Exploring Women’s Perceived Quality of Antenatal Care: A Cross-Sectional Study in The Netherlands

Abstract

1. Introduction

- –

- How pregnant women in the Netherlands perceive the quality of antenatal care;

- –

- The association between perceived quality of antenatal care and experience of continuity during antenatal care and the key recommendations in the integrated maternity care standard: implementation of a maternity care plan and a coordinating care professional.

2. Materials and Methods

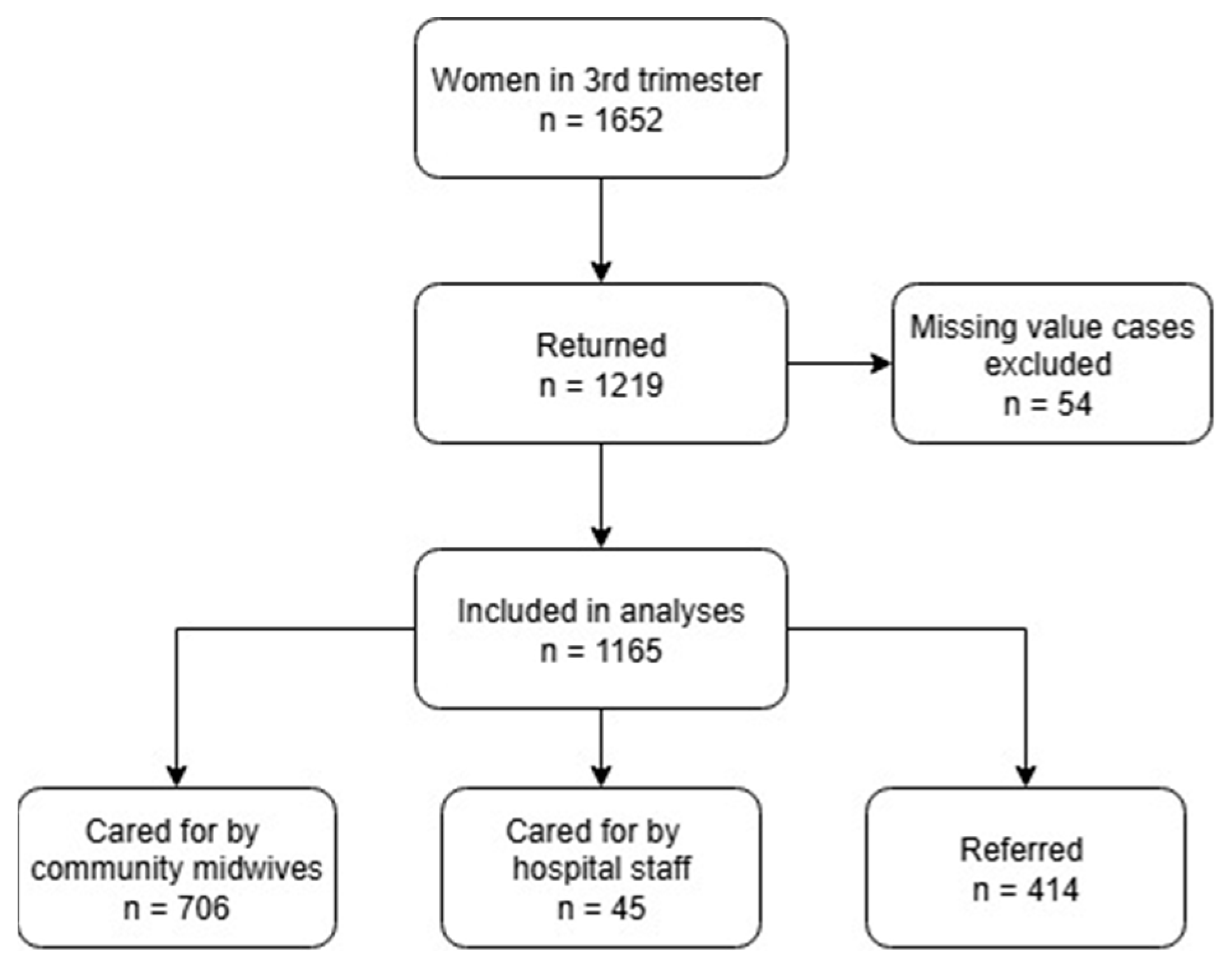

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Results

4.2. Interpretation of Results

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| PCQ1 (Personal Treatment) | PCQ2 (Educational Information) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandard. β | Standard. β | p | CI | Unstandard. β | Standard. β | p | CI | |

| NCQ1community midwives | 0.109 | 0.162 | <0.008 | [0.028–0.190] | 0.207 | 0.247 | <0.001 | [0.108–0.306] |

| NCQ2community midwives | 0.145 | 0.212 | <0.001 | [0.071–0.219] | 0.174 | 0.205 | <0.001 | [0.074–0.274] |

| NCQ3community midwives | 0.192 | 0.270 | <0.001 | [0.114–0.270] | ||||

| Coordinating care professional | 0.119 | 0.120 | 0.004 | [0.039–0.198] | - | - | - | - |

| Referral status | ||||||||

| Unreferred | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Referred | −0.097 | −0.098 | <0.001 | [−0.176–−0.019] | −0.079 | −0.130 | 0.004 | [−0.269–−0.051] |

| R2 = 0.375 | R2 = 0.190 | |||||||

| PCQ1 (Personal Treatment) | PCQ2 (Educational Information) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstandard. β | Standard. β | p | CI | Unstandard. β | Standard. β | p | CI | |

| NCQ3hospital staff | 0.211 | 0.329 | <0.001 | [0.131–0.291] | 0.224 | 0.300 | <0.001 | [0.129–0.318] |

| Coordinating care professional | 0.169 | 0.155 | 0.016 | [0.032–0.305] | 0.166 | 0.131 | 0.043 | [0.556–0.273] |

| Experienced number of care professionals | ||||||||

| Many | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Few | 0.242 | 0.218 | <0.001 | [0.103–0.381] | 0.337 | 0.262 | <0.001 | [0.174–0.499] |

| Referral status | ||||||||

| Unreferred | Reference | |||||||

| Referred | 0.258 | 0.164 | 0.010 | [0.062–0.454] | - | - | ||

| R2 = 0.232 | R2 = 0.198 | |||||||

References

- Downe, S.; Finlayson, K.; Tunçalp Metin Gülmezoglu, A. What matters to women: A systematic scoping review to identify the processes and outcomes of antenatal care provision that are important to healthy pregnant women. BJOG 2016, 123, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfrew, M.J.; McFadden, A.; Bastos, M.H.; Campbell, J.; Channon, A.A.; Cheung, N.F.; Silva, D.R.A.D.; Downe, S.; Kennedy, H.P.; Malata, A.; et al. Midwifery and quality care: Findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet 2014, 384, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattof, S.R.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Moran, A.C.; Bucagu, M.; Chou, D.; Diaz, T.; Gülmezoglu, A.M. Developing measures for WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience: A conceptual framework and scoping review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunçalp, Ӧ.; Pena-Rosas, J.; Lawrie, T.; Bucagu, M.; Oladapo, O.; Portela, A.; Gülmezoglu, A.M. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience—Going beyond survival. BJOG 2017, 124, 860–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, M.G.; Ford, J.B.; Todd, A.L.; Forsyth, R.; Morris, J.M.; Roberts, C.L. Women׳s views about maternity care: How do women conceptualise the process of continuity? Midwifery 2015, 31, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlen, H.G.; Barclay, L.M.; Homer, C. Preparing for the First Birth: Mothers’ Experiences at Home and in Hospital in Australia. J. Perinat. Educ. 2008, 17, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandall, J.; Turienzo, C.F.; Devane, D.; Soltani, H.; Gillespie, P.; Gates, S.; Jones, L.V.; Shennan, A.H.; Rayment-Jones, H. Midwife Continuity of Care Models Versus Other Models of Care for Childbearing Women; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; Volume 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perriman, N.; Davis, D.L.; Ferguson, S. What women value in the midwifery continuity of care model: A systematic review with meta-synthesis. Midwifery 2018, 62, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogels-Broeke, M.; De Vries, R.; Nieuwenhuijze, M. Validating a framework of women’s experiences during the perinatal period; a scoping review. Midwifery 2021, 92, 102866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçalp, Ö.; Were, W.M.; MacLennan, C.; Oladapo, O.T.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Bahl, R.; Daelmans, B.; Mathai, M.; Say, L.; Kristensen, F.; et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns—The WHO vision. BJOG 2015, 122, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattof, S.R.; Moran, A.C.; Kidula, N.; Moller, A.-B.; Jayathilaka, C.A.; Diaz, T.; Tunçalp, Ö. Implementation of the new WHO antenatal care model for a positive pregnancy experience: A monitoring framework. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrtash, H.; Stein, K.; Barreix, M.; Bonet, M.; Bohren, M.A.; Tunçalp, Ö. Measuring women’s experiences during antenatal care (ANC): Scoping review of measurement tools. Reprod. Health 2023, 20, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, K.; Reid, C.N.; Cabral, N.; Marshall, J.; Menon, U. Exploring Patients’ Needs and Desires for Quality Prenatal Care in Florida, United States. Int. J. Matern. Child Health AIDS 2023, 12, e622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truijens, S.E.M.; Pommer, A.M.; Van Runnard Heimel, P.J.; Verhoeven, C.J.M.; Oei, S.G.; Pop, V.J.M. Development of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Questionnaire (PCQ): Evaluating quality of care as perceived by women who recently gave birth. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2014, 174, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, B.F.; Wilson, A.N.; Portela, A.; McConville, F.; Fernandez Turienzo, C.; Homer, C.S.E. Midwifery continuity of care: A scoping review of where, how, by whom and for whom? PLOS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdok, H.; Verhoeven, C.J.; van Dillen, J.; Schuitmaker, T.J.; Hoogendoorn, K.; Colli, J.; Schellevis, F.G.; de Jonge, A. Continuity of care is an important and distinct aspect of childbirth experience: Findings of a survey evaluating experienced continuity of care, experienced quality of care and women’s perception of labor. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroll-Desrosiers, A.R.; Crawford, S.L.; Moore Simas, T.A.; Rosen, A.K.; Mattocks, K.M. Improving Pregnancy Outcomes through Maternity Care Coordination: A Systematic Review. Women’s Health Issues 2016, 26, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.; Des Rivières-Pigeon, C. A literature review on integrated perinatal care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2007, 7, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggerty, J.L.; Reid, R.J.; Freeman, G.K.; Starfield, B.H.; Adair, C.E.; Mckendry, R. Continuity of care: A multidisciplinary review. BMJ 2003, 327, 1219–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggerty, J.L.; Reid, R.J.; Freeman, G.K.; Starfield, B.H.; Adair, C.E.; McKendry, R. Continuity of Care 2006: What Have We Learned Since 2000 and What are Policy Imperatives Now? Report for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO); National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO): London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Uijen, A.; Schellevis, F.; Van den Bosch, W.; Mokkink, H.; Van Weel, C.; Schers, H. Nijmegen Continuity Questionnaire: Development and testing of a questionnaire that measures continuity of care. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.; Scarf, V.; Turkmani, S.; Rossiter, C.; Coddington, R.; Sheehy, A.; Catling, C.; Cummins, A.; Baird, K. Midwifery continuity of care for women with complex pregnancies in Australia: An integrative review. Women Birth 2022, 36, e187–e194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homer, C.S.E. Models of maternity care: Evidence for midwifery continuity of care. Med. J. Aust. 2016, 205, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontein, J. The comparison of birth outcomes and birth experiences of low-risk women in different sized midwifery practices in the Netherlands. Women Birth 2010, 23, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez Turienzo, C.; Rayment-Jones, H.; Roe, Y.; Silverio, S.A.; Coxon, K.; Shennan, A.H.; Sandall, J. A realist review to explore how midwifery continuity of care may influence preterm birth in pregnant women. Birth 2021, 48, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, E.; Sharma, J.; Nasiri, K.; Bohren, M.A.; Tunçalp, Ö. Measuring experiences of facility-based care for pregnant women and newborns: A scoping review. BMJ Global Health 2020, 5, e003368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, R.; Nieuwenhuijze, M.; Buitendijk, S.E. What does it take to have a strong and independent profession of midwifery? Lessons from the Netherlands. Midwifery 2013, 29, 1122–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelink-Verburg, M.P.; Buitendijk, S.E. Pregnancy and labour in the dutch maternity care system: What is normal? The role division between midwives and obstetricians. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2010, 55, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmelink, R.; Neppelenbroek, E.; Pouwels, A.; van der Lee, N.; Pajkrt, E.; Ziesemer, K.A.; van der Vliet-Torij, H.W.H.; Verhoeven, C.J.M.; de Jonge, A.; Nieuwenhuijze, M. Understanding how midwife-led continuity of care can be implemented and under what circumstances: A realist review. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e091968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- College Perinatale Zorg. Zorgstandaard Integrale Geboortezorg 1.0. [Integrated Maternity Care Standard]; College Perinatale Zorg: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- College Perinatale Zorg. Zorgstandaard Integrale Geboortezorg 1.2 [Integrated Maternity Care Standard]; College Perinatale Zorg: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stuurgroep. Een Goed Begin: Veilige Zorg Rond Zwangerschap en Geboorte. [A Good Start: Safe Maternity Care]; Stuurgroep: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens, S.M.P.; Van Montfort, P.; Meertens, L.J.E.; Spaanderman, M.E.A.; Smits, L.J.M.; De Vries, R.G.; Scheepers, H.C.J. Perinatal factors related to pregnancy and childbirth satisfaction: A prospective cohort study. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 42, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogels-Broeke, M.A. Stem [Stem en Ervaringen van Moeders]. Ph.D. Thesis, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perined. General Maternity Care Population in The Netherlands in 2019; Perined: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; Available online: https://www.peristat.nl (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Uijen, A.; Schers, H.J.; Schellevis, F.; Mokkink, H.; Van Weel, C.; Van den Bosch, W. Measuring continuity of care: Psychometric properties of the Nijmegen Continuity Questionnaire. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2012, 62, e949–e957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baart, A.; Brunsveld Reinders, A.H.; Pijnappel, L.; de Haan, M.; de Man van Ginkel, J. Continuity of care as central theme in perinatal care: A systematic review. Midwifery 2025, 141, 104273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posthumus, A.G.; Schölmerich, V.L.N.; Waelput, A.J.M.; Vos, A.A.; De Jong-Potjer, L.C.; Bakker, R.; Bonsel, G.J.; Groenewegen, P.; Steegers, E.A.P.; Denktaş, S. Bridging between professionals in perinatal care: Towards shared care in the Netherlands. Matern. Child Health J. 2013, 17, 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khatri, R.B.; Mengistu, T.S.; Assefa, Y. Input, process, and output factors contributing to quality of antenatal care services: A scoping review of evidence. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afulani, P.A.; Sayi, T.S.; Montagu, D. Predictors of person-centered maternity care: The role of socioeconomic status, empowerment, and facility type. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, J.; Gao, H.; Redshaw, M. Experiencing maternity care: The care received and perceptions of women from different ethnic groups. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truijens, S.E.M.; Banga, F.R.; Fransen, A.F.; Pop, V.J.M.; Van Runnard Heimel, P.J.; Oei, S.G. The effect of multiprofessional simulation-based obstetric team training on patient-reported quality of care: A pilot study. Simul. Healthc. 2015, 10, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wolff, M.G.; Midtgaard, J.; Johansen, M.; Rom, A.L.; Rosthøj, S.; Tabor, A.; Hegaard, H.K. Effects of a midwife-coordinated maternity care intervention (Chropreg) vs. standard care in pregnant women with chronic medical conditions: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedeler, C.; Nilsen, A.B.V.; Blix, E.; Downe, S.; Eri, T.S. What women emphasise as important aspects of care in childbirth—An online survey. BJOG 2022, 129, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, K.M.; Sundaram, V.; Bravata, D.M.; Lewis, R.; Lin, N.; Kraft, S.A.; McKinnon, M.; Paguntalan, H.; Owens, D.K. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 7: Care Coordination); Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, M.C.H.; Muggleton, S.; Davis, D.L. Birth plans: A systematic, integrative review into their purpose, process, and impact. Midwifery 2022, 111, 103388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenen, C.J.M.; van Duijnhoven, N.T.L.; Faber, M.J.; Koetsenruijter, J.; Kremer, J.A.M.; Vandenbussche, F.P.H.A. Use of social network analysis in maternity care to identify the profession most suited for case manager role. Midwifery 2017, 45, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, N.; Scholten, N.; Nieuwenhuijze, M.; Stramrood, C.; de Vries, M.; van Dillen, J. The role of birth plans for shared decision-making around birth choices of pregnant women in maternity care: A scoping review. Women Birth 2022, 36, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemeskel, S.; Alemu, K.; Christensson, K.; Tesfahun, E.; Lindgren, H. Midwife-led continuity of care increases women’s satisfaction with antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care: North Shoa, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia: A quasi-experimental study. Women Birth 2022, 35, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Total (n = 1.165) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | |

| Age in years | Mean 30.5 | |

| Educational level | ||

| Low | 56 | (4.8) |

| Middle | 427 | (36.7) |

| High | 682 | (58.5) |

| Parity | ||

| Nulliparous | 439 | (37.7) |

| Multiparous | 726 | (62.3) |

| Nationality | ||

| Dutch | 1035 | (89.8) |

| Non-Dutch | 130 | (11.2) |

| Experienced a maternity care plan | ||

| Yes | 264 | (22.7) |

| No | 901 | (77.3) |

| Experienced a coordinating care professional | ||

| Yes | 502 | (43.1) |

| No | 663 | (56.9) |

| Experienced number of care professionals | ||

| Many | 426 | (36.6) |

| Few | 739 | (63.4) |

| Referral status | ||

| Unreferred | ||

| Community midwives | 706 | (60.6) |

| Hospital staff | 45 | (3.9) |

| Referred | 414 | (35.5) |

| Total (n = 1.165) | Community Midwives (n = 706) | Hospital Staff (n = 45) | Women Who Were Referred (n = 414) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (sd) | Mean | (sd) | Mean | (sd) | Mean | (sd) | |||

| PCQ 1 Personal treatment | 4.30 | (0.47) | 4.34 | (0.44) | 3.98 | (0.54) | p < 0.001 * | 4.25 | (0.49) | p < 0.001 * |

| PCQ 2 Educational information during pregnancy | 3.87 | (0.62) | 3.90 | (0.62) | 3.70 | (0.64 | p < 0.016 * | 3.84 | (0.62) | p < 0.045 * |

| A | ||||||||

| PCQ1 (Personal Treatment) | PCQ2 (Educational Information) | |||||||

| Unstandard. β | Standard. β | p | CI | Unstandard. β | Standard. β | p | CI | |

| NCQ1community midwives | 0.169 | 0.270 | <0.001 | [0.127–0.211] | 0.205 | 0.245 | <0.001 | [0.146–0.263] |

| NCQ2community midwives | 0.133 | 0.202 | <0.001 | [0.091–0.175] | 0.221 | 0.251 | <0.001 | [0.159–0.283] |

| NCQ3community midwives | 0.112 | 0.178 | <0.001 | [0.077–0.143] | ||||

| Parity | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Nulliparous | Reference | |||||||

| Multiparous | −0.049 | −0.051 | 0.034 | [−0.093–−0.004] | ||||

| Coordinating care professional | 0.120 | 0.129 | <0.001 | [0.074–0.166] | - | - | - | - |

| Experienced number of care professionals | ||||||||

| Many | Reference | - | - | |||||

| Few | 0.087 | 0.091 | <0.001 | [0.039–0.136] | - | - | ||

| Referral status | ||||||||

| Unreferred | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Referred | −0.084 | −0.088 | <0.001 | [−0.131–−0.038] | −0.079 | −0.061 | 0.024 | [−0.147–−0.011] |

| R2 = 0.375 | R2 = 0.206 | |||||||

| B | ||||||||

| PCQ1 (Personal Treatment) | PCQ2 (Educational Information) | |||||||

| Unstandard. β | Standard. β | p | CI | Unstandard. β | Standard. β | p | CI | |

| NCQ3 hospital staff | 0.175 | 0.250 | <0.001 | [0.117–0.232] | 0.168 | 0.193 | <0.001 | [0.093–0.243] |

| Coordinating care professional | 0.181 | 0.181 | <0.001 | [0.097–0.264] | 0.165 | 0.132 | 0.003 | [0.556–0.273] |

| Experienced number of care professionals | ||||||||

| Many | Reference | Reference | ||||||

| Few | 0.249 | 0.249 | <0.001 | [0.165–0.332] | 0.299 | 0.241 | <0.001 | [0.191–0.408] |

| Referral status | ||||||||

| Unreferred | Reference | |||||||

| Referred | 0.267 | 0.159 | <0.001 | [0.129–0.406] | - | - | ||

| R2 = 0.205 | R2 = 0.126 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cellissen, E.; Hendrix, M.; Vogels-Broeke, M.; Budé, L.; Nieuwenhuijze, M. Exploring Women’s Perceived Quality of Antenatal Care: A Cross-Sectional Study in The Netherlands. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091392

Cellissen E, Hendrix M, Vogels-Broeke M, Budé L, Nieuwenhuijze M. Exploring Women’s Perceived Quality of Antenatal Care: A Cross-Sectional Study in The Netherlands. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091392

Chicago/Turabian StyleCellissen, Evelien, Marijke Hendrix, Maaike Vogels-Broeke, Luc Budé, and Marianne Nieuwenhuijze. 2025. "Exploring Women’s Perceived Quality of Antenatal Care: A Cross-Sectional Study in The Netherlands" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091392

APA StyleCellissen, E., Hendrix, M., Vogels-Broeke, M., Budé, L., & Nieuwenhuijze, M. (2025). Exploring Women’s Perceived Quality of Antenatal Care: A Cross-Sectional Study in The Netherlands. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091392