Children’s Nature Use and Related Constraints: Nationwide Parental Surveys from Norway in 2013 and 2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Which outdoor activities are Norwegian children engaged in, how often, and what are the main changes?

- -

- What are the main constraints on children’s nature engagement, and what are the main changes?

- -

- What kinds of demographic and social variables may explain the observed pattern of constraints?

2. Constraints on Children’s Use of Nearby Nature

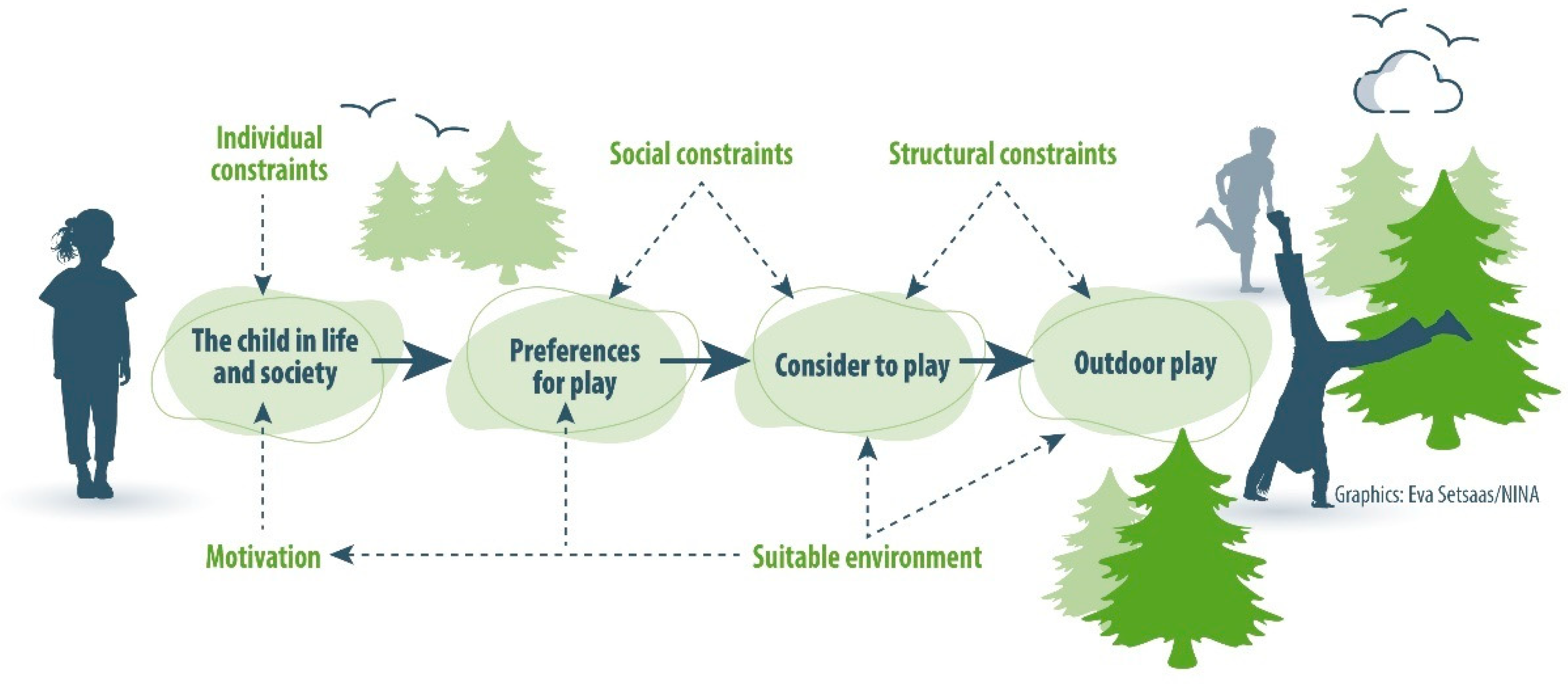

2.1. An Ecological Model for Studying Constraints for Outdoor Play

- Individual, also called ‘intra-personal’ (especially in psychological terms), such as self-image, interests/preferences, age, stage of life, physical health, knowledge, disability, anxiety, fear, attitudes, and personal norms.

- Social, called ‘inter-personal’, such as social circle, lack of play companions, family responsibilities, and a social network for outdoor play.

- Structural, relating to both the private and external environment, such as the socio-cultural factors, economic factors, transportation, time constraints, physical access to play in areas, and the distance to and quality of outdoor spaces. Institutional constraints (e.g., fees, restrictions) are included in this category but are considered less important in Norway due to common rights of access.

2.2. Motivation and Individual/Intra-Personal Constraints

2.3. Social/Inter-Personal Constraints

2.4. Structural Constraints and Environmental Quality

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Target Population, Sampling Technique, and Sample

3.2. Questionnaire and Measurement Methods

3.3. Data Processing and Analyses

3.4. Ethics Approval

4. Results

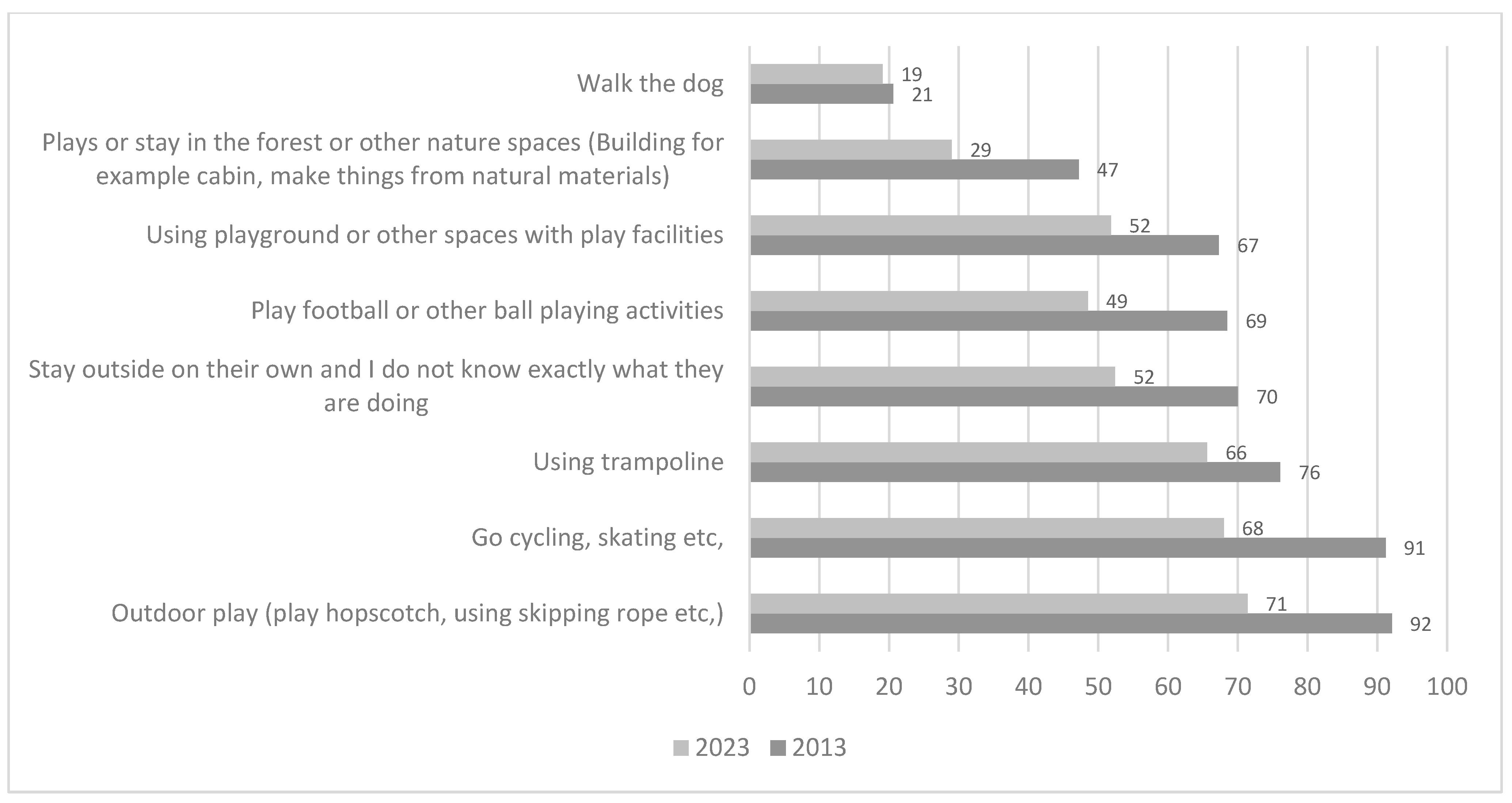

4.1. Changes in Children’s Outdoor Use in Different Neighborhood Settings

4.2. Changes in Parents’ Experiences of Constraints for Children and Youth to Be Outdoors in Natural Settings

4.3. Constraints on Being Outdoors Associated with Demographic, Socio-Economic, and Social Variables

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Comprehensive Decrease in Children’s Greenspace Use

5.2. Significant Increase in Constraints on Children’s Greenspace Use

5.3. Demographic, Socio-Economic, and Social Factors Explaining Children’s Greenspace Use

5.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hofferth, S. Changes in American children’s time, 1997–2003. Electron. Int. J. Time Use Res. 2009, 6, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullan, K. A child’s day: Trends in time use in the UK from 1975 to 2015. Br. J. Sociol. 2018, 70, 997–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, T. The benefits of children’s engagement with nature: A systematic literature review. Child. Youth Environ. 2014, 24, 10–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Benefits of nature contact for children. J. Plan. Lit. 2015, 30, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, S.; Tobin, D.; Avison, W.; Gilliland, J. Mental health benefits of interactions with nature in children and teenagers: A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2018, 72, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantala, O.; Puhakka, R. Engaging with nature: Nature affords well-being for families and young people in Finland. Child. Geogr. 2020, 18, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L.; Keena, K.; Pevec, I.; Stanley, E. Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence. Health Place 2014, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, R. Does access to green space impact the mental well-being of children: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2017, 37, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella-Brodrick, D.A.; Gilowska, K. Effects of nature (greenspace) on cognitive functioning in school children and adolescents: A systematic review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 34, 1217–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, M. De är inte ute så mycket. Den Bostadsnära Naturkontaktens Betydelse och Utrymmet i Storstadsbarns Vardagsliv. Ph.D. Thesis, Institutionen för Kulturgeografi och Ekonomisk Geografi, Handelshögskolan, Göteborg, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fasting, M.L. Vi leker ute!: En Fenomenologisk Hermeneutisk Tilnærming til Barns lek og Lekesteder ute. Ph.D. Thesis, Fakultet for Samfunnsvitenskap og Teknologiledelse, Pedagogisk Institutt, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, H.; Allin, L.; Sandseter, E.B.H.; Ärlemalm-Hagsér, E. Outdoor play and learning in early childhood from different cultural perspectives (Editorial). J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2013, 13, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.; Al-Maiyah, S. Developing an integrated approach to the evaluation of outdoor play settings: Rethinking the position of play value. Child. Geogr. 2022, 20, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. 1989. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Brockman, R.; Jago, R.; Fox, K.R. Children’s active play: Self-reported motivators, constraints and facilitators. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soga, M.; Yamanoi, T.; Tsuchiya, K.; Koyanagi, T.F.; Kanai, T. What are the drivers of and barriers to children’s direct experiences of nature? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 180, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skar, M.; Krogh, E. Changes in children’s nature-based experiences near home: From spontaneous play to adult-controlled, planned and organised activities. Child. Geogr. 2009, 7, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skar, M.; Wold, L.C.; Gundersen, V.; O’Brien, L. Why do children not play in nearby nature? Results from a Norwegian survey. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2016, 16, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Szczytko, R.; Bowers, E.P.; Stephens, L.E.; Stevenson, K.T.; Floy, M.F. Outdoor time, screen time, and connection to nature: Troubling trends among rural youth? Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 966–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; Faulkner, G.; Rhodes, R.E.; Brussoni, M.; Chulak-Bozzer, T.; Ferguson, L.J.; Mitra, R.; O’Reilly, N.; Spence, J.C.; Vanderloo, L.M.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviors of Canadian children and youth: A national survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, A.; George, P.; Ng, M.; Wenden, E.; Bai, P.; Phiri, Z.; Christian, H. Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on Western Australian children’s physical activity and screen time. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, V.; Venter, Z.; Wold, L.C.; Junker-Köhler, B.; Selvaag, S.K. Children’s and Adolescents’ Use of Nature During the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Very Green Country. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.; Figari, H.; Krange, O.; Gundersen, V. Environmental justice in a very green city: Spatial inequality in exposure to urban nature, air pollution and heat in Oslo, Norway. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 858, 160193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, S.; Husain, F.; Scandone, B.; Forsyth, E.; Piggott, H. ‘It’s not for people like (them)’: Structural and cultural constraints to children and young people engaging with nature outdoor schooling. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2023, 23, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, C.; Beckett, A.; Coussens, M.; Desoete, A.; Jones, N.C.; Prellwitz, H.L.; Salkeld, D.F. Constraints to Play and Recreation for Children and Young People with Disabilities: Exploring Environmental Factors; De Gruyter Open Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Loebach, J.; Sanches, M.; Jaffe, J.; Elton-Marshall, T. Paving the way for outdoor play: Examining socio-environmental constraints to community-based outdoor play. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arvidsen, J.; Schmidt, T.; Præstholm, S.; Andkjær, S.; Olafsson, A.S.; Nielsen, J.V.; Schipperijn, J. Demographic, social, and environmental factors predicting Danish children’s greenspace use. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cervero, R.B.; Ascher, W.; Henderson, K.A.; Kraft, M.K.; Kerr, J. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, B.; Bicket, M.; Elliott, B.; Fagan-Watson, B.; Mocca, E.; Hillman, M. Children’s Independent Mobility: An International Comparison and Recommendations for Action; Policy Studies Institute: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Skar, M.; Gundersen, V.; O’Brien, L. How to engage children with nature: Why not just let them play? Child. Geogr. 2016, 14, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, V.; Skår, M.; O’Brien, L.; Wold, L.C.; Follo, G. Children and nearby nature: A nationwide parental survey from Norway. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 17, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Norway. 2023. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/utdanning/barnehager/statistikk/barnehager (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Almeida, A.; Rato, V.; Dabaja, Z.F. Outdoor activities and contact with nature in the Portuguese context: A comparative study between children’s and their parents’ experiences. Child. Geogr. 2023, 21, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, K.A.; Arundell, L.; Cleland, V.; Teychenne, M. Social ecological factors associated with physical activity and screen time amongst mothers from disadvantaged neighborhoods over three years. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.W.; Jackson, E.L.; Godbey, G. A hierarchical model of leisure constraints. Leis. Sci. 1991, 13, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.J.; Virden, R.J. Constraints on Outdoor Recreation. In Constraints to Leisure; Jackson, E.L., Ed.; Venture Publishing: State College, PA, USA, 2005; pp. 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kyttâ, M.; Oliver, M.; Ikeda, E.; Ahmadi, E.; Omiya, I.; Laatikainen, T. Children as urbanites: Mapping the affordances Children’s Geographies and behavior settings of urban environments for Finnish and Japanese children. Child. Geogr. 2018, 16, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, A.M.; Scott, C.; Wishart, L. Infant and toddler responses to a redesign of their childcare outdoor play space. Child. Youth Environ. 2015, 25, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Walker, L.M.; Hardy, S.A.; Christense, K.J. Adolescent hope as a mediator between parent-child connectedness and adolescent outcomes. J. Early Adolesc. 2011, 31, 853–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Olsen, L.L.; Pike, I.; Sleet, D.A. Risky play and children’s safety: Balancing priorities for optimal child development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3134–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, S.; Villanueva, K.; Wood, L.; Christian, H.; Giles-Corti, B. The impact of parents’ fear of strangers and perceptions of informal social control on children’s independent mobility. Health Place 2014, 26, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Restrictive safety or unsafe freedom? Norwegian ECEC practitioners’ perceptions and practices concerning children’s risky play. Childcare Pract. 2012, 18, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjortoft, I. Landscape as playscape: The effects of natural environments on children’s play and motor development. Child. Youth Environ. 2004, 14, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Kennair, L.E.O. Children’s risky play from an evolutionary perspective: The anti-phobic effects of thrilling experiences. Evol. Psychol. 2011, 9, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordbakke, S. Children’s out-of-home leisure activities: Changes during the last decade in Norway. Child. Geogr. 2019, 17, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, L.C.; Broch, T.B.; Vistad, O.I.; Selvaag, S.K.; Gundersen, V.; Øian, H. Barn og unges Organiserte Friluftsliv. Hva Fremmer Gode Opplevelser og Varig Deltagelse? NINA Rapport 2084; Norsk Institutt for Naturforskning: Trondheim, Norway, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Borge, A.I.H.; Nordhagen, R.; Lie, K.K. Children in the environment: Forest day-care centers. Hist. Fam. 2003, 8, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, A.H.; Hägerhäll, C.M. Impact of space requirements on outdoor play areas in public kindergartens. Nord. J. Archit. Res. 2012, 24, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Karsten, L. It all used to be better? Different generations on continuity and change in urban children’s daily use of space. Child. Geogr. 2005, 3, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, N.J. Outdoor risky play and healthy child development in the shadow of the “risk society”: A forest and nature school perspective. Child Youth Serv. 2017, 38, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Sando, O.J. “We don’t allow children to climb trees”: How a focus on safety affects Norwegian children’s play in early-childhood education and care settings. Am. J. Play 2016, 8, 178–200. [Google Scholar]

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Risky play among four-and five-year-old children in preschool. In Proceedings of the Conference Vision into Practice: Making Quality a Reality in the Lives of Young Children, Dublin, Ireland, 8–10 February 2007; pp. 248–256. [Google Scholar]

- Lund Fasting, M.; Høyem, J. Freedom, joy and wonder as existential categories of childhood–reflections on experiences and memories of outdoor play. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2024, 24, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Yan, Z. Factors affecting response rates of the web survey: A systematic review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammut, R.; Griscti, O.; Norman, I.J. Strategies to improve response rates to web surveys: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 123, 104058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, S.L.; Pimlott-Wilson, H. Enriching children, institutionalizing childhood? Geographies of play, extracurricular activities, and parenting in England. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2014, 104, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Insight, creativity and thoughts on the environment: Integrating children and youth into human settlement development. Environ. Urban. 2002, 14, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Childhood experiences associated with care for the natural world: A theoretical framework for empirical results. Child. Youth Environ. 2007, 17, 144–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, L.R.; Whiting, J.W.; Green, G.T. Exploring the influence of outdoor recreation participation on pro-environmental behavior in a demographically diverse population. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, L.C.; Skar, M.; Øian, H. Barn og unges Friluftsliv; NINA Rapport 1801; Norsk Institutt for Naturforskning: Trondheim, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Van Heel, B.F.; van den Born, R.J.G.; Aarts, M.N.C. Everyday childhood nature experiences in an era of urbanisation: An analysis of Dutch children’s drawings of their favourite place to play outdoors. Child. Geogr. 2023, 21, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survey Details | Response Options |

|---|---|

| A. Questions about children’s outdoor use in different neighborhood settings | |

| What do your children do outdoors in the nearby environment during leisure time, and how often? | [dropdown, 5 categories:]

|

| B. Demographic characteristics | |

| Parent: Age and gender, Income, Education, Single parent, Ethnicity, Postal code, Family structure, Number of children, Rural vs. urban living | [dropdown, age—continues] [dropdown, gender] [dropdown, income, 16 categories] [dropdown, education, 6 categories] [dropdown, sole parent, yes/no] [dropdown, ethnicity, 7 categories] [dropdown, family structure, 3 categories] [dropdown, number of children, specify] [dropdown, rural vs. urban living, 4 categories] |

| Child: Age and gender Rural vs. urban living, Postal code | [dropdown, age—continues] [dropdown, gender] [dropdown, urban-rural, 4 categories] [dropdown, postal code, specify] |

| C. Constraints on nature use | |

| To what extent do you agree or disagree that the following statements represent a hindrance for the child to visit nature or green spaces? | [dropdown, Likert scale 1–5, 1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree, 19 statements]

|

| To What Extent Do You Agree or Disagree That the Following Statements Are a Hindrance for the Child to Visit Nature or Green Spaces? | Year | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | Test Statistics Welch’s t-Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The distance to nature and other green areas is too far | 2013 | 3162 | 1.74 | 1.153 | 0.020 | t3325 = −6.903; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 426 | 2.18 | 1.356 | 0.066 | ||

| The child is too busy with leisure time (organized sports and leisure activities) | 2013 | 3163 | 2.56 | 1.212 | 0.022 | t3325 = −8.545; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 426 | 3.04 | 1.236 | 0.060 | ||

| We parents are concerned about traffic | 2013 | 3166 | 2.51 | 1.312 | 0.023 | t3325 = −0.520; p = 0.603; 2023 ≈ 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2.68 | 1.302 | 0.063 | ||

| There is too much bad weather | 2013 | 3155 | 2.03 | 1.123 | 0.020 | t3325 = −5.199; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2.35 | 1.227 | 0.059 | ||

| School homework takes too much time | 2013 | 3166 | 2.53 | 1.135 | 0.020 | t3325 = −0.620; p = 0.535; 2023 ≈ 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2.49 | 1.216 | 0.059 | ||

| The expenses are too high to reach attractive nature and green areas | 2013 | 3159 | 1.34 | 0.743 | 0.013 | t3325 = −7.508; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 1.61 | 0.891 | 0.043 | ||

| There is too high demand for equipment, clothes, shoes, etc. | 2013 | 3172 | 1.51 | 0.860 | 0.015 | t3325 = −7.508; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 1.78 | 0.952 | 0.046 | ||

| The child has poor motor skills | 2013 | 3170 | 1.24 | 0.701 | 0.012 | t3325 = −5.883; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 1.45 | 0.898 | 0.043 | ||

| The child prefers being indoors | 2013 | 3162 | 2.48 | 1.226 | 0.022 | t3325 = −10.554; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 3.07 | 1.279 | 0.062 | ||

| The nature and green areas are poorly facilitated | 2013 | 3139 | 1.58 | 0.920 | 0.016 | t3325 = −4.571; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 1.78 | 1.057 | 0.051 | ||

| The child uses so much time on data and other screens that being outside is downgraded | 2013 | 3166 | 2.34 | 1.221 | 0.022 | t3325 = −9.030; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 426 | 2.80 | 1.339 | 0.065 | ||

| The child does not want to play outdoors in nature | 2013 | 3159 | 2.08 | 1.107 | 0.020 | t3325 = −10.962; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2.61 | 1.192 | 0.058 | ||

| The child lacks friends who want and have time to visit nature and green areas | 2013 | 3141 | 2.21 | 1.166 | 0.021 | t3325 = −10.590; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 426 | 2.77 | 1.259 | 0.061 | ||

| We parents find it unsafe in nature and in green areas | 2013 | 3159 | 1.45 | 0.858 | 0.015 | t3325 = −4.224; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 1.69 | 1.002 | 0.048 | ||

| We parents lack a social network that could increase activity with the child outdoors | 2013 | 3154 | 1.85 | 1.138 | 0.020 | t3325 = −7.602; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2.31 | 1.263 | 0.061 | ||

| We parents prioritize playing and other activities indoors above being outside | 2013 | 3159 | 1.93 | 1.029 | 0.018 | t3325 = −6.619; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2.28 | 1.123 | 0.054 | ||

| We parents have a time schedule filled up with jobs, activities, sports, and other things, and motivating the child to be outside is downgraded | 2013 | 3162 | 2.22 | 1.108 | 0.020 | t3325 = −5.713; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2.54 | 1.174 | 0.057 | ||

| We parents find schoolwork more important than motivating the child to be outside in nature and other green areas | 2013 | 3156 | 2.28 | 1.097 | 0.020 | t3325 = −3.777; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 426 | 2.48 | 1.133 | 0.055 | ||

| We parents find participation in sports and other leisure activities more important than motivating the child to be outside in nature and other green areas | 2013 | 3146 | 2.18 | 1.081 | 0.019 | t3325 = −2.797; p < 0.001; 2023 > 2013 |

| 2023 | 427 | 2.34 | 1.020 | 0.049 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gundersen, V.; Venter, Z.; Vistad, O.I.; Junker-Köhler, B.; Wold, L.C. Children’s Nature Use and Related Constraints: Nationwide Parental Surveys from Norway in 2013 and 2023. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071067

Gundersen V, Venter Z, Vistad OI, Junker-Köhler B, Wold LC. Children’s Nature Use and Related Constraints: Nationwide Parental Surveys from Norway in 2013 and 2023. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071067

Chicago/Turabian StyleGundersen, Vegard, Zander Venter, Odd Inge Vistad, Berit Junker-Köhler, and Line Camilla Wold. 2025. "Children’s Nature Use and Related Constraints: Nationwide Parental Surveys from Norway in 2013 and 2023" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071067

APA StyleGundersen, V., Venter, Z., Vistad, O. I., Junker-Köhler, B., & Wold, L. C. (2025). Children’s Nature Use and Related Constraints: Nationwide Parental Surveys from Norway in 2013 and 2023. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071067