The Effects of the Red River Jig on the Wholistic Health of Adults in Saskatchewan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context, Community Partner, and Ethics

2.2. Intervention and Participants

2.3. Study Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

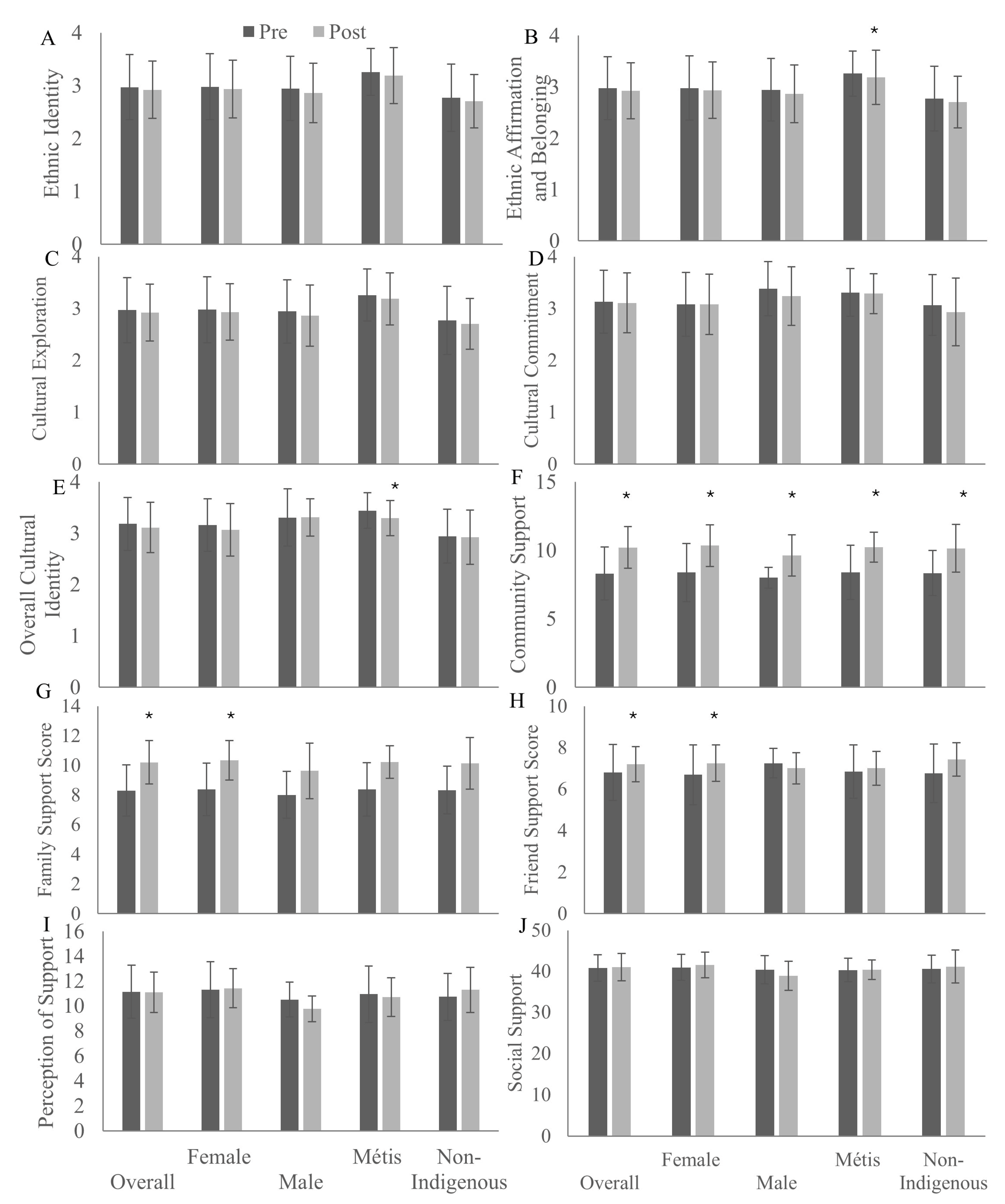

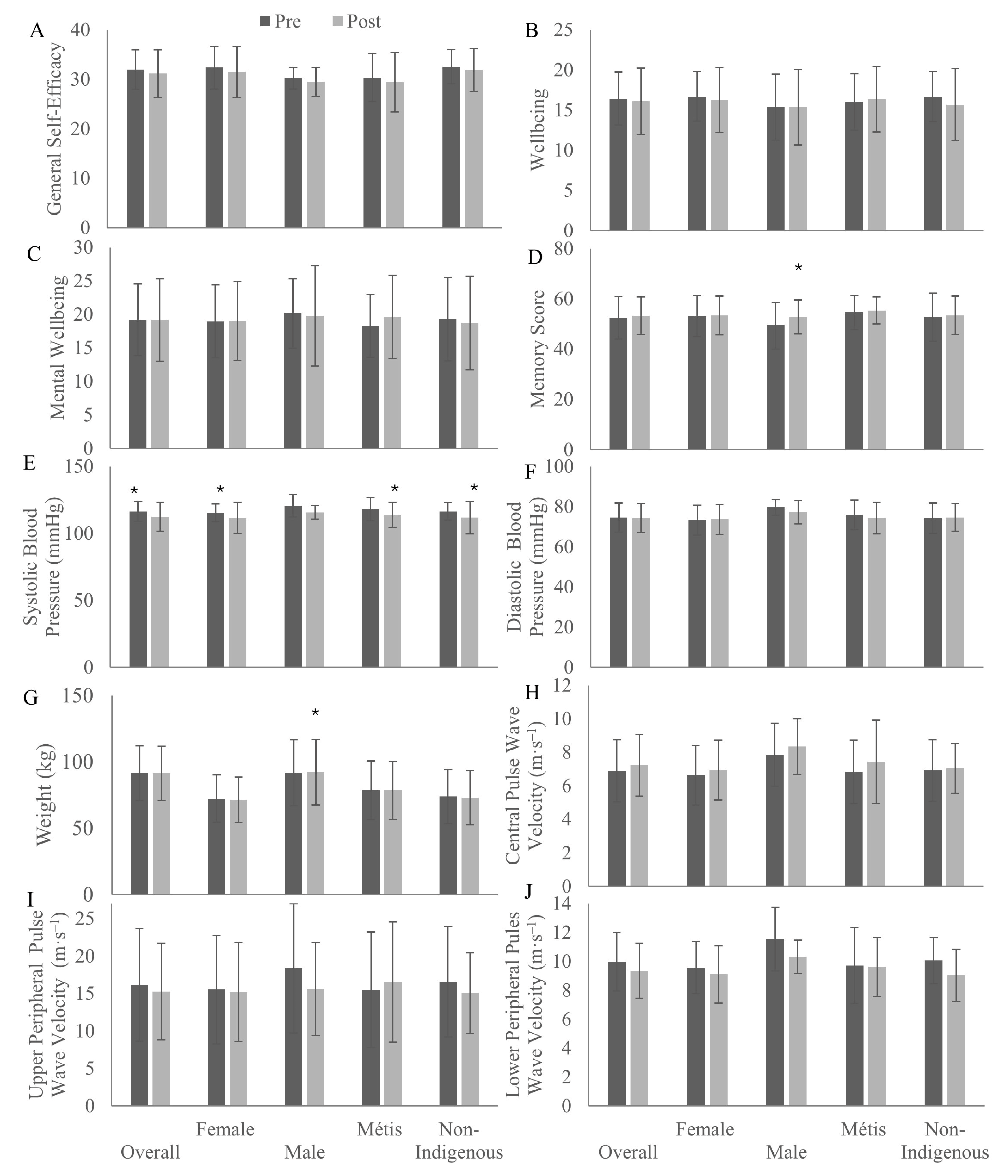

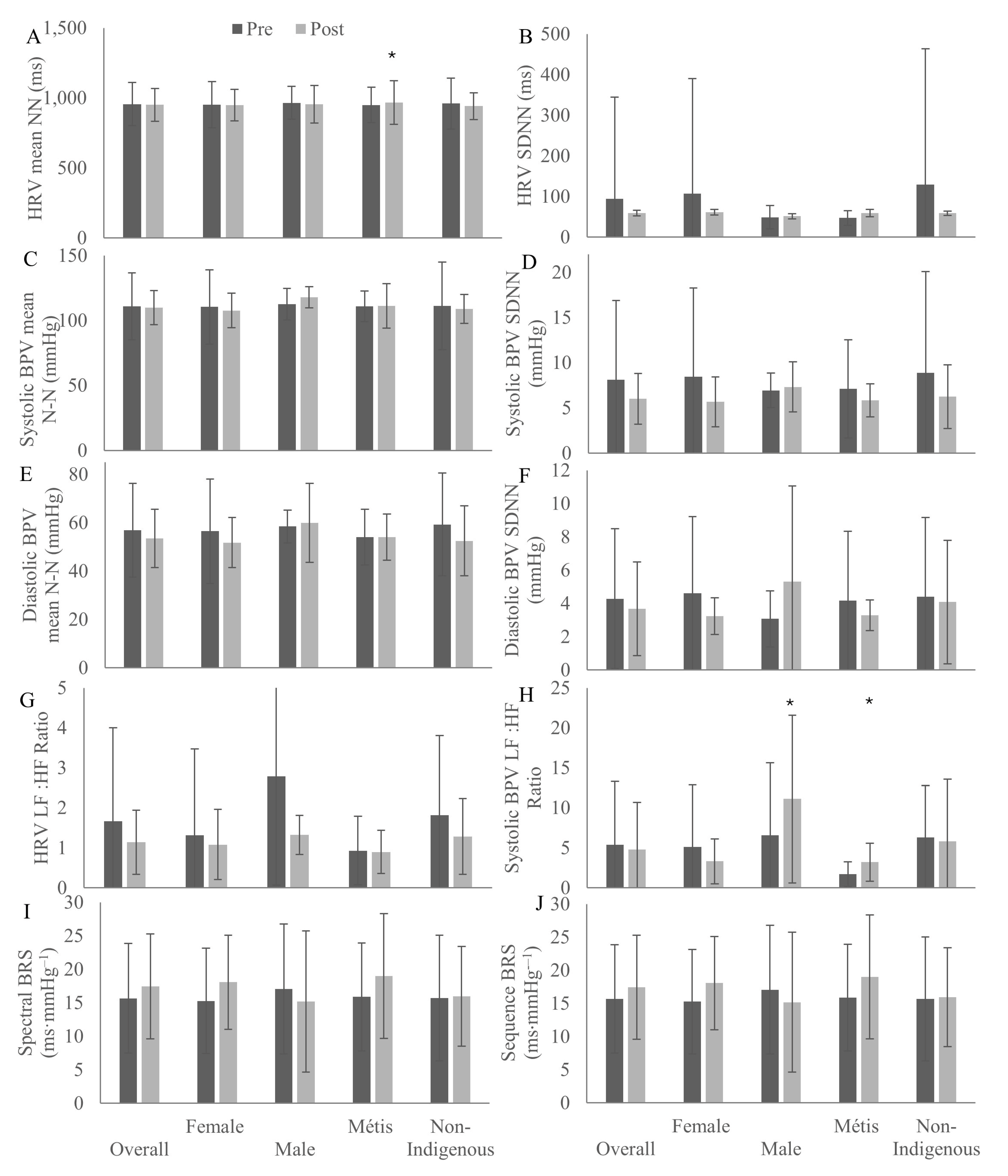

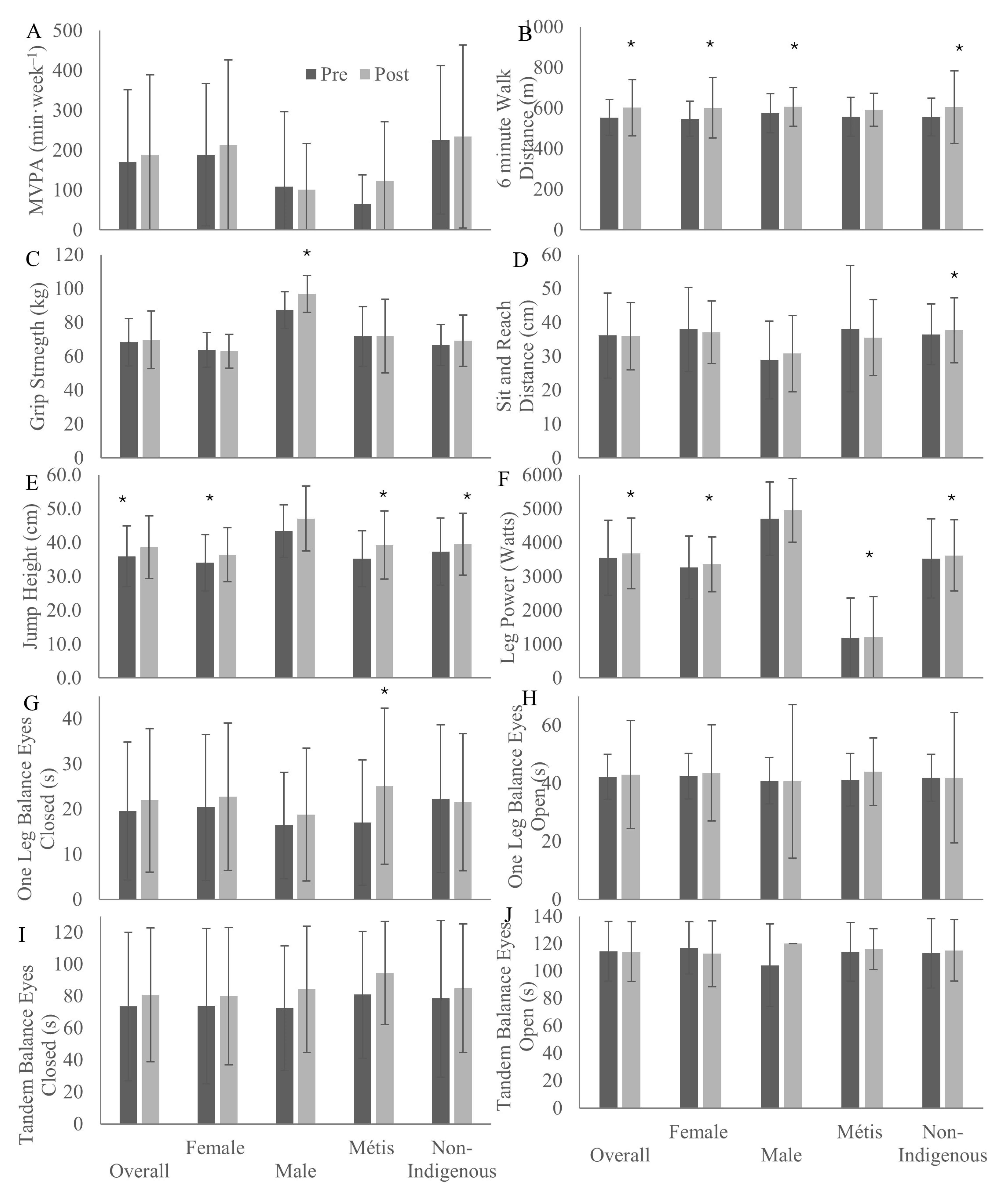

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Intervention Findings

3.2. Post-Intervention Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation

4.2. Strengths

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richmond, C.A.M.; Ross, N.A.; Bernier, J. Exploring Indigenous Concepts of Health: The Dimensions of Métis and Inuit Health; Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International (APRCi): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2007; p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- LaVallee, A. Converging Methods and Tools: A Métis Group Model Building Project on Tuberculosis; University of Saskatchewan: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Reading, J. Confronting the Growing Crisis of Cardiovascular Disease and Heart Health Among Aboriginal Peoples in Canada. Can. J. Cardiol. 2015, 31, 1077–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, P.J.; Bartlett, J.G.; Prior, H.J.; Sanguins, J.; Burchill, C.A.; Burland, E.M.; Carter, S. What is the comparative health status and associated risk factors for the Metis? A population-based study in Manitoba, Canada. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Olvera, A. Cultural Dance and Health: A Review of the Literature. Am. J. Health Educ. 2008, 39, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.G.; Iwasaki, Y.; Gottlieb, B.; Hall, D.; Mannell, R. Framework for Aboriginal-guided decolonizing research involving Métis and First Nations persons with diabetes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 2371–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, D.; Landy, R.; St Denys, R.; Ogilvie, K.; Lund, C.; Worthington, C. The Red River Cart Model: A Métis conceptualization of health and well-being in the context of HIV and other STBBI. Can. J. Public Health 2023, 114, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. CMAJ 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahindru, A.; Patil, P.; Agrawal, V. Role of Physical Activity on Mental Health and Well-Being: A Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e33475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quick, S. The Social Poetics of the Red River Jig in Alberta and Beyond: Meaningful Heritage and Emerging Performance. Ethnologies 2008, 30, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, S. Red River Jigging: “Traditional”, “Contemporary”, and in Unexpected Places. Can. Folk Music 2015, 49, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Macdougall, B. Land, Family and Identity: Contextualizing Metis Health and Well-Being; INational Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health: Prince George, BC, Canada, 2017; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Paquin, T.; Préfontaine, D.R.; Young, P. Traditional Métis Socialization and Entertainment. In Identity and Spritualism; Gabriel Dumont Institute of Native Studies and Applied Research, Ed.; Virtual Museium of Métis History and Culture: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2003; Volume Biography and Essay Collection, p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Hoye, B. Get or Red River Jig on: Métis Pavilion Bring Straditional Dance Back to Folklorama; CBC News: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez, O.; Johnson, S.; LaFleur, J.; Moore, S.; Ferguson, L.J.; Rodgers, C.; Chilibeck, P.; Foulds, H.J.A. “A spoke in the wheel”: Understanding experiences of ‘Métis Red River Jig’ dancers and impacts of the Métis Red River Jig on health and well-being. J. Exerc. Mov. Sport 2021, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Focus on Geography Series, 2021 Census of Population; 98-404-X2021001; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, M.; de Leeuw, S.; Lindsay, N.M. Determinants of Indigenous Peoples’ Health, Second Edition: Beyond the Social; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- The Royal Canadian Geographical Society/Canadian Geographic. Métis. In Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada; Canadian Geographic: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2018; Volume Métis. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, C.; Marshall, M.; Marshall, A. Two-Eyed Seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 2012, 2, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermine, W. The ethical space of engagement. Indig. Law J. 2007, 6, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Chapter 9: Research Involving the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples of Canada. In Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans—TCPS 2; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gabel, C.; Henry, B. National Métis Health Data Strategy and Principles; Métis National Council, Ed.; Métis National Council: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S.R.; Garba, I.; Figueroa-Rodríguez, O.L.; Holbrook, J.; Lovett, R.; Materechera, S.; Parsons, M.; Raseroka, K.; Rodriguez-Lonebear, D.; Rowe, R.; et al. The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Data Sci. J. 2020, 19, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, V.A.; Smart, N.A. Exercise training for blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2013, 2, e004473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP), Get Active Questionnaire. In Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology—Physical Activity Training for Health (CSEP-PATH); Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology, Ed.; Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) Risk Factors for Heart Disease, CAPI/CATI ed.; Statistics Canada, Ed.; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.D.; Unger Hu, K.A.; Mevi, A.A.; Hedderson, M.M.; Shan, J.; Quesenberry, C.P.; Ferrara, A. The multigroup ethnic identity measure-revised: Measurement invariance across racial and ethnic groups. J. Couns. Psychol. 2014, 61, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phinney, J. The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with adolescents and young adults from diverse groups. J. Adolesc. Res. 1992, 7, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Barker, P.R.; Colpe, L.J.; Epstein, J.F.; Gfroerer, J.C.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Normand, S.L.; Manderscheid, R.W.; Walters, E.E.; et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gully, S.M.; Eden, D. Validation of a New General Self-Efficacy Scale. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, F.; Mousavi, S.A.; Chaman, R.; Khosravi, A. [Validation of the World Health Organization-5 Well-Being Index; assessment of maternal well-being and its associated factors]. Turk Psikiyatr. Derg. Turk. J. Psychiatry 2015, 26, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fort, I.; Adoul, L.; Holl, D.; Kaddour, J.; Gana, K. Psychometric properties of the French version of the Multifactorial Memory Questionnaire for adults and the elderly. Can. J. Aging/ La Rev. Can. Du Vieil. 2004, 23, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, A.K.; Leach, L.; Vandermorris, S.; Rich, J.B. The measurement of participant-reported memory across diverse populations and settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Multifactorial Memory Questionnaire. Memory 2019, 27, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Distelberg, B.J.; Martin, A.v.S.; Borieux, M. A Deeper Look at the Social Support Index: A Multi-Dimensional Assessment. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2014, 42, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology-Physical Activity Training for Health (CSEP-PATH), 3rd ed.; Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Sullivan, M.J.; Thompson, P.J.; Fallen, E.L.; Pugsley, S.O.; Taylor, D.W.; Berman, L.B. The 6-minute walk: A new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1985, 132, 919–923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Behm, D.G.; Drinkwater, E.J.; Willardson, J.M.; Cowley, P.M. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology position stand: The use of instability to train the core in athletic and nonathletic conditioning. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 35, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjostrom, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foulds, H.J.; Bredin, S.S.; Warburton, D.E. The vascular health status of a population of adult Canadian Indigenous peoples from British Columbia. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2016, 30, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlicek, L.L.; Peterson, N.L. Robustness of the T Test: A Guide for Researchers on Effect of Violations of Assumptions. Psychol. Rep. 1974, 34, 1095–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffee, S. The Red River Jig; Gabriel Dumont Institute Publishing: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ouvrard, J. Hiding in Plain Sight: The Métis Nation. In Discover Library and Archives Canada: Your History, Your Documentary Heritage; Ouvrard, J., Ed.; Library and Archives Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Monchalin, R.; Smylie, J.; Bourgeois, C. “It’s not like I’m more Indigenous there and I’m less Indigenous here.”: Urban Métis women’s identity and access to health and social services in Toronto, Canada. Altern. Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2020, 16, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, F. The Emergence of the Métis Nation in Manitoba. In Métis Legacy: A Métis Historiographical and Annotated Bibliography; Barkwell, L.J., Dorion, L., Préfontaine, D.R., Eds.; Pemmican Publications: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2001; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Foulds, H.J.A.; Jamie, L.; Johnson, S.R.; Samantha, M.; McInnes, A.; Ferguson, L.J. “Community traditions, community kinship, language, and land bring me a lot of joy”: The importance of culture and social support in the health and wellbeing of Métis people. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2025, 20, 2512663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sischka, P.E.; Martin, G.; Residori, C.; Hammami, N.; Page, N.; Schnohr, C.; Cosma, A. Cross-National Validation of the WHO-5 Well-Being Index Within Adolescent Populations: Findings from 43 Countries. Assessment 2025, 30, 10731911241309452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekers, S.; Heine, J.; Thöne-Otto, A.I.; Finke, C. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and metamemory across the life span: Psychometric properties of the German Multifactorial Memory Questionnaire (MMQ). J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 4551–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reference Values for Arterial Stiffness’ Collaboration. Determinants of pulse wave velocity in healthy people and in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors: ‘establishing normal and reference values’. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 2338–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A.; Camm, A.J.; Cerutti, S.; Guzik, P.; Huikuri, H.; Lombardi, F.; Malik, M.; Peng, C.K.; Porta, A.; Sassi, R.; et al. Reference values of heart rate variability. Heart Rhythm 2017, 14, 302–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tank, J.; Baevski, R.M.; Fender, A.; Baevski, A.R.; Graves, K.F.; Ploewka, K.; Weck, M. Reference values of indices of spontaneous baroreceptor reflex sensitivity. Am. J. Hypertens. 2000, 13, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Master, A.M.; Dublin, L.I.; Marks, H.H. The normal blood pressure range and its clinical implications. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1950, 143, 1464–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, A.M.G.; Mota-Gomes, M.A.; Brandão, A.A.; Silveira, F.S.; Silveira, M.S.; Okawa, R.T.P.; Feitosa, A.D.M.; Sposito, A.C.; Nadruz, W., Jr. Reference values of office central blood pressure, pulse wave velocity, and augmentation index recorded by means of the Mobil-O-Graph PWA monitor. Hypertens. Res. 2020, 43, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Gan, L.; Zuo, L. Low-Frequency/High-Frequency Ratio Is a Predictor of Death and Hospitalization in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis: A Prospective Study. Blood Purif. 2024, 53, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Zhang, J. Psychometric characteristics of the Duke Social Support Index in a young rural Chinese population. Death Stud. 2012, 36, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ironside, A.; Ferguson, L.J.; Katapally, T.R.; Hedayat, L.M.; Johnson, S.R.; Foulds, H.J.A. Social determinants associated with physical activity among Indigenous adults at the University of Saskatchewan. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 46, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouxel, P.; Chandola, T. No Substitute for In-Person Interaction: Changing Modes of Social Contact during the Coronavirus Pandemic and Effects on the Mental Health of Adults in the UK. Sociology 2023, 58, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aston-Lebold, M. Online Socializing Vs. In-Person Socializing: Psychological Sense of Community is Equivalent. PhD. Thesis, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Chicago, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, N.; Gledhill, N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Jamnik, V.K.; Keir, P.J. Canadian musculoskeletal fitness norms. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 25, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foulds, H.J.; Bredin, S.S.; Warburton, D.E. The effectiveness of community based physical activity interventions with Aboriginal peoples. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Female | Male | Métis | Non-Indigenous | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed Study, n (%) | 32 (76.2) | 8 (80.0) | 14 (77.8) | 20 (71.4) | 40 (76.9) |

| Age, mean ± SD | 39 ± 16 | 40 ± 13 | 39 ± 16 | 39 ± 15 | 39 ± 15 |

| Male, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (100.0) | 3 (21.4) | 5 (25.0) | 8 (20.0) |

| Woman †, n (%) | 30 (93.8) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (78.6) | 13 (65.0) | 30 (75.0) |

| Man †, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (100.0) | 3 (21.4) | 5 (25.0) | 8 (20.0) |

| Métis, n (%) | 11 (34.4) | 3 (37.5) | 14 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (35.0) |

| First Nations, n (%) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.5) |

| Non-Indigenous, n (%) | 15 (46.9) | 5 (62.5) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (100.0) | 20 (50.0) |

| Education | |||||

| High School or Less, n (%) | 6 (18.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (28.6) | 1 (5.0) | 6 (15.0) |

| Trade School or College, n (%) | 11 (34.4) | 3 (37.5) | 4 (28.6) | 5 (25.0) | 14 (35.0) |

| At Least Some University, n (%) | 15 (46.9) | 5 (62.5) | 6 (42.9) | 14 (70.0) | 20 (50.0) |

| Full-time Student, n (%) | 15 (46.9) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (35.7) | 11 (55.0) | 18 (45.0) |

| Prior Experience with Red River Jig, n (%) | 7 (25.0) | 1 (10.0) | 5 (35.7) | 2 (10.0) | 8 (20.0) |

| Number of Classes Attended, mean ± SD | 7.7 ± 1.1 | 8.0 ± 0.5 | 7.7 ± 1.0 | 7.9 ± 0.8 | 7.8 ± 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mainra, N.K.; Moore, S.J.; LaFleur, J.; Oates, A.R.; Selinger, G.; Rolfes, T.T.; Sullivan, H.; Fatima, M.; Foulds, H.J.A. The Effects of the Red River Jig on the Wholistic Health of Adults in Saskatchewan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081225

Mainra NK, Moore SJ, LaFleur J, Oates AR, Selinger G, Rolfes TT, Sullivan H, Fatima M, Foulds HJA. The Effects of the Red River Jig on the Wholistic Health of Adults in Saskatchewan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081225

Chicago/Turabian StyleMainra, Nisha K., Samantha J. Moore, Jamie LaFleur, Alison R. Oates, Gavin Selinger, Tayha Theresia Rolfes, Hanna Sullivan, Muqtasida Fatima, and Heather J. A. Foulds. 2025. "The Effects of the Red River Jig on the Wholistic Health of Adults in Saskatchewan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081225

APA StyleMainra, N. K., Moore, S. J., LaFleur, J., Oates, A. R., Selinger, G., Rolfes, T. T., Sullivan, H., Fatima, M., & Foulds, H. J. A. (2025). The Effects of the Red River Jig on the Wholistic Health of Adults in Saskatchewan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1225. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081225