PeerOnCall: Evaluating Implementation of App-Based Peer Support in Canadian Public Safety Organizations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analyses

3. Results

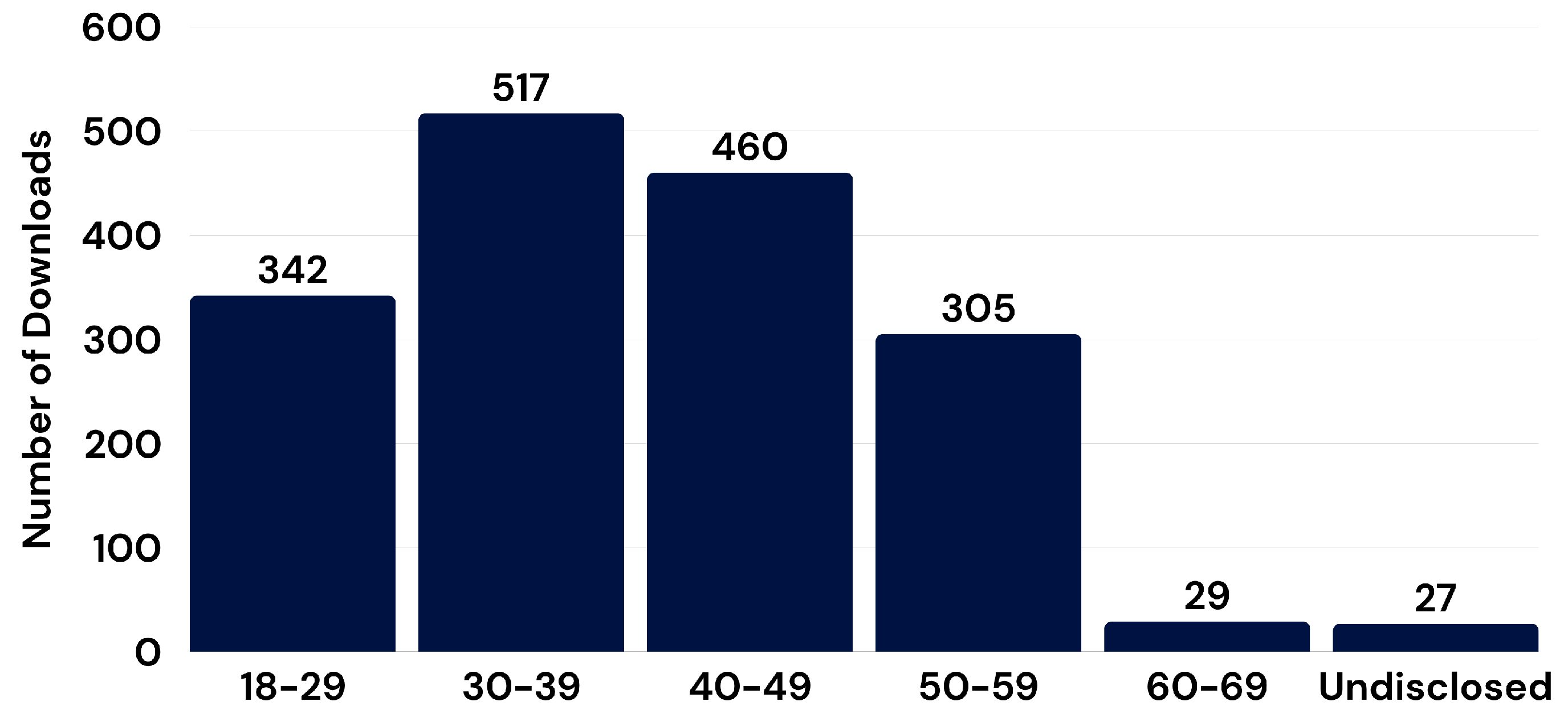

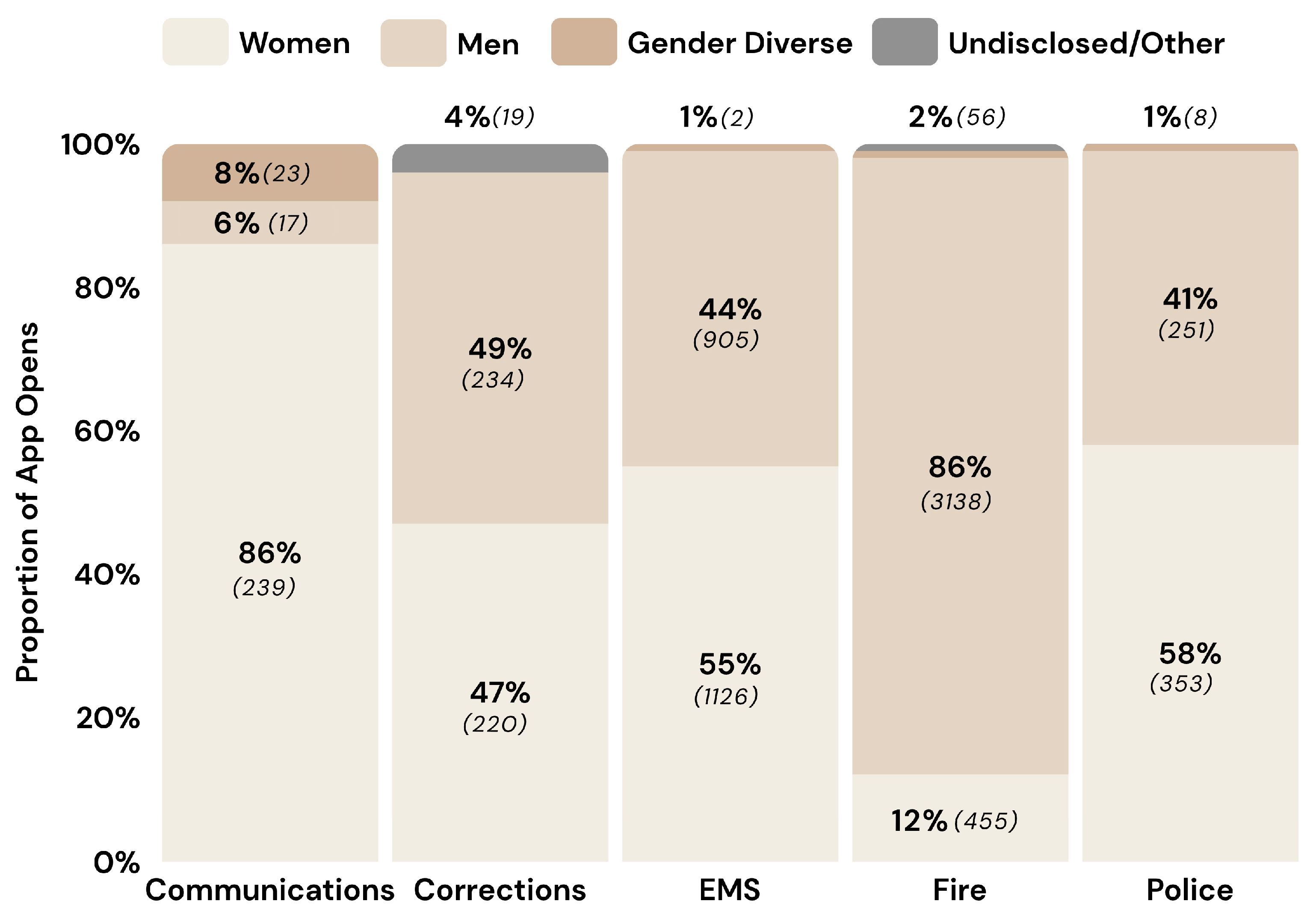

3.1. Characteristics of App Users

3.2. App Use Trends

3.3. Qualitative Analyses

3.3.1. Implementation Processes

3.3.2. Facilitators of App Use

3.3.3. Barriers to App Use

“Some people won’t seek help, regardless of the resource or format. There’s also a culture of the strong man, the superhero who doesn’t need anyone and is supposed to provide help rather than seek it. They’re often accustomed to offering help rather than seeking it. So, this change in role is difficult.”

“I think the biggest concern is convincing people this app isn’t something that’s being monitored by our department. There’s this underlying fear that maybe it’s tracking who’s using it or what’s being said. It’s not like a red flag is going to pop up on the inspector’s screen when someone talks to a peer supporter, but that’s what people worry about. They don’t want their struggles to be known by management, even though we’ve tried to assure them that the app is completely private. This fear has definitely kept some people from even downloading it.”

“There’s a real cultural hurdle we’re facing with this app. People are used to doing things a certain way, and introducing something new, especially something digital, is met with skepticism. …. But when there’s this underlying mistrust or lack of understanding, it’s hard to get people on board with any new technology, no matter how good it is.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Patterns of App Use

4.2. Facilitators and Barriers to App Use

4.3. Recommendations for Implementation

4.4. Study Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSP | Public Safety Personnel |

| TAL | Technology Adoption Lifecyle |

| CFIR | Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research |

| mHealth | Mobile health |

References

- Heber, A.; Testa, V.; Groll, D.; Ritchie, K.; Tam-Seto, L.; Mulligan, A.; Sullo, E.; Schick, A.; Bose, E.; Jabbari, Y.; et al. Glossary of terms: A shared understanding of the common terms used to describe psychological trauma, version 3.0. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2023, 43, S1–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, R.C. Healthy Minds, Safe Communities: Supporting our Public Safety Officers Through a National Strategy for Operational Stress Injuries. Report of the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security; Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016; Available online: https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/421/SECU/Reports/RP8457704/securp05/securp05-e.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Turner, S.; Taillieu, T.; Duranceau, S.; LeBouthillier, D.M.; Sareen, J.; Ricciardelli, R.; Macphee, R.S.; Groll, D.; et al. Mental disorder symptoms among public safety personnel in Canada. Can. J. Psychiatry 2018, 63, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Taillieu, T.; Turner, S.; Mason, J.E.; Ricciardelli, R.; McCreary, D.R.; Vaughan, A.D.; Anderson, G.S.; Krakauer, R.L.; et al. Assessing the relative impact of diverse stressors among public safety personnel. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, E1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, R.; Carleton, R.N.; Groll, D.; Cramm, H. Qualitatively unpacking Canadian public safety personnel experiences of trauma and their well-being. Can. J. Criminol. Crim. Justice 2018, 60, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogan, N.; Craig, A.; Milligan, L.; McCluskey, R.; Burns, T.; Ptak, W.; Kirk, A.; Graf, C.; Goodman, J.; De Kock, J. ‘I’ve got no PPE to protect my mind’: Understanding the needs and experiences of first responders exposed to trauma in the workplace. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2024, 15, 2395113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auth, N.M.; Booker, M.J.; Wild, J.; Riley, R. Mental health and help seeking among trauma-exposed emergency service staff: A qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e047814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.; Agud, K.; McSweeney, J. Barriers and facilitators to seeking mental health care among first responders: “Removing the Darkness. ” J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2020, 26, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haugen, P.T.; McCrillis, A.M.; Smid, G.E.; Nijdam, M.J. Mental health stigma and barriers to mental health care for first responders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 94, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaveladze, B.T.; Wasil, A.R.; Bunyi, J.B.; Ramirez, V.; Schueller, S.M. User experience, engagement, and popularity in mental health apps: Secondary analysis of app analytics and expert app reviews. JMIR Hum. Factors 2022, 9, e30766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecomte, T.; Potvin, S.; Corbière, M.; Guay, S.; Samson, C.; Cloutier, B.; Francoeur, A.; Pennou, A.; Khazaal, Y. Mobile apps for mental health issues: Meta-review of meta-analyses. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e17458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Paras, C.; Sasangohar, F. PTSD coach usability testing: A mobile health app for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Proc. Int. Symp. Hum. Factors Ergon. Health Care 2017, 6, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voth, M.; Chisholm, S.; Sollid, H.; Jones, C.; Smith-MacDonald, L.; Brémault-Phillips, S. Efficacy, effectiveness, and quality of resilience-building mobile health apps for military, veteran, and public safety personnel populations: Scoping literature review and app evaluation. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e26453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, A.; Quesada, J.; Silva, J.; Judycki, S.; Mills, P.R. The impact of digital health interventions on health-related outcomes in the workplace: A systematic review. Digit. Health 2018, 4, 2055207618770861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, E.A.; Gordeev, V.S.; Schreyögg, J. Effectiveness of occupational e-mental health interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2019, 45, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, E.; Jones, N.; Peters, S.E.; Torous, J.; Glozier, N. Digital mHealth interventions for employees: Systematic review and meta-analysis of their effects on workplace outcomes. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, e518–e525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, S.; Harris, P.R.; Cavanagh, K. Improving employee well-being and effectiveness: Systematic review and meta-analysis of web-based psychological interventions delivered in the workplace. J. Med Internet Res. 2017, 19, e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghouts, J.; Eikey, E.; Mark, G.; De Leon, C.; Schueller, S.M.; Schneider, M.; Stadnick, N.; Zheng, K.; Mukamel, D.; Sorkin, D.H. Barriers to and facilitators of user engagement with digital mental health interventions: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, E.M.; Raiker, J.S. Engagement and retention in digital mental health interventions: A narrative review. BMC Digit. Health 2024, 2, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wherton, J.; Papoutsi, C.; Lynch, J.; Hughes, G.; A’Court, C.; Hinder, S.; Fahy, N.; Procter, R.; Shaw, S. Beyond adoption: A new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, R.M.; Toppo, C.; Raggi, A.; de Mul, M.; de Miquel, C.; Pugliese, M.T.; van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M.; Ortiz-Tallo, A.; Salvador-Carulla, L.; Lukersmith, S.; et al. Strategies for implementing occupational eMental health interventions: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e34479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggi, A.; Bernard, R.M.; Toppo, C.; Sabariego, C.; Salvador Carulla, L.; Lukersmith, S.; Roijen, L.H.-V.; Merecz-Kot, D.; Olaya, B.; Lima, R.A.; et al. The EMPOWER occupational e–mental health intervention implementation checklist to foster e–mental health interventions in the workplace: Development study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e48504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, S.; Carleton, R.N.; Czarnuch, S.; MacDermid, J.; MacPhee, R.; Ricciardelli, R.; Sinden, K. PeerOnCall: App-based peer support for Canadian public safety personnel. Justice Rep. 2023, 38, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Curran, G.M.; Bauer, M.; Mittman, B.; Pyne, J.M.; Stetler, C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012, 50, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Reardon, C.M.; Widerquist, M.A.O.; Lowery, J. The updated Consolidated Framework for implementation research based on user feedback. Implement. Sci. 2022, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.K.; Shoup, J.A.; Raebel, M.A.; Anderson, C.B.; Wagner, N.M.; Ritzwoller, D.P.; Bender, B.G. Planning for implementation success using RE-AIM and CFIR frameworks: A qualitative study. Front. Public Health. 2020, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. A review of technology acceptance and adoption models and theories. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 22, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G. Marketing and selling disruptive products to mainstream customers. In Crossing the Chasm, 3rd ed.; HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baumel, A.; Muench, F.; Edan, S.; Kane, J.M. Objective User engagement with mental health apps: Systematic search and panel-based usage analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e14567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh, T. How to improve success of technology projects in health and social care. Public Health Res. Pract. 2018, 28, e2831815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, J.; O’Donnell, S.; Roche, E.; White, P.J.; Carroll, P.; Richardson, N. Mental health stigma reduction interventions among men: A systematic review. Am. J. Men’s. Health 2024, 18, 15579883241299353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goraya, N.K.; Alvarez, E.; Young, M.; Moll, S. PeerOnCall: Exploring how organizational culture shapes implementation of a peer support app for public safety personnel. Compr. Psychiatry 2024, 135, 152524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, B.J.; Waltz, T.J.; Chinman, M.J.; Damschroder, L.J.; Smith, J.L.; Matthieu, M.M.; Proctor, E.K.; E Kirchner, J. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PSP Sector | Orgs (#) | Employees (#) | Downloads (#; %) | # of Times App Opened | Average # App Opens Per User |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Safety Communications | 2 | 118 | 54 (45.8) | 279 | 5.16 |

| Corrections | 14 | 1117 | 131 (11.7) | 473 | 3.61 |

| Fire | 14 | 4629 | 841 (18.2) | 3649 | 4.34 |

| Paramedic | 10 | 2092 | 436 (20.8) | 2039 | 4.67 |

| Police | 2 | 3320 | 271 (8.2) | 612 | 2.26 |

| Total | 42 | 11,401 | 1759 (15.4) | 7052 | 4.01 |

| Sector | # Orgs | # Champions | # Baseline Interviews | # Follow-up Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communications | 2 | 7 | 7 | 6 (3 mo) 4 (6 mo) |

| Corrections | 14 | 12 | 12 | 7 (3 mo) 7 (6 mo) |

| EMS | 10 | 24 | 14 | 3 (6 mo) |

| Fire | 14 | 21 | 21 | 12 (3 mo) 11(6 mo) |

| Police | 2 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 42 | 55 | 57 | 50 |

| Barrier | Implementation Strategy |

|---|---|

| Communication channels |

|

| Culture of stoicism |

|

| Stigma and confidentiality concerns |

|

| Unable to use phone at work |

|

| Mistrust, resistance to change |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moll, S.E.; Ricciardelli, R.; Carleton, R.N.; MacDermid, J.C.; Czarnuch, S.; MacPhee, R.S. PeerOnCall: Evaluating Implementation of App-Based Peer Support in Canadian Public Safety Organizations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081269

Moll SE, Ricciardelli R, Carleton RN, MacDermid JC, Czarnuch S, MacPhee RS. PeerOnCall: Evaluating Implementation of App-Based Peer Support in Canadian Public Safety Organizations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081269

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoll, Sandra E., Rosemary Ricciardelli, R. Nicholas Carleton, Joy C. MacDermid, Stephen Czarnuch, and Renée S. MacPhee. 2025. "PeerOnCall: Evaluating Implementation of App-Based Peer Support in Canadian Public Safety Organizations" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081269

APA StyleMoll, S. E., Ricciardelli, R., Carleton, R. N., MacDermid, J. C., Czarnuch, S., & MacPhee, R. S. (2025). PeerOnCall: Evaluating Implementation of App-Based Peer Support in Canadian Public Safety Organizations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081269