Differences in Personal Recovery Among Individuals with Severe Mental Disorders in Private and Supported Accommodations: An Exploratory Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

- (1)

- Employment outside the South Verona CMHS (n = 15),

- (2)

- Refusal to participate (n = 8),

- (3)

- Inability to recruit a suitable service user (n = 3).

2.3. Clinical Tools and Their Characteristics

- (1)

- Physical and mental health: managing mental health, self-care, addictive behavior

- (2)

- Activities and functioning: living skills, work, responsibilities

- (3)

- Self-image: identity and self-esteem, trust and hope

- (4)

- Networks: social networks, relationships

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Mental Health Professionals’ Assessments

3.2. People with SMD Characteristics at Baseline

3.3. Clinical and Functional Changes of People with SMD from Baseline to Follow-Up According to Accommodation

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAN | Camberwell Assessment of Need |

| CMHS | community mental health service |

| FPS | Personal and Social Functioning Scale |

| HoNOS | Health of the Nation Outcome Scale |

| MHRS | Mental Health Recovery Star |

| MPR | Monitoring of the Path of Rehabilitation |

Appendix A

| Private Accommodation | Supported Accommodation | p-Value t Test or Fisher’s Exact Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male | 4 (28.6%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0.245 |

| Discipline Medical doctor Support worker Nurse/basic carer Psychologist | 6 (42.9%) 4 (28.6%) 2 (14.3%) 2 (14.3%) | 3 (27.3%) 4 (36.4%) 2 (18.2%) 2 (18.2%) | 0.885 |

| Months working in mental health, mean (SD) | 112.4 (105.7) | 168.6 (139.1) | 0.262 |

| BL Private Accommodation (N = 14) | FU Private Accommodation (N = 9) | p-Value Fisher’s Exact Test | BL Supported Accommodation (N = 11) | FU Supported Accommodation (N = 11) | p-Value Fisher’s Exact Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

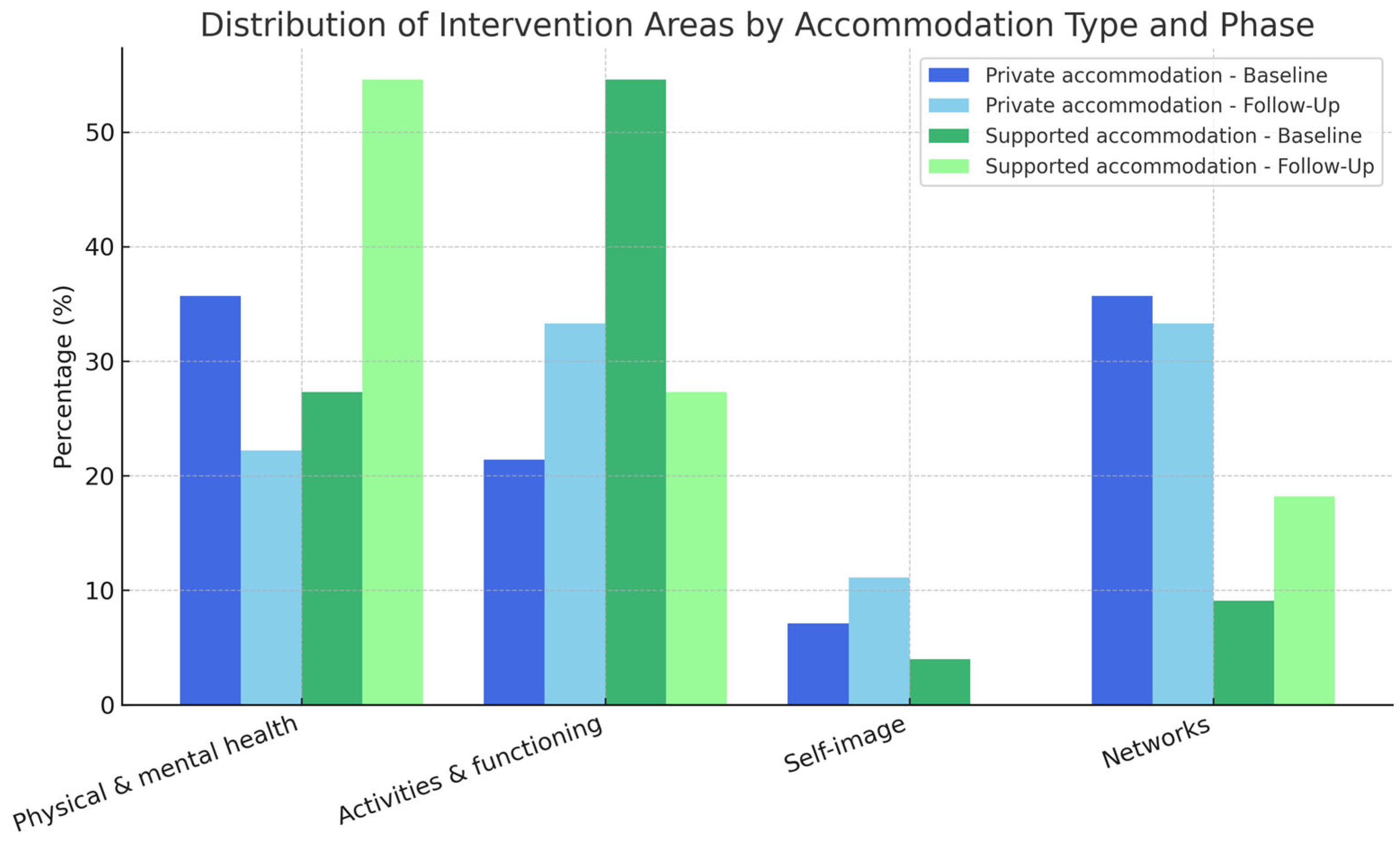

| Area/s of intervention | ||||||

| Physical and mental health | 5 (35.7%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0.011 | 3 (27.3%) | 5 (54.6%) | 0.176 |

| Activities and functioning | 3 (21.4%) | 3 (33.3%) | 6 (54.6%) | 3 (27.3%) | ||

| Self-image | 1 (7.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Networks | 5 (35.7%) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 2 (18.2%) |

References

- Reed, G.M. What’s in a name? Mental disorders, mental health conditions and psychosocial disability. World Psychiatry 2024, 23, 209–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Europe. The WHO European Framework for Action to Achieve the Highest Attainable Standard of Health for Persons with Disabilities 2022–2030; WHO Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- WHO. Helping People with Severe Mental Disorders Live Longer and Healthier Lives; WHO Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Parabiaghi, A.; Bonetto, C.; Ruggeri, M.; Lasalvia, A.; Leese, M. Severe and persistent mental illness: A useful definition for prioritizing community-based mental health service interventions. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2006, 41, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killaspy, H. The ongoing need for local services for people with complex mental health problems. Psychiatr. Bull. 2014, 38, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Council of the European Union. Disability in the EU: Facts and Figures; European Council of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- Caldas de Almeida, J.M.; Killaspy, H. Long-Term Mental Health Care for People with Severe Mental Disorders. Report for the European Commission. 2011. Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/document/download/53cb0f32-1746-4a25-ad0e-228a68b37fe5_en (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- United Nations. UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. United Nations General Assembly A/61/611. 2006. Available online: https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2019).

- Taylor Salisbury, T.; Killaspy, H.; King, M. An international comparison of the deinstitutionalisation of mental health care: Development and findings of the Mental Health Services Deinstitutionalisation Measure (MENDit). BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, A. The key pillars of psychosocial disability: A European perspective on challenges and solutions. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1574301. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1574301/full (accessed on 1 June 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NICE. Rehabilitation for Adults with Complex Psychosis; NICE: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, M.; Amering, M.; Farkas, M.; Hamilton, B.; O’HAgan, M.; Panther, G.; Perkins, R.; Shepherd, G.; Tse, S.; Whitley, R. Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SLAM/SWLSTG. Recovery is for All: Hope, Agency and Opportunity in Psychiatry; A Position Statement by Consultant Psychiatrists; South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp, C.A.; Goscha, R.J. The Strengths Model A Recovery-Oriented Approach to Mental Health Services, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Beale, V.; Lambric, T. The Recovery Concept: Implementation in the Mental Health System; Community Support Program Advisory Committee: Columbus, OH, USA, 1995.

- Farkas, M.; Gagne, C.; Anthony, W.; Chamberlin, J. Implementing recovery oriented evidence based programs: Identifying the critical dimensions. Community Ment. Health J. 2005, 41, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deegan, P.E. Recovery as a journey of the heart. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 1996, 19, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leamy, M.; Bird, V.; Le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. A conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killaspy, H.; Harvey, C.; Brasier, C.; Brophy, L.; Ennals, P.; Fletcher, J.; Hamilton, B. Community-based social interventions for people with severe mental illness: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of recent evidence. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 96–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, A.; Ruggeri, M. The impact on psychiatric rehabilitation of recovery oriented-practices. J. Psychopathol. 2020, 26, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Liberman, R.P. Recovery from Disability: Manual of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Available online: https://catalog.nlm.nih.gov/permalink/01NLM_INST/1o1phhn/alma9913063143406676 (accessed on 4 June 2019).

- WHO—Regional Office for Europe. The European Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; p. 19.

- WHO—European Ministerial Conference on Mental Health. Mental Health Declaration for Europe “Facing the Challenges, Building Solution”. 2005; pp. 81–84. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/326566 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Mccabe, R.; Whittington, R.; Cramond, L.; Perkins, E. Contested understandings of recovery in mental health. J. Ment. Health 2018, 27, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carozza, P. Principi di Riabilitazione Psichiatrica: Per un Sistema di Servizi Orientato alla Guarigione, 9th ed.; Strumenti per il Lavoro Psico-Sociale ed Educativo; FrancoAngeli: Milan, Italy, 2006; 498p, Available online: https://www.francoangeli.it/Ricerca/Scheda_libro.aspx?ID=13722 (accessed on 7 June 2018).

- Barnes, T.R.E.; Pant, A. Long-term course and outcome of schizophrenia. Psychiatry 2005, 4, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Frank, H.; Kalidindi, S.; Killaspy, H.; Glenn, R. Enabling Recovery: The Principles and Practice of Rehabilitation Psychiatry, 2nd ed.; BJPsych Bulletin: London, UK, 2016; Volume 40, p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- Bee, P.; Owen, P.; Baker, J.; Lovell, K. Systematic synthesis of barriers and facilitators to service user-led care planning. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 207, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needham, C.; Mary, Q.; Carr, S. Co-Production: An Emerging Evidence Base for Adult Social Care Transformation. Available online: https://lx.iriss.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/briefing31.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Thornicroft, G.; Tansella, M. The balanced care model for global mentalhealth. Psychol. Med. 2013, 43, 849–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Mental Health ATLAS 2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- WHO. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Martinelli, A.; Dal Corso, E.; Pozzan, T.; Cristofalo, D.; Bonetto, C.; Ruggeri, M. Addressing Challenges in Residential Facilities: Promoting Human Rights and Recovery While Pursuing Functional Autonomy. Psychiatr. Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, A.; Iozzino, L.; Ruggeri, M.; Marston, L.; Killaspy, H. Mental health supported accommodation services in England and in Italy: A comparison. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Veldhuizen, R.; Delespaul, P.; Kroon, H.; Mulder, N. FlexibleACT & Resource-group ACT: Different Working Procedures Which Can Supplement and Strengthen Each Other. A Response. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2015, 11, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munch Nielsen, C.; Hjorthøj, C.; Helbo, A.; Madsen, B.P.; Nordentoft, M.; Baandrup, L. Effectiveness of a multidisciplinary outreach intervention for individuals with severe mental illness in supported accommodation. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2025, 79, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, A.; Iozzino, L.; Pozzan, T.; Cristofalo, D.; Bonetto, C.; Ruggeri, M. Performance and effectiveness of step progressive care pathways within mental health supported accommodation services in Italy. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Placentino, A.; Lucchi, F.; Scarsato, G.; Fazzari, G.; Gruppo rex.it. La Mental Health Recovery Star: Caratteristiche e studio di validazione della versione italiana. Riv. Psichiatr. 2017, 52, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, C.; Williams, P.L.; Machingura, T.; Tse, S. A focus on recovery: Using the Mental Health Recovery Star as an outcome measure. Adv. Ment. Health 2015, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, G.; Weleminsky, J.; Onifade, Y.; Surgarman, P. Recovery Star: Validating user recovery. Psychiatrist 2012, 36, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, E.L. The Outcome Star: A Tool for Recovery Orientated Services. Exploring the Use of the Outcome Star in a Recovery Orientated Mental Health Service; Edith Cowan University: Joondalup, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Onifade, Y. The mental health recovery star. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2011, 15, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansella, M.; Amaddeo, F.; Burti, L.; Lasalvia, A.; Ruggeri, M. Evaluating a community-based mental health service focusing on severe mental illness. The Verona experience. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006, 113 (Suppl. S429), 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senato della Repubblica Legislatura XVII. Disegno di Legge. Disposizioni in Materia di Tutela della Salute Mentale Volte All’attuazione e allo Sviluppo dei Princìpi di cui alla Legge 13 Maggio 1978, n. 180. 2850 Italia. 2017. Available online: https://www.senato.it/export/ddl/full/48103?leg=17 (accessed on 7 July 2018).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5TM, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Available online: https://repository.poltekkes-kaltim.ac.id/657/1/Diagnostic%20and%20statistical%20manual%20of%20mental%20disorders%20_%20DSM-5%20(%20PDFDrive.com%20).pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Lora, A.; Bai, G.; Bianchi, S.; Bolongaro, G.; Civenti, G.; Erlicher, A.; Maresca, G.; Monzani, E.; Panetta, B.; Von Morgen, D.; et al. The italian version of HoNOS (Health of the Nation Outcome Scales), a scale for evaluating the outcome and the severity in mental health services. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2001, 10, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlicher, A.; Tansella, M. Health of the Nation Outcome Scales HoNOS: Una Scala per la Valutazione della Gravità e dell’esito nei Servizi di Salute Mentale; II Pensiero Scientifico Editore: Roma, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Amaddeo, F. Using large current databases to analyze mental health services. Epidemiol. Prev. 2018, 42, 98–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing Traditional Boundaries of Therapy; Dow Jones-Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition: DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, A.; Dal Corso, E.; Pozzan, T. Monitoring of the pathway of rehabilitation (MPR). J. Psychopathol. 2024, 30, 174–177. [Google Scholar]

- Martinelli, A.; Pozzan, T.; Corso, E.D.; Procura, E.; D’Astore, C.; Cristofalo, D.; Ruggeri, M.; Bonetto, C. Proprietà psicometriche della Scheda di Monitoraggio del Percorso Riabilitativo (MPR). Riv Psichiatr. 2022, 57, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, M.; Loftus, L.; Thornicroft, G. The Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN); RC of Psychiatrists: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri, M.; Lasalvia, A.; Nicolaou, S.; Tansella, M. The Italian version of the Camberwell assessment of need (CAN), an interview for the identification of needs of care. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 1999, 8, 135–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grammenos, S. Comparability of Statistical Data on Persons with Disabilities Across the EU. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2024/754219/IPOL_STU(2024)754219_EN.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Barnes, S.; Carson, J.; Gournay, K. Enhanced supported living for people with severe and persistent mental health problems: A qualitative investigation. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e4293–e4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killaspy, H.; Priebe, S.; McPherson, P.; Zenasni, Z.; Greenberg, L.; McCrone, P.; Dowling, S.; Harrison, I.; Krotofil, J.; Dalton-Locke, C.; et al. Predictors of moving on from mental health supported accommodation in England: National cohort study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 216, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killaspy, H.; Priebe, S.; McPherson, P.; Zenasni, Z.; McCrone, P.; Dowling, S.; Harrison, I.; Krotofil, J.; Dalton-Locke, C.; McGranahan, R.; et al. Feasibility randomised trial comparing two forms of mental health supported accommodation (Supported Housing and Floating Outreach); a component of the QUEST (Quality and Effectiveness of Supported Tenancies) study. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Eck, R.M.; Jelsma, A.; Blondeel, J.; Burger, T.J.; Vellinga, A.; de Koning, M.B.; Schirmbeck, F.; Kikkert, M.; Boyette, L.-L.; de Haan, L. The Association Between Change in Symptom Severity and Personal Recovery in Patients with Severe Mental Illness. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2025, 213, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Private Accommodation (N = 14) | Supported Accommodation (N = 11) | Total (N = 25) | * p-Value t Test or Fisher’s Exact Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 40.2 (10.6) | 42.3 (9.4) | 41.1 (9.9) | 0.617 |

| Marital status Single Partnered | 10 (71.4%) 4 (28.6%) | 9 (81.8%) 2 (18.2%) | 19 (76.0%) 6 (24.0%) | 0.452 |

| Educational achievement Lower education (primary/middle school only) Higher education (high school/further education) | 8 (57.1%) 6 (42.9%) | 5 (45.5%) 6 (54.5%) | 13 (52.0%) 12 (48.0%) | 0.430 |

| Work Employed Unemployed | 6 (42.9%) 8 (57.1%) | 5 (45.5%) 6 (54.5%) | 11 (44.0%) 14 (56.0%) | 0.607 |

| Primary clinical diagnosis Schizophrenia spectrum disorders Others | 8 (57.1%) 6 (42.9%) | 9 (81.8%) 2 (18.2%) | 17 (68.0%) 8 (32.0%) | 0.190 |

| Years old at first contact with psychiatric service, mean (SD) | 25.2 (10.4) | 25.1 (6.6) | 25.2 (8.8) | 0.973 |

| Number of acute ward admissions lifetime, mean (SD) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | - |

| Number of psychotropic drugs, mean (SD) | 2.5 (1.2) | 3.9 (2.6) | 3.1 (2.0) | 0.084 |

| Physical comorbidity (e.g., dyslipidemia, hypothyroidism), mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.694 |

| Substance misuse or gambling problem, mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.2) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.257 |

| Rating scale assessments | ||||

| MHRS, mean (SD) Physical and mental health Managing mental health Self-care Addictive behavior Activities and functioning Living skills Work Responsibilities Self-image Identity and self-esteem Trust and hope Networks Social networks Relationships | 6.6 (1.3) 7.2 (1.1) 6.1 (1.7) 7.3 (1.9) 8.1 (2.8) 7.0 (1.8) 6.3 (2.2) 6.1 (4.7) 8.6 (7.3) 6.4 (1.6) 6.3 (1.5) 6.5 (1.9) 5.6 (1.9) 5.6 (1.9) 5.6 (2.4) | 5.6 (1.7) 5.8 (2.0) 5.6 (1.9) 6.3 (2.8) 5.5 (3.5) 5.8 (1.7) 5.6 (1.8) 4.7 (2.4) 7.3 (2.6) 5.5 (1.8) 5.5 (2.1) 5.6 (1.6) 5.0 (2.0) 4.9 (2.1) 5.1 (2.8) | 6.2 (1.5) 6.6 (1.7) 5.9 (1.8) 6.8 (2.3) 6.9 (3.3) 6.5 (1.8) 5.3 (2.2) 5.5 (2.6) 8.0 (2.2) 6.0 (1.7) 5.9 (1.8) 6.1 (1.8) 5.4 (1.9) 5.3 (2.3) 5.4 (2.6) | 0.078 0.039 0.485 0.292 0.049 0.107 0.367 0.176 0.129 0.199 0.261 0.200 0.416 0.430 0.604 |

| GAF, mean (SD) | 63.9 (11.2) | 52.1 (16.0) | 58.7 (14.5) | 0.040 |

| HoNOS, mean (SD) | 11.6 (4.6) | 13.9 (6.5) | 12.6 (5.5) | 0.303 |

| MPR, mean (SD) | 8.9 (1.7) | 8.3 (1.4) | 8.6 (1.6) | 0.328 |

| CAN patient, total needs, mean (SD) Total met needs Total unmet needs Ratio met/unmet needs | 8.4 (4.6) 5.8 (3.5) 2.6 (2.7) 2.2 | 12.1 (3.9) 9.4 (3.6) 2.7 (2.9) 3.5 | 10.0 (4.6) 7.4 (3.9) 2.6 (2.7) 2.8 | 0.041 0.021 0.891 - |

| CAN staff, total needs, mean (SD) Total met needs Total unmet needs Ratio met/unmet needs | 8.7 (4.1) 6.0 (3.1) 2.7 (2.9) 2.2 | 13.4 (3.7) 9.9 (3.3) 3.5 (2.5) 2.8 | 10.8 (4.5) 7.7 (3.7) 3.0 (2.7) 2.6 | 0.008 0.006 0.510 - |

| BL Private Accommodation (N = 14) | FU Private Accommodation (N = 14) | * p-Value Paired t-Test | BL Supported Accommodation (N = 11) | FU Supported Accommodation (N = 11) | p-Value Paired t-Test or Fisher’s Exact Test | p-Value Paired t-Test or Fisher’s Exact Test PA vs. SA at FU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics | |||||||

| Marital status Single Partnered | 10 (71.4%) 4 (28.6%) | 8 (57.1%) 6 (42.9%) | 1.000 | 9 (81.8%) 2 (18.2%) | 8 (72.7%) 3 (27.3%) | 0.055 | 0.352 |

| Work Employed Unemployed | 6 (42.9%) 8 (57.1%) | 8 (57.1%) 6 (42.9%) | 0.103 | 5 (45.5%) 6 (54.5%) | 6 (54.5%) 5 (45.5%) | 0.061 | 0.393 |

| Number of psychotropic drugs, mean (SD) | 2.4 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.0) | <0.001 | 4.1 (2.5) | 4.2 (2.5) | <0.001 | 0.035 |

| Substance misuse or gambling problem, mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.6) | 0.6 (0.7) | <0.001 | 1.1 (0.2) | 0.8 (1.3) | <0.001 | 0.666 |

| Rating scale assessments | |||||||

| MHRS, mean (SD) Physical and mental health Activities and functioning Self-image Networks | 6.6 (1.3) 7.2 (1.1) 7.0 (1.8) 6.4 (1.6) 5.6 (1.9) | 7.4 (1.2) 7.5 (1.2) 7.7 (1.6) 7.3 (1.6) 6.6 (2.0) | <0.001 0.011 <0.001 0.028 <0.001 | 5.6 (1.7) 5.8 (2.0) 5.8 (1.7) 5.5 (1.8) 5.0 (2.0) | 5.9 (1.3) 6.3 (1.5) 6.0 (1.3) 5.6 (1.7) 5.3 (1.9) | <0.001 0.174 <0.001 0.091 0.001 | 0.112 0.206 0.020 0.207 0.464 |

| GAF, mean (SD) | 66.9 (11.2) | 66.5 (13.1) | <0.001 | 52.1 (16.0) | 66.8 (10.5) | 0.054 | 0.218 |

| HoNOS, mean (SD) | 11.6 (4.6) | 8.9 (5.6) | <0.001 | 13.9 (6.5) | 10.6 (2.7) | 0.629 | 0.830 |

| MPR, mean (SD) | 8.9 (1.7) | 10.0 (1.3) | 0.041 | 8.3 (1.4) | 8.6 (1.5) | 0.005 | 0.282 |

| CAN patient, total needs, mean (SD) Total met needs Total unmet needs Ratio met/unmet needs | 8.4 (4.6) 5.8 (3.5) 2.6 (2.7) 2.2 | 6 (3.6) 5 (2.9) 1 (1.8) 5 | 0.023 0.064 0.003 | 12.1 (3.9) 9.4 (3.6) 2.7 (2.9) 3.5 | 11.8 (3.6) 9.9 (3.9) 1.9 (1.6) 5.2 | 0.003 0.008 0.306 | 0.011 0.009 0.581 - |

| CAN staff, total needs, mean (SD) Total met needs Total unmet needs Ratio met/unmet needs | 8.7 (4.1) 6.0 (3.1) 2.7 (2.9) 2.2 | 6.9 (4.0) 5.8 (2.9) 1.1 (2.0) 5.3 | 0.006 0.051 0.002 | 13.4 (3.7) 9.9 (3.3) 3.5 (2.5) 2.8 | 12.9 (4.0) 3.7 (1.1) 3.1 (1.8) 1.2 | 0.012 0.015 0.663 | 0.012 0.033 0.056 - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinelli, A.; Pozzan, T.; Cristofalo, D.; Bonetto, C.; D’Astore, C.; Procura, E.; Barbui, C.; Ruggeri, M. Differences in Personal Recovery Among Individuals with Severe Mental Disorders in Private and Supported Accommodations: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081173

Martinelli A, Pozzan T, Cristofalo D, Bonetto C, D’Astore C, Procura E, Barbui C, Ruggeri M. Differences in Personal Recovery Among Individuals with Severe Mental Disorders in Private and Supported Accommodations: An Exploratory Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(8):1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081173

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinelli, Alessandra, Tecla Pozzan, Doriana Cristofalo, Chiara Bonetto, Camilla D’Astore, Elena Procura, Corrado Barbui, and Mirella Ruggeri. 2025. "Differences in Personal Recovery Among Individuals with Severe Mental Disorders in Private and Supported Accommodations: An Exploratory Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 8: 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081173

APA StyleMartinelli, A., Pozzan, T., Cristofalo, D., Bonetto, C., D’Astore, C., Procura, E., Barbui, C., & Ruggeri, M. (2025). Differences in Personal Recovery Among Individuals with Severe Mental Disorders in Private and Supported Accommodations: An Exploratory Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(8), 1173. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22081173