“It All Starts by Listening:” Medical Racism in Black Birthing Narratives and Community-Identified Suggestions for Building Trust in Healthcare

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Today Not Tomorrow Pregnancy and Infant Support Program

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Medical Racism in Black Birthing Experiences

“It was just—this one lady took away all of my power, and then when I fought for it afterwards because I was angry and I was scared. And when I fought for it afterwards, I was painted as somebody—even going into it, the day that I went into labor, because I wanted a spontaneous labor, and so the c-section was not urgent, but, like, they wanted to get it done faster. I was painted as a difficult patient.”

“So I probably wouldn’t trust them [doctors who aren’t Black] at all. There’s probably nothing they can do to make me trust them, to make me more comfortable or nothing like that. I would probably ask them 50 million questions. I would always go back to somebody I know to go on the internet, research, things like that.”

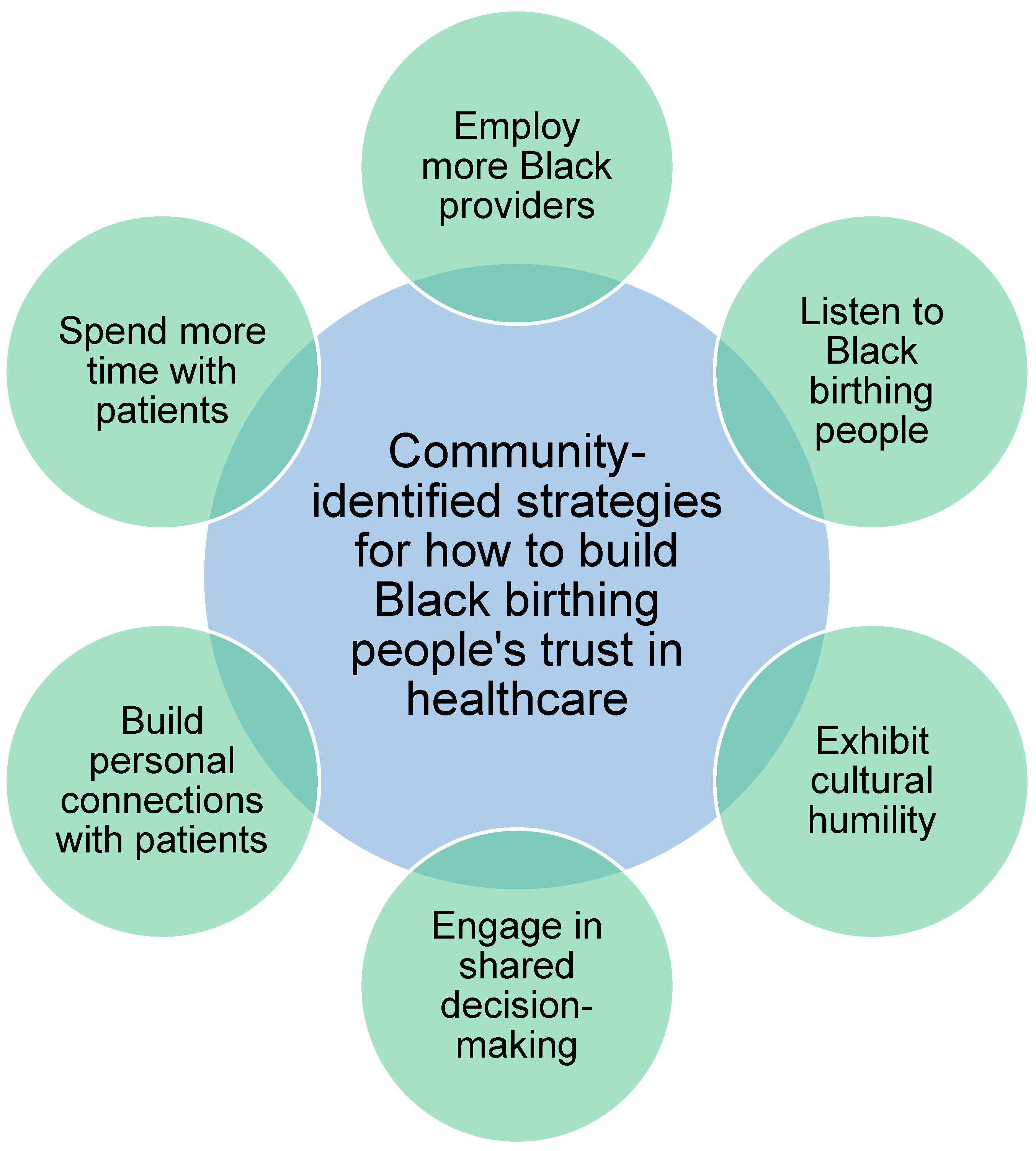

3.2. Strategies for Building Trust

3.2.1. Employ More Black Providers

“And so, to be able to talk to a provider who gets it and like understands that layer of stress that’s constantly on top of everything else, it’s really nice to just be able to talk with someone about that and understanding being a person of color, and so, my primary care doctor, she is a person of color, and that’s why I sought her out, and I have a wonderful—every time I go to her for a visit, it’s so nice, it’s like therapeutic in a way.”

3.2.2. Listen to Black Birthing People

“I do get that obviously the doctors are well-trained, well-educated, but I also believe that the patient, the person in front of you, also knows their body better than you do and better than anyone else does. So, if they are coming in with a viewpoint that you should listen, you should definitely listen and either try and compromise or work through it as opposed to just dismissing the cares of that person or actively going against what the client or the patient wants simply because of your own internal biases.”

“And it doesn’t matter how well you speak to your provider, how eloquently you can say what you need, you’re just a Black body. I mean, I know from myself that I’ve gone in to see providers that I realized that this will be the last time that I see this person, and I will find someone else. They’re not even listening to anything I’m saying or anything that I know that is going on in my body.”

“We have to believe Black moms when we say that we’re, you know, in pain or we have to recognize that little Black boys aren’t just strong and big, but they’re also precious and tender and in need of, you know, that, the same care that someone would give to a little girl or a little child that’s not Black.”

3.2.3. Exhibit Cultural Humility

3.2.4. Engage in Shared Decision-Making

“And my nurses were really informative. They were giving me the ins and outs of everything because that’s what I needed. I needed to know, ‘what are you doing?,’ ‘Why are you doing it?,’ ‘What is it going to do for me?,’ ‘How is it going to help me?,’ ‘How is it going to affect [my baby] before she’s born?’ And I think having providers be able to do that even more throughout your—the process, especially when you’re going to appointments. And just giving you the details necessary, that you need to feel comfortable and know like, oh, I do have options.”

3.2.5. Build Personal Connections with Patients

“I’ve noticed a difference in providers who, like, when I’m starting to work with them, they ask me not just what I do for work, but they ask me about my family and where I’m from and how I’m enjoying or how living in [this city] is. Just having more of a personal connection with me really helps me to build trust with the provider. And I’ve also had providers who, like, really just jumped into the visit and don’t really take the time to engage, ask, like a real person, develop any sort of connection. And so, for those providers, I just am less likely to speak up or to want to talk with them because it seems like they don’t really care. So just like at a basic level, taking time to get to know someone.”

“Like, if it’s good eye contact and they pronounce names correctly, or they’re asking questions like, ‘how are you doing’ and listening, and then maybe the next time they come in the room, they follow up…But I think it just goes back to being seen and being heard, and feel like you see me as an individual, and not just the third delivery of the day.”

3.2.6. Spend More Time with Patients

“Our [midwife] appointments were so comprehensive…our appointments would be each like an hour long or more, an hour or more long. And she would ask me about my entire being.”

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TNT-PISP | Today Not Tomorrow Pregnancy and Infant Support Group |

References

- Bridges, K.M. Racial Disparities in Maternal Mortality. N. Y. Univ. Law Rev. 2020, 95, 1229–1318. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Office of Minority Health. Infant Mortality and African Americans; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services Office of Minority Health: Rockville, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, M.Z.; García, J.J.; Mitchell, U.; Dellor, E.D.; Bradford, N.J.; Truong, M. Racism and Structural Violence: Interconnected Threats to Health Equity. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 676783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.; Crear-Perry, J.; Richardson, L.; Tarver, M.; Theall, K. Separate and Unequal: Structural Racism and Infant Mortality in the US. Health Place 2017, 45, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, L.; Rao, A.; Artiga, S.; Published, U.R. Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: Current Status and Efforts to Address Them; KFF: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamoud, Y.A.; Cassidy, E.; Fuchs, E.; Womack, L.S.; Romero, L.; Kipling, L.; Oza-Frank, R.; Baca, K.; Galang, R.R.; Stewart, A.; et al. Vital Signs: Maternity Care Experiences—United States, April 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attanasio, L.; Kozhimannil, K.B. Patient-Reported Communication Quality and Perceived Discrimination in Maternity Care. Med. Care 2015, 53, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treder, K.; White, K.O.; Woodhams, E.; Pancholi, R.; Yinusa-Nyahkoon, L. Racism and the Reproductive Health Experiences of U.S.-Born Black Women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 139, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Glazer, K.B.; Sofaer, S.; Balbierz, A.; Howell, E.A. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity: A Qualitative Study of Women’s Experiences of Peripartum Care. Women’s Health Issues 2021, 31, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick, M.; Oshewa, O.; Janevic, T.; Wang-Koehler, E.; Zeitlin, J.; Howell, E.A. Experiences of Care, Racism, and Communication of Postpartum Black Women Readmitted After Delivery. O&G Open 2024, 1, 028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janevic, T.; Piverger, N.; Afzal, O.; Howell, E.A. “Just Because You Have Ears Doesn’t Mean You Can Hear”—Perception of Racial-Ethnic Discrimination During Childbirth. Ethn. Dis. 2020, 30, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.; Liu, F.; Keele, R.; Spencer, B.; Kistner Ellis, K.; Sumpter, D. An Integrative Review of the Perinatal Experiences of Black Women. Nurs. Women’s Health 2022, 26, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.; Green, C.; Richardson, L.; Theall, K.; Crear-Perry, J. “Look at the Whole Me”: A Mixed-Methods Examination of Black Infant Mortality in the US through Women’s Lived Experiences and Community Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odems, D.S.; Czaja, E.; Vedam, S.; Evans, N.; Saltzman, B.; Scott, K.A. “It Seemed like She Just Wanted Me to Suffer”: Acts of Obstetric Racism and Birthing Rights Violations against Black Women. SSM—Qual. Res. Health 2024, 6, 100479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, O.; Karvonen, K.L.; Gonzales-Hinojosa, M.D.; Lewis-Zhao, S.; Washington, T.; McLemore, M.R.; Rogers, E.E.; Franck, L.S. Parents Experiences of Racism in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Patient Exp. 2024, 11, 23743735241272226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, H.A. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present; First Anchor Books: New York, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-7679-1547-2. [Google Scholar]

- Okoro, O.N.; Hillman, L.A.; Cernasev, A. “We Get Double Slammed!”: Healthcare Experiences of Perceived Discrimination among Low-Income African-American Women. Women’s Health 2020, 16, 1745506520953348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C. Black Americans’ Views About Health Disparities, Experiences with Health Care; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Musa, D.; Schulz, R.; Harris, R.; Silverman, M.; Thomas, S.B. Trust in the Health Care System and the Use of Preventive Health Services by Older Black and White Adults. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benkert, R.; Cuevas, A.; Thompson, H.S.; Dove-Medows, E.; Knuckles, D. Ubiquitous Yet Unclear: A Systematic Review of Medical Mistrust. Behav. Med. 2019, 45, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas, A.G.; O’Brien, K.; Saha, S. African American Experiences in Healthcare: “I Always Feel like I’m Getting Skipped over”. Health Psychol. 2016, 35, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, V.N. Under the Shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and Health Care. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 1773–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Brown, A.L.; Jones, F.; Jones, L.; Withers, M.; Ciesielski, K.M.; Franks, J.M.; Wang, C. “I’m Not Going to Be a Guinea Pig:“ Medical Mistrust as a Barrier to Male Contraception for Black American Men in Los Angeles, CA. Contraception 2021, 104, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, T.J.; Ely, D.M.; Driscoll, A.K. State Variations in Infant Mortality by Race and Hispanic Origin of Mother, 2013–2015; Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Today Not Tomorrow, Inc. Available online: https://clubtnt.org/todayNotTomorrow.html (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Urban and Rural Counties. Available online: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/wish/urban-rural.htm (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- QuickFacts: Dane County, Wisconsin. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/danecountywisconsin/RHI125223 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Evans-Winters, V.E. Black Feminism in Qualitative Inquiry: A Mosaic for Writing Our Daughter’s Body, 1st ed.; Series: Futures of Data Analysis in Qualitative Research; Routledge: Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-351-04607-7. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2022, 9, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B.B.; Vedam, S.; Illuzzi, J.; Cheyney, M.; Kennedy, H.P. Inequities in Quality Perinatal Care in the United States during Pregnancy and Birth after Cesarean. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.M.; Young, Y.-Y.; Bass, T.M.; Baker, S.; Njoku, O.; Norwood, J.; Simpson, M. Racism Runs Through It: Examining The Sexual And Reproductive Health Experience Of Black Women In The South: Study Examines the Sexual and Reproductive Health Experiences of Black Women in the South. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper Owens, D.B. Medical Bondage: Race, Gender, and the Origins of American Gynecology; Paperback Edition; The University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-8203-5475-0. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, J.E.; Upton, R.D.; Hassett, T.C.; Lee, H.; Nouri, Z.; Dill, M. Black Representation in the Primary Care Physician Workforce and Its Association With Population Life Expectancy and Mortality Rates in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e236687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, D.P. Historical Trends in the Representativeness and Incomes of Black Physicians, 1900–2018. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2022, 37, 1310–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zapata, J.Y.; Swan, L.E.T.; White, M.S.; Frizell-Thomas, B.; Oniah, O. “It All Starts by Listening:” Medical Racism in Black Birthing Narratives and Community-Identified Suggestions for Building Trust in Healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081203

Zapata JY, Swan LET, White MS, Frizell-Thomas B, Oniah O. “It All Starts by Listening:” Medical Racism in Black Birthing Narratives and Community-Identified Suggestions for Building Trust in Healthcare. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081203

Chicago/Turabian StyleZapata, Jasmine Y., Laura E. T. Swan, Morgan S. White, Baillie Frizell-Thomas, and Obiageli Oniah. 2025. "“It All Starts by Listening:” Medical Racism in Black Birthing Narratives and Community-Identified Suggestions for Building Trust in Healthcare" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081203

APA StyleZapata, J. Y., Swan, L. E. T., White, M. S., Frizell-Thomas, B., & Oniah, O. (2025). “It All Starts by Listening:” Medical Racism in Black Birthing Narratives and Community-Identified Suggestions for Building Trust in Healthcare. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081203