Burnout Syndrome Among Dental Students in Clinical Training: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study in Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Collection

2.2. Participants and Sample Calculation

2.3. Research Instruments

- -

- Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI): A 22-item questionnaire that assesses three core dimensions of burnout syndrome: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. Each item is rated on a Likert-type frequency scale. The total score allows classification of participants into three categories: no risk (0–43 points), at risk (44–87 points), and presence of burnout syndrome (>88 points) [21,22]. This questionnaire was validated by Carlotto in Brazil [23].

- -

- Burnout-Associated Symptom Questionnaire: A complementary instrument consisting of 14 items designed to assess the frequency of physical and emotional symptoms such as chronic fatigue, insomnia, headaches, neck pain, digestive discomfort, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain. A 7-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 6), where 0 indicates “never” and 6 indicates “always,” was used to estimate the students’ symptom burden [21,24,25].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Contributions

4.1.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.1.2. Practical Contributions

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Areas for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atroszko, P.A.; Demetrovics, Z.; Griffiths, M.D. Work Addiction, Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder, Burn-Out, and Global Burden of Disease: Implications from the ICD-11. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhardt, P.; Ellbin, S.; Carlander, A.; Hadzibajramovic, E.; Jonsdottir, I.H.; Lindqvist Bagge, A. Is the road to burnout paved with perfectionism? The prevalence of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder in a clinical longitudinal sample of female patients with stress-related exhaustion. J. Clin. Psychol. 2024, 80, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, S.A.A.M.; Elotla, S.F.; Ameen, A.E.; Shah, J.; Fouad, A.M. Occupational Burnout and Productivity Loss: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Academic University Staff. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 861674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freudenberger, H.J. Staff Burn-Out. J. Soc. Issues 1974, 30, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuradha, R.; Dutta, R.; Raja, J.D.; Sivaprakasam, P.; Patil, A.B. Stress and Stressors among Medical Undergraduate Students: A Cross-sectional Study in a Private Medical College in Tamil Nadu. Indian. J. Community Med. 2017, 42, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Almagro, F.; Carmona-Monge, F.J.; García-Hedrera, F.J.; Peñacoba-Puente, C. Evolution of burnout syndrome in Spanish healthcare professionals during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: Psychosocial variables involved. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1522134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo-Vázquez Cm Martín, C.; Sáez-Alcaide Lm Meniz-García, C.; Baca, L.; Molinero-Mourelle, P.; López-Quiles, J. Burnout syndrome assessment among Spanish oral surgery consultants: A two populations comparative pilot study. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cirugia Bucal 2022, 27, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, D.B.; Ellis, R.J.; Hu, Y.Y.; Cheung, E.O.; Moskowitz, J.T.; Agarwal, G.; Bilimoria, K.Y. Evaluating the Association of Multiple Burnout Definitions and Thresholds With Prevalence and Outcomes. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Torre, M.; Ramos, M.A.; Rosales, R.C.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of Burnout Among Physicians: A Systematic Review. JAMA 2018, 320, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsdottir, I.H.; Sjörs Dahlman, A. MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY: Endocrine and immunological aspects of burnout: A narrative review. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 180, R147–R158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciprián Chavelas, T.; Adame Marroquín, E.; Juárez Medel, C.A. Burnout syndrome among dentists of health centers from Acapulco, Mexico. Rev. Cient. Odontol. 2023, 11, e150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.A.D.B.; Jordani, P.C.; Zucoloto, M.L.; Bonafé, F.S.S.; Maroco, J. Burnout syndrome among dental students. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2012, 15, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahem, A.M.; Van der Molen, H.T.; Alaujan, A.H.; De Boer, B.J. Stress management in dental students: A systematic review. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2014, 5, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqai, S.; Thaver, I.H.; Effendi, F.N. Burnout among Medical and Dental Students: Prevalence, Determinants, and Coping Mechanisms. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2024, 34, 1508–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, R.; Jyoti, B.; Pradhan, D.; Kumar, M.; Priyadarshi, P. Evaluating the stress and its association with stressors among the dental undergraduate students of Kanpur city, India: A cross-sectional study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalayin, C.; Balkis, M.; Tezel, H.; Onal, B.; Kayrak, G. The prevalence and consequences of burnout on a group of preclinical dental students. Eur. J. Dent. 2015, 9, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsen, V.C.; Tharp, A.L.T.; Meguid, T. High rates of burnout among maternal health staff at a referral hospital in Malawi: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2011, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mafla, A.C.; Villa-Torres, L.; Polychronopoulou, A.; Polanco, H.; Moreno-Juvinao, V.; Parra-Galvis, D.; Durán, C.; Villalobos, M.J.; Divaris, K. Burnout prevalence and correlates amongst Colombian dental students: The STRESSCODE study. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2015, 19, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K.; Muller Neff, D.; Pitman, S. Burnout in mental health professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and determinants. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 53, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, L.S.; Sousa, R.M.; Guedes, E.S.; Santos, M.A.; Turrini, R.N.; Cruz, D.A.M. Burnout and nursing work environment in public health institutions. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauca Bajaña, L.A.; Campos Lascano, L.; Jaramillo Castellon, L.; Carpio Cevallos, C.; Cevallos-Pozo, G.; Velasquez Ron, B.; e Silva, F.F.V.; Perez-Sayans, M.; Fiorillo, L. The Prevalence of the Burnout Syndrome and Factors Associated in the Students of Dentistry in Integral Clinic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Dent. 2023, 2023, e5576835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Martínez, I.M.; Pinto, A.M.; Salanova, M.; Bakker, A.B. Burnout and Engagement in University Students: A Cross-National Study. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2002, 33, 464–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroco, J.; Tecedeiro, M. Inventário de burnout de maslach para estudantes portugueses. Psicol. Saúde Doenças. 2009, 10, 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Lara López, N.J. Prevalencia del Síndrome de Burnout en Estudiantes Que se Encuentran Cursando la Clínica V en la Facultad de Odontología de la Universidad de las Américas en el Periodo 2020-1. 2020. Available online: http://dspace.udla.edu.ec/handle/33000/11960 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.Q.; Ahmad, Z.; Muhammad, M.; Binrayes, A.; Niazi, I.; Nawabi, S.; Abulhamael, A.M.; Habib, S.R. Burnout level evaluation of undergraduate dental college students at middle eastern university. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugassy, D.; Ben-Izhack, G.; Zissu, S.; Shitrit Lahav, R.; Rosner, O.; Elzami, R.; Shely, A.; Naishlos, S. Anxiety, stress, and depression levels among dental students: Gender, age, and stage of dental education related. Psychol. Health Med. 2025, 30, 1394–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahem, A.M.; van der Molen, H.T.; Alaujan, A.H.; Schmidt, H.G.; Zamakhshary, M.H. Stress amongst dental students: A systematic review. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2011, 15, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye, L.N.; West, C.P.; Satele, D.; Boone, S.; Tan, L.; Sloan, J.; Shanafelt, T.D. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almutairi, H.; Alsubaiei, A.; Abduljawad, S.; Alshatti, A.; Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Husni, M.; Jahrami, H. Prevalence of burnout in medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erschens, R.; Keifenheim, K.E.; Herrmann-Werner, A.; Loda, T.; Schwille-Kiuntke, J.; Bugaj, T.J.; Nikendei, C.; Huhn, D.; Zipfel, S.; Junne, F. Professional burnout among medical students: Systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, M.; Arsenio, E.; Della Rocca, B.; Rosa, A.; Tretola, L.; Toricco, R.; Boiano, A.; Catapano, P.; Cavaliere, S.; Volpicelli, A.; et al. Is There a Burnout Epidemic among Medical Students? Results from a Systematic Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gobari, M.; Shoman, Y.; Blanc, S.; Canu, I.G. Point prevalence of burnout in Switzerland: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2022, 152, w30229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Suresh, D.; Santhi, G.; Sandhu, N.S.; Kuppusamy, A.; Kumar, S. Relationship of Burnout and Extra-Curricular Activities among Dental Students: An Original Research. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2023, 15, S204–S208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, L.Z.; Foo, L.K.; Chua, S.L. Student Burnout: A Review on Factors Contributing to Burnout Across Different Student Populations. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, M.C.P.; Generoso, I.P.; Sizilio, A.; Bivanco-Lima, D. Burnout syndrome, extracurricular activities and social support among Brazilian internship medical students: A cross-sectional analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almalki, S.A.; Almojali, A.I.; Alothman, A.S.; Masuadi, E.M.; Alaqeel, M.K. Burnout and its association with extracurricular activities among medical students in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2017, 8, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fares, J.; Saadeddin, Z.; Al Tabosh, H.; Aridi, H.; El Mouhayyar, C.; Koleilat, M.K.; Chaaya, M.; El Asmar, K. Extracurricular activities associated with stress and burnout in preclinical medical students. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2016, 6, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, A.; Menouni, A.; Korachi, I.B.; Nejjari, C.; Khalis, M.; Jaafari, S.E.; Godderis, L. Burnout and predictive factors among medical students: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlotto, M.S.; Nakamura, A.P.; Câmara, S.G. Síndrome de Burnout em estudantes universitários da área. Psico 2006, 16, 37. Available online: https://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/revistapsico/article/view/1412 (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Smolana, A.; Loster, Z.; Loster, J. Assessment of stress burden among dental students: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of data. Dent. Med. Probl. 2022, 59, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehan, A.; Anjum, R.; Vijay, P.; Singh, P.; Khanam, W. Burnout in dental students: Navigating stress, exhaustion and academic pressure. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Pathol. 2025, 29, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, E.J.; Ji, Y.A.; Baek, S.H.; Baek, Y.S. High levels of burnout and depression in a population of senior dental students in a school of dentistry in Korea. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, K.C.; Shrivastava, D.; Khan, Z.A.; Nagarajappa, A.K.; Mousa, M.A.; Hamza, M.O.; Al-Johani, K.; Alam, M.K. Evaluation of temporomandibular disorders among dental students of Saudi Arabia using Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD): A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezer, B.; Kartal, S.; Sıddıkoğlu, D.; Kargül, B. Association between work-related musculoskeletal symptoms and quality of life among dental students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, R.; Salah, A.; Mayahi, F.; Haidary, S. Prevalence of postural musculoskeletal symptoms among dental students in United Arab Emirates. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021, 22, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.O.d.M.; Peixoto, R.F.; Resende, C.M.B.M.; Alves, A.C.d.M.; Oliveira ÂGRda Barbosa, G.A.S. Psychosocial aspects and temporomandibular disorders in dental students. Quintessence Int. 2017, 48, 241–249. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 20 to 27 | 280 (89.74) |

| 28 to 35 | 29 (9.29) |

| 36 to 42 | 1 (0.32) |

| Over 42 | 2 (0.64) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 101 (32.37) |

| Female | 211 (67.63) |

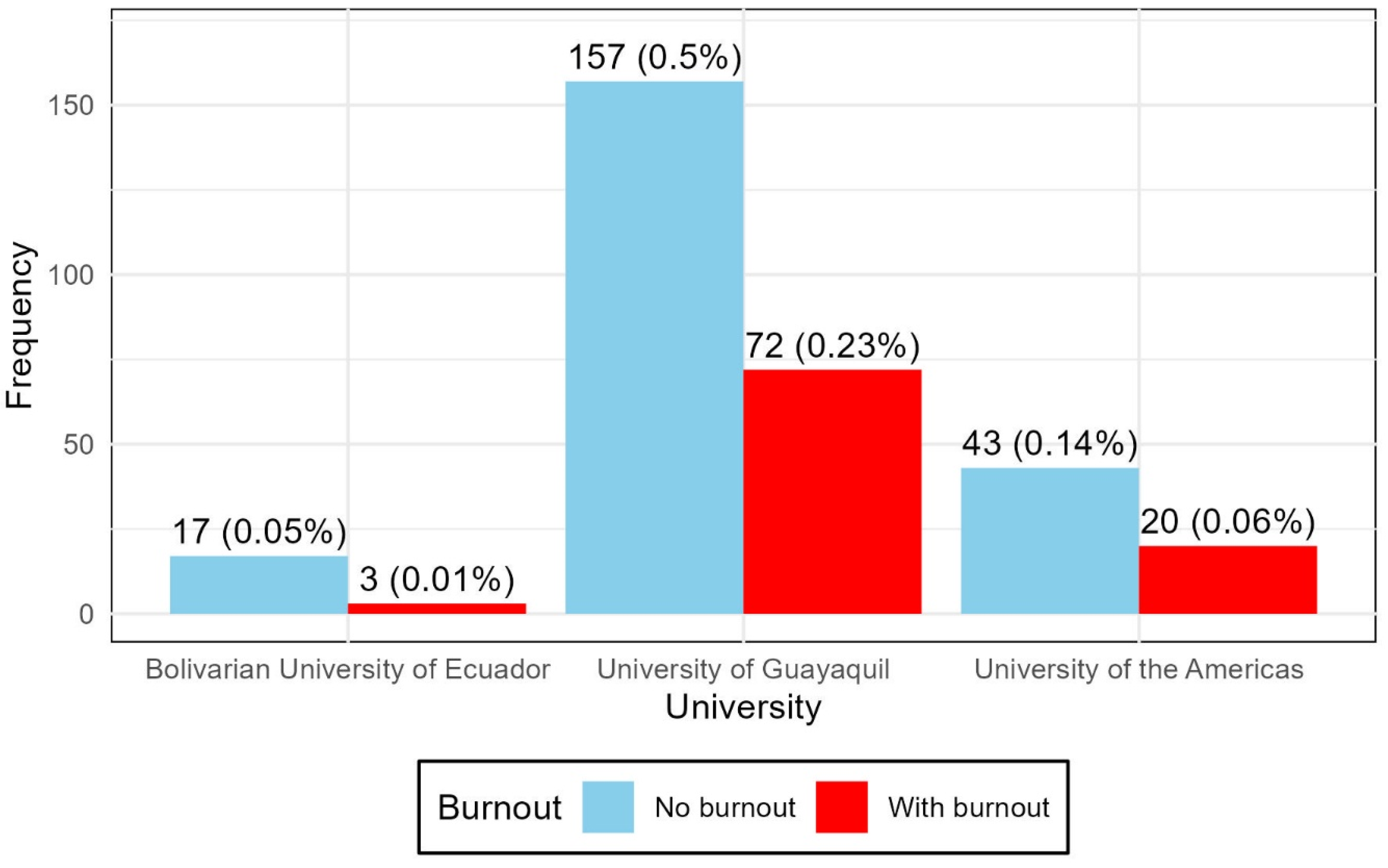

| University | |

| Bolivarian University of Ecuador | 20 (6.41) |

| University of Guayaquil | 229 (73.40) |

| University of the Americas | 63 (20.19) |

| Semester | |

| Eighth | 63 (20.19) |

| Ninth | 157 (50.32) |

| Tenth | 92 (29.49) |

| Level | Emotional Exhaustion n (%) | Depersonalization n (%) | Personal Accomplishment n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | 248 (79.49) | 170 (54.49) | 219 (70.19) |

| Medium | 55 (17.63) | 125 (40.06) | 57 (18.27) |

| Low | 9 (2.88) | 17 (5.45) | 36 (11.54) |

| Estimated Mean (SD) | 28.64 (7.21) | 10 (3.50) | 30.10 (4.60) |

| Presence of Burnout | n (%) |

|---|---|

| No Burnout | 287 (91.99) |

| Burnout Present | 25 (8.01) |

| Total | 312 |

| Relation | Statistical | Gl | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Burnout vs. University | 2.4105 | 2 | 0.2996 |

| Burnout vs. Semester | 0.072 | 2 | 0.9646 |

| Burnout vs. sex | 1.151 | 1 | 0.2834 |

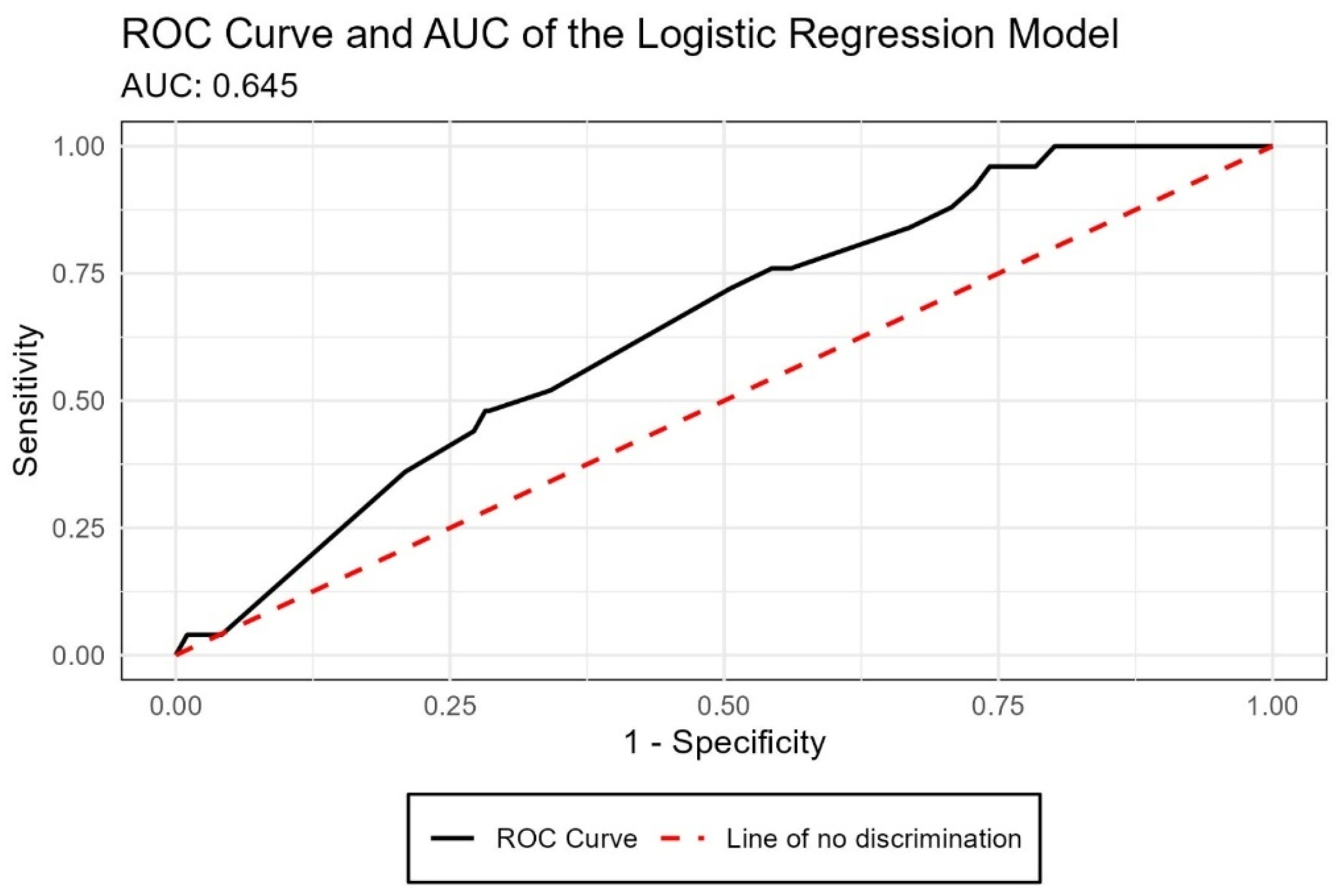

| Variable | β | SE | Z | p-Value | OR | 95% CI (Lower–Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.747 | 0.908 | −3.015 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.01–0.31 |

| Hours of study/work | ||||||

| 11–20 h (vs. ≤10 h) | 0.296 | 0.598 | 0.495 | 0.620 | 1.34 | 0.45–4.99 |

| 21–30 h | 0.251 | 0.761 | 0.330 | 0.742 | 1.29 | 0.28–6.02 |

| More than 30 h | 1.222 | 0.970 | 1.260 | 0.208 | 3.39 | 0.41–21.88 |

| Semester | ||||||

| Ninth (vs. Eighth) | 0.687 | 0.600 | 1.144 | 0.252 | 1.99 | 0.66–7.37 |

| Tenth (vs. Eighth) | 0.270 | 0.661 | 0.409 | 0.683 | 1.31 | 0.37–5.30 |

| University | ||||||

| University of Guayaquil (vs. Bolivarian University of Ecuador) | −0.210 | 0.814 | −0.258 | 0.796 | 0.81 | 0.19–5.55 |

| University of the Americas (vs. Bolivarian University of Ecuador) | −2.374 | 1.30 | −1.832 | 0.067 | 0.09 | 0.00–1.10 |

| Symptoms | Never n (%) | Few Times n (%) | Sometimes n (%) | Frequently n (%) | Always n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enjoy activities | 20 (6.41) | 67 (21.47) | 132 (42.31) | 68 (21.79) | 25 (8.01) |

| Headaches | 7 (2.24) | 34 (10.9) | 93 (29.81) | 83 (26.6) | 95 (30.45) |

| Neck pain | 15 (4.81) | 22 (7.05) | 87 (27.88) | 76 (24.36) | 112 (35.9) |

| Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain | 86 (27.56) | 70 (22.44) | 74 (23.72) | 39 (12.5) | 43 (13.78) |

| Back and waist pain | 7 (2.24) | 17 (5.45) | 86 (27.56) | 73 (23.4) | 129 (41.35) |

| Pain in the extremities of the body | 37 (11.86) | 52 (16.67) | 88 (28.21) | 61 (19.55) | 74 (23.72) |

| Fatigue with ease | 17 (5.45) | 74 (23.72) | 123 (39.42) | 53 (16.99) | 45 (14.42) |

| Digestive problems | 41 (13.14) | 74 (23.72) | 90 (28.85) | 46 (14.74) | 61 (19.55) |

| Loss of appetite | 47 (15.06) | 63 (20.19) | 109 (34.94) | 47 (15.06) | 46 (14.74) |

| Increased appetite | 36 (11.54) | 88 (28.21) | 91 (29.17) | 49 (15.71) | 48 (15.38) |

| Nausea and vomiting | 109 (34.94) | 79 (25.32) | 74 (23.72) | 28 (8.97) | 22 (7.05) |

| Trembling hands | 54 (17.31) | 63 (20.19) | 101 (32.37) | 38 (12.18) | 56 (17.95) |

| Breathing problems | 117 (37.5) | 80 (25.64) | 64 (20.51) | 21 (6.73) | 30 (9.62) |

| Symptoms | Emotional Fatigue | Depersonalization | Personal Fulfillment | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | p | X2 | df | p | χ2 | df | p | |

| Enjoy activities | 25.277 | 8 | 0.001 | 12.974 | 8 | 0.113 | 22.433 | 8 | 0.004 |

| Headaches | 31.587 | 8 | 0.000 | 21.294 | 8 | 0.006 | 4.145 | 8 | 0.844 |

| Neck pain | 35.226 | 8 | 0.000 | 23.613 | 8 | 0.003 | 4.494 | 8 | 0.810 |

| Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain | 20.857 | 8 | 0.008 | 13.936 | 8 | 0.083 | 15.757 | 8 | 0.046 |

| Back and waist pain | 74.629 | 8 | 0.000 | 29.255 | 8 | 0.000 | 11.169 | 8 | 0.192 |

| Pain in the extremities of the body | 40.941 | 8 | 0.000 | 21.182 | 8 | 0.007 | 10.288 | 8 | 0.245 |

| Fatigue with ease | 54.120 | 8 | 0.000 | 24.039 | 8 | 0.002 | 17.061 | 8 | 0.029 |

| Digestive problems | 31.986 | 8 | 0.000 | 40.360 | 8 | 0.000 | 9.262 | 8 | 0.321 |

| Loss of appetite | 32.255 | 8 | 0.000 | 34.590 | 8 | 0.000 | 11.712 | 8 | 0.165 |

| Increased appetite | 15.266 | 8 | 0.054 | 3.788 | 8 | 0.876 | 8.008 | 8 | 0.433 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 26.935 | 8 | 0.001 | 18.818 | 8 | 0.016 | 7.647 | 8 | 0.469 |

| Trembling hands | 38.998 | 8 | 0.000 | 37.680 | 8 | 0.000 | 4.034 | 8 | 0.854 |

| Breathing problems | 29.224 | 8 | 0.000 | 34.646 | 8 | 0.000 | 21.056 | 8 | 0.007 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chauca-Bajaña, L.; Ordoñez Balladares, A.; Carrión Bustamante, I.A.; Sánchez Salcedo, A.C.; Suárez-Palacios, J.; Villao-León, X.A.; Morán Peña, F.J.; Egüés Cevallos, R.C.; Tolozano-Benites, R.; Velásquez Ron, B. Burnout Syndrome Among Dental Students in Clinical Training: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study in Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091393

Chauca-Bajaña L, Ordoñez Balladares A, Carrión Bustamante IA, Sánchez Salcedo AC, Suárez-Palacios J, Villao-León XA, Morán Peña FJ, Egüés Cevallos RC, Tolozano-Benites R, Velásquez Ron B. Burnout Syndrome Among Dental Students in Clinical Training: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study in Ecuador. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091393

Chicago/Turabian StyleChauca-Bajaña, Luis, Andrea Ordoñez Balladares, Ivonne Alison Carrión Bustamante, Andrea Carolina Sánchez Salcedo, Juan Suárez-Palacios, Xavier Andrés Villao-León, Francisco Jorge Morán Peña, Rita Carolina Egüés Cevallos, Roberto Tolozano-Benites, and Byron Velásquez Ron. 2025. "Burnout Syndrome Among Dental Students in Clinical Training: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study in Ecuador" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091393

APA StyleChauca-Bajaña, L., Ordoñez Balladares, A., Carrión Bustamante, I. A., Sánchez Salcedo, A. C., Suárez-Palacios, J., Villao-León, X. A., Morán Peña, F. J., Egüés Cevallos, R. C., Tolozano-Benites, R., & Velásquez Ron, B. (2025). Burnout Syndrome Among Dental Students in Clinical Training: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study in Ecuador. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091393