Breast Cancer Survivors’ Perception on Health Promotion and Healthy Lifestyle: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis

Abstract

1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Protocol Registration

2.3. Formulation of the Research Question

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Eligibility Criteria

2.6. Data Selection and Extraction

2.7. The Methodological Quality of Studies

2.8. Data Analysis and Synthesis

3. Results

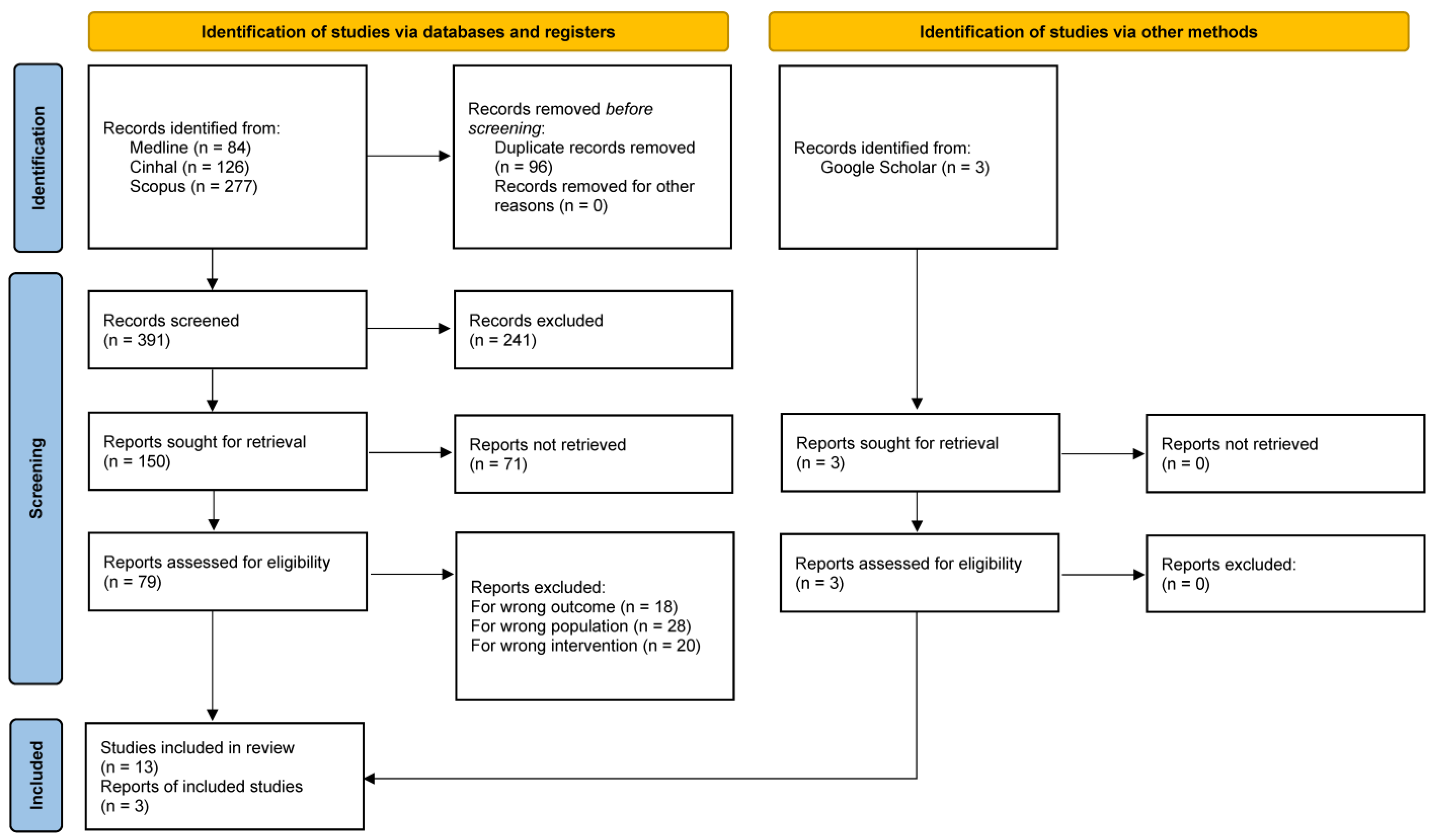

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

3.2.1. Theme I: Challenges

3.2.2. Theme II: Self-Motivation and Empowerment

3.2.3. Theme III: Relationships as a Facilitator

3.2.4. Theme IV: Barriers to Change

3.2.5. Theme V: Proactive Support Strategies

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

4.2. Clinical and Public Health Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Breast Cancer. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Afkar, A.; Jalilian, H.; Pourreza, A.; Mir, H.; Sigaroudi, A.E.; Heydari, S. Cost analysis of breast cancer: A comparison between private and public hospitals in Iran. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T.; Seidman, A.; Li, Q.; Seluzicki, C.; Blinder, V.; Meghani, S.H.; Farrar, J.T.; Mao, J.J. Living with chronic pain: Perceptions of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 169, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, E.E.; Kennedy, C.W.; Gluch, L.; Carmalt, H.L.; Janu, N.C.; Joseph, M.G.; Donellan, M.J.; Molland, J.G.; Gillett, D.J. Patterns of breast cancer relapse. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 32, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moloney, N.A.; Pocovi, N.C.; Dylke, E.S.; Graham, P.L.; De Groef, A. Psychological factors are associated with pain at all time frames after breast cancer surgery: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 915–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, P.; Suwankhong, D. Living with breast cancer: The experiences and meaning-making among women in Southern Thailand. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2016, 25, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Division of Cancer Control & Population Sciences. 2025. Available online: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/definitions (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Morgan, E.; O’Neill, C.; Shah, R.; Langselius, O.; Su, Y.; Frick, C.; Fink, H.; Bardot, A.; Walsh, P.M.; Woods, R.R.; et al. Metastatic recurrence in women diagnosed with non-metastatic breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. 2024, 26, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinsma, T.J.; Dyer, A.M.; Rogers, C.J.; Schmitz, K.H.; Sturgeon, K.M. Effects of diet and exercise-induced weight loss on biomarkers of inflammation in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2021, 30, 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.L.; Thomson, C.; Gansler, T.; Gapstur, S.M.; McCullough, M.L.; Patel, A.V.; Andrews, K.S.; Bandera, E.V.; Spees, C.K.; Robien, K.; et al. American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagalaz-Anula, N.; Mora-Rubio, M.J.; Obrero-Gaitán, E.; Del-Pino-Casado, R. Recreational physical activity reduces breast cancer recurrence in female survivors of breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 59, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrino, F. Mediterranean Diet and Its Association with Reduced Invasive Breast Cancer Risk. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 535–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNysschen, C.; Brown, J.K.; Baker, M.; Wilding, G.; Tatewsky, S.; Cho, M.H.; Dodd, M.J. Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors of Breast Cancer Survivors. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2015, 24, 504–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch-Shimon, S.; Cardoso, F.; Partridge, A.H.; Abulkhair, O.; Azim Jr, H.A.; Bianchi-Micheli, G.; Cardoso, M.J.; Curigliano, G.; Gelmon, K.A.; Harbeck, N.; et al. ESO–ESMO 4th international consensus guidelines for breast cancer in young women (BCY4). Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 674–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Shi, A.; Lu, C.; Song, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J. Breast Cancer: Epidemiology and Etiology. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 72, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarini, A.; Villarini, M.; Gargano, G.; Moretti, M.; Berrino, F. DianaWeb: Un progetto dimostrativo per migliorare la prognosi in donne con carcinoma mammario attraverso gli stili di vita. Epidemiol. Prev. 2015, 9, 402–405. [Google Scholar]

- Pudkasam, S.; Polman, R.; Pitcher, M.; Fisher, M.; Chinlumprasert, N.; Stojanovska, L.; Apostolopoulos, V. Physical activity and breast cancer survivors: Importance of adherence, motivational interviewing and psychological health. Maturitas 2018, 116, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Cai, H.; Gu, K.; Shi, L.; Yu, D.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, Y.; Bao, P.; Shu, X.O. Adherence to Dietary Recommendations among Long-Term Breast Cancer Survivors and Cancer Outcome Associations. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2020, 29, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCRF/AICR. Research and Policy | World Cancer Research Fund. 2018. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/research-policy/ (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Koutoukidis, D.; Lopes, S.; Fisher, A.; Williams, K.; Croker, H.; Beeken, R.J. Lifestyle advice to cancer survivors a qualitative study on the perspectives of health professionals. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yufe, S.J.; Fergus, K.D.; Male, D.A. Lifestyle change experiences among breast cancer survivors participating ina pilot intervention A narrative thematic analysis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 41, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çömez, S.; Karayurt, O. We as Spouses Have Experienced a Real Disaster! A Qualitative Study of Women with Breast Cancer and Their Spouses. Cancer Nurs. 2016, 39, E19–E28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma, M.L.; Blomqvist, L.; Blomqvist, C.; Nikander, R.; Gustavsson-Lilius, M.; Saarto, T. Experiences of Breast Cancer Survivors Participating in a Tailored Exercise Intervention: A Qualitative Study. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Jirojwong, S.; Johnson, M.; Welch, A. Research Methods in Nursing and Midwifery: Pathways to Evidence Based Practice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Finfgeld, D.L. Metasynthesis: The state of the art—So far. Qual. Health Res. 2003, 13, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schiavo, J.H. PROSPERO: An International Register of Systematic Review Protocols. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2019, 38, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER Tool for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, D. Handsearching still a valuable element of the systematic review. Evid. Based Dent. 2008, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Egan, M.; Lorenc, T.; Bond, L.; Popham, F.; Fenton, C.; Benzeval, M. Considering methodological options for reviews of theory: Illustrated by a review of theories linking income and health. Syst. Rev. 2014, 3, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.; Field, J. JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mays, N.; Pope, C.; Popay, J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2005, 10 (Suppl. 1), 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Sit, J.W.H.; Cheng, K.K.F. A qualitative insight into self-management experience among Chinese breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosevic, E.; Brunet, J.; Campbell, L.K. Exploring tensions within young breast cancer survivors’ physical activity, nutrition and weight management beliefs and practices. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.Y.; Lee, K.T. From Patient to Survivor: Women’s Experience With Breast Cancer After 5 Years. Cancer Nurs. 2016, 39, E40–E48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coro, D.G.; Hutchinson, A.; Banks, S.; Coates, A.M. Diet and cognitive function in cancer survivors with cancer-related cognitive impairment A qualitative study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, 29, e13303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckenstein, H.; Slim, M.; Kim, H.; Plourde, H.; Kilgour, R.; Cohen, T. Acceptability of a structured diet and exercise weight loss intervention in breast cancer survivors living with an overweight condition or obesity: A qualitative analysis. Cancer Rep. 2021, 4, e1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschey, R.; Docherty, L.S.; Pan, W.; Lipkus, I. Exploration of Exercise Outcome Expectations among Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2017, 176, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunet, J.; Taran, S.; Burke, S.; Sabiston, C.M. A qualitative exploration of barriers and motivators to physical activity participation in women treated for breast cancer. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 2038–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Han, J.; Jang Kyeong, M.; Lee Young, M. The experience of cancer-related fatigue, exercise and exercise adherence among women breast cancer survivors Insights from focus group interviews. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deery, E.; Johnston, K.; Butler, T. ‘It’s like being pushed into sea on a boat with no oars’: Breast cancer survivorship and rehabilitation support in Ireland and the UK. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 36, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajoei, R.; Azadeh, P.; ZohariAnboohi, S.; Ilkhani, M.; Nabavi, F.H. Breast cancer survivorship needs: A qualitative study. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumdaeng, S.; Sethabouppha, H.; Chontawan, R.; Soivong, P. Health Behavior Changes among Survivors of Breast Cancer after Treatment Completion. Pac. Rim Int. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 24, 472–484. [Google Scholar]

- Drageset, S.; Lindstrøm, T.C.; Underlid, K. “I just have to move on”: Women’s coping experiences and reflections following their first year after primary breast cancer surgery. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 21, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengün İnan, F.; Üstün, B. Fear of Recurrence in Turkish Breast Cancer Survivors: A Qualitative Study. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2019, 30, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Park, S.; Kim, S.J.; Hur, M.H.; Lee, B.G.; Han, M.S. Self-management Needs of Breast Cancer Survivors After Treatment: Results From a Focus Group Interview. Cancer Nurs. 2020, 43, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arem, H.; Duarte, D.A.; White, B.; Vinson, K.; Hinds, P.; Ball, N.; Dennis, K.; McCready, D.M.; Cafferty, L.A.; Berg, C.J. Young Adult Cancer Survivors’ Perspectives on Cancer’s Impact on Different Life Areas Post-Treatment: A Qualitative Study. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2024, 13, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabi, E.; Hajian, S.; Simbar, M.; Hoshyari, M.; Zayeri, F. The Lived Experience of Iranian Women Confronting Breast Cancer Diagnosis. J. Caring Sci. 2016, 5, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaelson, V.; Pilato, K.A.; Davison, C.M. Family as a health promotion setting: A scoping review of conceptual models of the health-promoting family. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Taylor, R.A.; Rocque, G.B.; Azuero, A.; Acemgil, A.; Martin, M.Y.; Astin, M.; Ejem, D.; Kvale, E.; et al. The self-care practices of family caregivers of persons with poor prognosis cancer: Differences by varying levels of caregiver well-being and preparedness. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 2437–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, B.I.; Lippman, M.E. Comment on “The lingering mysteries of metastatic recurrence in breast cancer”. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 484–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, J.; Thomas, R.; Howell, D.; Dubouloz Wilner, C.J. Empowering Cancer Survivors in Managing Their Own Health: A Paradoxical Dynamic Process of Taking and Letting Go of Control. Qual. Health Res. 2023, 33, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shengyao, Y.; Salarzadeh Jenatabadi, H.; Mengshi, Y.; Minqin, C.; Xuefen, L.; Mustafa, Z. Academic resilience, self-efficacy, and motivation: The role of parenting style. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudkasam, S.; Feehan, J.; Talevski, J.; Vingrys, K.; Polman, R.; Chinlumprasert, N.; Stojanovska, L.; Apostolopoulos, V. Motivational strategies to improve adherence to physical activity in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2021, 152, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.F.; Cruz, A.; Moreira, C.; Santos, M.C.; Silva, T. Social Support Provided to Women Undergoing Breast Cancer Treatment: A Study Review. Adv. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 3, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, N.L.; Owusu, C.; Flocke, S.; Krejci, S.A.; Kullman, E.L.; Austin, K.; Bennett, B.; Cerne, S.; Harmon, C.; Moore, H.; et al. A community-based exercise and support group program improves quality of life in African-American breast cancer survivors: A quantitative and qualitative analysis. Int. J. Sports Exerc Med. 2015, 1, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Duberstein, P.R. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2010, 75, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.H.; Yoo, S.H.; Sung, J.H.; Oh, E.G.; Kim, N.; Lee, J. Digital health interventions for adult patients with cancer evaluated in randomized controlled trials: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e38333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golani, R.; Kagenaar, E.; Jégu, J.; Belot, A.; Ling, S. Socio-economic inequalities in second primary cancer incidence: A competing risks analysis of women with breast cancer in England between 2000 and 2018. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 156, 2283–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Maaren, M.C.; Rachet, B.; Sonke, G.S.; Mauguen, A.; Rondeau, V.; Siesling, S.; Belot, A. Socioeconomic status and its relation with breast cancer recurrence and survival in young women in the Netherlands. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022, 77, 102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opia, F.N.; Igboekulie, C.V.; Matthew, K.A. Socioeconomic Disparities in Breast Cancer Care: Addressing Global Challenges in Oncology Outcomes. Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. Res. 2025, 14, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pontillo, M.; Trio, R.; Rocco, N.; Cinquerrui, A.; Di Lorenzo, M.; Catanuto, G.; Magnoni, F.; Calenda, F.; Castiello, C.L.; Ingenito, M.; et al. Dietary Interventions for Breast Cancer Prevention: Exploring the Role of Nutrition in Primary and Tertiary Prevention Strategies. Healthcare 2025, 13, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcik, K.M.; Wilson, O.W.; Shiels, M.S.; Sheppard, V.B.; Jayasekera, J. Racial, Ethnic, and Socioeconomic Disparities in Meeting Physical Activity Guidelines among Female Breast Cancer Survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2024, 33, 1610–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneu, A.; Lavoué, V.; Guillermet, S.; Levêque, J.; Mathelin, C.; Brousse, S. How could physical activity decrease the risk of breast cancer development and recurrence? Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. Senol. 2024, 52, 158–164. [Google Scholar]

- Wojcik, K.M.; Kamil, D.; Zhang, J.; Wilson, O.W.A.; Smith, L.; Butera, G.; Isaacs, C.; Kurian, A.; Jayasekera, J. A scoping review of web-based, interactive, personalized decision-making tools available to support breast cancer treatment and survivorship care. J. Cancer Surviv. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallowfield, L.; Starkings, R.; Palmieri, C.; Tait, A.; Stephen, L.; May, S.; Habibi, R.; Russ, S.; Shilling, V.; Jenkins, V.; et al. Living with metastatic breast cancer (LIMBER): Experiences, quality of life, gaps in information, care and support of patients in the UK. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, B.; Stump, T.; Penedo, F.; Pfammatter, A.F.; Robinson, J.K. Toward a health-promoting system for cancer survivors: Patient and provider multiple behavior change. Health Psychol. 2019, 38, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Leech, N.L. A Call for Qualitative Power Analyses. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Databases | Search Strings | Data | Number of Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEDLINE | ((((breast[Title/Abstract]) OR (chest[Title/Abstract]) OR (mammary glands[Title/Abstract]) OR (bosom[Title/Abstract])) AND ((cancer[Title/Abstract]) OR (tumor[Title/Abstract]) OR (carcinoma[Title/Abstract]) OR (malignancy[Title/Abstract]) OR (tumefaction[Title/Abstract]) OR (neoplasia[Title/Abstract]) OR (neoplasm[Title/Abstract]) OR (malignancies[Title/Abstract]) OR (malignant neoplasms[Title/Abstract])) AND ((survivor[Title/Abstract]) OR (recurrence[Title/Abstract]) OR (relapse[Title/Abstract]) OR (repetition[Title/Abstract]) OR (long-term survivor[Title/Abstract]) OR (long term survivor[Title/Abstract]) OR (survivor, long term[Title/Abstract]) OR (survivor, long-term[Title/Abstract])) AND ((risk factor*[Title/Abstract]) OR (diet[Title/Abstract]) OR (nutrition[Title/Abstract]) OR (physical activity[Title/Abstract]) OR (exercises[Title/Abstract]) OR (activity, physical[Title/Abstract]) OR (activities, physical[Title/Abstract]) OR (physical activities[Title/Abstract]) OR (physical exercise*[Title/Abstract]) OR (aerobic exercise[Title/Abstract]) OR (exercise, aerobic[Title/Abstract]) OR (exercise training*[Title/Abstract]) OR (obesity[Title/Abstract]) OR (overweight[Title/Abstract]) OR (lifestyle[Title/Abstract]) OR (quality of life[Title/Abstract]) OR (habits[Title/Abstract]) OR (weight management[Title/Abstract]) OR (weight loss[Title/Abstract]) OR (behaviour*[Title/Abstract]))) AND ((qualitative research[MeSH Terms]) OR (interviews as topic[MeSH Terms]) OR (focus group[MeSH Terms])))) | 29 November 2024 | n = 84 |

| CINHAL | AB (breast OR bosom OR mammary glands) AND AB (cancer OR tumor OR neoplasia OR neoplasm OR carcinoma OR tumefaction OR malignancies) AND AB (survivor* OR recurrence* OR survivorship) AND AB (lifestyle OR diet OR (risk AND factor*) OR nutrition OR physical AND activity OR exercise OR overweight OR obesity OR (weight AND management) OR (weight AND loss)) AND AB (qualitative) | 29 November 2024 | n = 126 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (breast OR bosom OR (mammary AND glands)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (cancer OR tumor OR neoplasia OR neoplasm OR carcinoma OR tumefaction OR malignancies) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (survivor* OR recurrence* OR survivorship) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (lifestyle OR diet OR (risk AND factor*) OR nutrition OR physical AND activity OR exercise OR overweight OR obesity OR (weight AND management) OR (weight AND loss)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (qualitative) | 29 November 2024 | n = 277 |

| Reference | Aim | Method/Study Design | Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheng et al., 2017 [35] | To explore the self-management experiences of Chinese BCSs. | Qualitative study utilizing secondary analysis of interview data; 19 participants with diagnosis in the last 5 years. | Identified themes include managing health and well-being, managing emotions, managing roles and relationships, and cultural influences on self-management. | Chinese BCSs actively engage in self-management practices influenced by cultural beliefs, highlighting the need for tailored interventions. |

| Milosevic et al., 2020 [36] | To investigate the attitudes and behaviors of young breast cancer survivors concerning physical activity, nutrition, and weight management. | Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with 12 young BCSs. | Recognized conflicts between awareness of health benefits and the practical obstacles to achieving them; themes included sustaining a healthy lifestyle, navigating social expectations, and balancing personal and medical priorities. | Young BCSs face unique challenges in maintaining health-promoting behaviors, underscoring the need for tailored interventions addressing individual and contextual barriers. |

| Fang and Lee, 2016 [37] | To explore the experiences and needs of women BCSs, with a focus on their transition to survivorship. | Qualitative study involving semi-structured interviews with 13 long-term BCSs. | Themes included fear of recurrence, promoting health, seeking a body image, expectations for patient–physician relationships, and positive thinking. | Women transitioning to survivorship face unique psychological and social challenges, emphasizing the need for supportive interventions and resources tailored to their long-term well-being. |

| Coro et al., 2020 [38] | To investigate BCSs’ views on how diet impacts cognitive function and how cancer-related cognitive changes affect their dietary choices. | Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with 15 cancer survivors (13 breast cancer, 2 colorectal cancer) analyzed through thematic analysis. | Identified themes include diet’s impact on cognition and cognition’s impact on diet. | Cancer survivors recognize a reciprocal relationship between diet and cognitive function, emphasizing the importance of personalized nutritional guidance and sustained support for long-term dietary adjustments. |

| Beckenstein et al., 2021 [39] | To explore the acceptability of a 22-week structured diet and exercise weight loss intervention among BCSs with overweight or obesity. | Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with 17 BCS participants who completed the intervention; thematic analysis was conducted. | Four main themes emerged: “1. facilitators of intervention adherence, 2. barriers of intervention adherence, 3. continuation of healthy habits post intervention, and 4. recommendations for intervention improvements”. | Tailored interventions with group exercise, individualized meal provisioning, flexible self-monitoring methods, and tools for transitioning post-intervention are essential for improving adherence and outcomes among BCSs with overweight or obesity |

| Hirschey et al., 2017 [40] | To investigate the shared exercise outcome expectations among BCSs and examine how their cancer diagnosis and treatment shaped these expectations. | Mixed-method descriptive study using semi-structured interviews with 20 BCSs and a modified Outcome Expectations for Exercise (OEE) questionnaire. Data were analyzed using summative content analysis and descriptive statistics. | Three themes emerged: “1. prevalence of common expectations, 2. pervasive impact of fatigue, and 3. a brighter future”. | BCSs often have limited awareness of the benefits of exercise for managing long-term and late treatment effects, underscoring the need for targeted educational interventions to enhance understanding of exercise’s potential impact. |

| Brunet et al., 2013 [41] | To explore the barriers and motivators influencing physical activity participation among women treated for BC. | Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with 9 BCSs (I to III cancer stage); thematic analysis was conducted. | Identified barriers include physical challenges, psychosocial factors, and environmental/organizational obstacles. Motivators included improving health, reducing fatigue, and enhancing quality of life. | Physical activity participation in BCSs is influenced by a complex interplay of barriers and motivators, highlighting the need for tailored strategies to support engagement. |

| S. Kim et al., 2020 [42] | To explore the experience of cancer-related fatigue (CRF), barriers to exercise, and facilitators of exercise adherence among BCSs. | Qualitative study using focus group (FG) interviews with 16 BCSs (6 participants with cancer stage I; 10 with cancer stage II) experiencing moderate-to-severe CRF. Four FG interviews were conducted. Thematic analysis was used to identify key themes. | Identified themes included the insidious nature of CRF, myths about exercise causing recurrence or lymphedema, multiple barriers, and facilitators. | CRF significantly impacts daily life and exercise adherence. Dispelling exercise-related myths and creating tailored, supportive exercise programs for BCSs are essential to promote adherence and manage fatigue effectively. |

| Deery et al., 2023 [43] | To explore BCSs’ attitudes towards health post-treatment, their awareness of co-morbidities, and access to support systems. | Qualitative study utilizing semi-structured interviews with 8 BCSs from Ireland and the UK, analyzed using thematic analysis. | Key themes included health and rehabilitation post-treatment and disparities in access to support services. BCSs highlighted the need for holistic, individualized care addressing diet, exercise, and stress management | Holistic rehabilitation and accessible support services are essential for improving cancer survivorship care. A cancer rehabilitation model, similar to cardiac rehabilitation, could provide comprehensive, lifelong support. |

| Khajoei et al., 2024 [44] | To explore the experiences and multidimensional needs of BCSs during survivorship. | Qualitative content analysis based on semi-structured in-depth interviews with 16 BCSs and four oncologists in Iran from April to July 2023. Data were analyzed inductively to extract central themes. | Identified themes included “1. financial toxicity, 2. family support, 3. informational needs, and 4. psychological and physical issues” | Identifying survivorship needs is critical for developing effective care plans. Financial, emotional, and informational support, along with addressing psychological and physical concerns, enhances BCSs’ quality of life. |

| Chumdaeng et al., 2020 [45] | To explore health behavior changes among Thai BCSs following treatment completion. | Qualitative descriptive study utilizing in-depth interviews with 15 BCSs (staged I to III), analyzed using content analysis. | Health behavior changes were categorized into three key areas: diet modifications to prevent recurrence, regular exercise to mitigate post-treatment complications, and strategies to reduce psychological distress through self-image improvement, relaxation, and spiritual practices | Adherence to health behavior changes is crucial for minimizing post-treatment complications and improving survivors’ quality of life. Tailored interventions by healthcare professionals can enhance these behaviors. |

| Drageset et al., 2016 [46] | To explore individual coping experiences and reflections of women following their first year after primary BC surgery. | Qualitative descriptive study based on individual interviews with 10 Norwegian women (staged I to II) who had undergone primary breast cancer surgery, analyzed using qualitative meaning condensation analysis. | Key themes included existential concerns, diverse emotional responses, active coping strategies, and a desire to return to normalcy. Participants often sought emotional and psychological balance through activities, relationships, and re-prioritizing life values. | Addressing the multidimensional coping strategies and varied needs of BCSs is essential. Tailored support from healthcare professionals can enhance BCSs’ adaptive coping and overall well-being. |

| Şengün et al., 2019 [47] | To explore Turkish BCSs’ experiences related to fear of recurrence (FOR). | Qualitative descriptive study using semi-structured interviews with 12 BCSs (staged I to III), analyzed using inductive content analysis. | Four themes emerged: “1. Quality of fear, 2. Triggers, 3. Effects on life, and 4. Coping strategies.” | Cultural and personal factors, such as fatalistic beliefs and familial roles, strongly influence FOR. Healthcare professionals should incorporate cultural sensitivity and provide supportive environments to address FOR effectively. |

| S. H. Kim et al., 2020 [48] | To explore the self-management needs of BCSs following treatment. | Qualitative FG interviews with 20 BCSs (3 participants with cancer stage I; 6 with cancer stage II; 11 participants with cancer stage III) in South Korea, analyzed thematically to identify key self-management needs. One FG was conducted. | Five themes emerged: “1. Symptom management needs; 2. Emotional management needs; 3. Information acquisition needs; 4. Needs for relationships with healthcare providers; 5. Adaptation needs for adaptation.” | Effective self-management interventions should address knowledge gaps, provide emotional and informational support, and promote tailored adaptations to improve survivorship outcomes. |

| Arem et al., 2024 [49] | To explore young adult cancer survivors’ perspectives on how cancer impacted various domains of their lives post-treatment. | Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with 23 young adult cancer survivors (12 BCSs staged I to IV). Data analyzed using thematic analysis to identify core impacts on life domains. | Key themes included disruptions in relationships, challenges in education and career, financial burdens, and coping mechanisms such as hope, resilience, and redefining life priorities. | Comprehensive survivorship care should address financial, educational, and relational disruptions while promoting coping strategies like resilience and hope to improve quality of life. |

| Mehrabi et al., 2016 [50] | To explore the lived experiences and coping strategies of Iranian women confronting BC diagnosis and its implications. | A qualitative phenomenological study using semi-structured, in-depth interviews with 18 women diagnosed with BC. Data were analyzed thematically. | Two main themes emerged: “emotional turbulence,” including subthemes of uncertainty, fears, and worries, and “threat control,” including coping strategies like seeking support, adopting safe lifestyles, and relying on spirituality. Women experienced significant emotional distress but adopted various coping mechanisms. | Addressing the emotional and practical needs of BCSs is critical. Tailored interventions focusing on emotional support, lifestyle changes, and spiritual resilience can enhance coping and improve quality of life. |

| Country | Study design | Intervention description | Age | Gender | n. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheng et al., 2017 [35] | China | Qualitative approach–Interpretative framework | In-depth interviews | 41–65 | Female | 19 |

| Milosevic et al., 2020 [36] | Canada | Qualitative approach–Interpretative framework | Semi-structured interviews | 18–40 | Female | 12 |

| Fang and Lee, 2016 [37] | Taiwan | Qualitative approach–Interpretative framework | In-depth interviews | 48–72 | Female | 13 |

| Coro et al., 2020 [38] | Australia | Contextualist approach-Interpretative framework | Semi-structured interviews | 27–69 | Female | 13 |

| Beckenstein et al., 2021 [39] | Canada | Qualitative approach–Interpretative framework | Semi-structured interviews | 54–70 | Female | 17 |

| Hirschey et al., 2017 [40] | USA | Qualitative approach–Interpretative framework | Semi-structured interviews | 54–70 | Female | 20 |

| Brunet et al., 2013 [41] | Canada | Qualitative approach–Interpretative framework | Semi-structured, in-depth interviews | / | Female | 9 |

| S. Kim et al., 2020 [42] | Korea | Descriptive approach-Interpretative framework | Focus group | 20–69 | Female | 16 |

| Deery et al., 2023 [43] | UK | Qualitative inductive and reflexive approach | Semi-structured interviews | 45–64 | Female | 8 |

| Khajoei et al., 2024 [44] | Iran | Descriptive approach-Interpretative framework | In-depth interviews | 18–60 | Female | 16 |

| Chumdaeng et al., 2020 [45] | Thailand | Descriptive approach-Interpretative frame-work | In-depth interviews | 33–59 | Female | 15 |

| Drageset et al., 2016 [46] | Norway | Descriptive approach-Interpretative frame-work | Interviews | 48–68 | Female | 10 |

| Şengün et al., 2019 [47] | Turkey | Descriptive approach-Interpretative frame-work | Semi-structured interviews | 33–70 | Female | 12 |

| S. H. Kim et al., 2020 [48] | South Korea | Qualitative approach–Interpretative framework | Focus group | 41–64 | Female | 20 |

| Arem et al., 2024 [49] | USA | Deductive–inductive approach | Semi-structured interviews | 29–38 | Female | 12 |

| Mehrabi et al., 2016 [50] | Iran | Phenomenological design | Semi-structured interviews | 31–65 | Female | 18 |

| Authors | ITEM 1 | ITEM 2 | ITEM 3 | ITEM 4 | ITEM 5 | ITEM 6 | ITEM 7 | ITEM 8 | ITEM 9 | ITEM 10 | Rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheng et al., 2017 [35] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Milosevic et al., 2020 [36] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Fang and Lee, 2016 [37] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Coro et al., 2020 [38] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Beckenstein et al., 2021 [39] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Hirschey et al., 2017 [40] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Brunet et al., 2013 [41] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| S. Kim et al., 2020 [42] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Deery et al., 2023 [43] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Khajoei et al., 2024 [44] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Chumdaeng et al., 2020 [45] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Drageset et al., 2016 [46] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Şengün et al., 2019 [47] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| S. H. Kim et al., 2020 [48] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Arem et al., 2024 [49] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High | |

| Mehrabi et al., 2016 [50] | LG | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| FD | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guardamagna, L.; Diamanti, O.; Artioli, G.; Casole, L.; Bernardi, M.; Bonadies, F.; Zennaro, E.; Modena, G.M.; Nania, T.; Dellafiore, F. Breast Cancer Survivors’ Perception on Health Promotion and Healthy Lifestyle: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071131

Guardamagna L, Diamanti O, Artioli G, Casole L, Bernardi M, Bonadies F, Zennaro E, Modena GM, Nania T, Dellafiore F. Breast Cancer Survivors’ Perception on Health Promotion and Healthy Lifestyle: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071131

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuardamagna, Luca, Orejeta Diamanti, Giovanna Artioli, Lorenzo Casole, Matteo Bernardi, Francesca Bonadies, Enrico Zennaro, Gloria Maria Modena, Tiziana Nania, and Federica Dellafiore. 2025. "Breast Cancer Survivors’ Perception on Health Promotion and Healthy Lifestyle: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071131

APA StyleGuardamagna, L., Diamanti, O., Artioli, G., Casole, L., Bernardi, M., Bonadies, F., Zennaro, E., Modena, G. M., Nania, T., & Dellafiore, F. (2025). Breast Cancer Survivors’ Perception on Health Promotion and Healthy Lifestyle: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071131