Reimagining Partnerships Between Black Communities and Academic Health Research Institutions: Towards Equitable Power in Engagement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Strategy and Participant Criterion

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Quality Assurance and Researcher Reflexivity

3. Results

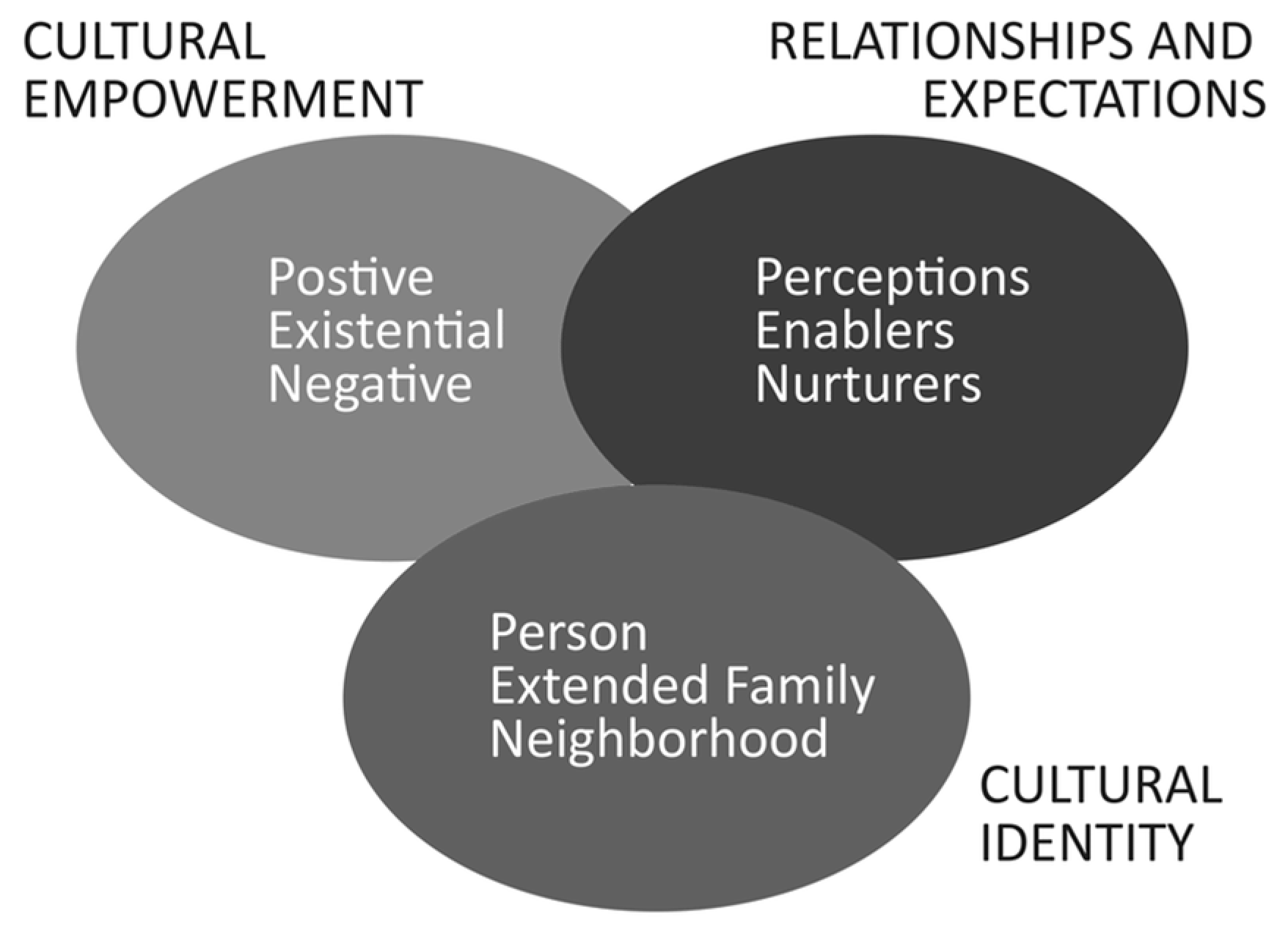

3.1. Debunking Cultural Deficits Framing (Domain 1: Cultural Empowerment)

“[A] common belief from White researchers is that Black people just aren’t interested in or capable of being a part of health research.”

“I feel like why we ended up getting excluded from so much research is that they just don’t want to do the work of acknowledging all of the barriers.”

3.2. Reimagined Health Research Topics (Domain 1: Cultural Empowerment)

“It’s about being able to give voice to your desires and pleasures or needs or wants.”

3.3. Reimagined Health Research Design and Processes (Domain 1: Cultural Empowerment)

“That’s all it boils down to, like how are we educating communities directly, I think it does have to come from us, the Black researchers, the Black professionals, because there’s so much mistrust within our community.”

3.4. Reimagined Health Research Outcomes (Domain 1: Cultural Empowerment)

“I feel like researchers shouldn’t just conduct research, they should also be prepared to take measures that would improve the reason they were there.”

“Not just getting information but providing solutions.”

3.5. Reimagined Resources Needed (Domain 1: Cultural Empowerment)

“Financial. I need money to survive to eat, like, I need to pay people. I believe in paying people equitably for their experiences, not just their education as well.”

3.6. Health Research Motivation (Domain 2: Relationships and Expectations)

“I come from people who worked for the improvement and the betterment of Black folks, whatever that look like… so I follow in those footsteps.”

“I had this motivation to be involved when it comes to research…because of my mom. Because of that [health] situation, I wouldn’t want any other person to ended up in that dire situation.”

“The first step in getting to a self-sustaining Black society is being healthy. Because if we’re struggling with diabetes and cardiovascular disease and all these things, you know, preventable or not preventable, unmanaged mental illness, I don’t think we can be as great as we could be.”

3.7. Reimagined Community Role (Domain 2: Relationships and Expectations)

“Hopefully, I pray I become leader of a research team one day.”

“I would like to have my hands in it. So I would get to be engaged with the living data of how people would utilize… like what would it look like for them to practice this theory in real time.”

3.8. Reimagined Academic Role (Domain 2: Relationships and Expectations)

“They should give us money because they have so much. They should also I would say…[provide] guidance or like technical assistance if needed. Not an overseer, not a leader. I really think like, if I need you, if I needed to call to get an SPSS package, I could, and they could send me a link and I can download it for free.”

“I think it would be important to have an investment from academic researchers…who are invested in the outcome. So being able to have researchers who see the importance of providing ways of thinking and practice towards liberation and freedom. If you are aligned with that, then yes, it would make sense that you would be part of this research. You want to do more of the community work, it would make sense that you would participate.”

3.9. Black Identity (Domain 3: Cultural Identity)

“Being Black is not a monolith. We are all so vastly different.”

“[I’m] kind of grappling in a space of being in between not having the privileges of other people, but definitely having more privileges than the people in the same—I guess if you want to look at the basement metaphor of intersectionality—in the same basement as me.”

3.10. Black Community Belonging and Meaning-Making (Domain 3: Cultural Identity)

“When I hear Black community, the first thing that comes to my mind is its strengths. Our Black community is mostly based on intellect, strength. And we have this spirit of togetherness, you know… we’re proud about what we know is right.

“It really is a lot of like unity, but there’s also so much division as well… [there are] so many things that are being used as dividers in our community, whether it’s colorism, whether it’s sexual orientation, whether it’s cis, trans, there’s a lot out there.”

“I’m African descent. I was born and raised here. My parents are from Cameroon. So for me just having that identity…am I American and am I African enough? Am I Black enough?”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Building the research capacity of Predominately Black Institutions (PBIs) and Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). This should be achieved through federal investment and implementing policy changes to ensure that more PBIs and HBCUs receive R1 “Very high research activity” designations.

- Investing in diversifying health workforce pathways, from K-12 education to academic health leadership, to increase the number of Black health researchers. This also includes closing the funding gap to ensure more Black principal investigators are funded to lead research on racial health equity.

- Identifying and removing systemic barriers in awareness, enrollment, and retention of Black research participants in health and biomedical research. This also includes improving public awareness of existing patient and community-engaged research advisory opportunities, such as the Food and Drug Administration’s Patient Representative Program and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute’s Advisory Panels.

- Building the research capacity of Black communities to engage in community-led research (community efficacy). Building community efficacy requires identifying and removing procedural and bureaucratic injustices that many Black-led and managed community-based organizations and coalitions experience in accessing health research funding. It also requires innovative research funding models (like public–private partnerships, cross-agency federal funding approaches, federal challenges and prize competitions, and philanthropic social impact investments) to grow community-based health research and data infrastructure.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CER | Community-Engaged Research |

| CAP | Community–Academic Partnership |

References

- Wallerstein, N.; Duran, B.; Oetzel, J.G.; Minkler, M. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Key, K.D.; Furr-Holden, D.; Lewis, E.Y.; Cunningham, R.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Johnson-Lawrence, V.; Selig, S. The Continuum of Community Engagement in Research: A Roadmap for Understanding and Assessing Progress. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2019, 13, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Principles of Community Engagement, Second Edition. 2011. Available online: https://ictr.johnshopkins.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/CTSAPrinciplesofCommunityEngagement.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Washington, H.A. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hoberman, J. Black and Blue: The Origins and Consequences of Medical Racism; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, D. Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty; Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Washington, H.A. Carte Blanche: The Erosion of Medical Consent; Columbia Global Reports: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, H.J.; Chief, C.; Jiménez, D.; Begay, A.; Milner, T.F.; Sullivan, S.; Torres, E.; Remiker, M.; Samarron Longorio, A.E.; Sabo, S.; et al. Voices of Community Partners: Perspectives Gained from Conversations of Community-Based Participatory Research Experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnstein, S. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, R.; Pyne, J.; Bauer, G.; Munro, L.; Giambrone, B.; Hammond, R.; Scanlon, K. ‘Community control’ in CBPR: Challenges experienced and questions raised from the Trans PULSE project. Action Res. 2013, 11, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchida, C.V.; Stout, M. Disempowerment versus empowerment: Analyzing power dynamics in professional community development. Community Dev. 2023, 55, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, S. Power: A Radical View, 3rd ed.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa, J. Finding the Spaces for Change: A Power Analysis. IDS Bull. 2006, 37, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaventa, J.; Cornwall, A. Challenging the Boundaries of the Possible: Participation, Knowledge and Power. IDS Bull. 2006, 37, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B.A.; Checkoway, B.; Schulz, A.; Zimmerman, M. Health Education and Community Empowerment: Conceptualizing and Measuring Perceptions of Individual, Organizational, and Community Control. Health Educ. Q. 1994, 21, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follett, M.P. Creative Experience; Longmans, Green and Company: London, UK, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Dowding, K.M. Power; U of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Purdy, J.M. A Framework for Assessing Power in Collaborative Governance Processes. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathie, A.; Cameron, J.; Gibson, K. Asset-based and citizen-led development: Using a diffracted power lens to analyze the possibilities and challenges. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2017, 17, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toomey, A.H. Empowerment and disempowerment in community development practice: Eight roles practitioners play. Community Dev. J. 2011, 46, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson-Brown, T. It’s Not Irony, it’s Interest Convergence: A CRT Perspective on Racism as Public Health Crisis Statements. J. Law Med. Ethics 2022, 50, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lett, E.; Adekunle, D.; McMurray, P.; Asabor, E.N.; Irie, W.; Simon, M.A.; Hardeman, R.; McLemore, M.R. Health Equity Tourism: Ravaging the Justice Landscape. J. Med. Syst. 2022, 46, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, R.; Stefancic, J. Critical Race Theory. Vol. Fourth Edition: An Introduction; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D.A. Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma. Harv. Law Rev. 1980, 93, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto-Manning, M. Critical narrative analysis: The interplay of critical discourse and narrative analyses. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2014, 27, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudshoorn, A.; Sangster Bouck, M.; McCann, M.; Zendo, S.; Berman, H.; Banninga, J.; Le Ber, M.J.; Zendo, Z. A critical narrative inquiry to understand the impacts of an overdose prevention site on the lives of site users. Harm Reduct. J. 2021, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solórzano, D.G.; Yosso, T.J. Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qual. Inq. 2002, 8, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwelunmor, J.; Newsome, V.; Airhihenbuwa, C.O. Framing the impact of culture on health: A systematic review of the PEN-3 cultural model and its application in public health research and interventions. Ethn. Health 2014, 19, 20–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airhihenbuwa, C.O. Of Culture and Multiverse: Renouncing “the Universal Truth” in Health. J. Health Educ. 1999, 30, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airhihenbuwa, C.O. Perspectives on AIDS in Africa: Strategies for prevention and control. AIDS Educ. Prev. 1989, 1, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa, C.O. Health and Culture: Beyond the Western Paradigm; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; Volume Eweb:148042. [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa, C.O. Healing Our Differences: The Crisis of Global Health and the Politics of Identity; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport. Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Davey, L.; Jenkinson, E. Doing Reflexive Thematic Analysis. In Supporting Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research; Bager-Charleson, S., McBeath, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, R.E. Qualitative Interview Questions: Guidance for Novice Researchers. Qual. Rep. 2020, 25, 3185–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverack, G. Improving Health Outcomes through Community Empowerment: A Review of the Literature. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2006, 24, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Power: The Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954–1984; Penguin UK: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Foundation, R.W.J. Building Community Power to Advance Health Equity. 2023. Available online: https://www.rwjf.org/en/our-vision/focus-areas/Features/building-community-power-to-advance-health-equity.html (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Popay, J.; Whitehead, M.; Ponsford, R.; Egan, M.; Mead, R. Power, control, communities and health inequalities I: Theories, concepts and analytical frameworks. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 36, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iton, A.; Ross, R.K.; Tamber, P.S. Building Community Power to Dismantle Policy-Based Structural Inequity in Population Health: Article describes how to build community power to dismantle policy-based structural inequity. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 1763–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, P.W.; Gupta, J.; Haapanen, K.; Balmer, B.; Wiley, K.T.; Bachelder, A. Developing Community Power for Health Equity: A landscape Analysis of Current Research and Theory; Vanderbilt University: Nashville, TN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Haugaard, M. Rethinking the four dimensions of power: Domination and empowerment. J. Political Power 2012, 5, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, J.C.; Fleming, P.J.; Petteway, R.J.; Givens, M.; Pollack Porter, K.M. Power up: A call for public health to recognize, analyze, and shift the balance in power relations to advance health and racial equity. Am. J. Public Health 2023, 113, 1079–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, K.R. Determining the Sample in Qualitative Research. Online Submiss. 2021, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, H. Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qual. Res. J. 2011, 1, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoine-LaVigne, D.; Hayes, T.; Fortenberry, M.; Ohikhuai, E.; Addison, C.; Mozee, S., Jr.; McGill, D.; Shanks, M.L.; Roby, C.; Jenkins, B.W.C.; et al. Trust and biomedical research engagement of minority and under-represented communities in Mississippi, USA. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denyse, T.; Martin, K.J.; Stanton, A.L. The Ubuntu Approach in Project SOAR (Speaking Our African American Realities): Building a robust community-academic partnership and culturally curated focus groups. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 314, 115452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Public Health Association. Racism Declarations; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S.B.; Quinn, S.C.; Butler, J.; Fryer, C.S.; Garza, M.A. Toward a Fourth Generation of Disparities Research to Achieve Health Equity. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Characteristic | n = 12 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0.0 |

| Asian | 0 | 0.0 |

| Black or African American | 10 | 83.3 |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 0 | 0.0 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 0.0 |

| White | 0 | 0.0 |

| Multiracial or Multiethnic | 2 | 16.6 |

| Gender | ||

| Cisgender Female | 9 | 75.0 |

| Cisgender Male | 2 | 16.7 |

| Nonbinary | 1 | 8.3 |

| Geographic Region | ||

| Mid-Atlantic | 2 | 16.7 |

| Midwest | 2 | 16.7 |

| Northeast | 1 | 8.3 |

| Southeast | 4 | 33.3 |

| Southwest | 1 | 8.3 |

| West | 2 | 16.7 |

| Sub-Topic | Main Question |

|---|---|

| Prompt: Imagine you had unlimited power, resources, and money. | |

| Community Agency | What health topics would you want to research? |

| If you were able to conduct research on the health topics you just described, what role would you want to play in that research? | |

| What types of data would you want to collect and analyze? | |

| What types of research products would you want to produce? | |

| Community Efficacy | What types of resources would make it possible for you to conduct that research? |

| What knowledge and skills would you need to conduct that research? | |

| Community Solidarity | What role, if any, would you want academic researchers to play in that research? |

| What support, if any, would you want academic researchers and research institutions to provide? | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ameen, K.; Airhihenbuwa, C.O.; Freire, K.; Ponder, M.; Hosein, A. Reimagining Partnerships Between Black Communities and Academic Health Research Institutions: Towards Equitable Power in Engagement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060921

Ameen K, Airhihenbuwa CO, Freire K, Ponder M, Hosein A. Reimagining Partnerships Between Black Communities and Academic Health Research Institutions: Towards Equitable Power in Engagement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060921

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmeen, Khadijah, Collins O. Airhihenbuwa, Kimberley Freire, Monica Ponder, and Alicia Hosein. 2025. "Reimagining Partnerships Between Black Communities and Academic Health Research Institutions: Towards Equitable Power in Engagement" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060921

APA StyleAmeen, K., Airhihenbuwa, C. O., Freire, K., Ponder, M., & Hosein, A. (2025). Reimagining Partnerships Between Black Communities and Academic Health Research Institutions: Towards Equitable Power in Engagement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060921