The Impact of Different Types of Social Resources on Coping Self-Efficacy and Distress During Australia’s Black Summer Bushfires

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Social Resources and Disaster Resilience

- Defining types of social resources: cognitive vs. structural, received vs. perceived

2. Materials and Methods

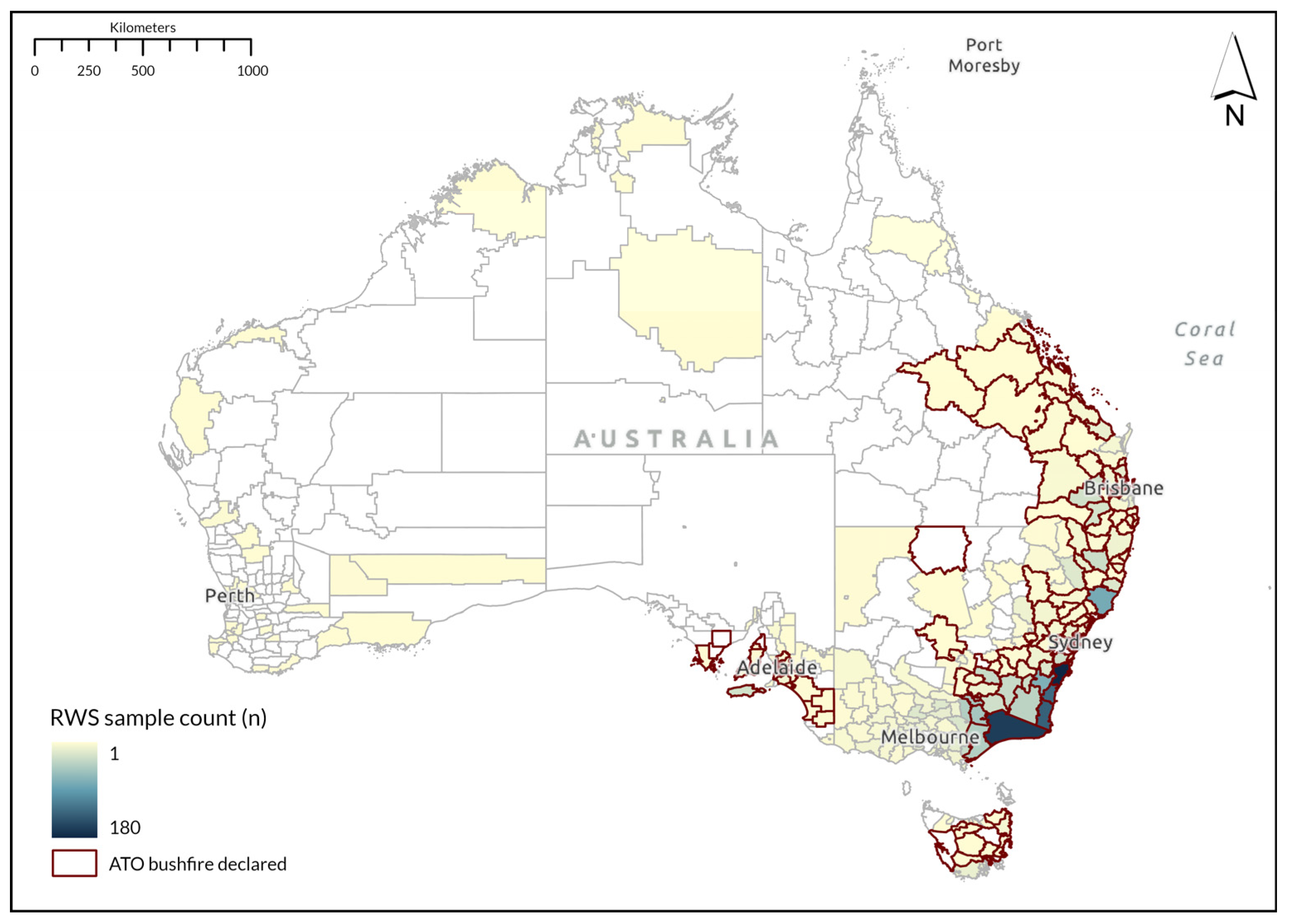

2.1. Context and Study Area

2.2. Survey Distribution

2.3. Sample

2.4. Measures

- Emotional support—a retrospective measure of perceived access to emotional support during the time the bushfires were active, measured using a single item.

- Practical support—a retrospective measure of perceived access to practical support during the time the bushfires were active, measured using a single item.

- Sense of belonging (existing scale)—a cognitive social resource that asks about sense of belonging at the time the survey was completed.

- Loneliness index—a cognitive social resource often associated with strength and depth of social networks, measured using existing validated scale and asking about loneliness at the time the survey was completed.

- Bushfire reciprocal support—a retrospective measure of reciprocal help given to and received from neighbours and other community members during the fires; as this was a new measure, EFA was used to construct a scale.

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Coping Self-Efficacy and Distress During Bushfires

3.2. Model 1: Coping Self-Efficacy During the Bushfires

3.3. Model 2: Distress During the Bushfire

4. Discussion

4.1. Coping Self-Efficacy

4.2. Distress During Bushfires

4.3. Limitations, Strengths and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baldwin, C.; Ross, H. Beyond a tragic fire season: A window of opportunity to address climate change? Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Virgilio, G.; Evans, J.P.; Clarke, H.; Sharples, J.; Hirsch, A.L.; Hart, M.A. Climate Change Significantly Alters Future Wildfire Mitigation Opportunities in Southeastern Australia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL088893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). The Sendai Framework Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction: Disaster. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/terminology/disaster (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Whittaker, J.; Taylor, M.; Bearman, C. Why don’t bushfire warnings work as intended? Responses to official warnings during bushfires in New South Wales, Australia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 45, 101476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahan, K.; Gilbert, J. Protective Decision-Making in Bushfire Part 1: A Rapid Systematic Review of the ‘Wait and See’ Literature. Fire 2021, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, E.; Heffernan, T.; Greenwood, L.M.; Walker, I.; Lane, J.; Stanley, S.K.; Evans, O.; Calear, A.L.; Cruwys, T.; Christensen, B.K.; et al. Predictors of individual mental health and psychological resilience after Australia’s 2019-2020 bushfires. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2024, 58, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S. Evolution of Recovery Studies and Recovery Duration. In The Routledge Handbook of Disaster Response and Recovery; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2025; pp. 314–330. [Google Scholar]

- Beaglehole, B.; Mulder, R.T.; Frampton, C.M.; Boden, J.M.; Newton-Howes, G.; Bell, C.J. Psychological distress and psychiatric disorder after natural disasters: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.A.; Waters, E.; Gibbs, L.; Gallagher, H.C.; Pattison, P.; Lusher, D.; MacDougall, C.; Harms, L.; Block, K.; Snowdon, E.; et al. Psychological outcomes following the Victorian Black Saturday bushfires. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çifçi, S.; Kilinç, Z. The Disaster of the Century: Effects of the 6 February 2023 Kahramanmaraş Earthquakes on the Sleep and Mental Health of Healthcare Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedy, J.R.; Saladin, M.E.; Kilpatrick, D.G.; Resnick, H.S.; Saunders, B.E. Understanding acute psychological distress following natural disaster. J. Trauma. Stress 1994, 7, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedy, J.R.; Shaw, D.L.; Jarrell, M.P.; Masters, C.R. Towards an understanding of the psychological impact of natural disasters: An application of the conservation resources stress model. J. Trauma. Stress 1992, 5, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, M.; Bordelois, P.M.; Galea, S.; Norris, F.; Tracy, M.; Koenen, K.C. The course of posttraumatic stress symptoms and functional impairment following a disaster: What is the lasting influence of acute versus ongoing traumatic events and stressors? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massazza, A.; Brewin, C.R.; Joffe, H. Feelings, Thoughts, and Behaviors During Disaster. Qual. Health Res. 2021, 31, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, J.; Elliott, G.; Omodei, M.M. Householder decision-making under imminent wildfire threat: Stay and defend or leave? Int. J. Wildland Fire 2012, 21, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, D.J.; Lang, I.A.; Langa, K.M.; Huppert, F.A. Cognitive function and psychological well-being: Findings from a population-based cohort. Age Ageing 2008, 37, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, K.E.; Su, L.J.; Welsh, D.A.; Galea, S.; Jazwinski, S.M.; Silva, J.L.; Erwin, M.J. Cognitive and Psychosocial Consequences of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita Among Middle-Aged, Older, and Oldest-Old Adults in the Louisiana Healthy Aging Study (LHAS). J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 2463–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Li, B.; Hikichi, H.; Kawachi, I.; Li, X. Long-Term Trajectories of Cognitive Disability Among Older Adults Following a Major Disaster. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2448277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, R.S.; Schneider, J.A.; Boyle, P.A.; Arnold, S.E.; Tang, Y.; Bennett, D.A. Chronic distress and incidence of mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 2007, 68, 2085–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Traumatic stress: A theory based on rapid loss of resources. Anxiety Res. 1991, 4, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. Conservation of Resources Theory: Its Implication for Stress, Health, and Resilience. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Folkman, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, F.H.; Murrell, S.A. Protective function of resources related to life events, global stress, and depression in older adults. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1984, 25, 424–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Exercise of personal agency through the self-efficacy mechanism. In Self-Efficacy: Thought Control of Action; Hemisphere Publishing Corp.: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. On the Functional Properties of Perceived Self-Efficacy Revisited. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benight, C.C.; Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004, 42, 1129–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benight, C.C.; Shoji, K.; James, L.E.; Waldrep, E.E.; Delahanty, D.L.; Cieslak, R. Trauma Coping Self-Efficacy: A Context-Specific Self-Efficacy Measure for Traumatic Stress. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2015, 7, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karademas, E.C.; Kalantzi-Azizi, A. The stress process, self-efficacy expectations, and psychological health. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 37, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuth, J.L.; Morss, R.; Lazo, J.; Trumbo, C. The effects of past hurricane experiences on evacuation intentions through risk perception and efficacy beliefs: A mediation analysis. Weather Clim. Soc. 2016, 8, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, D. Disaster preparedness: A social-cognitive perspective. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2003, 12, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, D.; Millar, M.; Johnston, D. Community Resilience to Volcanic Hazard Consequences. Nat. Hazards 2001, 24, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, J.; Cowlishaw, S.; Paton, D.; Beatson, R.; Elliott, G. Predictors of south-eastern Australian householders’ strengths of intentions to self-evacuate if a wildfire threatens: Two theoretical models. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2014, 23, 1176–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newnham, E.A.; Balsari, S.; Lam, R.P.K.; Kashyap, S.; Pham, P.; Chan, E.Y.Y.; Patrick, K.; Leaning, J. Self-efficacy and barriers to disaster evacuation in Hong Kong. Int. J. Public Health 2017, 62, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benight, C.C.; Swift, E.; Sanger, J.; Smith, A.; Zeppelin, D. Coping Self-Efficacy as a Mediator of Distress Following a Natural Disaster. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2443–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benight, C.C.; Harper, M.L. Coping self-efficacy perceptions as a mediator between acute stress response and long-term distress following natural disasters. J. Trauma. Stress 2002, 15, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benight, C.C.; Ironson, G.; Klebe, K.; Carver, C.S.; Wynings, C.; Burnett, K.; Greenwood, D.; Baum, A.; Schneiderman, N. Conservation of resources and coping self-efficacy predicting distress following a natural disaster: A causal model analysis where the environment meets the mind. Anxiety Stress Coping 1999, 12, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing Conservation of Resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Kaniasty, K. Received and perceived social support in times of stress: A test of the social support deterioration deterrence model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.; Pfefferbaum, B.; Wyche, K.; Pfefferbaum, R. Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paton, D. Disaster risk reduction: Psychological perspectives on preparedness. Aust. J. Psychol. 2019, 71, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riad, J.K.; Norris, F.H.; Ruback, R.B. Predicting Evacuation in Two Major Disasters: Risk Perception, Social Influence, and Access to Resources. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 918–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruwys, T.; Macleod, E.; Heffernan, T.; Walker, I.; Stanley, S.K.; Kurz, T.; Greenwood, L.-M.; Evans, O.; Calear, A.L. Social group connections support mental health following wildfire. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 59, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, R.A.; Gallagher, H.C.; Gibbs, L.; Pattison, P.; MacDougall, C.; Harms, L.; Block, K.; Baker, E.; Sinnott, V.; Ireton, G.; et al. Mental Health and Social Networks After Disaster. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 174, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuire, A.P.; Gauthier, J.M.; Anderson, L.M.; Hollingsworth, D.W.; Tracy, M.; Galea, S.; Coffey, S.F. Social Support Moderates Effects of Natural Disaster Exposure on Depression and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms: Effects for Displaced and Nondisplaced Residents. J. Trauma. Stress 2018, 31, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, P.A. Mechanisms Linking Social Ties and Support to Physical and Mental Health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2011, 52, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sippel, L.M.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Charney, D.S.; Mayes, L.C.; Southwick, S.M. How does social support enhance resilience in the trauma-exposed individual? Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Knoll, N. Functional roles of social support within the stress and coping process: A theoretical and empirical overview. Int. J. Psychol. 2007, 42, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P.; Meyer, M.A. Social Capital and Community Resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatson, R.; McLennan, J. What Applied Social Psychology Theories Might Contribute to Community Bushfire Safety Research After Victoria’s “Black Saturday”. Aust. Psychol. 2011, 46, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, N.; Gladwin, H. Evacuation Decision Making and Behavioral Responses: Individual and Household. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2007, 8, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovreglio, R.; Ronchi, E.; Nilsson, D. An Evacuation Decision Model based on perceived risk, social influence and behavioural uncertainty. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2016, 66, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, M.; Murata, A. Social Capital Encourages Disaster Evacuation: Evidence from a Cyclone in Bangladesh. J. Dev. Stud. 2021, 57, 790–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniasty, K.; Norris, F.H. A test of the social support deterioration model in the context of natural disaster. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R.L.; Maurer, K. Bonding, bridging and linking: How social capital operated in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina. Br. J. Soc. Work 2010, 40, 1777–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Shaw, R. Social Capital: A Missing Link to Disaster Recovery. Int. J. Mass Emergencies Disasters 2004, 22, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Galea, S.; Bucciarelli, A.; Vlahov, D. What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 75, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Friedman, M.J.; Watson, P.J.; Byrne, C.M.; Diaz, E.; Kaniasty, K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry 2002, 65, 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.; Ersing, R.; Polen, A.; Saunders, M.; Senkbeil, J. The Effects of Social Connections on Evacuation Decision Making during Hurricane Irma. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 10, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbert, J.S.; Haines, V.a.; Beggs, J.J. Core Networks and Tie Activation: What Kinds of Routine Networks Allocate Resources in Nonroutine Situations? Am. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 65, 598–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniasty, K.; Norris, F. Distinctions that Matter: Received Social Support, Perceived Social Support, and Social Embeddedness after Disasters. In Mental Health and Disasters; Neria, Y., Galea, S., Norris, F.H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Touchstone Books/Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, S.; Carpiano, R.M. Measures of personal social capital over time: A path analysis assessing longitudinal associations among cognitive, structural, and network elements of social capital in women and men separately. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 257, 112172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almedom, A.M. Social capital and mental health: An interdisciplinary review of primary evidence. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 943–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, H.L.; Welsh, J.A. Social capital and health in Australia: An overview from the household, income and labour dynamics in Australia survey. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, M. Distinctions Between Social Support Concepts, Measures, and Models. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 413–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkel-Schetter, C.; Bennett, T.L. Differentiating the cognitive and behavioral aspects of social support. In Social Support: An Interactional View; Sarason, I., Sarason, G., Pierce, G.R., Eds.; Wiley Series on Personality Processes; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990; pp. 267–296. [Google Scholar]

- Paton, D.; Tedim, F. Enhancing Forest Fires Preparedness in Portugal: Integrating Community Engagement and Risk Management. Planet@ Risk 2014, 1, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mileti, D.; Sorensen, J. Communication of Emergency Public Warnings: A Social Science Perspective and State-of-the-ART Assessment; Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, V.A.; Beggs, J.J.; Hurlbert, J.S. Exploring the structural contexts of the support process: Social networks, social statuses, social support, and psychological distress. In Social Networks and Health, Advances in Medical Sociology; Levy, J.A., Pescosolido, B.A., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2002; Volume 8, pp. 269–292. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, O.; Weil, F.; Patel, K. The Role of Community in Disaster Response: Conceptual Models. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2010, 29, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, A.M.; Ukkusuri, S.V.; Gladwin, H. Modeling joint evacuation decisions in social networks: The case of Hurricane Sandy. J. Choice Model. 2017, 25, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.F.; Fraustino, J.D.; Jin, Y. Social Media Use During Disasters: How Information Form and Source Influence Intended Behavioral Responses. Commun. Res. 2016, 43, 626–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenman, D.P.; Cordasco, K.M.; Asch, S.; Golden, J.F.; Glik, D. Disaster planning and risk communication with vulnerable communities: Lessons from Hurricane Katrina. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97 (Suppl. 1), S109–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrison, M.E.B.; Sasser, D.D. Families and Disasters: Making Meaning out of Adversity. In Lifespan Perspectives on Natural Disasters: Coping with Katrina, Rita, and Other Storms; Cherry, K.E., Ed.; Springer US: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty, K.; Norris, F.H. In search of altruistic community: Patterns of social support mobilization following Hurricane Hugo. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 447–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcicky, P.; Seebauer, S. The two faces of social capital in private flood mitigation: Opposing effects on risk perception, self-efficacy and coping capacity. J. Risk Res. 2017, 20, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokszczanin, A. Social support provided by adolescents following a disaster and perceived social support, sense of community at school, and proactive coping. Anxiety Stress Coping 2012, 25, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnberg, F.K.; Hultman, C.M.; Michel, P.-O.; Lundin, T. Social Support Moderates Posttraumatic Stress and General Distress After Disaster. J. Trauma. Stress 2012, 25, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, F.; Kaniasty, K.; Cowlishaw, S.; Wade, D.; Ma, H.; Forbes, D. Social support following a natural disaster: A longitudinal study of survivors of the 2013 Lushan earthquake in China. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 273, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weems, C.F.; Watts, S.E.; Marsee, M.A.; Taylor, L.K.; Costa, N.M.; Cannon, M.F.; Carrion, V.G.; Pina, A.A. The psychosocial impact of Hurricane Katrina: Contextual differences in psychological symptoms, social support, and discrimination. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; Smith, E.M.; Lee Robins, N.; Fischbach, R.L. Social Involvement as a Mediator of Disaster-Induced Stress. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 17, 1092–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniasty, K.; van der Meulen, E. Impact of COVID-19 on psychological distress in subsequent stages of the pandemic: The role of received social support. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaalberg, R.; Midden, C.; Meijnders, A.; McCalley, T. Prevention, adaptation, and threat denial: Flooding experiences in the Netherlands. Risk Anal. 2009, 29, 1759–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filkov, A.I.; Ngo, T.; Matthews, S.; Telfer, S.; Penman, T.D. Impact of Australia’s catastrophic 2019/20 bushfire season on communities and environment. Retrospective analysis and current trends. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2020, 1, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemter, M.; Fischer, M.; Luna, L.; Schönfeldt, E.; Vogel, J.; Banerjee, A.; Korup, O.; Thonicke, K. Cascading Hazards in the Aftermath of Australia’s 2019/2020 Black Summer Wildfires. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Taxation Office (ATO). Bushfire Declared Local Government Areas 2019-20; Australian Taxation Office: Canberra, Australia, 2020.

- Schouten, B.; Cobben, F.; Bethlehem, J. Indicators for the Representativeness of Survey Response. Surv. Methodol. 2008, 35, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 2021 Census of Population and Housing. 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/microdata-tablebuilder/available-microdata-tablebuilder/census-population-and-housing (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Cheung, K.L.; ten Klooster, P.M.; Smit, C.; de Vries, H.; Pieterse, M.E. The impact of non-response bias due to sampling in public health studies: A comparison of voluntary versus mandatory recruitment in a Dutch national survey on adolescent health. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; White, I.R.; Carlin, J.B.; Spratt, M.; Royston, P.; Kenward, M.G.; Wood, A.M.; Carpenter, J.R. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. Bmj 2009, 338, b2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys: Results From Two Population-Based Studies. Res. Aging 2004, 26, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews-Ewald, M.R.; Zullig, K.J. Evaluating the performance of a short loneliness scale among college students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2013, 54, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.; Fidell, L. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. An Index of Factorial Simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.S. A Note on the Multiplying Factors for Various χ2 Approximations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1954, 16, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, J.M.; Edwards, B. Gender and Evacuation: A Closer Look at Why Women are More Likely to Evacuate for Hurricanes. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2002, 3, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, V.M.; Roder, G.; Öcal, A.; Tarolli, P.; Dragićević, S. The Role of Gender in Preparedness and Response Behaviors towards Flood Risk in Serbia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, F.H.; Smith, T.; Kaniasty, K. Revisiting the Experience–Behavior Hypothesis: The Effects of Hurricane Hugo on Hazard Preparedness and Other Self-Protective Acts. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2010, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanujaya, B.; Prahmana, R.; Mumu, J. Likert Scale in Social Sciences Research: Problems and Difficulties. FWU J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 16, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; North American ed.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A.F.; Finan, C. Linear regression and the normality assumption. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 98, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowerman, B.L.; O’Connell, R.T. Linear Statistical Models; Thomson Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, C.C.; Brainard, J.; Innes, A.; Hunter, P.R. (Re-) conceptualising vulnerability as a part of risk in global health emergency response: Updating the pressure and release model for global health emergencies. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 2019, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisner, B. DRR pioneers: Interview with Ben Wisner. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2024, 34, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, B.G.; Gatz, M.; Heller, K.; Bengtson, V.L. Age and emotional response to the Northridge earthquake: A longitudinal analysis. Psychol. Aging 2000, 15, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D. Fixing Recovery: Social Capital in Post-Crisis Resilience. Political Science Faculty Publications 2010, 6. Available online: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/pspubs/3 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Harms, L.; Molyneaux, R.; Nguyen, H.; Pope, D.; Block, K.; Gallagher, H.C.; Kavanagh, S.A.; Quinn, P.; O’Donnell, M.; Gibbs, L. Individual and community experiences of posttraumatic growth after disaster: 10 years after the Australian Black Saturday bushfires. Psychol. Trauma. 2024, 16, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutrona, C.; Russell, D. Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. In Social Support: An Interactional View; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Rini, C.; Redd, W.H.; Austin, J.; Mosher, C.E.; Meschian, Y.M.; Isola, L.; Scigliano, E.; Moskowitz, C.H.; Papadopoulos, E.; Labay, L.E.; et al. Effectiveness of partner social support predicts enduring psychological distress after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 79, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristic | n | % of Total Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Housing type | Own house outright | 1424 | 54.5 |

| Live in a house with mortgage | 787 | 30.1 | |

| Renting | 308 | 11.8 | |

| Live in family’s home without paying rent | 73 | 2.8 | |

| Household type | Sole person household | 507 | 19.4 |

| Couple-only household | 1153 | 44.2 | |

| Couple parent with children household | 605 | 23.2 | |

| Single parent with children household | 126 | 4.8 | |

| Share or group household | 94 | 3.6 | |

| Other household type | 126 | 4.8 | |

| Household financial prosperity | Very poor | 26 | 1.0 |

| Poor | 87 | 3.3 | |

| Just getting along | 606 | 23.2 | |

| Reasonably comfortable | 1229 | 47.1 | |

| Very comfortable | 591 | 22.6 | |

| Prosperous | 54 | 2.1 |

| Measure | Survey Items/Description of Scale | Response Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||

| Age | How old are you? | Responses in individual years from ‘Under 18 years’ (excluded from analysis) to ‘100 or older’. |

| Gender | Do you identify as… | Female; male; other (e.g., non-binary, gender-fluid, no gender); prefer not to answer. Responses to ‘female’ and ‘male’ only were used in this paper due to low sample size for other responses. |

| Self-rated bushfire impact | ||

| Overall, how much were you and your household affected by any of the following in the last 12 months: Bushfire | 7-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all affected) to 7 (very severely affected). | |

| Dependent Variables | ||

| Coping self-efficacy * | Three positively worded items formed the coping self-efficacy scale as the result of EFA (Table 3). The scale measures people’s retrospective confidence in making decisions about what to do, as well as how to protect themselves and their families and prepare for potential negative bushfire impacts, a form of self-efficacy in responding during the bushfires. High coping self-efficacy scores are theorised to indicate high levels of these psychological resources. Reliability analysis indicated that the scale had acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.76, see Table 3) [95]. | The overall scale score was created by averaging the responses to three items, rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) in response to the following question: ‘How much do the following statements reflect how you felt during the period when bushfires were active’. |

| Distress during bushfire | Based on EFA, six negatively worded items formed a scale of negative psychological response experiences, which we named ‘distress during bushfire’. The six survey items were retrospective measures that asked about participant’s anxiety, sleeplessness and feelings of helplessness in protecting themselves and reducing their fire risk during the bushfires (see Table 3). This scale was theorised to measure psychological distress and perceived coping capacity related to bushfire response, and high scores reflect low levels of psychological resources that assist in responding. The scale showed high internal consistency according to Cronbach’s Alpha (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.86, see Table 3). | The overall scale score was created by averaging the responses to the six items, measured from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) in response to the following question: ‘How much do the following statements reflect how you felt during the period when bushfires were active’. |

| Social resources | ||

| Sense of belonging | The three-item sense of belonging scale used in the RWS was adapted from a scale published by Berry and Welsh [68]: I feel welcome here; I feel part of the community here; I feel like an outsider here (reversed). The scale was theorised to measure sense of belonging in community and demonstrates strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.86) [95,96]. Overall scale score was created by averaging the responses to items. | The overall score was calculated by averaging the responses on three items, measures on a 7-point scale 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). |

| Bushfire reciprocal support | Based on EFA, the bushfire reciprocal support scale was formed using three RWS items specific to the experience of receiving and providing support during the bushfires (Table 3). The scales were calculated using the average of the individual survey items. Reliability analysis suggested that the scale had acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.74) | The overall scale score was created by averaging the responses to the three items, measured from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) in response to the following question: ‘How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements about how people in your LOCAL COMMUNITY have responded during and since the bushfires?’. |

| Emotional support | Single item: I had access to emotional support if I needed it, e.g., people I could talk to. | 7-point scale 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) in response to the following question: ‘How much do the following statements reflect how you felt during the period when bushfires were active’. |

| Practical support | Single item: I had access to practical support when I needed it, e.g., help getting my property prepared for fire. | 7-point scale 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) in response to the following question: ‘How much do the following statements reflect how you felt during the period when bushfires were active’. |

| Loneliness index | The loneliness measure used was a validated three-item scale, which has been used in multiple studies and has shown acceptable reliability [97,98]. The scale had high internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.89) and was created by averaging the responses to the following three loneliness items: ‘How often do you feel that you lack companionship?’; ‘How often do you feel left out?’; ‘How often do you feel isolated from others?’. | The overall score was calculated by averaging the responses on three items measured on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (all of the time). |

| Items on Scale | Factor Loadings | Component Eigenvalue | Variance Explained | Cronbach’s α | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coping self-efficacy (DV, IV) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2.20 | 18.28 | 0.76 |

| I always or almost always felt confident to make decisions about what to do (R) | −0.62 | |||||

| I felt confident I knew how to keep my loved ones safe (R) | −0.92 | |||||

| I felt confident I could cope with the impacts of bushfire and smoke on my work or income (R) | −0.65 | |||||

| Distress during bushfire (DV) | 4.22 | 35.13 | 0.86 | |||

| I often felt anxious or worried | 0.80 | |||||

| I sometimes found it hard to concentrate on anything | 0.83 | |||||

| I had periods of time where I slept poorly or had few hours of sleep | 0.67 | 0.13 | ||||

| I sometimes felt helpless to do anything to do anything to help people or places I care about | 0.77 | −0.10 | ||||

| I sometimes felt there was nothing I could do to reduce the impacts of smoke on my household | 0.67 | |||||

| I sometimes felt there was nothing I could do to reduce the risk of fire causing damage to my home or house | 0.57 | |||||

| Bushfire reciprocal support (IV) | 1.34 | 11.20 | 7.6 | |||

| My neighbours and I helped each other out during the fires | 0.79 | |||||

| I was able to help others in my community during the fires | 0.63 | |||||

| I received help from others in my local community during the bushfires | 0.71 | |||||

| Variables Measured on 7-Point Scale | Mean Score (1–7) | % Response | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (Score of 1–3) | Moderate (Score of 4) | High (Score of 5–7) | ||

| Distress during bushfire (DV) | 4.27 | 40.4 | 21.0 | 38.5 |

| Coping self-efficacy (DV) | 4.80 | 24.9 | 21.1 | 54.0 |

| Practical support | 4.22 | 34.7 | 17.6 | 47.7 |

| Emotional support | 4.75 | 23.8 | 14.6 | 61.6 |

| Bushfire reciprocal support | 4.45 | 30.9 | 24.7 | 44.4 |

| Sense of belonging | 5.65 | 9.7 | 13.7 | 76.8 |

| Loneliness * | 2.44 | 63.8 | 26.9 | 9.3 |

| Self-rated bushfire impact | 4.26 | 35.3 | 15.3 | 49.4 |

| Variable | 2. Distress During Bushfire | 3. Practical Support | 4. Emotional Support | 5. Bushfire Reciprocal Support | 6. Sense of Belonging | 7. Loneliness | 8. Age | 8. Gender | 9. Self-Rated Bushfire Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Coping self-efficacy | −0.36 *** | 0.34 ** | 0.38 *** | 0.09 *** | 0.15 *** | −0.19 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.26 *** | −0.09 *** |

| 2. Distress during bushfire | −0.05 * | −0.06 ** | 0.20 *** | −0.10 *** | 0.28 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.26 *** | 0.37 *** | |

| 3. Practical support | 0.53 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.19 *** | −0.15 *** | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||

| 4. Emotional support | 0.20 *** | 0.27 *** | −0.25 *** | 0.08 *** | −0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| 5. Bushfire reciprocal support | 0.23 *** | −0.10 *** | −0.02 | −0.04 * | 0.27 *** | ||||

| 6. Sense of belonging | −0.39 ** | 0.26 *** | 0.01 | 0.03 | |||||

| 7. Loneliness | −0.26 *** | −0.11 *** | 0.04 | ||||||

| 7. Age | 0.21 *** | 0.04 * | |||||||

| 8. Gender | −0.06 ** |

| Variable | B[95% CI] | Beta | Sr2 | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||

| Age | 0.00 [−0.00, 0.01] | 0.04 | 0.00 | 2.07 |

| Gender | 0.73 *** [0.62, 0.85] | 0.24 | 0.06 | 12.51 |

| Self-rated bushfire impact | −0.07 *** [−0.10, −0.04] | −0.09 | 0.01 | −4.69 |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Age | 0.00 [−0.00, 0.01] | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.46 |

| Gender | 0.74 *** [0.62, 0.83] | 0.24 | 0.05 | 13.52 |

| Self-rated bushfire impact | −0.07 *** [−0.10, −0.04] | −0.09 | 0.01 | −4.92 |

| Practical support | 0.15 *** [0.11, 0.18] | 0.19 | 0.02 | 9.08 |

| Emotional support | 0.20 *** [0.17, 0.24] | 0.25 | 0.04 | 12.05 |

| Bushfire reciprocal support | 0.01 [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.28 |

| Sense of belonging | 0.01 [−0.03, 0.06] | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.61 |

| Loneliness | −0.09 ** [−0.15, −0.03] | −0.06 | 0.00 | −3.03 |

| Variable | B[95% CI] | Beta | Sr2 | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||

| Age | −0.01 *** [−0.02, −0.01] | −0.12 | 0.01 | −6.52 |

| Gender | −0.73 *** [−0.84, −0.61] | −0.22 | 0.04 | −12.10 |

| Self-rated bushfire impact | 0.32 *** [0.29, 0.35] | 0.36 | 0.13 | 20.42 |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Age | −0.01 * [−0.01, −0.00] | −0.04 | 0.00 | −2.32 |

| Gender | −0.43 *** [−0.55, −0.32] | −0.13 | 0.01 | −7.64 |

| Self-rated bushfire impact | 0.25 *** [0.22, 0.28] | 0.28 | 0.07 | 16.70 |

| Practical support | 0.02 [−0.02, 0.05] | 0.02 | 0.00 | 1.06 |

| Emotional support | 0.07 *** [0.03, 0.10] | 0.08 | 0.00 | 3.81 |

| Bushfire reciprocal support | 0.15 *** [0.12, 0.19] | 0.16 | 0.02 | 9.09 |

| Sense of belonging | −0.07 ** [−0.11, −0.02] | −0.05 | 0.00 | −2.76 |

| Loneliness | 0.35 *** [0.29, 0.41] | 0.21 | 0.03 | 11.69 |

| Coping self-efficacy | −0.32 *** [−0.36, −0.28] | −0.31 | 0.07 | −16.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amorsen, G.; Schirmer, J.; Mylek, M.R.; Niyonsenga, T.; Paton, D.; Buergelt, P.; Brown, K. The Impact of Different Types of Social Resources on Coping Self-Efficacy and Distress During Australia’s Black Summer Bushfires. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091341

Amorsen G, Schirmer J, Mylek MR, Niyonsenga T, Paton D, Buergelt P, Brown K. The Impact of Different Types of Social Resources on Coping Self-Efficacy and Distress During Australia’s Black Summer Bushfires. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091341

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmorsen, Greta, Jacki Schirmer, Mel R Mylek, Theo Niyonsenga, Douglas Paton, Petra Buergelt, and Kimberly Brown. 2025. "The Impact of Different Types of Social Resources on Coping Self-Efficacy and Distress During Australia’s Black Summer Bushfires" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091341

APA StyleAmorsen, G., Schirmer, J., Mylek, M. R., Niyonsenga, T., Paton, D., Buergelt, P., & Brown, K. (2025). The Impact of Different Types of Social Resources on Coping Self-Efficacy and Distress During Australia’s Black Summer Bushfires. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091341