Everyday Discrimination in Young Adulthood and Depressive Symptoms at Early Midlife: The Moderating Role of Parent–Child Relationships

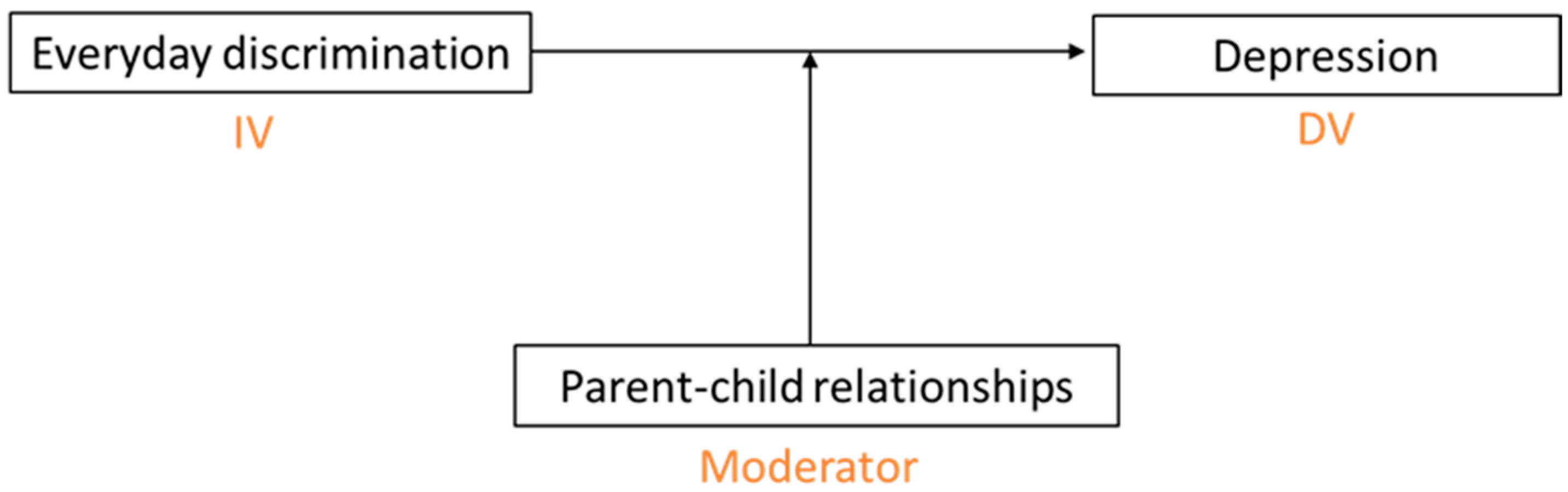

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Life Course, Discrimination, and Depressive Symptoms

1.2. Moderator Role of Parent–Child Relationships

1.3. Purpose of the Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Depressive Symptoms

2.2.2. Everyday Discrimination

2.2.3. Parent–Child Relationships

2.2.4. Covariates

2.3. Analytic Sample

2.4. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Everyday Discrimination and Depression

3.2. Parent–Child Relationships as a Moderator

3.2.1. Parental Closeness

3.2.2. Satisfaction with Communication with Parents

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krieger, N. Embodying inequality: A review of concepts, measures, and methods for studying health consequences of discrimination. Int. J. Health Serv. 1999, 29, 295–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.J.; Avison, W.R. Status variations in stress exposure: Implications for the interpretation of research on race, socioeconomic status, and gender. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2003, 44, 488–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.J.; Lloyd, D.A. Stress burden and the lifetime incidence of psychiatric disorder in young adults: Racial and ethnic contrasts. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2004, 61, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudson, D.L.; Neighbors, H.W.; Geronimus, A.T.; Jackson, J.S. Racial Discrimination, John Henryism, and Depression Among African Americans. J. Black Psychol. 2015, 42, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouzon, D.M.; Taylor, R.J.; Keith, V.M.; Nicklett, E.J.; Chatters, L.M. Discrimination and psychiatric disorders among older African Americans. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2016, 32, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, E.A.; Smart Richman, L. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Neighbors, H.W.; Jackson, J.S. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, G.H.; Chen, Y.; Murry, V.M.; Ge, X.; Simons, R.L.; Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; Cutrona, C.E. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child. Dev. 2006, 77, 1170–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, F.X.; Gerrard, M.; Cleveland, M.J.; Wills, T.A.; Brody, G. Perceived discrimination and substance use in African american parents and their children: A panel study. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, D.L.; Bullard, K.M.; Neighbors, H.W.; Geronimus, A.T.; Yang, J.; Jackson, J.S. Are benefits conferred with greater socioeconomic position undermined by racial discrimination among African American men? J. Men’s Health 2012, 9, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Mickelson, K.D.; Williams, D.R. the prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1999, 40, 208–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBOIS, W.E.B. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study; Schocken Books: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, D.R.; Sternthal, M. Understanding racial-ethnic disparities in health: Sociological contributions. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, S15–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.H.; Hargrove, T.W.; Homan, P.; Adkins, D.E. Racialized Health Inequities: Quantifying Socioeconomic and Stress Pathways Using Moderated Mediation. Demography 2023, 60, 675–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G. Is Racism a Fundamental Cause of Inequalities in Health? Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Yan, Y.; Jackson, J.S.; Anderson, N.B. Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health: Socio-economic Status, Stress and Discrimination. J. Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essed, P. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory, vol. 2; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Harnois, C.E. What do we measure when we measure perceptions of everyday discrimination? Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.T.; Cogburn, C.D.; Williams, D.R. Self-Reported experiences of discrimination and health: Scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 11, 407–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, G.C.; Spencer, M.S.; Chen, J.; Takeuchi, D. A Nationwide Study of Discrimination and Chronic Health Conditions Among Asian Americans. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 1275–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavalko, E.K.; Mossakowski, K.N.; Hamilton, V.J. Does perceived discrimination affect health? Longitudinal relationships between work discrimination and women’s physical and emotional health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2003, 44, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, N.; Smith, K.; Naishadham, D.; Hartman, C.; Barbeau, E.M. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 1576–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, T.R.; Kamarck, T.W.; Shiffman, S. Validation of the Detroit Area Study Discrimination Scale in a community sample of older African American adults: The Pittsburgh healthy heart project. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2004, 11, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, K.H.; Kohn-Wood, L.P.; Spencer, M. An examination of the african american experience of everyday discrimination and symptoms of psychological distress. Community Ment. Health J. 2006, 42, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brondolo, E.; Gallo, L.C.; Myers, H.F. Race, racism and health: Disparities, mechanisms, and interventions. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.-L. Perceived discrimination and depression among new migrants to Hong Kong: The moderating role of social support and neighborhood collective efficacy. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 138, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xu, J.; Granberg, E.; Wentworth, W.M. A Longitudinal Study of Social Status, Perceived Discrimination, and Physical and Emotional Health Among Older Adults. Res. Aging 2012, 34, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, D.; Lambert, S.F.; Ialongo, N.S. Longitudinal associations between experienced racial discrimination and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 1190–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, A.J.; Gravlee, C.C.; Williams, D.R.; Israel, B.A.; Mentz, G.; Rowe, Z. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among african american women in detroit: Results from a longitudinal analysis. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, D.L.; Hayward, M.D.; Crimmins, E.M. Does childhood health affect chronic morbidity in later life? Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, K.F.; Farmer, M.M. Utility of Health data from Social Surveys: Is There a Gold Standard for Measuring Morbidity? Am. Sociol. Rev. 1999, 64, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.R.; Hauser, R.M.; Sheridan, J.T. Occupational Stratification across the Life Course: Evidence from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2002, 67, 432–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Rand, A.M. The Precious and the Precocious: Understanding Cumulative Disadvantage and Cumulative Advantage Over the Life Course. Gerontologist 1996, 36, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.E.; Wu, C.-L. Education, age, and the cumulative advantage in health. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1996, 37, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannefer, D. Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2003, 58, S327–S337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuey, K.M.; Willson, A.E. Cumulative Disadvantage and Black-White Disparities in Life-Course Health Trajectories. Res. Aging 2008, 30, 200–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: An ecosocial approach. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, S.L. Conceptualizing and Identifying Cumulative Adversity and Protective Resources: Implications for Understanding Health Inequalities. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2005, 60, S130–S134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banaji, M.R.; Fiske, S.T.; Massey, D.S. Systemic racism: Individuals and interactions, institutions and society. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2021, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earnshaw, V.; Rosenthal, L.; Carroll-Scott, A.; Santilli, A.; Gilstad-Hayden, K.; Ickovics, J.R. Everyday discrimination and physical health: Exploring mental health processes. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 2218–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas, A.G.; Ong, A.D.; Carvalho, K.; Ho, T.; Chan, S.W.; Allen, J.D.; Chen, R.; Rodgers, J.; Biba, U.; Williams, D.R. Discrimination and systemic inflammation: A critical review and synthesis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, L.; Liu, S.; Heim, C.; Heinz, A. The effects of social isolation stress and discrimination on mental health. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, G.; De La Cruz, N.L.; Gould, L.H.; Liu, S.Y.; Seligson, A.L. Association between racial discrimination and health-related quality of life and the impact of social relationships. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 2793–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Layton, J.B.; Brayne, C. Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLOS Med. 2010, 7, e1000316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawachi, I. Social ties and mental health. J. Hered. 2001, 78, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtorta, N.K.; Kanaan, M.; Gilbody, S.; Ronzi, S.; Hanratty, B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart 2016, 102, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, D.; Adynski, H.; Harris, R.; Zou, B.; Taylor, J.Y.; Santos, H.P. Social Support Is Protective Against the Effects of Discrimination on Parental Mental Health Outcomes. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2024, 30, 953–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.D.; Harris, S.K.; Woods, E.R.; Buman, M.P.; Cox, J.E. Longitudinal study of depressive symptoms and social support in adolescent mothers. Matern. Child. Health J. 2011, 16, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatters, L.M.; Taylor, R.J.; Woodward, A.T.; Nicklett, E.J. Social support from church and family members and depressive symptoms among older african americans. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatters, L.M.; Nguyen, A.W.; Taylor, R.J.; Hope, M.O. church and family support networks and depressive symptoms among african americans: Findings from the national survey of american life. J. Community Psychol. 2018, 46, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.W.; Walton, Q.L.; Thomas, C.; Mouzon, D.M.; Taylor, H.O. Social support from friends and depression among African Americans: The moderating influence of education. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, D.H.; Lee, S.; Lincoln, K.D.; Ihara, E.S. Discrimination, family relationships, and major depression among Asian Americans. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2012, 14, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Thomas, P.; Liu, H.; Umberson, D. Family Relationships and Well-Being. Innov. Aging 2017, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, K.D.; Chae, D.H. Emotional support, negative interaction and major depressive disorder among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Chest 2012, 47, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.J.M.; Chae, D.H.; Lincoln, K.D.M.; Chatters, L.M. Extended Family and Friendship Support Networks Are Both Protective and Risk Factors for Major Depressive Disorder and Depressive Symptoms Among African-Americans and Black Caribbeans. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2015, 203, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.W.; Chatters, L.M.; Taylor, R.J.; Mouzon, D.M. Social Support from Family and Friends and Subjective Well-Being of Older African Americans. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 17, 959–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buka, S.S.L.; Beers, L.S.; Biel, M.M.G.; Counts, N.Z.; Hudziak, J.; Parade, S.H.; Paris, R.; Seifer, R.; Drury, S.S. The Family is the Patient: Promoting Early Childhood Mental Health in Pediatric Care. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021053509L. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, A.; Broadbent, A.; Brooks, E.; Bulsara, K.; Donoghue, K.; Saijaf, R.; Sampson, K.N.; Thomson, A.; Fearon, P.; Lawrence, P.J. The impact of family interventions on communication in the context of anxiety and depression in those aged 14–24 years: Systematic review of randomised control trials. BJPsych Open 2023, 9, e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, M. Separation: Anxiety and Anger: Attachment and Loss: Volume 1. Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Grotevant, H.D.; Cooper, C.R. Individuation in Family Relationships: A Perspective on Individual Differences in the Development of Identity and Role-Taking Skill in Adolescence. Hum. Dev. 1986, 29, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumrind, D.; Black, A.E. Socialization practices associated with dimensions of competence in preschool boys and girls. Child. Dev. 1967, 38, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med. 1976, 38, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windle, M. Temperament and social support in adolescence: Interrelations with depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors. J. Youth Adolesc. 1992, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X. Mother–Child Relationships and Depressive Symptoms in the Transition to Adulthood: An Examination of Ra-cial and Ethnic Differences’. In Transitions into Parenthood: Examining the Complexities of Childrearing; Blair, S.L., Costa, R.P., Eds.; in Contemporary Perspectives in Family Research; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2019; Volume 15, pp. 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Grant, A. Parent-Child Relationships and Mental Health in the Transition to Adulthood by Race and Ethnicity. Curr. J. Divers. Scholarsh. Soc. Change 2022, 2, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.P.; Insabella, G.; Porter, M.R.; Smith, F.D.; Land, D.; Phillips, N. A social-interactional model of the development of depressive symptoms in adolescence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 74, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, S.O.; Brown, J.S.; Elder, G.H. Depressive Symptoms, Stress, and Support: Gendered Trajectories From Adolescence to Young Adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2006, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Antich, J.; Lukens, E.; Davies, M.; Goetz, D.; Brennan-Quattrock, J.; Todak, G. Psychosocial functioning in prepubertal major depressive disorders. II. Interpersonal relationships after sustained recovery from affective episode. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1985, 42, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilino, W.S. From Adolescent to Young Adult: A Prospective Study of Parent-Child Relations during the Transition to Adulthood. J. Marriage Fam. 1997, 59, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Grant, A. Parent–Child Relationships from Adolescence to Adulthood: An Examination of Children’s and Parent’s Reports of Intergenerational Solidarity by Race, Ethnicity, Gender, and Socioeconomic Status from 1994–2018 in the United States. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.S.; Rossi, P.H. Of Human Bonding: Parent-Child Relations Across the Life Course; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, A.; Orbuch, T.L.; Axinn, W.G. Parent-Child Relationships During the Transition to Adulthood. J. Fam. Issues 1995, 16, 538–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillemer, K.A.; Mccartney, K. Parent-Child Relations Throughout Life; L. Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, K.M.; Halpern, C.T.; AWhitsel, E.; Hussey, J.M.; AKilleya-Jones, L.; Tabor, J.; Dean, S.C. Cohort Profile: The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 1415–1415k. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.M. The Add Health Study: Design and Accomplishments. 2013. Available online: https://addhealth.cpc.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/docs/user_guides/DesignPaperWave_I-IV.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Benner, A.D.; Chen, S.; Fernandez, C.C.; Hayward, M.D. The Potential for Using a Shortened Version of the Everyday Discrimination Scale in Population Research with Young Adults: A Construct Validation Investigation. Sociol. Methods Res. 2024, 53, 804–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J.; Zhang, X.; Kim, I. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Intergenerational Relationships in Young Adulthood: Variation Across Gender, Race and Ethnicity. J. Interpers. Violence 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Harris, K.M. ‘Guidelines for Analyzing Add Health Data’, Carolina Digital Repository. 2020. Available online: https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/articles/k0698990v?locale=en (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Kaiser, C.R.; Major, B. A Social Psychological Perspective on Perceiving and Reporting Discrimination. Law Soc. Inq. 2006, 31, 801–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L.I. The sociological study of stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1989, 30, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.L.; Narcisse, M.-R. Discrimination, Depression, and Anxiety Among US Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e252404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, E.R.; Omari, S.R. Race, Class and the Dilemmas of Upward Mobility for African Americans. J. Soc. Issues 2003, 59, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.K.; Lavner, J.A.; Carter, S.E.; Hart, A.R.; Beach, S.R.H. Protective parenting behavior buffers the impact of racial discrimination on depression among Black youth. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, S.M.; Kwon, E.; Brody, G.H.; Azarmehr, R.; Reck, A.J.; Anderson, T.; Sperr, M. Family-Centered Prevention to Reduce Discrimination-Related Depressive Symptoms Among Black Adolescents: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 2023, 6, e2340567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frosch, C.A.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; O’bAnion, D.D. Parenting and Child Development: A Relational Health Perspective. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2021, 15, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuang, M.; Yiqing, W.; Ling, J.; Guanzhen, O.; Jing, G.; Zhiyong, Q.; Xiaohua, W. Relationship between parent–child attachment and depression among migrant children and left-behind children in China. Public Health 2022, 204, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Variables | Data Source (Wave from Add Health) |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Depression (CES-D-5) | Wave V |

| Independent variable | Everyday discrimination (EDS) | Wave IV |

| Moderator | Parent-child relationships | Wave IV |

| Covariates | Race/ethnicity | Wave I |

| Age | Wave IV | |

| Gender | Wave I | |

| Immigrant generation status | Wave I | |

| Marital status | Wave IV | |

| Employment status | Wave IV | |

| Household income level | Wave IV | |

| Highest educational attainment | Wave IV | |

| Family structure (living with parents or not) | Wave I | |

| Depression (CES-D-5) | Wave I |

| Variable | Mother Sample (N = 9390) | Father Sample (N = 8229) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Female | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Age at Wave IV, mean (SD) | 28.88 (0.11) | 28.86 (0.12) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.70 | 0.73 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| Hispanic | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Immigrant generation status | ||

| Born in the U.S. | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Foreign born | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 0.47 | 0.46 |

| Married | 0.53 | 0.54 |

| Employment status | ||

| Not employed for at least 10 h/week | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| Employed for at least 10 h/week | 0.66 | 0.66 |

| Household income level | ||

| USD 24,999 and less | 0.16 | 0.15 |

| USD 25,000–49,000 | 0.29 | 0.28 |

| USD 50,000 or above | 0.55 | 0.57 |

| Highest educational attainment | ||

| High school or less | 0.22 | 0.22 |

| Some college or vocational | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| Completed college or above | 0.34 | 0.36 |

| Family structure | ||

| Two biological parents | 0.58 | 0.63 |

| Two parents | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| Single parent | 0.21 | 0.16 |

| Other | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Depression (CES-D) at Wave I, mean (SD) | 0.48 (0.01) | 0.47 (0.01) |

| Reason for everyday discrimination | (n = 2110) | (n = 1799) |

| Ancestry or national origin | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Gender | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Race | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| Age | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| Religion | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Height/weight | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Skin color | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Sexual orientation | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Education/income | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| A physical disability | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Other | 0.59 | 0.59 |

| Variable | Mother Sample | Father Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Everyday discrimination | 0.13 *** | 0.01 | 0.13 *** | 0.01 |

| Regression including covariates | 0.10 *** | 0.01 | 0.10 *** | 0.01 |

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Hispanic | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | −0.07 * | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.04 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Family structure | ||||

| Two parents | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Single parent | 0.04 * | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Other | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Immigrant generation status | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Marital status | −0.06 *** | 0.01 | −0.06 *** | 0.02 |

| Employment status | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| Household income level | ||||

| USD 25,000–49,000 | −0.05 * | 0.02 | −0.09 ** | 0.03 |

| USD 50,000 or above | −0.09 *** | 0.02 | −0.13 *** | 0.03 |

| Highest educational attainment | ||||

| Some college or vocational | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Completed college or above | −0.10 *** | 0.02 | −0.09 *** | 0.02 |

| Depression (CES-D) at Wave I | 0.16 *** | 0.02 | 0.16 *** | 0.02 |

| Variable | Mother Sample | Father Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Everyday discrimination | 0.16 ** | 0.06 | 0.13 * | 0.05 |

| Maternal closeness | −0.04 * | 0.01 | - | - |

| Everyday discrimination x maternal closeness | −0.01 | 0.01 | - | - |

| Paternal closeness | - | - | −0.03 * | 0.01 |

| Everyday discrimination x paternal closeness | - | - | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Hispanic | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | −0.08 * | 0.03 | −0.08 * | 0.04 |

| Age | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Family structure | ||||

| Two parents | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Single parent | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Other | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Immigrant generation status | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Marital status | −0.06 *** | 0.01 | −0.05 *** | 0.02 |

| Employment status | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 |

| Household income level | ||||

| USD 25,000–49,000 | −0.05 * | 0.02 | −0.08 ** | 0.03 |

| USD 50,000 or above | −0.09 *** | 0.02 | −0.13 *** | 0.02 |

| Highest educational attainment | ||||

| Some college or vocational | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Completed college or above | −0.10 *** | 0.02 | −0.08 *** | 0.02 |

| Depression (CES-D) at Wave I | 0.16 *** | 0.02 | 0.16 *** | 0.02 |

| Variable | Mother Sample | Father Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Everyday discrimination | 0.13 * | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Satisfaction with communication with mother | −0.03 * | 0.01 | - | - |

| Everyday discrimination x satisfaction with communication with mother | −0.01 | 0.01 | - | - |

| Satisfaction with communication with father | - | - | −0.03 * | 0.01 |

| Everyday discrimination x satisfaction with communication with father | - | - | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | −0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Hispanic | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | −0.07 * | 0.03 | −0.07 * | 0.03 |

| Age | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Family structure | ||||

| Two parents | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.02 |

| Single parent | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Other | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Immigrant generation status | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Marital status | −0.06 *** | 0.02 | −0.06 *** | 0.02 |

| Employment status | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Household income level | ||||

| USD 25,000–49,000 | −0.05 * | 0.03 | −0.09 ** | 0.03 |

| USD 50,000 or above | −0.09 *** | 0.02 | −0.13 *** | 0.02 |

| Highest educational attainment | ||||

| Some college or vocational | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Completed college or above | −0.10 *** | 0.02 | −0.09 *** | 0.02 |

| Depression (CES-D) at Wave I | 0.16 *** | 0.02 | 0.16 *** | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herath, B.; Zhang, X. Everyday Discrimination in Young Adulthood and Depressive Symptoms at Early Midlife: The Moderating Role of Parent–Child Relationships. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091323

Herath B, Zhang X. Everyday Discrimination in Young Adulthood and Depressive Symptoms at Early Midlife: The Moderating Role of Parent–Child Relationships. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(9):1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091323

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerath, Binoli, and Xing Zhang. 2025. "Everyday Discrimination in Young Adulthood and Depressive Symptoms at Early Midlife: The Moderating Role of Parent–Child Relationships" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 9: 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091323

APA StyleHerath, B., & Zhang, X. (2025). Everyday Discrimination in Young Adulthood and Depressive Symptoms at Early Midlife: The Moderating Role of Parent–Child Relationships. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(9), 1323. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22091323