What Is the Role of Industry-Based Intermediary Organisations in Supporting Workplace Mental Health in Australia? A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

- Bibliographic databases: A search of Medline, Embase, Scopus, and Business source premier, from 1 January 2010 to 1 December 2023, was undertaken, along with one on Google Scholar (first 200 citations). The search strategy for Medline was as follows (adapted for other databases):

- exp workplace/.

- exp mental health/.

- 1 AND 2.

- (advocacy or intermediar * or union or trade or profession * or mediator * or facilitat * or arbitrat *). tw.

- 3 AND 4.

- Limit 5 to (yr = “2010-current”).

- A Google search (first 200 results) was conducted to identify the relevant organi-sations and websites publishing content on the subject area. Next, each of the rel-evant websites’ homepage were manually searched for potentially relevant doc-uments (e.g., web pages, reports). Within this step, each website and the date on which each search was conducted were documented.

- A targeted website search was conducted, including industry intermediaries identified in the Google search (ii) above, along with a review of policy and guideline documents from intermediary websites and government bodies.

- Manual searches on the reference lists of previously identified documents were conducted.

- Relevant experts were consulted.

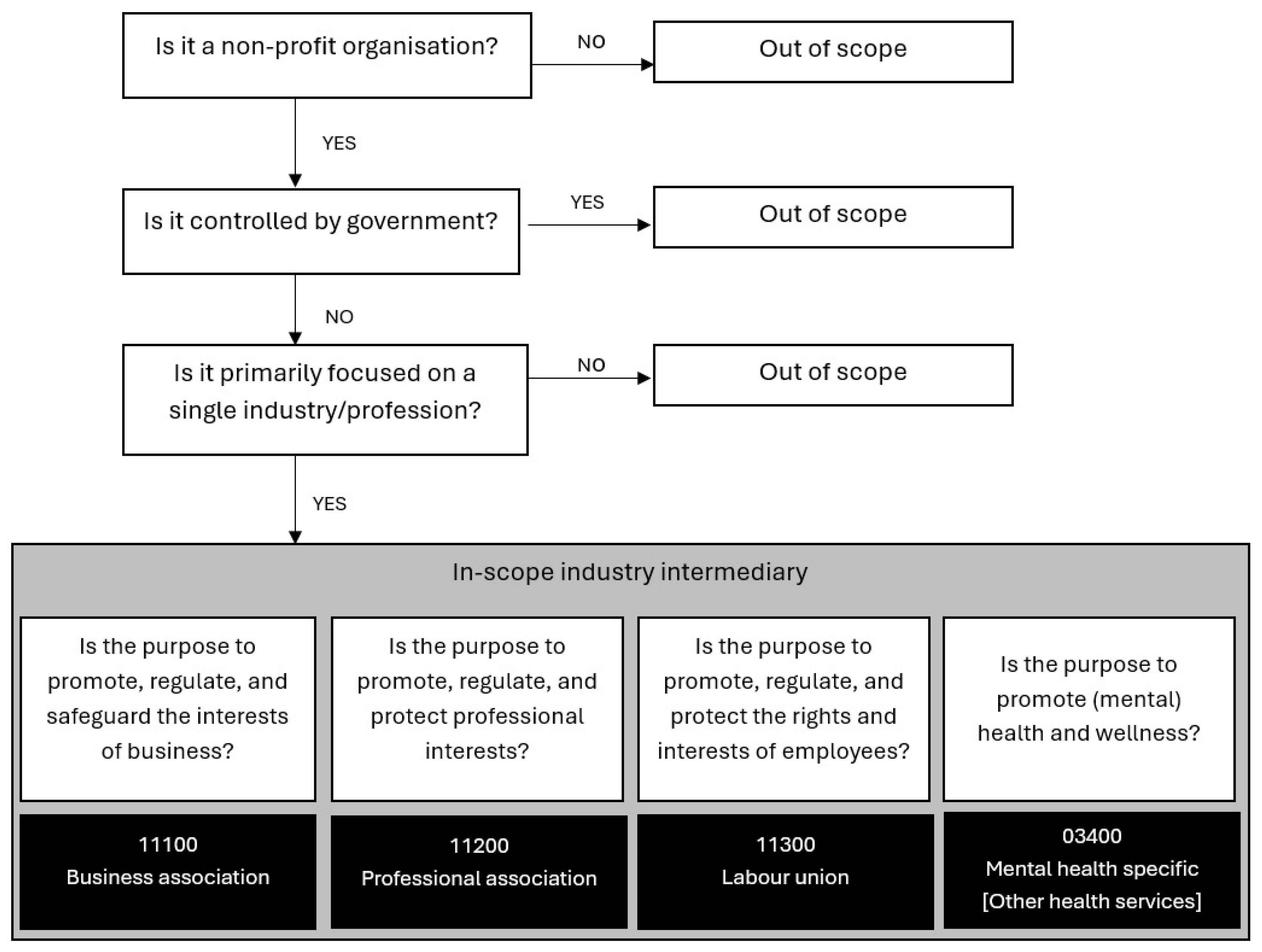

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Intermediary Classification

2.3. Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Classification of Organisations

3.2. Description of Programs

3.3. Intervention Types

Number of Interventions Offered by Intermediary Classification

3.4. Evaluation Activities

Proportion of Intermediaries with Published Evaluation of Their Mental Health Program, by Intermediary Classification

3.5. Evaluation Outcomes

3.5.1. Implementation Outcomes

3.5.2. Organisational Outcomes

3.5.3. Individual Outcomes

3.5.4. Other Evaluation Types

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barry, M.M.; Kuosmanen, T.; Keppler, T.; Dowling, K.; Harte, P. Priority actions for promoting population mental health and wellbeing. Ment. Health Prev. 2024, 33, 200312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Chick, R.; Kelloway, E.K. The three pillars of mental health in the workplace: Prevention, intervention and accommodation. In The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Wellbeing; SAGE: London, UK, 2021; pp. 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Mental Health at Work; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240053052 (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Scholl, J.C.; Okun, A.; Schulte, P.A. Workplace Safety and Health Information Dissemination, Sources, and Needs Among Trade Associations and Labor Organizations; Report Contract No.: 2017-166; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hasle, P.; Refslund, B. Intermediaries supporting occupational health and safety improvements in small businesses: Development of typology and discussion of consequences for preventive strategies. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2018, 62, S65–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okun, A.H.; Watkins, J.P.; Schulte, P.A. Trade associations and labor organizations as intermediaries for disseminating workplace safety and health information. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 60, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, K.W.; Levi-Faur, D.; Snidal, D. Theorizing regulatory intermediaries: The RIT model. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2017, 670, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, K.; Schroeder, E.; Fung, T.; Ellis, E.A.; Amin, J. Industry differences in psychological distress and distress-related productivity loss: A cross-sectional study of Australian workers. J. Occup. Health 2023, 65, e12428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugulies, R.; Aust, B.; Greiner, B.A.; Arensman, E.; Kawakami, N.; LaMontagne, A.D.; Madsen, I.E.H. Work-related causes of mental health conditions and interventions for their improvement in workplaces. Lancet 2023, 402, 1368–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safe Work Australia. Australian Work Health and Safety (WHS) Strategy 2023–2033; Safe Work Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2023. Available online: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-06/australian_whs_strategy_2022-32_june2024.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Satellite Account on Non-Profit and Related Institutions and Volunteer Work; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/docs/UN_TSE_HB_FNL_web.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, C.; Oxford, S.; McMillan, J. Evaluation of the Vicarious Trauma Prevention and Awareness Toolkit: Final Evaluation; Monash University: Melbourne, Australia, 2022; Available online: http://vtpat.org.au/storage/docs/evaluation-20.11.2022.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Australian Manufacturing Workers Union. Workplace Wellbeing. Available online: https://www.amwu.org.au/workwell_resources (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Western Australian Prison Officers’ Union. Stand TALR. Available online: http://standtalr.org (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Victorian Automotive Chamber of Commerce. Fine Tuning Automotive Mental Health. Available online: https://www.vaccsdc.com.au/projects/fine-tuning-automotive-mental-health-project/ (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Water Services Association of Australia. Water Industry Mental Health Framework. Available online: https://www.wsaa.asn.au/ (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Williams, K.; Fildes, D. Evaluation of the Trusted Advocates Network Trial (Farmers’ Trial) and the Seafood Industry Mental Health Supports Trial (Fishers’ Trial): Final Report; Centre for Health Service Development, Australian Health Services Research Institute, University of Wollongong: Wollongong, Australia, 2021; Available online: https://documents.uow.edu.au/content/groups/public/@web/@chsd/documents/doc/uow272115.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Housing Industry Association. Mental Health Program. Available online: http://hia.com.au/hia-community/what-we-do/mental-health-program (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Australian Football League. AFL Industry Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2020–2022. Available online: https://www.afl.com.au/mental-health-wellbeing/strategy (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Consult Australia. Mental Health Knowledge Hub. Available online: https://www.consultaustralia.com.au/home/business-services/mental-health-knowledge-hub (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Australian Resources and Energy Employer Association. Workforce Mental Health Framework; AREEA: Melbourne, Australia, 2021; Available online: https://www.areea.com.au/framework/#mentalhealthframework (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Grain Producers Australia. Farmer Mates Mental Health. Available online: https://www.grainproducers.com.au/farmer-mates-mental-health (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Australian Hotels Association (SA). Check Inn—Mental Health and Wellbeing. Available online: https://www.ahasa.com.au/latest-news/mental-health-and-wellbeing-program (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Civil Contractors Federation Victoria. Positive Plans Positive Futures. Available online: https://www.ccfvic.com.au/positive-plans-positive-futures/ (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Chartered Accountants, AUS./N.Z. CA Wellbeing: Chartered Accountants Aus/NZ, 2024. [Updated 11 October 2023]. Available online: https://www.charteredaccountantsanz.com/member-services/mentoring-and-support/ca-wellbeing (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Association of Consulting Architects Australia. Knowledge Hub: Mental Wellbeing. Available online: https://aca.org.au/knowledge-hub/other-key-issues/mental-wellbeing/ (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Australian Institute of Architects. Practice Notes: Mental Health. [Updated 20.11.2019]. Available online: https://acumen.architecture.com.au/practice/human-resources/mental-health-in-the-profession (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Australian and International Pilots Association. AIPA Welfare. Available online: https://www.aipa.org.au/welfare (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Australian Veterinary Association. Thrive 2022. Available online: https://www.ava.com.au/Thrive/ (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Superfriend. Wellbeing on Call: Final Report; Superfriend: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/workwell-mhif-wellbeing-call (accessed on 18 January 2024).

- Entertainment Assist. entertainmentassist.org.au. Available online: https://www.entertainmentassist.org.au (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Hiruy, K.; Elmes, A. Support Act—Service Use, Effects and Social Return on Investment Report 2022; Centre for Social Impact, Swinburne University of Technology: Hawthorn, Australia, 2022; Available online: https://supportact.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Support-Act-SROI-report-revised-Nov-2022-FINAL74.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Nursing and Midwifery Health Program Victoria. Nursing and Midwifery Health Program 2023. Available online: https://www.nmhp.org.au (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Minds Count Foundation. Mindscount. Available online: https://mindscount.org/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Mentally Healthy Change Group. mentally-healthy.org. Available online: https://www.mentally-healthy.org/ (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Drs4Drs: An Australian Medical Association Subsidiary. Drs4Drs [Updated 2023]. Available online: https://www.drs4drs.com.au/ (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- The Arts Wellbeing Collective. The Arts Wellbeing Collective. Available online: https://artswellbeingcollective.com.au/ (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Healthy Heads in Trucks and Sheds. Healthy Heads in Trucks and Sheds: Review. 2023. Available online: https://www.healthyheads.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/HHTS28530-HH_Annual_Review_2022-23_P11-1-1.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Gunn, K.M.; Skaczkowski, G.; Dollman, J.; Vincent, A.D.; Brumby, S.; Short, C.E.; Turnbull, D. A self-help online intervention is associated with reduced distress and improved mental wellbeing in Australian farmers: The evaluation and key mechanisms of www.ifarmwell.com.au. J. Agromed. 2023, 28, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SuperFriend. SuperFriend Annual Report 2022–2023; Superfriend: Melbourne, Australia, 2023; Available online: https://www.superfriend.com.au/about-us/governance-and-reports (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Ross, V.; Caton, N.; Gullestrup, J.; Kõlves, K. A longitudinal assessment of two suicide prevention training programs for the construction industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullestrup, J.; King, T.; Thomas, S.L.; LaMontagne, A.D. Effectiveness of the Australian MATES in construction suicide prevention program: A systematic review. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheen, H.; Taouk, Y.; Lamontagne, A.D.; Spittal, M.; King, T. Suicide trends among Australian construction workers during years 2001–2019. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayers, E.; Rich, J.; Rahman, M.M.; Kelly, B.; James, C. Does Help Seeking Behavior Change over Time following a Workplace Mental Health Intervention in the Coal Mining Industry? J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, E282–E290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynan, R.J.; James, C.; Considine, R.; Skehan, J.; Gullestrup, J.; Lewin, T.J.; Wiggers, J.; Kelly, B.J. Feasibility and acceptability of strategies to address mental health and mental ill-health in the Australian coal mining industry. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2018, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, V.; Caton, N.; Mathieu, S.; Gullestrup, J.; Kõlves, K. Evaluation of a suicide prevention program for the energy sector. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, N.; Guntuku, S. Mates in Manufacturing Suicide Awareness Pilot Program: Final Evaluation Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375765441_Mates_in_Manufacturing_Suicide_Awareness_Pilot_Program_Final_Evaluation_Report (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- King, K.E.; Liddle, S.K.; Nicholas, A. A qualitative analysis of self-reported suicide gatekeeper competencies and behaviour within the Australian construction industry. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2023, 35, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.; Slade, T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler psychological distress scale (K10). Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2001, 25, 494–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickwood, D.J.; Mazzer, K.R.; Telford, N.R.; Parker, A.G.; Tanti, C.J.; McGorry, P.D. Changes in psychological distress and psychosocial functioning in young people visiting headspace centres for mental health problems. Med. J. Aust. 2015, 202, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, T.R.; Tinc, P.J.; Guerin, R.J.; Schulte, P.A. Translation research in occupational health and safety settings: Common ground and future directions. J. Saf. Res. 2020, 74, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, T.R.; Sinclair, R. Application of a model for delivering occupational safety and health to smaller businesses: Case studies from the US. Saf. Sci. 2015, 71, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, W.J. Employee well-being outcomes from individual-level mental health interventions: Cross-sectional evidence from the United Kingdom. Ind. Relat. J. 2024, 55, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, M.K.; Hege, A.; Crizzle, A.M. An agenda for advancing research and prevention at the nexus of work organization, occupational stress, and mental health and well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMontagne, A.D.; Martin, A.; Page, K.M.; Reavley, N.J.; Noblet, A.J.; Milner, A.J.; Keegel, T.; Smith, P.M. Workplace mental health: Developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, K.E.; Johnson, S.T.; Berkman, L.F.; Sianoja, M.; Soh, Y.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Kelly, E.L. Organisational- and group-level workplace interventions and their effect on multiple domains of worker well-being: A systematic review. Work. Stress 2021, 36, 30–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzel, R.Z.; Roemer, E.C.; Holingue, C.; Fallin, M.D.; McCleary, K.; Eaton, W.; Agnew, J.; Azocar, F.; Ballard, D.P.; Bartlett, J.; et al. Mental health in the workplace: A call to action proceedings from the mental health in the workplace—Public health summit. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 60, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Mental Wellbeing at Work. NICE Guideline [NG212]; NICE UK: Manchester, UK, 2022; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng212 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Tyler, S.; Hunkin, H.; Pusey, K.; Gunn, K.; Clifford, B.; McIntyre, H.; Procter, N. Disentangling rates, risk, and drivers of suicide in the construction industry: A systematic review. Crisis J. Crisis Interv. Suicide Prev. 2022, 45, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.J.; Smart, P.; Huff, A.S. Shades of grey: Guidelines for working with the grey literature in systematic reviews for management and organizational studies. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 432–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez, A. Grey literature: An important resource in systematic reviews. J. Evid. Based Med. 2017, 10, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Program | Author, Year | Intermediary Type a | Intervention Type (s): WHO Recommended b | Evaluated Y/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vicarious trauma prevention and awareness toolkit Available online: http://vtpat.org.au/ (accessed on 18 January 2024) | Schroder [15] 2022 | U | OU, OMH | Y |

| Collaboration delivers wellbeing: Australian Manufacturing Workers Union Collaboration Available online: https://www.amwu.org.au/workwell_resources (accessed on 17 January 2024). | Australian Manufacturing Workers Union [16] | U | OU, MT, WT, IPSD | N |

| Stand TALR. WA Prison Officers Union Available online: https://standtalr.org/ (accessed on 15 January 2024). | Western Australian Prison Officers’ Union [17] | U | WT | N |

| Fine Tuning Automotive Mental Health Available online: https://www.vaccsdc.com.au/projects/fine-tuning-automotive-mental-health-project/ (accessed on 16 January 2024). | Victorian Automotive Chamber of Commerce [18] | BA | OU | Y |

| Water Industry Mental Health Framework Available online: https://www.wsaa.asn.au/ (accessed on 24 January 2024). | Water Services Association of Australia [19] | BA | OU | N |

| Stay Afloat Available online: https://www.stayafloat.com.au (accessed on 15 January 2024). | Williams and Fildes [20] 2021 | BA | OU, IPSD, O | Y |

| Building Mentally Healthy Environments: HIA Workplace toolkit Available online: https://hia.com.au/hia-community/what-we-do/mental-health-program (accessed on 22 January 2024). | Housing Industry Association [21] | BA | MT, WT, O | N |

| AFL Industry Mental Health & Wellbeing Strategy Available online: https://www.afl.com.au/mental-health-wellbeing/strategy (accessed on 15 January 2024). | Australian Football League [22] | BA | OU, O | N |

| Consult Australia: Striving for mentally healthy workplaces Available online: https://www.consultaustralia.com.au/home/business-services/mental-health-knowledge-hub (accessed on 21 January 2024). | Consult Australia [23] | BA | OU, O | N |

| Resources and energy industry: Workforce mental health framework Available online: https://www.areea.com.au/framework (accessed on 15 January 2024). | Australian Resources and Energy Employer Association [24], 2021 | BA | OU, OMH, MT, WT, O | N |

| Grain Producers Australia: Farmer Mates Mental Health Available online: https://www.grainproducers.com.au/farmer-mates-mental-health (accessed on 26 January 2024). | Grain Producers Australia [25] | BA | O | N |

| Australian Retailers Association: Mental wellbeing Available online: https://www.retail.org.au/mental-wellbeing (accessed on 21 January 2024). | Australian Hotels Association (SA) [26] | BA | O | N |

| Australian Hotels Association South Australia: Check Inn Available online: https://www.ahasa.com.au/latest-news/mental-health-and-wellbeing-program (accessed on 30 January 2024). | Australian Hotels Association (SA) [26] | BA | IUPS | N |

| Civil Contractors Federation: Positive Plans Positive Futures Available online: https://www.ccfvic.com.au/positive-plans-positive-futures (accessed on 20 January 2024). | Civil Contractors Federation Victoria [27] | BA | OU | Y |

| Chartered Accountants Wellbeing Available online: https://www.charteredaccountantsanz.com/member-services/mentoring-and-support/ca-wellbeing (accessed on 15 January 2024). | Chartered Accountants Aus/NZ [28] 2024 | PA | IPSD, O | N |

| Association of Consulting Architects: Wellbeing Available online: https://aca.org.au/knowledge-hub/other-key-issues/mental-wellbeing (accessed on 17 January 2024). | Association of Consulting Architects Australia [29] | PA | OU, MT, ISPD, O | N |

| Australian Institute of Architects: Mental Health Practice Notes Available online: https://acumen.architecture.com.au/practice/human-resources/mental-health-in-the-profession (accessed on 20 January 2024). | Australian Institue of Architects [30] | PA | O | N |

| Australian & International Pilots Association: Pilot Welfare program Available online: https://aipa.org.au/welfare (accessed on 21 January 2024). | Australian and International Pilots Association [31] | PA | IPSD, O | N |

| Thrive: Veterinary industry wellness program Available online: https://www.ava.com.au/Thrive/ (accessed on 18 January 2024). | Australian Veterinary Association [32], 2022 | PA | OU, MT, WT, IPSD, O | N |

| Wellbeing On Call: Thriving Contact Centres Previously at: https://wellbeingoncall.superfriend.com.au (accessed on 18 January 2024). | Superfriend [33], 2020 | MHS | OU, OMH, MT, WT, IUPS, IUPA | Y |

| Entertainment Assist Available online: https://www.entertainmentassist.org.au (accessed on 16 January 2024). | Entertainment Assist [34] | MHS | WT, O | N |

| Support Act Available online: https://supportact.org.au (accessed on 21 January 2024). | Hiruy [35], 2022 | MHS | OU, MT, WT, IPSD | Y |

| Nursing and Midwifery Health Program Available online: https://www.nmhp.org.au (accessed on 10 January 2024). | Nursing and Midwifery Health Program Victoria [36], 2023 | MHS | MT, IPSD | N |

| Minds Count Available online: https://mindscount.org (accessed on 22 January 2024). | Minds Count Foundation [37] | MHS | OU, O | N |

| Mentally healthy minimum standards for the creative, media and marketing industry Available online: https://www.mentally-healthy.org (accessed on 17 January 2024). | Mentally Healthy Change Group [38] | MHS | OU, O | N |

| Drs4Drs Available online: https://www.drs4drs.com.au (accessed on 19 January 2024). | Drs4Drs: An Australian Medical Association subsidiary [39] | MHS | IPSD, O | N |

| Arts Wellbeing Collective Available online: https://artswellbeingcollective.com.au (accessed on 20 January 2024). | The Arts Wellbeing Collective [40] | MHS | OU, MT, WT, IPSD, O | N |

| Healthy Heads in Trucks and Sheds Available online: https://www.healthyheads.org.au (accessed on 24 January 2024). | Healthy Heads in Trucks and Sheds [41] 2023 | MHS | OU, MT, WT, IUPS, IUPA, IPSD, IPAD | Y |

| Ifarmwell Available online: https://ifarmwell.com.au (accessed on 24 January 2024). | Gunn, Skaczkowski [42] †, 2023 | MHS | IUPS, IPSD | Y |

| Superfriend Available online: https://www.superfriend.com.au (accessed on 10 January 2024). | SuperFriend [43], 2023 | MHS | OU, MT, WT, IUPS, O | Y |

| MATES in construction * Available online: https://www.mates.org.au/construction/ (accessed on 10 January 2024). | Ross et al. 2020 [44] † Gullestrup et al. 2023 [45] †, Maheen et al. 2022 [46] † | MHS | WT | Y |

| MATES in mining * Available online: https://www.mates.org.au/mining/ (accessed on 10 January 2024). | Sayers et al., 2019 [47] † Tynan et al., 2018 [48] † | MHS | WT | Y |

| MATES in energy * Available online: https://www.mates.org.au/energy/ (accessed on 10 January 2024). | Ross et al., 2020 [49] † | MHS | MT, WT | Y |

| MATES in manufacturing trial * Available online: https://www.amwu.org.au/mates_in_manufacturing (accessed on 15 January 2024). | Hall and Guntuku [50] 2023 | MHS | WT | Y |

| Incolink Wellbeing & Support + BlueHats Available online: https://incolink.org.au/wellbeing-support-services (accessed on 19 January 2024). | King et al., [51] † 2023 | Other | OU, WT, MT, IPSD | Y |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burns, K.; Ellis, L.A.; De Almeida Neto, A.; Lopes, C.V.A.; Amin, J. What Is the Role of Industry-Based Intermediary Organisations in Supporting Workplace Mental Health in Australia? A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070974

Burns K, Ellis LA, De Almeida Neto A, Lopes CVA, Amin J. What Is the Role of Industry-Based Intermediary Organisations in Supporting Workplace Mental Health in Australia? A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):974. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070974

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurns, Kristy, Louise A. Ellis, Abilio De Almeida Neto, Carla Vanessa Alves Lopes, and Janaki Amin. 2025. "What Is the Role of Industry-Based Intermediary Organisations in Supporting Workplace Mental Health in Australia? A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070974

APA StyleBurns, K., Ellis, L. A., De Almeida Neto, A., Lopes, C. V. A., & Amin, J. (2025). What Is the Role of Industry-Based Intermediary Organisations in Supporting Workplace Mental Health in Australia? A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22070974