Barriers and Promoters of Healthy Eating from the Perspective of Food Environment Perception: From Epidemiology to the Talking Map

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

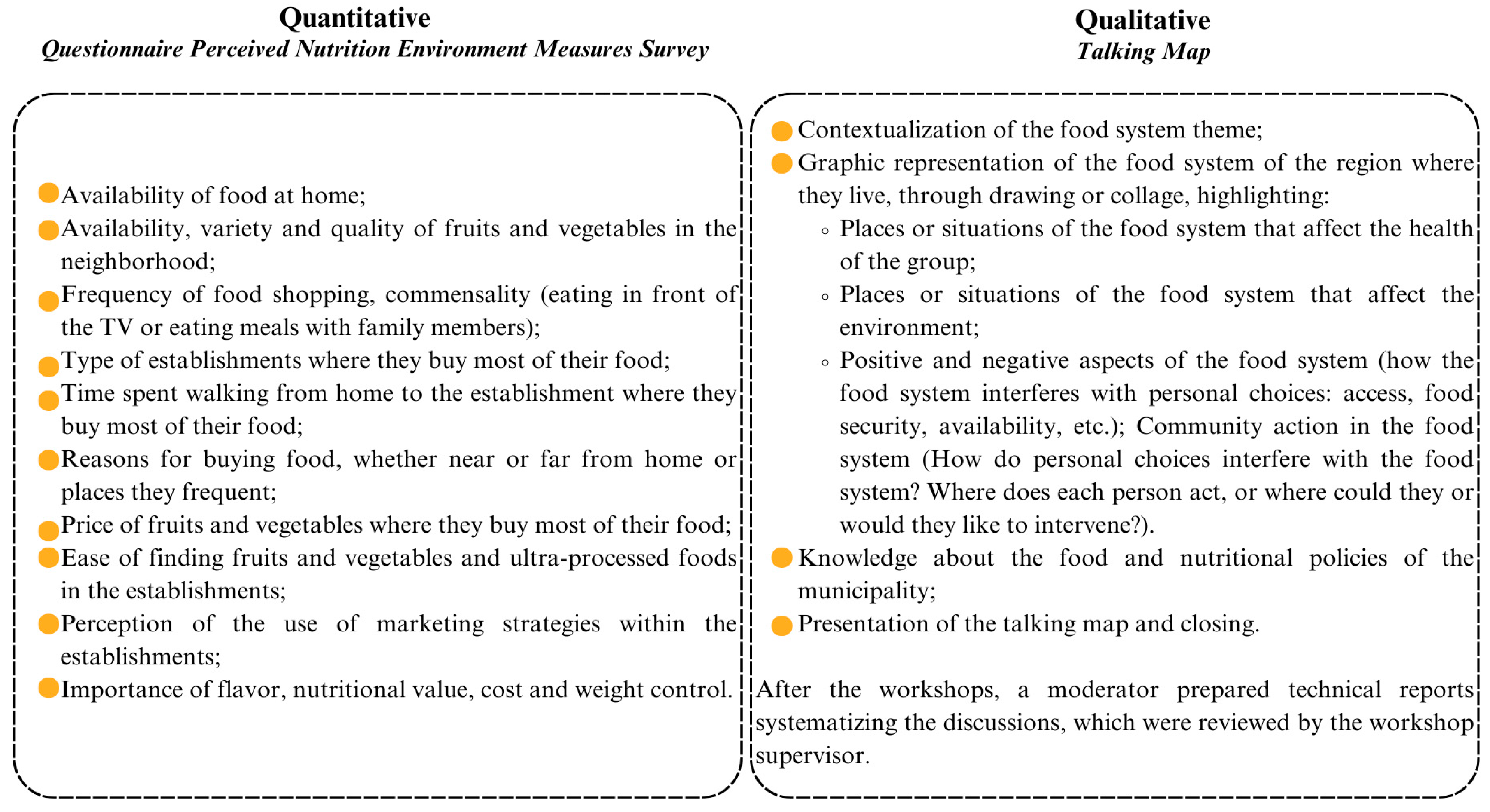

2.2. Assessment of the Perceived Food Environment

2.3. Assessment of the Perceived Food System Based on Talking Map Workshops

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative

3.2. Qualitative

3.2.1. Barriers

Disruption of Commensality

Reduction in Home Gardens

Economic and Logistical Preference for Shopping in Supermarkets and Recognition of the Impacts of UPF Consumption

Lack of Time

Food Transportation and Origin

3.2.2. Promoters

Valuing Street Markets and Local Products

Positive Domestic Practices—Growing Home Gardens

Concerns About Food Systems

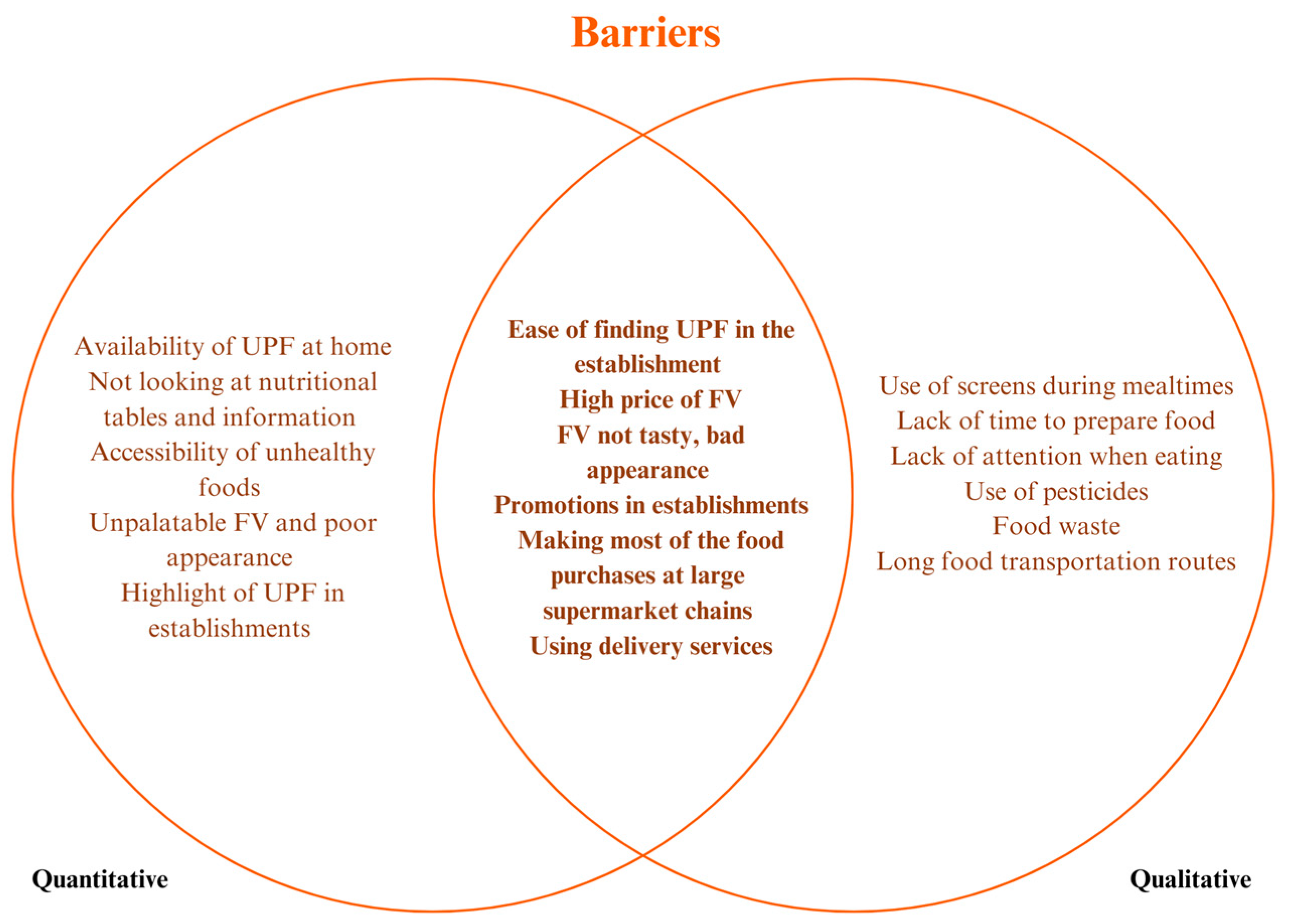

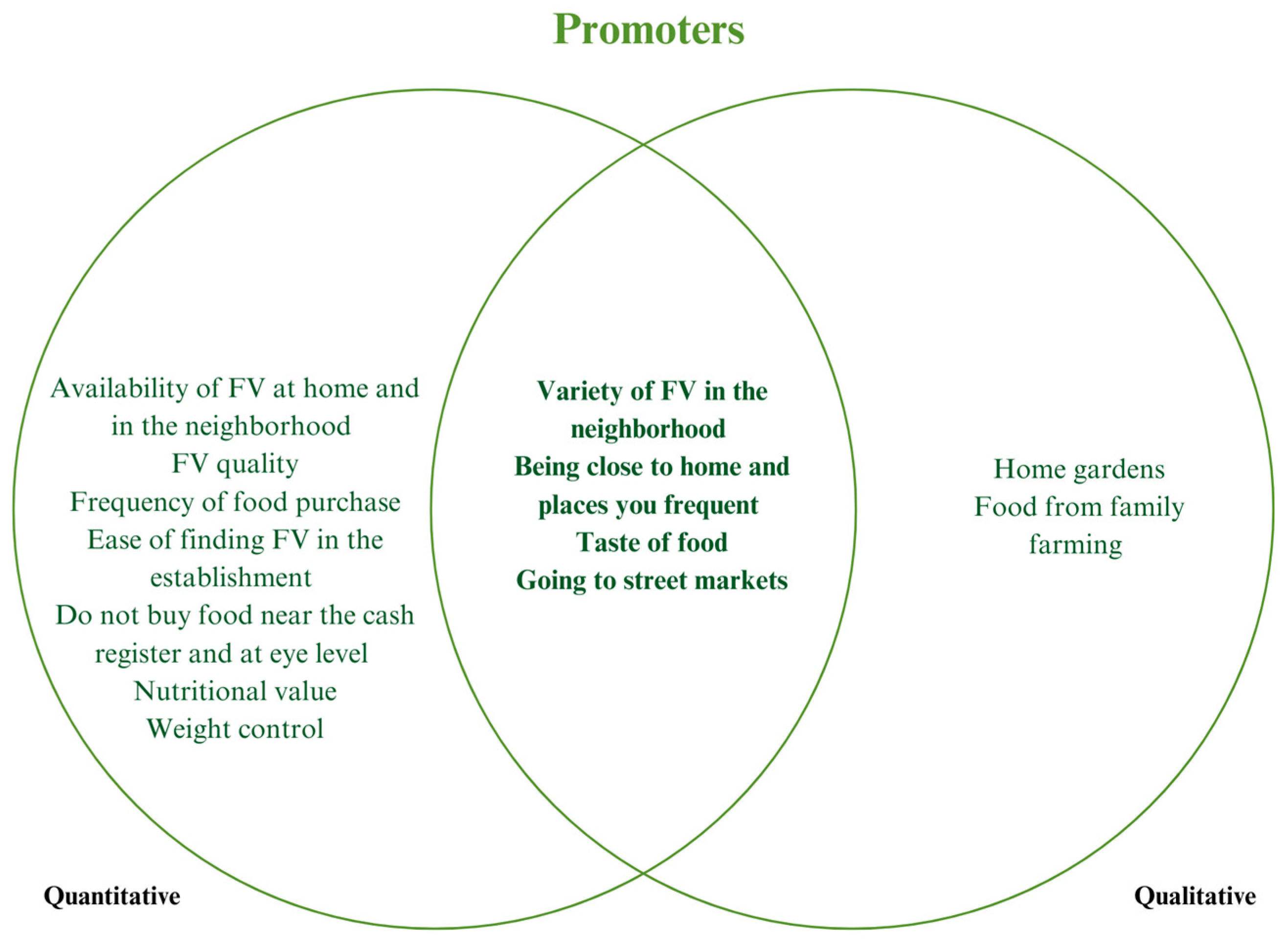

3.3. Intersection of Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches

4. Discussion

4.1. Barriers

4.2. Promoters

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AH | Arterial Hypertension |

| BHU | Basic Health Units |

| FI | Food Insecurity |

| FV | Fruits and Vegetables |

| FHS | Family Health Strategies |

| NCDs | Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases |

| NEMS-P | Perceived Nutrition Environment Measures Survey |

| PHC | Primary Health Care |

| UPF | Ultra-Processed Foods |

References

- Swinburn, B.; Sacks, G.; Vandevijvere, S.; Kumanyika, S.; Lobstein, T.; Neal, B.; Barquera, S.; Friel, S.; Hawkes, C.; Kelly, B.I.; et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non-communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): Overview and key principles. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition, Committee on World Food Security (HLPE). Nutrition and Food Systems. A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security. 2017. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i7846e/i7846e.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Carbonneau, E.; Lamarche, B.; Robitaille, J.; Provencher, V.; Desroches, S.; Vohl, M.-C.; Bégin, C.; Bélanger, M.; Couillard, C.; Pelletier, L.; et al. Social Support, but Not Perceived Food Environment, Is Associated with Diet Quality in French-Speaking Canadians from the PREDISE Study. Nutrients 2019, 11 (Suppl. S12), 3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, C.; Kalamatianou, S.; Drewnowski, A.; Kulkarni, B.; Kinra, S.; Kadiyala, S. Food environment research in low-and ornal-income countries: A systematic scoping review. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Praditsorn, P.; Purnamasari, S.D.; Sranacharoenpong, K.; Arai, Y.; Sundermeir, S.M.; Gittelsohn, J.; Hadi, H.; Nishi, N. Measures of perceived neighborhood food environments and dietary habits: A systematic review of methods and associations. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giskes, K.; Van Lenthe, F.J.; Brug, J.; Mackenbach, J.P.; Turrell, G. Socioeconomic inequalities in food purchasing: The contribution of respondent-perceived and actual (objectively measured) price and availability of foods. Prev. Med. 2007, 45 (Suppl. S1), 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A decade later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11 (Suppl. S1), 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, A.A.; Sharkey, J.; Samuel-Hodge, C.D.; Jones-Smith, J.; Folds, M.C.; Cai, J.; Ammerman, A.S. Perceived and objective measures of the food store environment and the association with weight and diet among low-income women in North Carolina. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14 (Suppl. S6), 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, C.A.; Gabe, K.T.; Canella, D.S.; Jaime, P.C.; Characterization of barriers and facilitators for adequate and healthy eating in the consumer’s food environment. Caracterização das barreiras e facilitadores para alimentação adequada e saudável no ambiente alimentar do consumidor. Cad. Saude Publica 2022, 37 (Suppl 1), e00157020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, L.L.; Friche, A.A.d.L.; Jardim, M.Z.; Junior, P.C.P.d.C.; Oliveira, E.P.; Cardoso, L.d.O.; Mendes, L.L. Percepção dos residentes de favelas brasileiras sobre o ambiente alimentar: Um estudo qualitativo. Cad. Saúde Pública 2024, 40 (Suppl. S3), e00128423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, A.C.; Colley, R.C.; Dasgupta, K.; Minaker, L.M.; Riva, M.; Widener, M.J.; Ross, N.A. Neighborhood Fast-Food Environments and Hypertension in Canadian Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2023, 65 (Suppl. S4), 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ferrer, C.; Auchincloss, A.H.; Barrientos-Gutierrez, T.; Colchero, M.A.; de Oliveira Cardoso, L.; Carvalho de Menezes, M.; Bilal, U. Longitudinal changes in the retail food environment in Mexico and their association with diabetes. Health Place 2020, 66, 102461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armendariz, M.; Pérez-Ferrer, C.; Basto-Abreu, A.; Lovasi, G.S.; Bilal, U.; Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T. Changes in the Retail Food Environment in Mexican Cities and Their Association with Blood Pressure Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19 (Suppl. S3), 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffat, L.F.; Ritchie, L.D.; Gosliner, W.; Plank, K.R.; Au, L.E. Perceived Produce Availability and Child Fruit and Vegetable Intake: The Healthy Communities Study. Nutrients 2021, 13 (Suppl. S11), 3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, J.; Diaz Rios, L.K.; Aldaz, K.J.; De La Cruz, N.; Vu, E.; Asad Asghar, S.; Kuse, Q.; Ortiz, R.M. We Don’t Have a Lot of Healthy Options: Food Environment Perceptions of First-Year, Minority College Students Attending a Food Desert Campus. Nutrients 2019, 11 (Suppl. S4), 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs, S.M.; Ahmed, S.; Fanzo, J.; Herforth, A. Food Environment Typology: Advancing an Expanded Definition, Framework, and Methodological Approach for Improved Characterization of Wild, Cultivated, and Built Food Environments Toward Sustainable Diets. Foods 2020, 9 (Suppl. S4), 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Panorama. Rio Janeiro. 2022. Available online: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/mg/ouro-preto/panorama (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Atlas do Censo Demográfico. Rio Janeiro. 2013. Available online: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/index.php/biblioteca-catalogo?view=detalhes&id=264529 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Avelar, B.A.; Hino, A.A.F.; Santos, A.P.; Mendes, L.L.; Cardoso Carraro, J.C.; Mendonça, R.d.D.; Menezes, M.C.d. Validity and reliability of the Perceived Nutrition Environment Measures Survey (NEMS-P) for use in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 27 (Suppl. S1), e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.H.; Glanz, K. Development of the Perceived Nutrition Environment Measures Survey. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49 (Suppl. S1), 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, L.D.P.; Höfelmann, D.A.; Reis, R.S.; Hino, A.A.F. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Brazilian-Portuguese version of the Perceived Nutrition Environment Measures Survey. Rev. Nutr. 2023, 36, e210254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W.F. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am. J. Health Promot. 1997, 12, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.-C.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuk, T.; Toledo, R.F. O uso de técnicas de pesquisa participativa frente à complexidade do sistema agroalimentar. In Pesquisa Participativa em Saúde: Vertentes e Veredas; Renata Ferraz de, T., Ed.; Instituto de Saúde: São Paulo, Brazil, 2018; 568p. [Google Scholar]

- Freire Paulo. Pedagogia da Autonomia: Saberes Necessários à Prática Educative; Edição, 46; Paz e Terra: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1996; 143p, ISBN 9788577531639. [Google Scholar]

- Landim, F.L.P.; Lourinho, L.A.; Lira, R.C.M.; Santos, Z.M.S.A. Uma reflexão sobre as abordagens em pesquisa com ênfase na integração qualitativo-quantitativa. Rev. Bras. Promoção Saúde 2006, 19, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxy, M.; Malecki, K.C.; Givens, M.L.; Walsh, M.C.; Nieto, F.J. The association between neighborhood economic hardship, the retail food environment, fast food intake, and obesity: Findings from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, M.S.; Lima, S.C.V.C.; de Souza, C.V.S.; Seabra, L.M.J.; de Lyra, C.O. Food environments and association with household food insecurity: A systematic review. Public Health 2024, 224, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, G.C.; Caldeira, T.C.M.; Mais, L.A.; Martins, A.P.B.; Claro, R.M. Food price trends during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2024, 19 (Suppl. S5), e0303777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, E.G.; Passos, C.M.; Levy, R.B.; Martins, A.P.B.; Mais, L.A.; Claro, R.M. What to expect from the price of healthy and unhealthy foods over time? The case from Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23 (Suppl. S4), 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horta, P.M.; Souza, J.P.M.; Freitas, P.P.; Lopes, A.C.S. Food availability and advertising within food outlets around primary healthcare services in Brazil. J. Nutr. Sci. 2020, 9, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrum, C.J.; Waring, M.E.; Cohen, J.F.W.; Stowers, K.C. Within-store fast food marketing: The association between food swamps and unhealthy advertisement. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 35, 102349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.L.; Frank, T.; Ng, S.W.; Swart, E.C. The nutritional composition and in-store marketing of processed and packaged snack foods available at supermarkets in South Africa. Public Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basto-Abreu, A.; Torres-Alvarez, R.; Reyes-Sánchez, F.; González-Morales, R.; Canto-Osorio, F.; Colchero, M.A.; Barquera, S.; Rivera, J.A.; Barrientos-Gutierrez, T. Predicting obesity reduction after implementing warning labels in Mexico: A modeling study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17 (Suppl. S7), e1003221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, N.C.; Andrade, G.M.P.; Ruas, C.M.; Claro, R.M.; Braga, L.V.M.; Nilson, E.A.F.; Anastácio, L.R. Impact of implementation of front-of-package nutrition labeling on sugary beverage consumption and consequently on the prevalence of excess body weight and obesity and related direct costs in Brazil: An estimate through a modeling study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18 (Suppl. S8), e0289340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Fiscal Policies to Promote Healthy Diets: WHO Guideline. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240091016 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Bernardi, E.; Visioli, F. Fostering wellbeing and healthy lifestyles through conviviality and commensality: Underappreciated benefits of the Mediterranean Diet. Nutr. Res. 2024, 126, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, M.L.D.; Pessoa, M.C.; Honório, O.S.; Schubert, M.N.; Schneider, S.; Grisa, C. Dinâmicas de abastecimento nos sistemas alimentares em Belo Horizonte. Confins 2023, 59 (Suppl. S43), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Barniol, M.; Pujol-Busquets, G.; Bach-Faig, A. Screen Time Use and Ultra-Processed Food Consumption in Adolescents: A Focus Group Qualitative Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 124 (Suppl. S10), 1336–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil Ministério da Saúde. Guia Alimentar Para a População Brasileira, 2nd ed.; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, M.S.D.S.; Santos, L.A.D.S. Guias alimentares para a população brasileira: Uma análise a partir das dimensões culturais e sociais da alimentação. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25 (Suppl. S7), 2519–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total (n = 176) | 100% |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 139 | 79.0 |

| Male | 37 | 21.0 |

| Age range | ||

| 20 to 39 years | 74 | 42.0 |

| 40 to 59 years | 102 | 58.0 |

| Skin color | ||

| White | 41 | 23.3 |

| Non-white | 135 | 76.7 |

| Education | ||

| Elementary | 82 | 46.6 |

| Secondary | 65 | 36.9 |

| Salary range | ||

| 1–2 minimum wages | 107 | 60.8 |

| >2 minimum wages | 69 | 39.2 |

| Variables | Answer Options | Total (n = 176) | 100% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Home food environment | |||

| There are FV * in the fridge | Frequently | 144 | 82.8 |

| Rarely | 32 | 18.2 | |

| There are packaged sweets and snacks | Frequently | 27 | 15.3 |

| Rarely | 149 | 84.7 | |

| Community food environment | |||

| It’s easy to buy FV in the neighborhood | I agree | 137 | 77.8 |

| I disagree | 39 | 22.2 | |

| It’s easy to find good quality FV in the neighborhood | I agree | 142 | 80.7 |

| I disagree | 34 | 19.3 | |

| It’s easy to find many options of FV in the neighborhood | I agree | 129 | 73.3 |

| I disagree | 47 | 26.7 | |

| Frequency of food purchases | 1x/week, >1x/week, 1x/2 weeks | 124 | 70.4 |

| Once a month | 42 | 23.9 | |

| Other | 10 | 5.7 | |

| Type of establishment where you buy your food | Supermarket/hypermarket | 150 | 85.2 |

| Grocery store, warehouse or market | 20 | 11.4 | |

| Fair or greengrocer’s market | 6 | 3.4 | |

| Time spent walking to the establishment where you buy most food | 10–20 min | 72 | 41 |

| >21 min | 104 | 59 | |

| Establishment is close to your home | Important | 126 | 71.6 |

| Not important | 50 | 28.4 | |

| It is close to or on the way to other places you frequent | Important | 122 | 69.4 |

| Not important | 52 | 19.5 | |

| Your friends/family shop at this establishment | Important | 81 | 49.5 |

| Not important | 94 | 50.5 | |

| Variety of food options at this establishment | Important | 166 | 94.4 |

| Not important | 10 | 5.6 | |

| Quality of food at this establishment | Important | 173 | 98.3 |

| Not important | 3 | 1.7 | |

| Price of food at this establishment | Important | 164 | 93.2 |

| Not important | 12 | 6.8 | |

| Consumer food environment | |||

| Ease of finding FV at the establishment | Easy | 138 | 78.4 |

| Hard | 38 | 21.6 | |

| Ease of finding packaged sweets and snacks in the store | Easy | 170 | 96.6 |

| Hard | 6 | 3.4 | |

| Ease of finding sugary drinks in the store | Easy | 171 | 97.2 |

| Hard | 5 | 2.8 | |

| Price assessment of FV where most of the food is purchased | Cheap | 63 | 35.8 |

| Expensive | 70 | 39.8 | |

| No fruits and vegetables available | 27 | 15.3 | |

| Fair price for good quality | 8 | 4.5 | |

| Unfair price for poor quality | 8 | 4.5 | |

| I notice signs encouraging me to buy healthy foods | I agree | 51 | 29 |

| I disagree | 125 | 71 | |

| I often buy food near the checkout counter | I agree | 20 | 12.4 |

| I disagree | 154 | 87.6 | |

| Unhealthy foods are usually near the end of the aisles | I agree | 58 | 33.3 |

| I disagree | 116 | 66.7 | |

| I often buy items that are at eye level on the shelves | I agree | 47 | 26.9 |

| I disagree | 128 | 73.1 | |

| There are many signs or displays encouraging me to buy unhealthy foods | I agree | 77 | 44 |

| I disagree | 98 | 56 | |

| I look at the nutritional information tables on most food packages in stores | I agree | 59 | 33.7 |

| I disagree | 116 | 66.3 | |

| I do my shopping through delivery apps and I feel influenced to buy unhealthy foods | I agree | 20 | 11.4 |

| I disagree | 155 | 88.6 | |

| Habits and thoughts about food | |||

| When buying food, taste matters | Important | 173 | 98.3 |

| Not very important | 3 | 1.7 | |

| When buying food, the nutritional value | Important | 153 | 86.9 |

| Not very important | 23 | 13.1 | |

| When buying food, cost matters | Important | 172 | 97.7 |

| Not very important | 4 | 2.3 | |

| When buying food, the ease of finding the food matters | Important | 165 | 94.3 |

| Not very important | 10 | 5.7 | |

| When buying food, the weight control matters | Important | 164 | 93.2 |

| Not very important | 12 | 6.8 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Avelar, B.A.; Santos, A.P.; Vieira, R.A.L.; Mendonça, R.D.D.; Menezes, M.C.d. Barriers and Promoters of Healthy Eating from the Perspective of Food Environment Perception: From Epidemiology to the Talking Map. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071109

Avelar BA, Santos AP, Vieira RAL, Mendonça RDD, Menezes MCd. Barriers and Promoters of Healthy Eating from the Perspective of Food Environment Perception: From Epidemiology to the Talking Map. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071109

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvelar, Bruna Aparecida, Anabele Pires Santos, Renata Adrielle Lima Vieira, Raquel De Deus Mendonça, and Mariana Carvalho de Menezes. 2025. "Barriers and Promoters of Healthy Eating from the Perspective of Food Environment Perception: From Epidemiology to the Talking Map" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071109

APA StyleAvelar, B. A., Santos, A. P., Vieira, R. A. L., Mendonça, R. D. D., & Menezes, M. C. d. (2025). Barriers and Promoters of Healthy Eating from the Perspective of Food Environment Perception: From Epidemiology to the Talking Map. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071109