Race, Social Context, and Caregiving Intensity: Impact on Depressive Symptoms Among Spousal Caregivers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. HRS Population and Sample Derivation

2.3. Outcome (Depressive Symptoms)

2.3.1. Main Predictors of Interest (Care Intensity)

2.3.2. Covariates

2.3.3. Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADRD | Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias |

| HRS | Health and Retirement Study |

| RAND HRS | RAND Health and Retirement Study |

| ADLs | Activities of daily living |

| iADLs | Instrumental activities of daily living |

| ADAMS | Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study |

| CESD | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression |

| NH White | Non-Hispanic White |

| HS | High School |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| GED | General Educational Development |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| NINR | National Institute of Nursing Research |

| NIA | National Institute on Aging |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Caregiving. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/caregiving/index.html (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures Special Report: American Perspectives on Early Detection of Alzheimer’s Disease in the Era of Treatment. 2025. Available online: https://www.alz.org/getmedia/3d226bf2-0690-48d0-98ac-d790384f4ec2/alzheimers-facts-and-figures-special-report.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Hazzan, A.A.; Dauenhauer, J.; Follansbee, P.; Hazzan, J.O.; Allen, K.; Omobepade, I. Family Caregiver Quality of Life and the Care Provided to Older People Living with Dementia: Qualitative Analyses of Caregiver Interviews. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unson, C.; Njoku, A.; Bernard, S.; Agbalenyo, M. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Chronic Stress among Male Caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, A.; Thao, L.; Condon, O.; Liebzeit, D.; Fields, B. A Systematic Review of the Needs of Dementia Caregivers Across Care Settings. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2022, 34, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.; Hahn, H.; Lee, A.J.; Madison, C.A.; Atri, A. In the Information Age, Do Dementia Caregivers Get the Information They Need? Semi-Structured Interviews to Determine Informal Caregivers’ Education Needs, Barriers, and Preferences. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgdorf, J.G.; Reckrey, J.; Russell, D. “Care for Me, Too”: A Novel Framework for Improved Communication and Support Between Dementia Caregivers and the Home Health Care Team. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 874–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.; Eccleston, C.E.; Doherty, K.V.; Jang, S.; McInerney, F. Communication in Dementia Care: Experiences and Needs of Carers. Dementia 2022, 21, 1381–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, R.A.; Ponnala, S.; Younan, L.; Weiler, D.T.; Bykovskyi, A.G.; Werner, N.E. A Process-Based Approach to Exploring the Information Behavior of Informal Caregivers of People Living with Dementia. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2021, 145, 104341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Alkhamees, A.A.; Hallit, S.; Al-Dwaikat, T.N.; Khatatbeh, H.; Al-Dossary, S.A. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 8: Investigating Its Cutoff Scores in Relevance to Loneliness and Burnout among Dementia Family Caregivers. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, C.; Reis, A.; Lencastre, L. Caregiver Quality of Life: Satisfaction and Burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellis, E.; Mukaetova-Ladinska, E.B. Informal Caregiving and Alzheimer’s Disease: The Psychological Effect. Medicina 2022, 59, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, F. Examining the Relationship Between Community-Based Support Services Use and Mental Health in Black Family Caregivers of Persons Living with Dementia. Ph.D Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, E.; Wyman-Chick, K.A.; Costello, R.; Ghodsi, H.; Rivera, C.S.; Solomon, L.; Kane, J.P.M.; Litvan, I. Sex Differences for Social Determinants Associated with Lewy Body Dementia Onset and Diagnosis. Neurodegener. Dis. 2025, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikanga, J.; Reyes, A.; Zhao, L.; Hill-Jarrett, T.G.; Hammers, D.; Epenge, E.; Esambo, H.; Kavugho, I.; Esselakoy, C.; Gikelekele, G.; et al. Exploring Factors Contributing to Caregiver Burden in Family Caregivers of Congolese Adults with Suspected Dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2023, 38, e6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, J. Health Inequities: A Persistent Global Challenge from Past to Future. Int. J. Equity Health 2025, 24, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, C.A.; Tobin, K.E.; Taylor, J.L. Caregiver Burden and Its Limitations in Describing Black Caregivers’ Experience. Curr. Geriatr. Rep. 2023, 12, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Lane, S.G.; Johnson, F.U.; Tuyisenge, M.J.; Kirch, M.; Christensen, L.L.; Malani, P.N.; Solway, E.; Singer, D.C.; Kullgren, J.T.; Koumpias, A.M. Racial and Ethnic Variances in Preparedness for Aging in Place among US Adults Ages 50–80. Geriatr. Nurs. 2023, 54, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egede, L.E.; Walker, R.J.; Williams, J.S. Addressing Structural Inequalities, Structural Racism, and Social Determinants of Health: A Vision for the Future. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2024, 39, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, R.; Durkin, M.; Engward, H.; Cable, G.; Iancu, M. The Impact of Caring for Family Members with Mental Illnesses on the Caregiver: A Scoping Review. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daac049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willert, B.; Minnotte, K.L. Informal Caregiving and Strains: Exploring the Impacts of Gender, Race, and Income. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 943–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, J.C.; Hasche, L.; Bell, L.M.; Johnson, H. Exploring How Workplace and Social Policies Relate to Caregivers’ Financial Strain. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2018, 61, 849–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, C.; Biscardi, M.; Astell, A.; Nalder, E.; Cameron, J.I.; Mihailidis, A.; Colantonio, A. Sex and Gender Differences in Caregiving Burden Experienced by Family Caregivers of Persons with Dementia: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stall, N.M.; Shah, N.R.; Bhushan, D. Unpaid Family Caregiving—The Next Frontier of Gender Equity in a Postpandemic Future. JAMA Health Forum 2023, 4, e231310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnone, J. Caregiver Burden and Mental Health: Millennial Caregivers. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Wister, A.; Mitchell, B.; Li, L.; Kadowaki, L. Healthcare System Navigation Difficulties among Informal Caregivers of Older Adults: A Logistic Regression Analysis of Social Capital, Caregiving Support and Utilization Factors. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, M.; Köhler-Forsberg, O.; Turner, M.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Wrobel, A.; Firth, J.; Loughman, A.; Reavley, N.J.; McGrath, J.J.; Momen, N.C.; et al. Comorbidity between Major Depressive Disorder and Physical Diseases: A Comprehensive Review of Epidemiology, Mechanisms and Management. World Psychiatry 2023, 22, 366–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehar, U.; Rawat, P.; Choudhury, M.; Boles, A.; Culberson, J.; Khan, H.; Malhotra, K.; Basu, T.; Reddy, P.H. Comprehensive Understanding of Hispanic Caregivers: Focus on Innovative Methods and Validations. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Rep. 2023, 7, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, J.T.; Theng, B.; Serag, H.; Raji, M.; Tzeng, H.-M.; Shih, M.; Lee, W.-C. (Miso) Cultural Diversity Impacts Caregiving Experiences: A Comprehensive Exploration of Differences in Caregiver Burdens, Needs, and Outcomes. Cureus 2023, 15, e46537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziej, I.W.K.; Coe, N.B.; Van Houtven, C.H. The Impact of Care Intensity and Work on the Mental Health of Family Caregivers: Losses and Gains. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2022, 77, S98–S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Lou, W.Q.V. Continuity and Changes in Three Types of Caregiving and the Risk of Depression in Later Life: A 2-Year Prospective Study. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, G.G.; Hassan, H.; Faul, J.D.; Rodgers, W.L.; Weir, D.R. Health and Retirement Study: Imputation of Cognitive Functioning Measures, 1992–2014 (Final Release Version); Survey Research Center, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2017; Available online: https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/biblio/COGIMPdd.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Bugliari, D.; Campbell, N.; Chan, C.; Hayden, O.; Hurd, M.; Main, R.; Mallett, J.; McCullough, C.; Meijer, E.; Moldoff, M.; et al. RAND HRS Longitudinal File 1992–2018 (Version 1); RAND Center for the Study of Aging: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://hrsdata.isr.umich.edu/sites/default/files/documentation/other/1615843861/randhrs1992_2018v1.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Bugliari, D.; Campbell, N.; Chan, C.; Hayden, O.; Hurd, M.; Main, R.; Mallett, J.; McCullough, C.; Meijer, E.; Moldoff, M.; et al. RAND HRS Data File, Version P; RAND Center for the Study of Aging: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/modules/meta/rand/randhrsp/randhrs_P.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Langa, K.M.; Llewellyn, D.J.; Lang, I.A.; Weir, D.R.; Wallace, R.B.; Kabeto, M.U.; Huppert, F.A. Cognitive Health among Older Adults in the United States and in England. BMC Geriatr. 2009, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianattasio, K.Z.; Wu, Q.; Glymour, M.M.; Power, M.C. Comparison of Methods for Algorithmic Classification of Dementia Status in the Health and Retirement Study. Epidemiology 2019, 30, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnega, A.; Faul, J.D.; Ofstedal, M.B.; Langa, K.M.; Phillips, J.W.; Weir, D.R. Cohort Profile: The Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeringa, S.G.; Fisher, G.G.; Hurd, M.; Langa, K.M.; Ofstedal, M.B.; Plassman, B.L.; Rodgers, W.L.; Weir, D.R. Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS): Sample Design, Weighting and Analysis for ADAMS; University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2009; Available online: https://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/adams/ADAMSSampleWeights_Nov2007.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Perrin, N.; Li, J. Depressive Symptoms and Cognitive Function in Older Adults with Subjective Cognitive Decline: Longitudinal Findings From 2010 to 2020. Alzheimer’s Amp Dement. 2024, 20, e090034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffick, D. Documentation of Affective Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study; Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Lane, S.G. Adapting to Chronic Pain: A Focused Ethnography of Black Older Adults. Geriatr. Nurs. 2020, 41, 468–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson-Lane, S.G.; Johnson, F.U.; Tuyisenge, M.J.; Jackson, J.; Qurashi, T.; Tripathi, P.; Giordani, B. “It Isn’t What I Had to Do, It’s What I Get to Do”: The Experiences of Black Family Caregivers Managing Dementia. J. Fam. Nurs. 2024, 30, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monte, V.; Pham, M.D.; Tsai, W. Microaggressions and General Health among Black and Asian Americans: The Moderating Role of Cognitive Reappraisal. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2025, 31, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sörensen, S.; Pinquart, M. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Relationship of Caregiving Stressors, Resources, and Sociodemographic Variables to Caregiver Depression and Perceived Physical Health. Aging Ment. Health 2005, 9, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.A.; Mendez-Luck, C.A.; Greaney, M.L.; Azzoli, A.B.; Cook, S.K.; Sabik, N.J. Differences in Caregiving Intensity Among Distinct Sociodemographic Subgroups of Informal Caregivers: Joint Effects of Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Employment. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2021, 47, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losada-Baltar, A.; Falzarano, F.B.; Hancock, D.W.; Márquez-González, M.; Pillemer, K.; Huertas-Domingo, C.; Jiménez-Gonzalo, L.; Fernandes-Pires, J.A.; Czaja, S.J. Cross-National Analysis of the Associations Between Familism and Self-Efficacy in Family Caregivers of People With Dementia: Effects on Burden and Depression. J. Aging Health 2024, 36, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenteau, A.M.; Boyer, C.J.; Campos, L.J.; Carranza, A.F.; Deer, L.K.; Hartman, D.T.; Bidwell, J.T.; Hostinar, C.E. A Review of Mental Health Disparities during COVID-19: Evidence, Mechanisms, and Policy Recommendations for Promoting Societal Resilience. Dev. Psychopathol. 2023, 35, 1821–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Santos, A.-E.; Facal, D.; Vicho De La Fuente, N.; Vilanova-Trillo, L.; Gandoy-Crego, M.; Rodríguez-González, R. Gender Impact of Caring on the Health of Caregivers of Persons with Dementia. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 2165–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Category | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | NH White | 1288 | 60.98 |

| African American | 425 | 20.12 | |

| Hispanic | 243 | 11.51 | |

| Other | 156 | 7.39 | |

| Sex | Female | 1259 | 59.61 |

| Male | 853 | 40.39 | |

| Education | Less than HS | 764 | 36.17 |

| GED or HS graduate | 757 | 35.84 | |

| Some college | 358 | 16.95 | |

| College and above | 233 | 11.03 | |

| Total | 2112 | 100.00 |

| Spousal Depression | None (Mean ± SD) n = 4233 | Low (Mean ± SD) n = 931 | High (Mean ± SD) n = 1458 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 1.76 ± 2.05 | 1.96 ± 2.19 | 2.06 ± 2.18 |

| ADLs | 0.44 ± 1.01 | 0.43 ± 0.98 | 0.34 ± 0.83 |

| iADLs | 0.36 ± 0.90 | 0.32 ± 0.83 | 0.25 ± 0.68 |

| Diagnosis duration (n) | n = 2744 | n = 704 | n = 1217 |

| Diagnosis duration | 2.73 ± 3.78 | 2.77 ± 3.42 | 2.97 ± 3.75 |

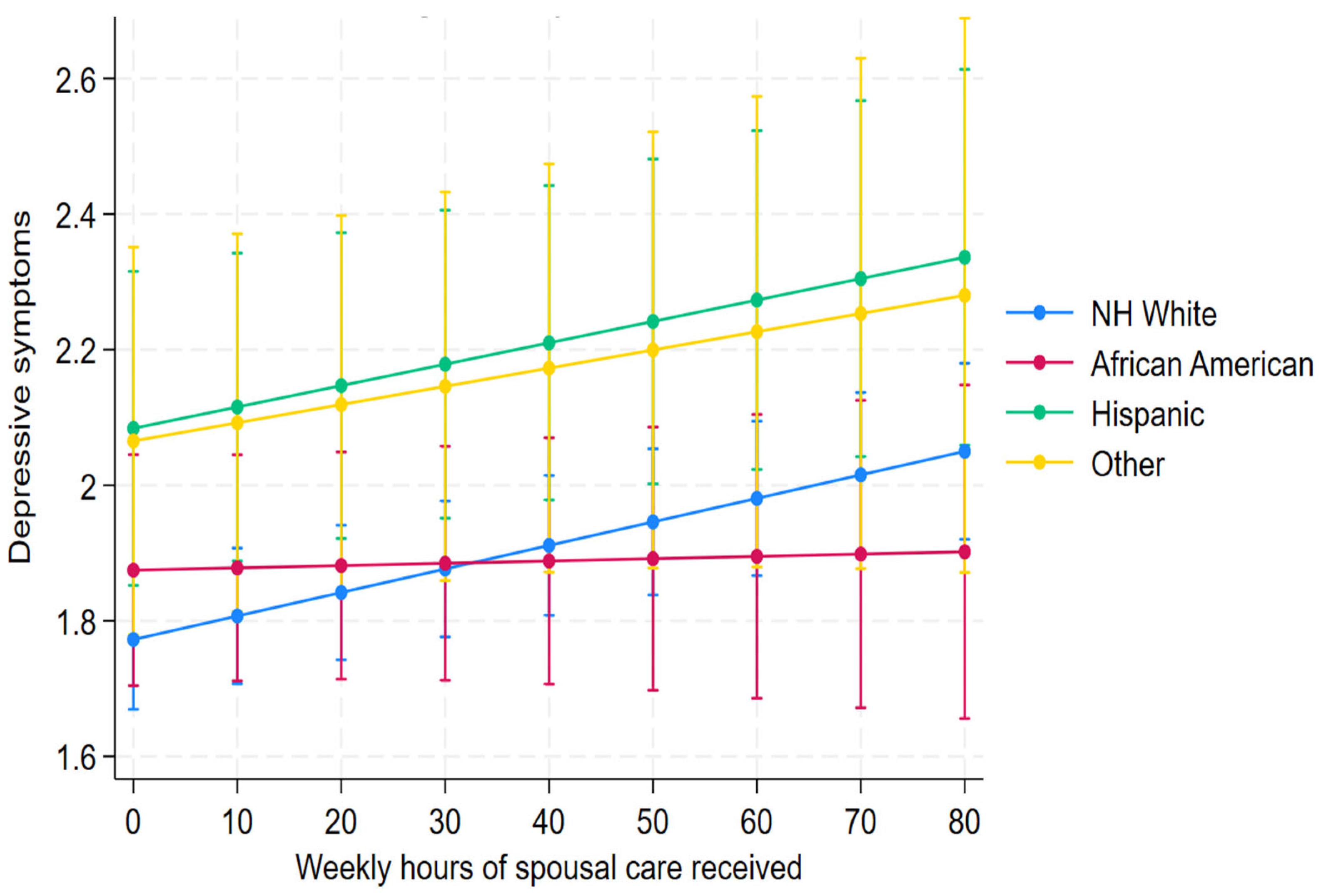

| Parameter | Estimate | Std. Err. | [95% Conf. Internal] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiving Hours (Race = African American) | −1.2499 | 0.5053 | −2.2403 to −0.2596 |

| Caregiving Hours (Race = NH White) | Ref | ||

| Caregiving Hours (Race = Hispanic) | −0.3004 | 0.5469 | −1.3724 to 0.7716 |

| Caregiving Hours (Race = Other) | −0.3780 | 0.7127 | −1.7749 to 1.0190 |

| Depressive symptoms | 2.086863 | 0.0817672 | 1.932602 to 2.253438 |

| Gender (Male) | −0.3618 | 0.9906 | −2.3034 to 1.5798 |

| White (Caregiving Hours = 0) | Ref | ||

| Black (Caregiving Hours = 0) | −0.2381 | 1.5849 | −3.3444 to 2.8682 |

| Hispanic (Caregiving Hours = 0) | 0.9564 | 2.0072 | −2.9778 to 4.8905 |

| Other (Caregiving Hours = 0) | −1.3794 | 2.4826 | −6.2452 to 3.4863 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johnson, F.U.; Plegue, M.; Boddakayala, N.; Robinson-Lane, S.G. Race, Social Context, and Caregiving Intensity: Impact on Depressive Symptoms Among Spousal Caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091379

Johnson FU, Plegue M, Boddakayala N, Robinson-Lane SG. Race, Social Context, and Caregiving Intensity: Impact on Depressive Symptoms Among Spousal Caregivers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091379

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohnson, Florence U., Melissa Plegue, Namratha Boddakayala, and Sheria G. Robinson-Lane. 2025. "Race, Social Context, and Caregiving Intensity: Impact on Depressive Symptoms Among Spousal Caregivers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091379

APA StyleJohnson, F. U., Plegue, M., Boddakayala, N., & Robinson-Lane, S. G. (2025). Race, Social Context, and Caregiving Intensity: Impact on Depressive Symptoms Among Spousal Caregivers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091379