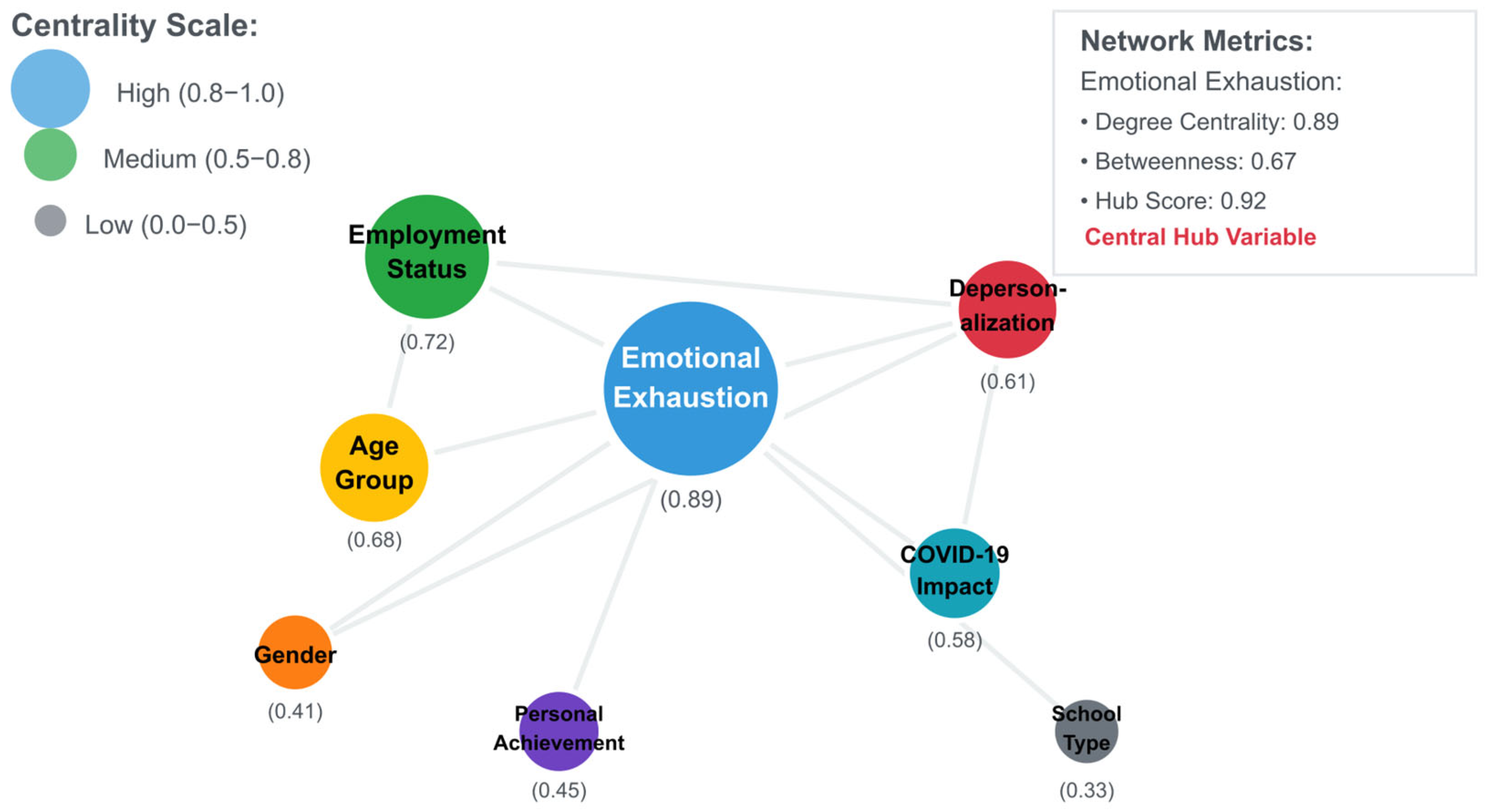

3.6.6. Network Analysis of Variable Relationships

3.6.7. Temporal Pattern Analysis

3.7. Summary of Key Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings and Theoretical Contributions

- Empathic Fatigue: Special education teachers engage in intensive emotional labor, constantly regulating their emotions while managing students with complex behavioral and emotional needs. This continuous empathic engagement depletes emotional resources faster than they can be replenished, creating a primary pathway to exhaustion.

- Autonomy Constraints: The highly regulated nature of special education, with mandated individualized education plans and bureaucratic requirements, potentially restricts teachers’ professional autonomy. This lack of control over work conditions may amplify emotional depletion.

- Resource Depletion Cascade: The pattern of correlations indicates that emotional exhaustion triggers a cascade effect—as emotional resources deplete, teachers have less capacity to maintain positive interpersonal relationships (leading to depersonalization) and achieve professional goals (reducing personal achievement).

4.2. Balanced Analysis of the Three Burnout Dimensions

4.2.1. Emotional Exhaustion: The Depletion of Emotional Resources

4.2.2. Personal Achievement: The Sustaining Force of Professional Efficacy

4.2.3. Depersonalization: The Interpersonal Dimension of Burnout

4.2.4. Dimensional Interactions and Systemic Patterns

- Emotional exhaustion is most sensitive to workload, administrative burden, and crisis frequency;

- Personal achievement responds to professional development opportunities, recognition systems, and clear progress indicators;

- Depersonalization is influenced by team cohesion, supervision quality, and the school’s relational climate.

4.3. Methodological Innovations and Clinical Applications

- Non-Linear Relationships: The improved predictive accuracy of advanced models suggests that burnout’s relationship with external stressors is more complex than traditional linear models assume, potentially involving threshold effects where emotional exhaustion must reach a critical level before cascading to other dimensions.

- Interaction Effects: Results indicate that the combination of being male AND a substitute teacher creates exponentially higher risk than either factor alone. This supports intersectionality theory in occupational health, suggesting that multiple vulnerability factors interact multiplicatively rather than additively [49].

- Temporal Dynamics: Career-stage patterns suggest a non-linear trajectory of burnout development, with the steepest risk during years 0–2, gradual improvement in years 3–7, and accelerated resilience development after year 8. This challenges linear career development models and suggests critical windows for intervention.

4.4. COVID-19 Impact and Contemporary Relevance

4.5. Demographic Insights and Policy Implications

- Gender Role Conflict: In Greece, as in many Mediterranean cultures, teaching—particularly special education—is predominantly viewed as a feminine profession. Male teachers may experience role conflict between societal expectations of masculinity and the nurturing demands of special education, potentially leading to emotional withdrawal as a coping mechanism.

- Emotional Expression Norms: Cultural norms discouraging emotional expression in men might prevent male teachers from seeking support or processing work-related stress healthily, leading to increased depersonalization as a maladaptive coping strategy.

- Career Choice Pressures: Male teachers in our sample possibly faced different career choice pressures, with some potentially entering teaching as a “fallback” career, which research suggests correlates with higher burnout risk.

4.6. Advanced Analysis as a Clinical Tool

- Feature Importance Rankings: Results indicate that emotional exhaustion, employment status, and age group form a hierarchical risk structure, suggesting a tiered intervention approach targeting these factors sequentially.

- Decision Rules: Clear demographic patterns provide actionable screening criteria that could be implemented in routine occupational health assessments.

- Network Centrality: The central role of emotional exhaustion suggests that interventions targeting this dimension would have maximum systemic impact—a finding that could prioritize resource allocation in constrained educational budgets.

4.7. Implications for Special Education Practice

4.8. Limitations and Methodological Considerations

4.9. Future Research Directions and Clinical Implications

4.10. Clinical and Policy Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scott, L.A.; Bettini, E.; Brunsting, N. Special education teachers of color burnout, working conditions, and recommendations for EBD research. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2023, 31, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, G.; Yuan, C.; Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, R. What causes burnout in special school physical education teachers? Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, B.; Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Burback, L.; Wei, Y. Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among teachers: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsting, N.C.; Cumming, M.M.; Garwood, J.D.; Urquiza, N. Special education teachers’ wellbeing and burnout. In Handbook of Research on Special Education Teacher Preparation; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2023; pp. 296–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benigno, V.; Usai, F.; Mutta, E.D.; Ferlino, L.; Passarelli, M. Burnout among special education teachers: Exploring the interplay between individual and contextual factors. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2025, 40, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsting, N.C.; Bettini, E.; Rock, M.L.; Royer, D.J.; Common, E.A.; Lane, K.L.; Xie, F.; Chen, A.; Zeng, F. Burnout of Special Educators Serving Students with Emotional-Behavioral Disorders: A Longitudinal Study. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2021, 43, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, M.M.; O’Brien, K.M.; Brunsting, N.C.; Bettini, E. Special educators’ working conditions, self-efficacy, and practices use with students with emotional/behavioral disorders. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2021, 42, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garwood, J.D. Special educator burnout and fidelity in implementing behavior support plans: A call to action. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2023, 31, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, A.F.; Sandilos, L.E.; Pilny, W.V.; Schwartz, S.; Wehby, J.H. Teaching students with emotional/behavioral disorders: Teachers’ burnout profiles and classroom management. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2022, 30, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, K.; Koslouski, J. The emotional job demands of special education: A qualitative study of alternatively certified novices’ emotional induction. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 2021, 44, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, W.A.; Carriere, D. Special education funding and teacher turnover. Educ. Econ. 2021, 29, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrew, J.; Ruble, L.; Cormier, C.J.; Dueber, D. Special educators’ mental health and burnout: A comparison of general and teacher specific risk factors. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2023, 132, 104209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodics, B.; Nagy, K.; Szenasi, S.; Varga, R.; Szabo, E. School demands and resources as predictors of student burnout among high school students. Sch. Ment. Health 2023, 15, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca-Pellicer, M.; Soto-Rubio, A.; Gil-Monte, P.R. Development of burnout syndrome in non-university teachers: Influence of demand and resource variables. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 644025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Sun, Z.; Liu, D.; Yin, H.; Shi, L. Factors associated with academic burnout and its prevalence among university students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela-Aro, K.; Tang, X.; Upadyaya, K. Study demands-resources model of student engagement and burnout. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfika, R.; Azzahra, W.; Ananda, Y.; Saifudin, I.M.M.Y.; Abdullah, K.L. Academic burnout among nursing students: The role of stress, depression, and anxiety within the Demand Control Model. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2025, 20, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, S.; Hietajärvi, L.; Salmela-Aro, K. School burnout trends and sociodemographic factors in Finland 2006–2019. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 1659–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.J.; Diamond, L.; McCartney, C.; Kwon, K.A. Early childhood special education teachers’ job burnout and psychological stress. Early Educ. Dev. 2022, 33, 1364–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruble, L.; McGrew, J.; Fischer, M.; Findley, J.; Stayton, R. School and intrapersonal predictors and stability of rural special education teacher burnout. Rural Spec. Educ. Q. 2023, 42, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, K.C.; Sebastian, J.; Eddy, C.L.; Reinke, W.M. School leadership, climate, and professional isolation as predictors of special education teachers’ stress and coping profiles. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2023, 31, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, U.; Aldrup, K.; Roloff, J.; Lüdtke, O.; Hamre, B.K. Does instructional quality mediate the link between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and student outcomes? A large-scale study using teacher and student reports. J. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 114, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. The interrelationship between emotional intelligence, self-efficacy, and burnout among foreign language teachers: A meta-analytic review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 913638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Chan, M.; Lin, X.; Chen, C. Teacher victimization and teacher burnout: Multilevel moderating role of school climate in a large-scale survey study. J. Sch. Violence 2022, 21, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, R.A.; Aldhahir, A.M.; Alqahtani, J.S.; Almarkhan, H.M.; Alghamdi, S.M.; Alqarni, A.A.; Alhotye, M.; Algarni, S.S.; Alahmadi, F.H.; Alahmari, M.A. Burnout and Resilience among Respiratory Therapy (RT) Students during Clinical Training in Saudi Arabia: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, S.C.; Mahatmya, D.; Bruhn, A.L. Educator burnout in the age of COVID-19: A mediation analysis of perceived stressors, work sense of coherence, and sociodemographic characteristics. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2024, 137, 104384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, A.I.; Lopes, J.; Oliveira, C. Teachers’ voices: A qualitative study on burnout in the Portuguese educational system. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Richter, E.; Kleickmann, T.; Richter, D. Class size affects preservice teachers’ physiological and psychological stress reactions: An experiment in a virtual reality classroom. Comput. Educ. 2022, 188, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučinić, V.; Stanimirović, D.; Gligorović, M.; Jablan, B.; Marinović, M. Stress and empathy in teachers at general and special education schools. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2022, 69, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmer, O.; Palomares, E.A.; Popa-Roch, M. Attitudes towards disability and burnout among teachers in inclusive schools in France. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2024, 71, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, C.; Murphy, M. Burnout in Irish teachers: Investigating the role of individual differences, work environment and coping factors. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2015, 50, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einav, M.; Confino, D.; Geva, N.; Margalit, M. Teachers’ Burnout—The Role of Social Support, Gratitude, Hope, Entitlement and Loneliness. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2024, 9, 827–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Support. Teacher Wellbeing Index 2022. London: Education Support. 2022. Available online: https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/media/zoga2r13/teacher-wellbeing-index-2022.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Sarıçam, H.; Sakız, H. Burnout and teacher self-efficacy among teachers working in special education institutions in Turkey. Educ. Stud. 2014, 40, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, H. An analysis of burnout and job satisfaction among Turkish special school headteachers and teachers, and the factors effecting their burnout and job satisfaction. Educ. Stud. 2004, 30, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Du, R. Psychological capital, mindfulness, and teacher burnout: Insights from Chinese EFL educators through structural equation modeling. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1351912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stathopoulou, A.; Spinou, D.; Driga, A.M. Burnout prevalence in special education teachers, and the positive role of ICTs. Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng. 2023, 19, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruble, L.; Cormier, C.J.; McGrew, J.; Dueber, D.M. A comparison of measurement of stability and predictors of special education burnout and work engagement. Remedial and Special Education. Adv. Online Publ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, Y. The research trend of big data in education and the impact of teacher psychology on educational development during COVID-19: A systematic review and future perspective. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 753388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Promoting Inclusive Education: Addressing Challenges in Legislation, Educational Policy and Practice. Brussels: DG REFORM. 2021. Available online: https://reform-support.ec.europa.eu/what-we-do/skills-education-and-training/promoting-inclusive-education-addressing-challenges-legislation-educational-policy-and-practice_en (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. Country policy Review: Greece. Brussels: European Agency. 2022. Available online: http://www.european-agency.org/sites/default/files/agency-projects/CPRA/Phase2/CPRA%20Greece.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Antoniou, A.S.; Pavlidou, K.; Charitaki, G.; Alevriadou, A. Profiles of teachers’ work engagement in special education: The impact of burnout and job satisfaction. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2024, 71, 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidou, K.; Alevriadou, A.; Antoniou, A.S. Professional burnout in general and special education teachers: The role of interpersonal coping strategies. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2022, 37, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitaki, G.; Kourti, I.; Gregory, J.L.; Ozturk, M.; Ismail, Z.; Alevriadou, A.; Soulis, S.-G.; Sakici, Ş.; Demirel, C. Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education: A Cross-National Exploration. Trends Psychol. 2022, 32, 1120–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law 4368/2016. Measures for Accelerating Government Work and Other Provisions. Greek Government Gazette, A 21/21.02.2016. Available online: https://natlex.ilo.org/dyn/natlex2/r/natlex/fe/details?p3_isn=104200&cs=17BRq8-NUVeQhysNPYHRBTVsNT0lJ6axN8is6jHzpyzuEKjTr56OOuJo21olopO4nlogu4B0FCVQ_nZW2a_k_Ag (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Law 4823/2021. Upgrading the School and Other Provisions. Greek Government Gazette, A 136/03.08.2021. Available online: https://www.kodiko.gr/nomothesia/document/739038/nomos-4823-2021 (accessed on 2 September 2025). (In Greek).

- Creswell, J.; Poth, C.N.; Rawlins, P. Mapping Design Trends and Evolving Directions Using the Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods Research Design. In The Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods Research Design; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023; pp. 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heus, P.D.; Diekstra, R.F.W. Do Teachers Burn Out More Easily? A Comparison of Teachers with Other Social Professions on Work Stress and Burnout Symptoms. Underst. Prev. Teach. Burn. 1999, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Schwab, R.L. Maslach Burnout Inventory-Educators Survey (MBI-ES). In Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, 3rd ed.; Maslach, C., Jackson, S.E., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinos, C.M. Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Educators Survey among elementary and secondary school teachers in Cyprus. Stress Health 2006, 22, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, R.P.; Horne, S.; Mitchell, G. Burnout in direct care staff in intellectual disability services: A factor analytic study of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2004, 48, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, B.K.; Fischer, D.G. The nature of burnout: A study of the three-factor model of burnout in human service and non-human service samples. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1993, 66, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Froidevaux, A.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Shi, J. Preretirement resources and postretirement life satisfaction change trajectory: Examining the mediating role of retiree experience during retirement transition phase. J. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 108, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, M.; Galvin, R.; Pettigrew, J. Becoming an academic retiree: A longitudinal study of women academics’ transition to retirement experiences from a university in the Republic of Ireland. J. Occup. Sci. 2023, 30, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cece, V.; Guillet-Descas, E.; Lentillon-Kaestner, V. The longitudinal trajectories of teacher burnout and vigour across the scholar year: The predictive role of emotional intelligence. Psychol. Sch. 2022, 59, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masdonati, J.; Brazier, C.É.; Kekki, M.; Parmentier, M.; Neale, B. Qualitative longitudinal research in vocational psychology: A methodological approach to enhance the study of contemporary careers. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlollbey, N.; Vijay, A.; Carr, M.M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on retirement among Canadian otolaryngologists. J. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2025, 54, 19160216251321458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, H.; Vera-Toscano, E. Teacher retention and attrition: Understanding why teachers leave and their post-teaching pathways in Australia. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzachrista, M.; Gkintoni, E.; Halkiopoulos, C. Neurocognitive Profile of Creativity in Improving Academic Performance—A Scoping Review. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E. Clinical neuropsychological characteristics of bipolar disorder, with a focus on cognitive and linguistic pattern: A conceptual analysis. F1000Research 2023, 12, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkintoni, E.; Dimakos, I.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Antonopoulou, H. Contributions of Neuroscience to Educational Praxis: A Systematic Review. Emerg. Sci. J. 2023, 7, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, C.; Rothert-Schnell, C.; Walsh, G.; Mangiò, F.; Pedeliento, G.; Takahashi, I. The digital stress scale: Cross-cultural application, validation, and development of a short scale. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2025, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarska, A.M.; Kryczka, A.; Castellone, D. Organizational trust as a driver of eudaimonic and digital well-being in IT professionals: A cross-cultural study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, F.; Druică, E.; Musso, F.; Krejčová, K.; Sheveleva, M.S.; Herzberg, P.Y.; Karl, J.A. Cross-cultural validation and standardization of the Impostor-Profile 30. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 9987–10000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Meng, Z.X.; Lin, Y.B.; Zhang, L. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the sickness presenteeism scale-nurse (C-SPS-N): A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, G.X.; Mikolajczak, M.; Keller, H.; Akgun, E.; Arikan, G.; Aunola, K.; Roskam, I. Parenting culture(s): Ideal-parent beliefs across 37 countries. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2023, 54, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crede, M.; Fezzey, T.N.; Harms, P.D. A commentary on Palmer et al. (2025): Examinations of cross-cultural generalizability require data reflecting cross-cultural variability. Group Organ. Manag. 2025, 50, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Ortiz, P.S. Neuropsychology of Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Clinical Setting: A Systematic Evaluation. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Barlou, O.; Beligiannis, G.N. Transformational Leadership and Digital Skills in Higher Education Institutes: During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerg. Sci. J. 2021, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Barlou, O.; Beligiannis, G.N. Associations between Traditional and Digital Leadership in Academic Environment: During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerg. Sci. J. 2021, 5, 405–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Barlou, O.; Beligiannis, G.N. Leadership Types and Digital Leadership in Higher Education: Behavioural Data Analysis from University of Patras in Greece. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2020, 19, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, D.D.; Tabler, J.; Okumura, M.J.; Nagata, J.M. Investigating protective factors associated with mental health outcomes in sexual minority youth. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 70, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versteeg, M.; Kappe, R. Resilience and higher education support as protective factors for student academic stress and depression during COVID-19 in the Netherlands. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 737223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, J.; Karrasch, M.; Laine, M.; Fagerlund, Å. Protective factors against school burnout symptoms in Finnish adolescents. Nord. Psychol. 2025, 77, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janousch, C.; Anyan, F.; Morote, R.; Hjemdal, O. Resilience patterns of Swiss adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent transition analysis. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2022, 27, 294–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnert, E.S.; Perry, R.; Shetgiri, R.; Steers, N.; Dudovitz, R.; Heard-Garris, N.J.; Chung, P.J. Adolescent protective and risk factors for incarceration through early adulthood. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 1428–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collett, G.; Korszun, A.; Gupta, A.K. Potential strategies for supporting mental health and mitigating the risk of burnout among healthcare professionals: Insights from the COVID-19 pandemic. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 71, 102562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilton, A.R.; Sheffield, K.; Wilkes, Q.; Chesak, S.; Pacyna, J.; Sharp, R.; Athreya, A.P. The Burnout PRedictiOn Using Wearable aNd ArtIficial IntelligEnce (BROWNIE) study: A decentralized digital health protocol to predict burnout in registered nurses. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forycka, J.; Pawłowicz-Szlarska, E.; Burczyńska, A.; Cegielska, N.; Harendarz, K.; Nowicki, M. Polish medical students facing the pandemic—Assessment of resilience, well-being and burnout in the COVID-19 era. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Via, K.D.; Oliver, J.S.; Shannon, D. Implementing a protocol to address risk for burnout among mental health professionals. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2022, 28, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, C.G.; Sabina, S.; Tumolo, M.R.; Bodini, A.; Ponzini, G.; Sabato, E.; Mincarone, P. Burnout among healthcare workers in the COVID-19 era: A review of the existing literature. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 750529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Søvold, L.E.; Naslund, J.A.; Kousoulis, A.A.; Saxena, S.; Qoronfleh, M.W.; Grobler, C.; Münter, L. Prioritizing the mental health and well-being of healthcare workers: An urgent global public health priority. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 679397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Gui, L. Compassion fatigue, burnout and compassion satisfaction among emergency nurses: A path analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 1294–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drüge, M.; Schladitz, S.; Wirtz, M.A.; Schleider, K. Psychosocial burden and strains of pedagogues—Using the job demands-resources theory to predict burnout, job satisfaction, general state of health, and life satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Vantaraki, F.; Skoulidi, C.; Anastassopoulos, P.; Vantarakis, A. Gamified Health Promotion in Schools: The Integration of Neuropsychological Aspects and CBT—A Systematic Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drăghici, G.L.; Cazan, A.M. Burnout and maladjustment among employed students. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 825588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonopoulou, H.; Matzavinou, P.; Giannoukou, I.; Halkiopoulos, C. Teachers’ Digital Leadership and Competencies in Primary Education: A Cross-Sectional Behavioral Study. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Gkintoni, E.; Katsimpelis, A. Application of Gamification Tools for Identification of Neurocognitive and Social Function in Distance Learning Education. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2022, 21, 367–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulou, H.; Halkiopoulos, C.; Barlou, O.; Beligiannis, G.N. Transition from Educational Leadership to e-Leadership: A Data Analysis Report from TEI of Western Greece. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2019, 18, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Xanthopoulou, D.; Demerouti, E. How does chronic burnout affect dealing with weekly job demands? A test of central propositions in JD-R and COR-theories. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 72, 389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sortwell, A.; Evgenia, G.; Zagarella, S.; Granacher, U.; Forte, P.; Ferraz, R.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Carter-Thuillier, B.; Konukman, F.; Nouri, A.; et al. Making neuroscience a priority in Initial Teacher Education curricula: A call for bridging the gap between research and future practices in the classroom. Neurosci. Res. Notes 2023, 6, 266.1–266.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkintoni, E.; Dimakos, I.; Nikolaou, G. Cognitive Insights from Emotional Intelligence: A Systematic Review of EI Models in Educational Achievement. Emerg. Sci. J. 2025, 8, 262–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Kim, L.E.; Glandorf, H.L. Interventions to reduce burnout in students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 39, 931–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 30 | 26.3 |

| Female | 84 | 73.7 | |

| Age Group | <25 | 6 | 5.3 |

| 25–30 | 12 | 10.5 | |

| 31–35 | 32 | 28.1 | |

| 36–40 | 17 | 14.9 | |

| 41–45 | 14 | 12.3 | |

| 46–50 | 18 | 15.8 | |

| 51+ | 15 | 13.2 | |

| Education Level | Postgraduate | 56 | 49.1 |

| University | 43 | 37.7 | |

| Pedagogical Academy | 8 | 7.0 | |

| Additional Degree | 3 | 2.6 | |

| Other | 4 | 3.5 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 69 | 60.5 |

| Unmarried | 40 | 35.1 | |

| Divorced | 4 | 3.5 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.9 | |

| Prefecture | Achaia | 70 | 61.4 |

| Aitoloakarnania | 44 | 38.6 | |

| Employment Status | Permanent | 60 | 52.6 |

| Substitute | 54 | 47.4 | |

| School Type | Special School | 51 | 44.7 |

| General School—Integration | 33 | 28.9 | |

| General School—Parallel Support | 30 | 26.3 |

| Burnout Dimension | Level | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Exhaustion | Low (≤20) | 52 | 45.6 |

| Medium (21–40) | 51 | 44.7 | |

| High (≥41) | 11 | 9.6 | |

| Personal Achievement * | Low (≤12) | 77 | 67.5 |

| Medium (13–24) | 36 | 31.6 | |

| High (≥25) | 1 | 0.9 | |

| Depersonalization | Low (≤10) | 84 | 73.7 |

| Medium (11–20) | 24 | 21.1 | |

| High (≥21) | 6 | 5.3 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | — | ||||||||

| 2. Years of Experience | 0.847 ** | — | |||||||

| 3. Gender | −0.156 | −0.134 | — | ||||||

| 4. Education Level | 0.234 * | 0.201 * | −0.089 | — | |||||

| 5. Emotional Exhaustion | −0.198 * | −0.187 * | 0.156 | −0.123 | — | ||||

| 6. Personal Achievement | 0.089 | 0.076 | −0.201 * | 0.134 | −0.234 * | — | |||

| 7. Depersonalization | −0.234 * | −0.198 * | 0.287 ** | −0.156 | 0.456 ** | −0.189 * | — | ||

| 8. COVID-19 Impact | −0.145 | −0.134 | 0.123 | −0.089 | 0.547 ** | 0.013 | 0.150 | — | |

| 9. Employment Status | 0.345 ** | 0.298 ** | −0.234 * | 0.178 | −0.189 * | 0.123 | −0.267 ** | −0.156 | — |

| Burnout Dimension | Male (n = 30) | Female (n = 84) | t | df | p | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||||

| Emotional Exhaustion | 25.47 (18.23) | 22.65 (16.12) | 0.82 | 112 | 0.415 | 0.17 |

| Personal Achievement | 11.20 (9.45) | 10.04 (8.34) | 0.67 | 112 | 0.506 | 0.13 |

| Depersonalization | 9.73 (9.12) | 5.89 (7.23) | 2.34 | 112 | 0.021 * | 0.47 |

| Burnout Dimension | F | df | p | η2 | Post Hoc Comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Exhaustion | 3.47 | (6, 107) | 0.003 ** | 0.163 | 31–35 > 46–50, 51+ |

| Personal Achievement | 1.23 | (6, 107) | 0.295 | 0.065 | — |

| Depersonalization | 2.89 | (6, 107) | 0.012 * | 0.139 | <25, 25–30 > 46–50, 51+ |

| Variable | Comparison | t/F | df | p | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Status | |||||

| Emotional Exhaustion | Permanent vs. Substitute | −1.45 | 112 | 0.150 | d = 0.27 |

| Personal Achievement | Permanent vs. Substitute | 0.89 | 112 | 0.376 | d = 0.17 |

| Depersonalization | Permanent vs. Substitute | −2.67 | 112 | 0.009 ** | d = 0.51 |

| School Type | |||||

| Emotional Exhaustion | Between groups | 4.23 | (2, 111) | 0.017 * | η2 = 0.071 |

| Personal Achievement | Between groups | 1.56 | (2, 111) | 0.214 | η2 = 0.027 |

| Depersonalization | Between groups | 2.89 | (2, 111) | 0.059 | η2 = 0.049 |

| Variable | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| β | β | β | |

| Step 1: Demographics | |||

| Age | −0.089 | 0.067 | 0.078 |

| Gender | 0.134 | 0.023 | 0.034 |

| Education Level | −0.076 | −0.045 | −0.039 |

| Employment Status | −0.123 | −0.089 | −0.076 |

| Step 2: Burnout Dimensions | |||

| Emotional Exhaustion | 0.512 ** | 0.498 ** | |

| Personal Achievement | −0.067 | −0.089 | |

| Depersonalization | −0.078 | −0.045 | |

| Step 3: Interactions | |||

| Gender × Emotional Exhaustion | 0.156 | ||

| Employment × Emotional Exhaustion | −0.134 | ||

| R2 | 0.045 | 0.334 | 0.367 |

| ΔR2 | 0.045 | 0.289 ** | 0.033 |

| F | 1.28 | 8.93 ** | 7.45 ** |

| Burnout Dimension | r | p |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional Exhaustion | 0.547 ** | <0.001 |

| Personal Achievement | 0.013 | 0.890 |

| Depersonalization | 0.150 | 0.111 |

| Predictor Variable | β | p | R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Exhaustion | 0.366 ** | <0.001 | 0.299 | 47.60 ** |

| Personal Achievement | 0.007 | 0.890 | 0.000 | 0.02 |

| Depersonalization | 0.113 | 0.111 | 0.023 | 2.58 |

| Cluster | n | % | Emotional Exhaustion M (SD) | Personal Achievement M (SD) | Depersonalization M (SD) | Profile Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | 42 | 36.8 | 12.33 (8.12) | 6.21 (4.45) | 3.14 (3.22) | Low-Burnout Profile: Resilient teachers with minimal symptoms across all dimensions |

| Cluster 2 | 35 | 30.7 | 28.91 (12.45) | 8.77 (6.33) | 5.89 (4.11) | Moderate Emotional Exhaustion: Emotionally strained but maintaining professional efficacy |

| Cluster 3 | 25 | 21.9 | 35.44 (14.22) | 15.88 (8.91) | 12.36 (7.55) | High-Risk Profile: Elevated symptoms requiring immediate intervention |

| Cluster 4 | 12 | 10.5 | 22.17 (10.33) | 18.25 (7.44) | 15.42 (6.88) | Depersonalization-Dominant: Interpersonal detachment with compromised achievement |

| Predictor Variable | Importance Score | Primary Split Criteria | Classification Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Status | 0.89 | Substitute vs. Permanent | 78.9% |

| Years of Experience | 0.76 | ≤5 years vs. >5 years | 73.2% |

| Age Group | 0.68 | ≤35 years vs. >35 years | 69.3% |

| Gender | 0.54 | Male vs. Female | 64.1% |

| School Type | 0.41 | Special vs. General School | 58.7% |

| Education Level | 0.33 | University vs. Postgraduate | 55.4% |

| Rule | Support | Confidence | Lift | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| {Male, Substitute} → {High Depersonalization} | 0.18 | 0.85 | 2.31 | Male substitute teachers strongly associated with high depersonalization |

| {Age ≤ 30, Experience ≤ 3} → {High Emotional Exhaustion} | 0.16 | 0.78 | 2.14 | Young, inexperienced teachers were prone to emotional exhaustion |

| {Special School, Substitute} → {Moderate–High Burnout} | 0.21 | 0.73 | 1.89 | Substitute teachers in special schools at increased burnout risk |

| {Female, Permanent, Experience > 10} → {Low Burnout} | 0.24 | 0.81 | 1.76 | Experienced female permanent teachers show resilience |

| {Postgraduate, Age > 40} → {High Personal Achievement} | 0.19 | 0.75 | 1.68 | Older, highly educated teachers maintain strong sense of accomplishment |

| Algorithm | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | AUC-ROC | Cross-Validation RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.847 | 0.823 | 0.841 | 0.832 | 0.891 | 1.23 |

| Support Vector Machine | 0.812 | 0.798 | 0.805 | 0.801 | 0.856 | 1.45 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.834 | 0.819 | 0.827 | 0.823 | 0.878 | 1.31 |

| Logistic Regression | 0.789 | 0.775 | 0.781 | 0.778 | 0.823 | 1.58 |

| Neural Network | 0.823 | 0.809 | 0.816 | 0.812 | 0.867 | 1.38 |

| Anomaly Type | n | % | Characteristics | Intervention Priority |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme High Burnout | 8 | 7.0 | All dimensions > 90th percentile | Critical |

| Paradoxical Pattern | 6 | 5.3 | High achievement with high exhaustion | High |

| Isolated Depersonalization | 4 | 3.5 | High depersonalization only | Moderate |

| Resilient Outliers | 9 | 7.9 | Extremely low burnout despite risk factors | Study for protective factors |

| Node (Variable) | Degree Centrality | Betweenness Centrality | Closeness Centrality | Hub Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Exhaustion | 0.89 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.92 |

| Employment Status | 0.72 | 0.54 | 0.65 | 0.76 |

| Age Group | 0.68 | 0.48 | 0.61 | 0.71 |

| Depersonalization | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.58 | 0.64 |

| COVID-19 Impact | 0.58 | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.61 |

| Personal Achievement | 0.45 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.47 |

| Gender | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.43 |

| School Type | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.39 | 0.35 |

| Career Stage | n | Years Range | Emotional Exhaustion M (SD) | Personal Achievement M (SD) | Depersonalization M (SD) | Risk Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novice | 28 | 0–2 years | 28.14 (15.67) | 12.45 (7.89) | 8.21 (6.33) | High Risk |

| Developing | 31 | 3–7 years | 25.87 (14.23) | 10.77 (6.44) | 7.12 (5.67) | Moderate Risk |

| Established | 35 | 8–15 years | 20.91 (12.45) | 8.88 (5.22) | 5.44 (4.11) | Low-Moderate Risk |

| Veteran | 20 | 16+ years | 18.33 (11.78) | 7.65 (4.99) | 4.89 (3.88) | Low Risk |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alexaki, P.-S.; Antonopoulou, H.; Gkintoni, E.; Adamopoulos, N.; Halkiopoulos, C. Psychological Dimensions of Professional Burnout in Special Education: A Cross-Sectional Behavioral Data Analysis of Emotional Exhaustion, Personal Achievement, and Depersonalization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091420

Alexaki P-S, Antonopoulou H, Gkintoni E, Adamopoulos N, Halkiopoulos C. Psychological Dimensions of Professional Burnout in Special Education: A Cross-Sectional Behavioral Data Analysis of Emotional Exhaustion, Personal Achievement, and Depersonalization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091420

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlexaki, Paraskevi-Spyridoula, Hera Antonopoulou, Evgenia Gkintoni, Nikos Adamopoulos, and Constantinos Halkiopoulos. 2025. "Psychological Dimensions of Professional Burnout in Special Education: A Cross-Sectional Behavioral Data Analysis of Emotional Exhaustion, Personal Achievement, and Depersonalization" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091420

APA StyleAlexaki, P.-S., Antonopoulou, H., Gkintoni, E., Adamopoulos, N., & Halkiopoulos, C. (2025). Psychological Dimensions of Professional Burnout in Special Education: A Cross-Sectional Behavioral Data Analysis of Emotional Exhaustion, Personal Achievement, and Depersonalization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091420