Reducing Barriers for Best Practice in People Living with Dementia: Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Content Validity of the Brazilian Version of the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC-15) Meta-Tool

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Translation and Cultural Adaptation

2.2. Content Validation

2.2.1. Sample

2.2.2. Procedures

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. PAIC-15 Translation and Participants’ Characteristics

3.2. PAIC-15 Content Validation

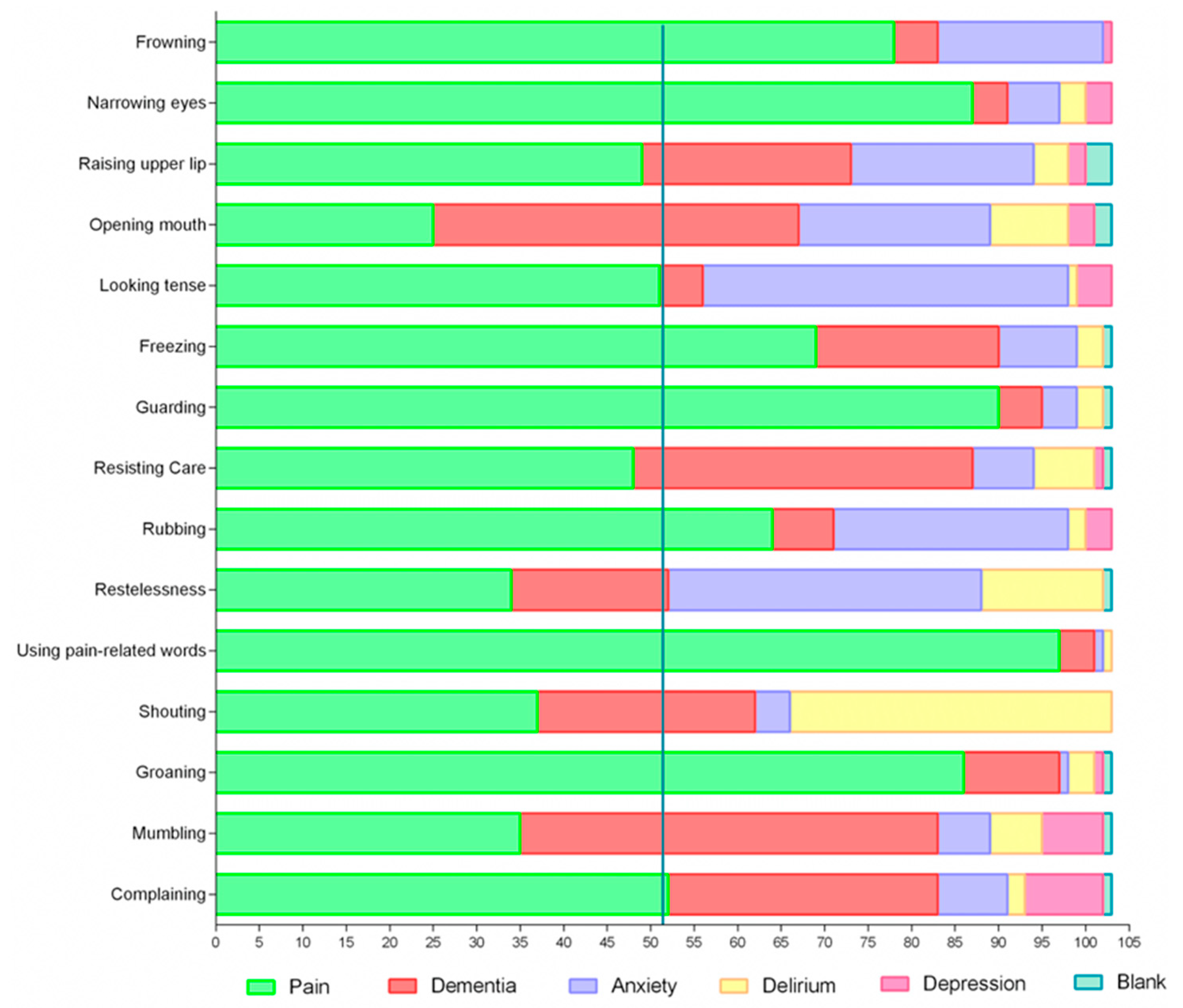

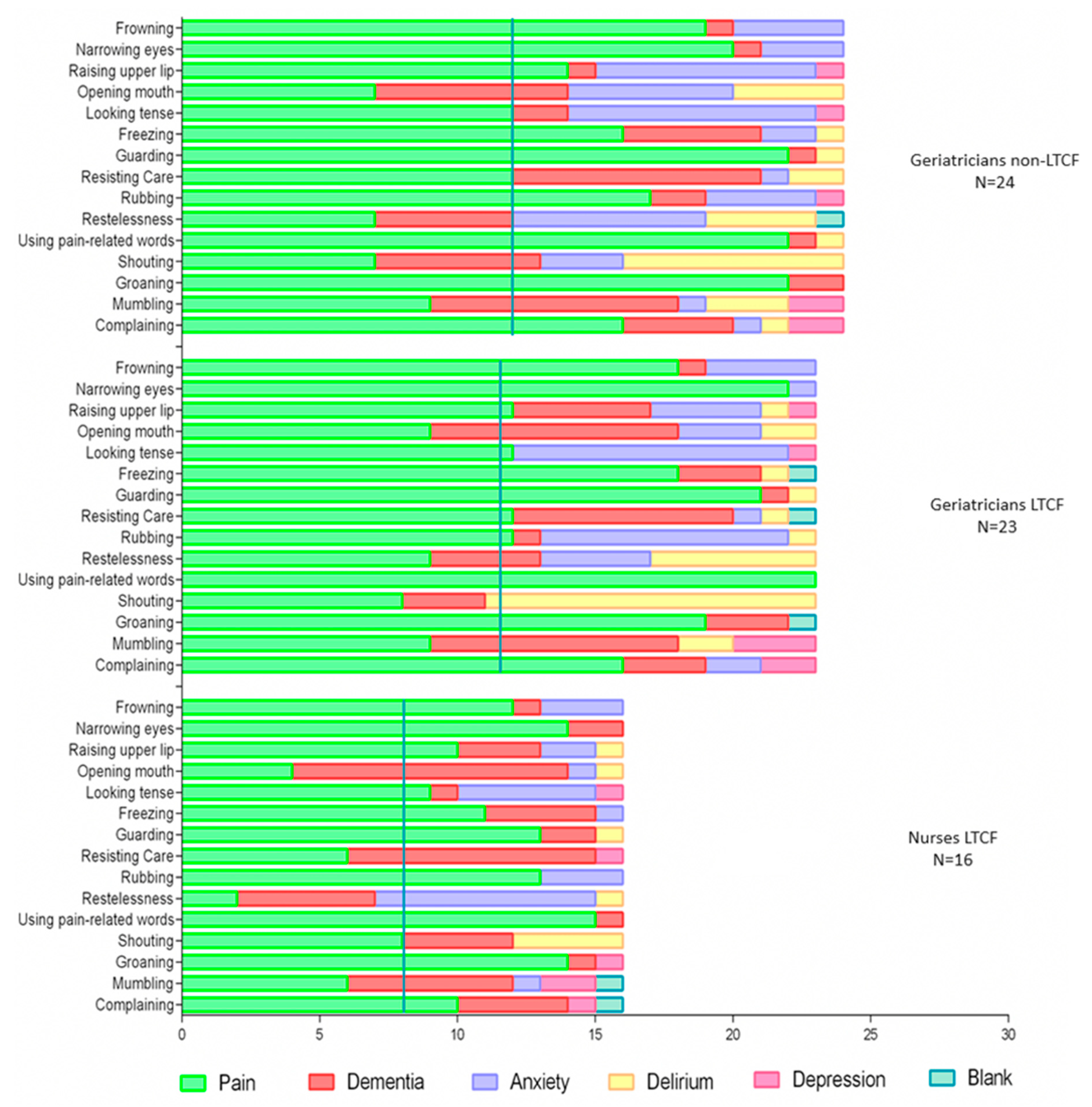

3.2.1. Facial Expressions

3.2.2. Body Movement

3.2.3. Vocalization

3.3. Agreement Between the Brazilian and the Dutch Versions of PAIC-15

3.4. Open-Ended Questions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAIC-15 | Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition |

| LTCF | Long-term Care Facilities |

| HCP | Healthcare Professionals |

| PLWD | People Living With Dementia |

| CVC | Content Validation Coefficient |

References

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Borsheski, R.; Johnson, Q.L. Pain management in the geriatric population. Mo. Med. 2014, 111, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdulla, A.; Adams, N.; Bone, M.; Elliott, A.M.; Gaffin, J.; Jones, D.; Knaggs, R.; Martin, D.; Sampson, L.; Schofield, P.; et al. Guidance on the management of pain in older people. Age Ageing 2013, 42 (Suppl. 1), i1–i57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.J.; Jao, Y.L.; Berish, D.; Hin, A.S.; Wangi, K.; Kitko, L.; Mogle, J.; Boltz, M. A Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitators of Pain Management in Persons with Dementia. J. Pain 2023, 24, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, T.; Young, Y.; Hsu, W.H. Do Nursing Home Residents With Dementia Receive Pain Interventions? Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dementiasr 2019, 34, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Van Kooten, J.; Smalbrugge, M.; van der Wouden, J.C.; Stek, M.L.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M. Prevalence of Pain in Nursing Home Residents: The Role of Dementia Stage and Dementia Subtypes. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, J.T.; Harwood, R.H.; Cowley, A.; Di Lorito, C.; Ferguson, E.; Minicucci, M.F.; Howe, L.; Masud, T.; Ogliari, G.; O’Brien, R.; et al. Chronic pain in people living with dementia: Challenges to recognising and managing pain, and personalising intervention by phenotype. Age Ageing 2023, 52, afac306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.J.; Parajuli, J.; Jao, Y.L.; Kitko, L.; Berish, D. Non-pharmacological interventions for pain in people with dementia: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 124, 104082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horgas, A.L.; Elliott, A.F.; Marsiske, M. Pain assessment in persons with dementia: Relationship between self-report and behavioral observation. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009, 57, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Herr, K.; Coyne, P.J.; Key, T.; Manworren, R.; McCaffery, M.; Merkel, S.; Pelosi-Kelly, J.; Wild, L.; American Society for Pain Management Nursing. Pain assessment in the nonverbal patient: Position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2006, 7, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtner, V.; Dowding, D.; Esterhuizen, P.; Closs, S.J.; Long, A.F.; Corbett, A.; Briggs, M. Pain assessment for people with dementia: A systematic review of systematic reviews of pain assessment tools. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Corbett, A.; Achterberg, W.; Husebo, B.; Lobbezoo, F.; de Vet, H.; Kunz, M.; Strand, L.; Constantinou, M.; Tudose, C.; Kappesser, J.; et al. An international road map to improve pain assessment in people with impaired cognition: The development of the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC) meta-tool. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kunz, M.; de Waal, M.W.M.; Achterberg, W.P.; Gimenez-Llort, L.; Lobbezoo, F.; Sampson, E.L.; van Dalen-Kok, A.H.; Defrin, R.; Invitto, S.; Konstantinovic, L.; et al. The Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition scale (PAIC15): A multidisciplinary and international approach to develop and test a meta-tool for pain assessment in impaired cognition, especially dementia. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohrbach, R.; Bjorner, J.; Jezewski, M.A.; John, M.T.; Lobbezoo, F. Guidelines for Establishing Cultural Equivalency of Instruments; University of Bufalo: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dalen-Kok, A.H.; Achterberg, W.P.; Rijkmans, W.E.; Tukker-van Vuuren, S.A.; Delwel, S.; de Vet, H.C.; Lobbezoo, F.; de Waal, M.W. Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC): Content validity of the Dutch version of a new and universal tool to measure pain in dementia. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fricker, R.D., Jr. Sampling Methods for Web and E-mail Surveys, SAGE Internet Research Methods; Hughes, J., Fielding, N., Lee, R.M., Blank, G., Eds.; Reprinted in The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2012; Chapter 11; pp. 195–216. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10945/38713 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Hernandez-Nieto, R. The coefficient of content validity (Ccv) and the Kappa coefficient (K), to determine content validity according to the technique of experts panel. In Contributions to Statistical Analysis, 1st ed.; BookSurge Publishing: Mérida, Mexico, 2002; p. 228. ISBN 1588987159. [Google Scholar]

- Silveira, M.B.; Saldanha, R.P.; Leite, J.C.C.; Silva, T.O.F.D.; Silva, T.; Filippin, L.I. Construction and validation of content of one instrument to assess falls in the elderly. Einstein 2018, 16, eAO4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Keeney, C.E.; Scharfenberger, J.A.; O’Brien, J.G.; Looney, S.; Pfeifer, M.P.; Hermann, C.P. Initiating and sustaining a standardized pain management program in long-term care facilities. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2008, 9, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovach, C.R.; Logan, B.R.; Noonan, P.E.; Schlidt, A.M.; Smerz, J.; Simpson, M.; Wells, T. Effects of the Serial Trial Intervention on discomfort and behavior of nursing home residents with dementia. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dementiasr 2006, 21, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sirsch, E.; Lukas, A.; Drebenstedt, C.; Gnass, I.; Laekeman, M.; Kopke, K.; Fischer, T.; Guideline workgroup (Schmerzassessment bei älteren Menschen in der vollstationären Altenhilfe, AWMF Registry 145-001). Pain Assessment for Older Persons in Nursing Home Care: An Evidence-Based Practice Guideline. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manietta, C.; Labonté, V.; Thiesemann, R.; Sirsch, E.G.; Möhler, R. Algorithm-based pain management for people with dementia in nursing homes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 4, CD013339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaufmann, L.; Moeller, K.; Marksteiner, J. Pain and Associated Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Patients Suffering from Dementia: Challenges at Different Levels and Proposal of a Conceptual Framework. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 83, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Foraciepe, M.; Silva, A.E.V.F.; Fares, T.G.; Santos, F.C. Pain in older adults with dementia: Brazilian validation of Pain Intensity Measure for Persons with Dementia (PIMD). Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2023 2023, 81, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Haslam-Larmer, L.; Krassikova, A.; Spengler, C.; Wills, A.; Keatings, M.; Babineau, J.; Robert, B.; Heer, C.; McAiney, C.; Bethell, J.; et al. What Do We Know About Nurse Practitioner/Physician Care Models in Long-Term Care: Results of a Scoping Review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2024, 25, 105148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rababa, M.; Tawalbeh, R.; Abu-Zahra, T. Nurses’ perception of uncertainty regarding suspected pain in people with dementia: A qualitative descriptive study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Waal, M.W.M.; van Dalen-Kok, A.H.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Gimenez-Llort, L.; Konstantinovic, L.; de Tommaso, M.; Fischer, T.; Lukas, A.; Kunz, M.; Lautenbacher, S.; et al. Observational pain assessment in older persons with dementia in four countries: Observer agreement of items and factor structure of the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Llort, L.; Bernal, M.L.; Docking, R.; Muntsant-Soria, A.; Torres-Lista, V.; Bulbena, A.; Schofield, P.A. Pain in Older Adults With Dementia: A Survey in Spain. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 592366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lautenbacher, S.; Kunz, M. Facial Pain Expression in Dementia: A Review of the Experimental and Clinical Evidence. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2017, 14, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, P.S.; de Melo, R.C.; de Souza, J.T.; Frost, R.; Gavin, J.P.; Robinson, K.; Boas, P.J.F.V.; Minicucci, M.F.; Aprahamian, I.; Wachholz, P.A.; et al. Frailty identification and management among Brazilian healthcare professionals: A survey. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- In the Chamber of Deputies, CFM Warns About the Need to Train More Geriatricians in the Country|Medical Portal. Available online: https://portal.cfm.org.br/noticias/na-camara-dos-deputados-cfm-defende-formacao-de-mais-geriatras-no-pais (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Shi, T.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhu, L.; Jia, H.; Qian, K.; Shi, S.; Li, X.; Yin, Y.; Ding, Y. Association between pain and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in older adults with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Items in Brazilian Portuguese | Geriatricians (Other Settings) (n = 23) | Geriatricians (LTCF) (n = 23) | Other Health Professionals (n = 19) | Nurses (LTCF) (n = 16) | Physicians (Non-Geriatricians) (n = 12) | Nurses (Hospitals) (n = 7) | Nursing Technicians (LTCF) (n = 2) | Overall Group (n = 102) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FACIAL EXPRESSION | ||||||||

| “Franzindo a testa” (frowning) | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.75 | 0.80 |

| “Apertando os olhos” (narrowing) | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.82 |

| “Levantando o lábio superior” (rising upper lips) | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.71 |

| “Abrindo a boca” (opening the mouth) | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.60 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.62 | 0.65 |

| “Parecendo tenso” (looking tense) | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.83 |

| BODY MOVEMENTS | ||||||||

| “Enrijecido ou rígido” (freezing) | 0.83 | 0.97 | 0.80 | 0.94 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.85 |

| “Postura de proteção” (guarding) | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.93 |

| “Resistindo ao cuidado” (Resisting) | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.87 | 0.83 |

| “Fricção” (Rubbing) | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 0.85 |

| “Inquietação” (Restlessness) | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.78 |

| VOCALIZATION | ||||||||

| “Usando as palavras relacionadas à dor” (Using pain-related words) | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.88 |

| “Gritando” (Shouting) | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.87 | 0.77 |

| “Gemendo” (Groaning) | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.75 | 0.84 |

| “Resmungando” (Mumbling) | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.77 | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.69 |

| “Reclamando” (Complaining) | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.87 | 0.82 |

| Item | Brazilian Nurses LTCF | Brazilian Geriatricians LTCF | Brazilian Geriatricians Non-LTCF | Dutch Nurses LTCF | Dutch Older People’s Care Physicians–LTCF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FACIAL EXPRESSIONS | |||||

| Frowning | x | x | x | x | |

| Narrowing | x | x | x | x | x |

| Raising upper lip | x | x | x | x | x |

| Opening mouth | |||||

| Looking tense facial | x | x | x | ||

| BODY MOVEMENTS | |||||

| Freezing | x | x | x | x | |

| Guarding | x | x | x | x | x |

| Resisting | x | x | |||

| Rubbing | x | x | x | x | x |

| Restlessness | |||||

| VOCALIZATION | |||||

| Using pain-related words | x | x | x | x | x |

| Shouting | x | ||||

| Groaning | x | x | x | x | x |

| Mumbling | |||||

| Complaining | x | x | x | x | x |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azevedo, P.S.; de Souza, J.T.; Jacinto, A.F.; Oliveira, D.; Santos, F.C.d.; Minicucci, M.F.; Villas Boas, P.J.F.; Achterberg, W.; Wachholz, P.A. Reducing Barriers for Best Practice in People Living with Dementia: Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Content Validity of the Brazilian Version of the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC-15) Meta-Tool. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091324

Azevedo PS, de Souza JT, Jacinto AF, Oliveira D, Santos FCd, Minicucci MF, Villas Boas PJF, Achterberg W, Wachholz PA. Reducing Barriers for Best Practice in People Living with Dementia: Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Content Validity of the Brazilian Version of the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC-15) Meta-Tool. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091324

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzevedo, Paula Schmidt, Juli Thomaz de Souza, Alessandro Ferrari Jacinto, Déborah Oliveira, Fania Cristina dos Santos, Marcos Ferreira Minicucci, Paulo José Fortes Villas Boas, Wilco Achterberg, and Patrick Alexander Wachholz. 2025. "Reducing Barriers for Best Practice in People Living with Dementia: Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Content Validity of the Brazilian Version of the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC-15) Meta-Tool" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091324

APA StyleAzevedo, P. S., de Souza, J. T., Jacinto, A. F., Oliveira, D., Santos, F. C. d., Minicucci, M. F., Villas Boas, P. J. F., Achterberg, W., & Wachholz, P. A. (2025). Reducing Barriers for Best Practice in People Living with Dementia: Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Content Validity of the Brazilian Version of the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC-15) Meta-Tool. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091324