Abstract

Deinstitutionalization is a transition from psychiatric hospitals and other mental health institutions as the primary setting for treatment of individuals with chronic mental health disorders to a range of services, including psychiatric care, that support independent functioning of an individual within the community. The transition has been encouraged by guidelines from the European Expert Group and further specified in the Slovenian Resolution on the National Programme of Mental Health 2018–2028. This integrated systematic and narrative literature review includes 47 international articles from PubMed, along with information on Slovenian mental health legislation and its implementation, to provide insights into deinstitutionalization abroad and its relevance for Slovenia. Although the transition to community-based care is welcomed for promoting independence and respecting individuals’ wants, there are cases where institutional care remains necessary to ensure safety and treatment during the exacerbation of chronic mental health disorders. The quality of care and outcomes generally improve with community-based care. However, the closure of institutions can lead to many unintended consequences, such as the revolving door phenomenon and transinstitutionalization. Both the advantages of community-based care and the important roles of mental health hospitals and other institutions are emphasized.

1. Introduction

Deinstitutionalization or the transition from institutional to community-based care as the primary setting of treatment and care of patients with mental health issues originated from social movements in the beginning of the last century [1]. Institutional care is generally used as a term for psychiatric hospitals and social welfare institutions [2]. Psychiatric hospitals are institutions that provide treatment to patients with acute mental disorders and acute exacerbations of chronic mental illnesses. Most patients need further psychiatric care after completing acute treatment and their discharge from hospitals, which can be done in an outpatient setting. However, some individuals, due to the chronic nature of their illness and resulting functional impairment, need further care and protection, which can be provided through social welfare institutions [3]. This article examines the impact of deinstitutionalization abroad and contextualizes the ongoing transition of mental health care in Slovenia from an integrated biopsychosocial perspective. It welcomes its influence on patients’ well-being and destigmatization, while warning against complete closure of institutional care.

Stigma toward mental health disorders has influenced decision-making regarding the care of psychiatric patients in the past and is still prevalent today. It is associated with both people who suffer from mental health illness and the institutions that treat and care for them. It negatively influences access to care and leads to delay in treatment, increased morbidity, and diminished quality of life of individuals with mental health disorders [4]. The built environment has been known to influence mental health and well-being [5]. Stigma contributed to inadequate financial support and poor facility management of these institutions in the past. Mental health facilities are criticized for poor design, which can worsen patients’ well-being and potentially promote problematic behaviors [6]. Prolonged institutional care can even develop into institutionalism, i.e., a pattern of passive and dependent behavior, which can delay the discharge process or complicate reintegration into the community [7]. Conversely, a well-designed built environment can reduce stress levels, and the intentional architecture and design of mental health institutions can contribute to positive health outcomes [8,9]. In the past, due to stigma, psychiatric hospitals used to be placed in secluded asylums [10]. In Slovenia, these were established in buildings originally designed for other purposes, such as old and run-down castles that are no longer in use [10].

At the beginning of the last century a new social movement, deinstitutionalization, started to spread across Europe, opposing institutional care and criticizing it for isolating residents from their communities, for denying patients control over decisions that affect them, and for institutional requirements taking precedence over individual needs [2]. The initiative promoted not only the closure of institutions but also the development of a range of community-based services. In 1960, this social movement began to influence Slovenia’s approach to mental health services as well. Various civil initiatives advocated both for the reintegration of mental health institution residents to the community and for structural and organizational reforms within the facilities [11,12]. The success of this movement has varied across Europe. A prominent example of the profound shift toward deinstitutionalization occurred in our neighboring country, Italy. Psychiatric institutions were closed, and psychiatric wards were integrated within general hospitals with variable results [10,13]. Slovenia’s psychiatric institutions remained functional, but some were relocated closer to the urban areas, and all were renovated.

Common European Guidelines on the Transition from Institutional to Community-Based Care were published by the European Expert Group on the Transition from Institutional to Community-Based Care in 2012 to ensure deinstitutionalization within the European Union [2]. These guidelines involve measures to prevent the need for institutional care, as well as measures to reintegrate individuals who have already resided in institutional care. They argue that institutions were once seen as the best way of caring for populations with different needs but ultimately attributed to their poorer quality of life and social exclusion. Their work is based on the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which recognizes the right to live independently in the community, and the European Convention on Human Rights, which guarantees the right to private and family life regardless of the nature of the impairment, as well as involvement in all decisions regarding one own’s life. Interference with the latter must be necessary and proportionate. This is further recognized by the World Health Organization, which advocates for a shift to community-based care, arguing that it leads to better outcomes in quality of life, greater cost-efficiency, and stronger respect of human rights. Supporters of deinstitutionalization warn against medicalization and the medical model of disability, which assumes that the disability is caused by a person’s impairment. They argue that the medical model focuses solely on treating individuals’ impairments and promotes segregation. In contrast, they support a social model, which attributes the disability to environmental barriers and focuses on inclusion. The European Expert Group emphasizes that adaptive behavior, such as self-care, communication, academic, social, and community skills, improves, and challenging behavior reduces with the transition to community. Community or independent living should not imply full self-sufficiency but rather the freedom to choose where to live, whom to live with, and how to organize one’s own daily life. The accessibility of the built environment, including transport, technical needs, information, and access to personal assistance and community-based services, plays an important role in this transition [2].

Psychiatric hospitals, as well as social welfare institutions in Slovenia, are still operating but have become closely regulated with legal framework and regulations. An increasing number of studies support the finding that the environment of institutional care influences patients’ recovery [14]. Within the existing structure, changes have been made to improve comfort while ensuring treatment and maintaining security. In Slovenia, facilities and hospital admissions are regulated by the Mental Health Act, which closely monitors the admissions process and special safeguarding measures to ensure respect for personal dignity, human rights, and fundamental freedoms, while also promoting individualized care [3]. Admission to closed wards is usually reserved for acute exacerbations of mental health disorders, with the intention of securing a person’s own safety and the safety of others while initiating treatment. A higher degree of supervision in closed wards is achieved through physically enclosed spaces, an increased number of medical personnel, and special safeguarding measures, while following strict protocols. Closed wards must accommodate no more than two patients per room, provide sufficient space for daily activities, ensure at least two hours of outdoor time per day, and include designated smoking areas. Although patients generally consent to the treatment plan and placement in a closed ward, involuntary hospitalization or placement is possible in an emergency and can be enforced by a court order. Involuntary admission can only be carried out if the less restrictive measures, such as admission to an open ward, outpatient treatment, or supervised treatment, are deemed inappropriate [3].

Social welfare institutions provide continuous special protection and accommodation for individuals that no longer require hospital treatment but still need special care. The law establishes a special form of outpatient treatment called supervised treatment. It is reserved for individuals with severe, chronic mental illness, who have a history of autoaggressive and heteroaggressive behavior, and it is enforced by a court order. This ensures adherence to treatment and helps prevent the recurrence of such behavior, while aiming to avoid institutional placement [3].

The Resolution on the National Programme of Mental Health for the years 2018 to 2028 is the first strategic document on mental health in Slovenia [15]. It assesses the current state of mental well-being in the population and proposes a plan to integrate various community-based actions. It identifies different population groups, each with their specific strategic goals, as well as planned actions to address the major public mental health problems in Slovenia, namely, suicidality and alcoholism. The assessment of institutional mental health care is based on the number of hospitalizations in psychiatric hospitals, which, at the time of the publication, were reportedly below average, while their duration was said to be slightly above the European Union average [16]. Outpatient treatment was relatively sparse, and psychiatric hospitals played a central role in mental health care in Slovenia, a country with approximately two million inhabitants. The resolution substantiates these statements with the following data. In 2016, a total of 4000 residents with chronic mental health disorders and other disabilities under the age of 65 lived in social welfare institutions. Most residents resided in larger departments, while only a few stayed in residential units. The number of institutionalized individuals in 2016 was among the highest in Europe. This emphasis on institutional care is further reflected in data showing that 80% of psychiatrists worked in psychiatric hospitals and other institutional settings [15].

The content of the national resolution is further summarized in the following paragraphs, along with its priorities and a more detailed examination of the action plan. One of the priorities of the national program is the transition to a community-based approach. The document emphasizes individuals’ and relatives’ choice and contributions in planning, implementation, and supervision of different mental health services. The services are designed as a multidisciplinary collaboration, incorporating primary healthcare with health promotion centers, psychiatric hospitals with emergency services, institutional care, mental health centers, community-based treatment coordinators, user-run associations, counseling services, various programs, and social work centers. According to the resolution, 25 new adult mental health centers are to be established, strategically distributed across all regions of Slovenia. These centers should provide triage, crisis intervention, early diagnostics, and treatment of mental health disorders, as well as psychotherapy for individuals, couples, and families. One of their key envisioned tasks is providing acute psychiatric treatment in a home environment, along with intensive monitoring and management of unstable mental health conditions. As such, these centers play a role in preventing the need for hospitalization and institutionalization. When necessary, the resolution predicts their collaboration with other organizations, e.g., referring patients to hospitals and subsequently promoting their return to the community [15].

With the establishment of accessible, comprehensive, and quality community services, the resolution anticipated a 40% reduction in residential capacity in mental health care institutions with planned relocation of their residents to the community. The action plan includes building dedicated residential units. To facilitate the integration of residents who have lived in mental health institutions for years, it provides services and measures to support housing, education, employment, and social activities. Residential groups’ programs offer varying levels of support, allowing individuals to transition between them as their needs change. These programs support individuals starting or returning to school or university and assist with employment. Day care centers offer socialization and activation. Additional services are designed for patients with comorbidity with addiction disorder. For those who need special protection and therefore reside in institutions, the document emphasizes the protection of human rights and dignity within facilities. This is achieved through adequate staffing levels, proper training, and the structural design of the facilities [15].

Researchers and clinicians abroad have expressed their concern in the complete transition to community care. Some countries report a surge of criminality and incarceration of people with severe mental health disorders after the closure of psychiatric hospitals [17,18,19,20,21]. Moreover, the disorders of the imprisoned patients tend to present even more severely than those treated in mental health hospitals [22]. The patients may not be necessarily violent themselves but are more vulnerable to being victims of violent crime in the community [23]. Some studies observe that deinstitutionalization contributes to a worsening of physical health and even to an increased mortality, from both cardiovascular causes and unnatural deaths, including from suicide [20,24].

2. Materials and Methods

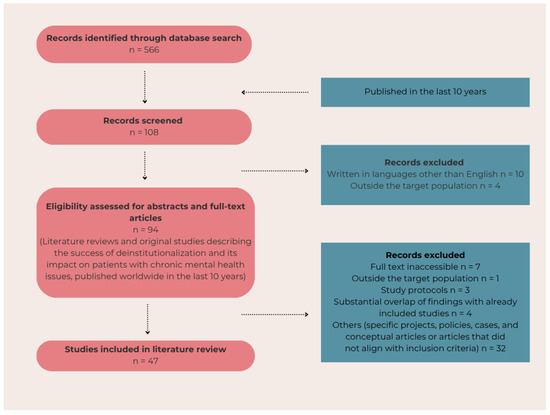

The article integrates a systematic and narrative literature review. The literature review was conducted with the aim of determining whether the ongoing deinstitutionalization process in Slovenia has been studied from a biopsychosocial perspective. The electronic databases PubMed, PubMed Central, and ScienceDirect were used. As only a few Slovenian articles were found on these databases, we broadened our search to worldwide articles on the same topic. Different combinations of keywords were searched, with the most relevant results found on PubMed with the keywords ((deinstitutionalization) OR (deinstitutionalized)) AND ((community care) OR (psychiatric hospital)) AND ((effect) OR (outcome) OR (result)) NOT children NOT elderly, which resulted in 108 articles. The inclusion criteria consisted of literature reviews and original studies describing the success of the transition to community care and its impact on patients with chronic mental health issues, published worldwide in the last 10 years. Exclusion criteria, on the other hand, included inaccessible articles; articles written in languages other than English; study protocols without results; articles with substantial overlap of findings with those already included; studies focusing on the deinstitutionalization of children or older adults; studies addressing outcomes of specific projects, policies, cases, and conceptual paper; and articles that did not align with inclusion criteria. One Slovenian article related to deinstitutionalization was found with this keyword search but was not included, since it focused on older adult and long-term care nursing homes, which exceeds the scope of this review. The articles were screened for their relevance based on abstracts and full-text reviews. The data from the remaining 47 articles were extracted, including their authors and year, title, study design, and key findings. The flow diagram of the literature review and the findings are presented in Figure 1 and Table 1, respectively. These were synthesized and analyzed for methodological approaches, similarities, and differences in perspectives. In addition, a narrative review regarding legislation related to mental health care and transition to community care in Slovenia and European Union was conducted, including the Slovenian Mental Health Act, the Resolution on the National Programme of Mental Health 2018–2028, the Resolution on the National Social Welfare Program for the Period of 2022 to 2030, and the Common European Guidelines on the Transition from Institutional to Community-based Care, as well as the results of the National Mental Health Program, MIRA Program, and Comprehensive Evaluation of the Implementation of the Action Plan 2022–2023.

Figure 1.

The flow diagram of the literature review.

Table 1.

The literature review.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Review

Deinstitutionalization process and community services vary across countries and are therefore challenging for interpretation; moreover, the results are often contradictory. Most countries observe reductions in available beds in psychiatric hospitals and show benefits of community-based care [27,33,37,54,57,66]. On the other hand, while the total number of beds was reduced, there was an increase in the number of psychiatric beds in general hospitals and forensic hospitals and short-stay beds in psychiatric hospitals [19,68]. Evidence that community care improves the quality of care and health outcomes has been shown in fifteen systematic reviews and a retrospective control study [36,41]. A systematic review found that most patients can be successfully discharged from long-stay hospitals to community settings without any clinical deterioration [43]. Transition to community care is beneficial toward patients, regardless of the country’s current level of deinstitutionalization [46].

Some authors describe a link between deinstitutionalization and poorly realized community care that leads to homelessness, crime, and imprisonment, a phenomenon referred to as transinstitutionalization [25,26,27,32]. One review reports an uptick in the suicide rate, while a cohort study indicates that homelessness, imprisonment, and suicide occur only sporadically [26,29,30]. On the other hand, empirical studies have found increased crime rates in Latin America and Korea [40,70]. A comparative cross-sectional control study documented a decline in the suicide rate in Finland [51]. The revolving door effect has been observed, with frequent readmissions to hospitals or patients rotating between shelters, jails, and hospitals [28]. This phenomenon is even more pronounced with rapid discharges and fixed-fee admissions [31,59,62]. A short length of stay below a critical threshold might increase morbidity and mortality [65].

The fewer beds or hospitals that are left are increasingly occupied with patients that are more challenging to treat [33]. Another effect of deinstitutionalization, called boarding, was identified, where patients seek help for mental health issues in insufficiently equipped emergency departments [39]. Deinstitutionalization leads to a change of structure in patients that seek urgent help, with a growing proportion of patients with substance use disorders, personality disorders, trauma-related disorders, and neurodevelopmental disorders that need acute additional protection. A decrease in other diseases, such as depressive disorder, was noted, which seem to be managed well in the community [61]. Furthermore, a notable rise in the use of restraints has been observed, likely due to higher-acuity patients. Great emphasis should be put on the de-escalation and provision of single-occupancy rooms to decrease incidents [61].

A community treatment order is a community-based alternative to forensic psychiatric institutions, which treat patients with mental illness who are involved in legal matters. It helps omit hospitalization, while also enabling rapid admission in cases of mental health deterioration [31,52]. While community care can be a good choice of treatment for many people with severe mental illness, some patients, particularly those with a history of repeated violence, require long-term psychiatric care facilities [28,32].

Deinstitutionalized people often return home, increasing the burden on family members, which has been described by qualitative studies, as well as systematic literature reviews. Family has to cope with the symptoms of the patients, provide care and support, and in cases of exacerbation of health issues may need to decide to involve the police [32,49,65]. Moreover, family members are the most likely targets of violent incidents [45]. The return to the home environment varies, and countries with lower family support tend to observe higher transinstitutionalization [51]. One study reported that due to the distress experienced by family members following discharge without additional support, many expressed a desire for the patient to return to an institution [55].

Countries have reported uneven redistribution of resources and emphasize that the policies should be tailored to the income of the country [29,33,34,58,60,67]. The deinstitutionalization efforts are often influenced by the current broader political situation [42,47,69]. In general, deinstitutionalization in Europe is reasonably successful based on a cross-sectional study and The Quality Indicator for Rehabilitative Care [53]. Most European countries provide both institutional and community-based mental health care, and their transition between the two is not strongly correlated with the number of psychiatric beds per capita [64]. The balanced care model has been proposed to integrate both hospital and community-based services, to provide access for people that need continuity of follow-up and acute treatment during mental health crises [34,44]. More data is needed to determine the minimum number of psychiatric beds per capita required for quality care and patients’ safety [65].

Transition to community care is sometimes unsuccessful, despite multi-professional involvement, and can lead to transinstitutionalization instead of reintegration to the home environment [35]. Community services might be underused, and some deinstitutionalized patients must return to a fully staffed institution. Although deinstitutionalization is associated with higher quality of treatment, a cross-sectional study observed that it was not significantly related to patients’ quality of life or their experiences of care [25]. Instead, the key factors related to the quality of life include symptom severity, low level of social skills, limited self-care, and poor education [63].

Italy, with its Mental Health Reform in 1978 (Law 180), was the first country with a radical transition from psychiatric hospitals to community care. One narrative review showed that neither crime rates nor suicide rates increased. The identified challenges included regional inequality, insufficient human resources, and a lack of scientific research on the process [38]. New legislation addressed the need for forensic psychiatry, introducing community-based structures yielding mixed results [48,50]. The opening of community care centers for forensic patients demonstrated improvement in mental health after the discharge, a reduced need for high-control environments, and a high rate of workplace integration. Reduction in health care costs and positive feedback among mental health workers were reported. However, crucially, the study showed high mortality from the initial discharges (18.2% of the sample of 55 people) and early death (average age of 49 years old) [56].

3.2. Current Mental Health Services in Slovenia

In 2025, there are 19 community-based mental health care centers with interdisciplinary teams, dedicated to the adult population. Additionally, 917 providers are officially registered in healthcare and social services for mental health support, offering free services to users. The information about these institutions is listed on the webpage Mira—National Programme of Mental Health with a search tool that displays programs based on the location or the nature of mental health issues. These providers include psychiatric care, temporary accommodations, consultations, educational programs, youth centers, advocacy, social skills training, humanitarian aid, and various other services [71].

Slovenia has six psychiatric hospitals located across different regions and five social welfare institutions with their smaller, dislocated residential communities. These institutions employ both healthcare workers and other professionals, e.g., social workers. The residents have regular access to family medicine specialists, psychiatrists, and dentists. The number of employees is regulated by law, but they are not necessarily present throughout the entire day. In contrast, community services called residential communities offer a more independent form of housing support. These communities are smaller, accommodate fewer people, and are staffed primarily by non-medical personnel who are generally present only on weekday mornings. The strictness of monitoring medication adherence is usually lower than that of traditional institutions. Their structure is prescribed by The Resolution on the National Social Welfare Program for the Period of 2022 to 2030 and accommodates up to 24 users in each unit [72].

The extent of the effort and appreciation for community-based approach in Slovenia is best described by the following data. The statistics from 2022 show 390 residents of residential groups, 2370 users of day care centers, 1750 users of counseling, 21,587 users of telephone counseling programs, and 617 users of advocacy for mental health. Three different organizations offer helpline counseling service [71]. The Centre for psychological counseling Posvet, located in 18 different cities, conducted 6875 individual counseling sessions and helped 3670 times over the helpline in 2024 [73]. The most prominent examples of deinstitutionalization in Slovenia are the organizations Center for Training, Work and Protection Črna na Koroškem and Dom na Krasu Dutovlje, which are both active in returning residents to the community. The facilities reintegrated 96 and 70 of the former institutional residents [74].

4. Discussion

The process of deinstitutionalization in Slovenia is well documented in the social science literature. These studies emphasize the importance of patient autonomy and trace the historical development of the movement, while also critiquing mental health professionals for their cautious and at times reluctant acceptance of social change [12]. The significance of community-based mental health services in Slovenia has also been highlighted by clinicians [75]. These studies and perspectives are valuable as they initiate necessary dialogue and promote improvements in the quality, safety, and efficacy of treatment. On the other hand, little has been said so far about the risks of this transition and dangers of the complete closure of institutional care in Slovenia. The biopsychosocial perspective is under-represented and under-researched, especially following the adoption of the Resolution on the National Programme of Mental Health, which advocated for a further and accelerated shift toward community care.

Community-based mental health services aim to reduce stigma and improve patient outcomes. These changes promote autonomy and, according to the World Health Organization, enhance the well-being and life satisfaction of people with mental health disorders [76]. As patients’ well-being is inherently connected also to the remission of their illness, Slovenian law recognizes the need to provide prompt and appropriate treatment, even when it may override an individual’s sense of autonomy, in order to ensure their safety and rapid recovery [3,63,77].

Some hospitalizations are due to truly acute conditions, i.e., suicidal ideation during an acute stress reaction, which require immediate treatment and quick resolution. On the other hand, some mental health disorders are chronic, progressive disorders that require continuous treatment. An example of the latter is schizophrenia, one of the fifteen leading causes of disability worldwide [78]. Initially, with proper treatment, hallucination and delusions are only transitory, and the patient may gain insight or come to understand that these experiences are not grounded in reality. As the illness progresses, delusions may become more grandiose and persistent. Perhaps even more damaging to the daily function are other symptoms, such as avolition, social withdrawal, and progressive cognitive impairment. The progression of the disease results in important social and occupational impairment [79].

As clinicians working in psychiatric hospitals, we encounter individuals with various psychiatric disorders who have exhibited violent intentions, toward either themselves or others [80]. In rare cases, this behavior is chronic and unpredictable and can lead to prolonged institutionalization to ensure safety and protection [81,82]. Globally, there is a recognized need for a balanced care model that integrates both community-based and institutional care [34,65].

Global studies highlight potential negative consequences and warn against the complete closure of institutional care. Some studies observe a higher rate of suicide, while others report a surge of criminality and incarceration of people with severe mental health disorders after the closure of psychiatric hospitals [26,40]. This so-called Penrose hypothesis has been observed in Slovenia between 1990 and 2018; however, the effects of even more pronounced transition to community-based care after 2018 have not been studied [83]. Although our systematic literature review challenges these negative claims and includes studies that, in contrast, present evidence of a reduced suicide rate, we urge caution in drawing conclusions as they involve serious consequences. It has been proposed that increases in suicide rates and all-cause mortality may occur if the number of available beds falls below a critical threshold [65]. Further data and studies on the topic are needed.

Surprisingly, the quality of life of the patient might not necessarily increase with deinstitutionalization, whereas family members often experience a heightened burden [84]. Whether the transition resulted in actual inclusion in the broader community is unclear [20,63]. The effects such as transinstitutionalization, boarding, and revolving doors are concerning. Italy reports great success in their deinstitutionalization efforts of forensic patients but simultaneously records high mortality and early death [56].

To our knowledge, this is the first review to integrate Slovenian transition to community care with outcomes of deinstitutionalization abroad, which emphasizes both advantages and risks. Slovenia has made significant and comprehensive steps toward a community-based approach. We believe this to be beneficial for most patients. Despite all the support that community offers, it sometimes still proves to be insufficient. As clinicians working in psychiatric hospitals and mental health institutions, we can attest to several cases where deinstitutionalization has led to unequivocally negative outcomes. This is the case with patients who have severe mental health disorders and require additional protection. Due to reductions and limited availability of institutional capacities, transfer from hospitals to welfare institutions is not possible. These individuals remain hospitalized for months, sometimes even years, in either closed or open wards while waiting for a placement in a social welfare institution. This uncertain situation is unjust for the individual and places additional strain on the overburdened health care system. Although community services are designed to manage acute episodes and prevent admissions and institutional placements, hospitalizations are frequent, and social welfare institutions are in high demand.

Instead of focusing solely on the reduction in institutional capacities, we suggest ongoing, evidence-based efforts toward user-friendly facilities with therapeutic design; strong emphasis on training of mental health professionals; public education to combat stigmatization; and, nonetheless, sufficient funding to make this possible. Further scientific documentation and research are essential to inform future policies and directions.

Limitations

Despite our best efforts, we found very little data on the transition to community care in Slovenia following the implementation of the National Resolution on Mental Health. As such, our conclusions on the current success of deinstitutionalization in our country are limited. Moreover, we describe our clinical experience that resulted from bed reductions in hospitals and social welfare institutions in the discussion but are unable to support it with objective findings. Further empirical studies are necessary to document and evaluate the outcomes of the transition to community care in Slovenia, including its effect on quality of life, disease remission, mortality, caregiver burden, and criminality and its financial implications.

5. Conclusions

Slovenia has taken active steps toward deinstitutionalization and a community-based approach, guided by the Common European Guidelines on the Transition from Institutional to Community-based Care, the Mental Health Act, and the Resolution on the National Programme of Mental Health 2018–2028. These efforts brought positive changes to ensure patients’ well–being and expanded the availability of mental health services to people with mental health issues. However, a complete transition and closure of mental health institutions carries risks. Psychiatric hospitals play a fundamental role in ensuring safety, diagnostics, and treatment during acute phases of psychiatric illness, while social welfare facilities provide support for individuals who require ongoing care due to the chronic nature of their conditions. Instead of moving toward complete closure of mental institutions, we propose continued efforts to ensure the comfort and dignity of patients while providing care and treatment during their most vulnerable moments. The optimal approach to mental health care is the integration of institutional and community-based care. In addition to strengthening versatile community programs, we propose increased funding and support of mental health institutions, along with expanded capacity, to ensure better care of our patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.N.Š. and K.H.G.; methodology, B.N.Š., A.T.S. and K.H.G.; validation, K.H.G.; formal analysis, K.H.G.; resources, K.H.G. and A.T.S.; data curation, K.H.G.; writing—original draft preparation, K.H.G.; writing—review and editing, K.H.G., B.N.Š. and A.T.S.; visualization, K.H.G.; supervision, B.N.Š.; project administration, K.H.G.; funding acquisition, A.T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (Grant Nr. P3-0456).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chow, W.S.; Priebe, S. Understanding Psychiatric Institutionalization: A Conceptual Review. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Expert Group. Common European Guidelines on the Transition from Institutional to Community-Based Care. 2012. Available online: https://deinstitutionalisation.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/guidelines-final-english.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Zakon o Duševnem Zdravju (ZDZdr). 2008. Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=ZAKO2157 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Chukwuma, O.V.; Ezeani, E.I.; Fatoye, E.O.; Benjamin, J.; Okobi, O.E.; Nwume, C.G.; Egberuare, E.N. A Systematic Review of the Effect of Stigmatization on Psychiatric Illness Outcomes. Cureus 2024, 16, e62642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andalib, E.; Diaconu, M.G.; Temeljotov-Salaj, A. Happiness in the Urban Built Environment, People, and Places. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1196, 012090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, N.; Campbell, J.; Priebe, S. How to Design Psychiatric Facilities to Foster Positive Social Interaction—A Systematic Review. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhury, S. Institutionalism in Mental Illnesses: A Case Report. Open Access J. Transl. Med. Res. 2017, 1, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andalib, E.; Temeljotov-Salaj, A.; Steinert, M.; Johansen, A.; Aalto, P.; Lohne, J. The Interplay Between the Built Environment, Health, and Well-Being—A Scoping Review. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connellan, K.; Gaardboe, M.; Riggs, D.; Due, C.; Reinschmidt, A.; Mustillo, L. Stressed Spaces: Mental Health and Architecture. HERD Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2013, 6, 127–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalzadeh, L.; De Filippis, R.; Hayek, S.E.; Mokarar, M.H.; Jatchavala, C.; Koh, E.B.Y.; Larnaout, A.; Noor, I.M.; Ojeahere, M.I.; Orsolini, L.; et al. Impact of Stigma on the Placement of Mental Health Facilities: Insights from Early Career Psychiatrists Worldwide. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1307277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramovš, J. Deinstitucionalizacija Dolgotrajne Oskrbe. Kakov. Starost 2015, 18, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Flaker, V. Kratka Zgodovina Dezinstitucionalizacije v Sloveniji. Časopis Za Krit. Znan. 2012, 40, 13–30, 291, 299. [Google Scholar]

- Morzycka-Markowska, M.; Drozdowicz, E.; Nasierowski, T. Deinstitutionalization in Italian Psychiatry—The Course and consequences Part II. The Consequences of Deinstitutionalization. Psychiatr. Pol. 2015, 49, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molin, J.; Strömbäck, M.; Lundström, M.; Lindgren, B.-M. It’s Not Just in the Walls: Patient and Staff Experiences of a New Spatial Design for Psychiatric Inpatient Care. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 42, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resolucija o Nacionalnem Programu Duševnega Zdravja 2018−2028 (ReNPDZ18–28). Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=RESO120 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Eurostat. Mental Health and Related Issues Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Mental_health_and_related_issues_statistics (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Priebe, S.; Badesconyi, A.; Fioritti, A.; Hansson, L.; Kilian, R.; Torres-Gonzales, F.; Turner, T.; Wiersma, D. Reinstitutionalisation in Mental Health Care: Comparison of Data on Service Provision from Six European Countries. BMJ 2005, 330, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.S.; Priebe, S. How Has the Extent of Institutional Mental Healthcare Changed in Western Europe? Analysis of Data since 1990. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundt, A.P.; Martínez, P.; Jaque, S.; Irarrázaval, M. The Effects of National Mental Health Plans on Mental Health Services Development in Chile: Retrospective Interrupted Time Series Analyses of National Databases between 1990 and 2017. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2022, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredewold, F.; Hermus, M.; Trappenburg, M. ‘Living in the Community’ the Pros and Cons: A Systematic Literature Review of the Impact of Deinstitutionalisation on People with Intellectual and Psychiatric Disabilities. J. Soc. Work 2020, 20, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohanna, D. Deinstitutionalization of People with Mental Illness: Causes and Consequences. AMA J. Ethics 2013, 15, 886–891. [Google Scholar]

- White, P.; Whiteford, H. Prisons: Mental Health Institutions of the 21st Century? Med. J. Aust. 2006, 185, 302–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, T.B.R.; Thomas, S.; Luebbers, S.; Mullen, P.; Ogloff, J.R.P. A Case-Linkage Study of Crime Victimisation in Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders over a Period of Deinstitutionalisation. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, V.; Jacobsen, B.K.; Arnesen, E. Cause-Specific Mortality in Psychiatric Patients after Deinstitutionalisation. Br. J. Psychiatry 2001, 179, 438–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvoskin, J.A.; Knoll, J.L.; Silva, M. A Brief History of the Criminalization of Mental Illness. CNS Spectr. 2020, 25, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybakowski, J. The Fiftieth Anniversary of the Article That Shook up Psychiatry. Psychiatr. Pol. 2023, 57, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkeila, J. Organization of Community Psychiatric Services in Finland. Consort. Psychiatr. 2021, 2, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillman, B.; Smith, E.; Cho, A.; Kennington, C.; Kreis, A. Through the Cracks: The Disposition of Patients With Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders in the Post-Asylum Era. HCA Healthc. J. Med. 2022, 3, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, T.T.; Thornicroft, G. Deinstitutionalisation Does Not Increase Imprisonment or Homelessness. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 412–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, P.; Barrett, B.; McCrone, P.; Csémy, L.; Janousková, M.; Höschl, C. Deinstitutionalised Patients, Homelessness and Imprisonment: Systematic Review. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, S.P. Hospital Utilization Outcomes Following Assignment to Outpatient Commitment. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2021, 48, 942–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, H.R.; Weinberger, L.E. Deinstitutionalization and Other Factors in the Criminalization of Persons with Serious Mental Illness and How It Is Being Addressed. CNS Spectr. 2020, 25, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, H.D.P.; Silva, D.B.D.; Aratani, N.; Arruda, G.O.D.; Lopes, S.G.R.; Palhano, P.S.D.; Saraiva, K.V.D.O.; Brasil, E.G.M. Avanços e Desafios Do Programa de Volta Para Casa Como Estratégia de Desinstitucionalização: Revisão Integrativa. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2022, 27, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornicroft, G.; Deb, T.; Henderson, C. Community Mental Health Care Worldwide: Current Status and Further Developments. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.M.; Souza, Â.C.D.; Silva, A.L.A.D. Deinstitutionalization and Network of Mental Health Services: A New Scene in Health Care. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73 (Suppl. 1), e20180964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulone, I.; Barreto, J.O.M.; Barberato-Filho, S.; Bergamaschi, C.D.C.; Silva, M.T.; Lopes, L.C. Improving Care for Deinstitutionalized People With Mental Disorders: Experiences of the Use of Knowledge Translation Tools. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 575108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, G.A.D.; Cardoso, A.J.C.; Bessoni, E.; Peixoto, A.D.C.; Rudá, C.; Silva, D.V.D.; Branco, S.M.D.J. Modos de Autonomia Em Serviços Residenciais Terapêuticos e Sua Relação Com Estratégias de Desinstitucionalização. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2022, 27, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carta, M.G.; Angermeyer, M.C.; Holzinger, A. Mental Health Care in Italy: Basaglia’s Ashes in the Wind of the Crisis of the Last Decade. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, K.; Berlin, J.; Nash, S.; Shah, S.; Schmelzer, N.; Worley, L. Boarding of Mentally Ill Patients in Emergency Departments: American Psychiatric Association Resource Document. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 20, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebenförcher, M.; Fritz, F.D.; Irarrázaval, M.; Salcedo, A.B.; Dedik, C.; Orellana, A.F.; Ramos, A.H.; Martínez-López, J.N.I.; Molina, C.; Gomez, F.A.R.; et al. Psychiatric Beds and Prison Populations in 17 Latin American Countries between 1991 and 2017: Rates, Trends and an Inverse Relationship between the Two Indicators. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bülow, P.H.; Finkel, D.; Allgurin, M.; Torgé, C.J.; Jegermalm, M.; Ernsth-Bravell, M.; Bülow, P. Aging of Severely Mentally Ill Patients First Admitted before or after the Reorganization of Psychiatric Care in Sweden. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2022, 16, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.D.O.; Lima Júnior, J.M.D.; Portugal, C.M.; Torrenté, M.D. Reforma e Contrarreforma Psiquiátrica: Análise de Uma Crise Sociopolítica e Sanitária a Nível Nacional e Regional. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2019, 24, 4489–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton-Locke, C.; Marston, L.; McPherson, P.; Killaspy, H. The Effectiveness of Mental Health Rehabilitation Services: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 607933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandoni, M.; D’Avanzo, B.; Barbato, A. The Transition towards Community-Based Mental Health Care in the European Union: Current Realities and Prospects. Health Policy 2024, 144, 105081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, P.; Petros, R. Finding Common Ground for Diverging Policies for Persons with Severe Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1193–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salisbury, T.T.; Killaspy, H.; King, M. The Relationship between Deinstitutionalization and Quality of Care in Longer-Term Psychiatric and Social Care Facilities in Europe: A Cross-Sectional Study. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 42, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickling, F.W. Owning Our Madness: Contributions of Jamaican Psychiatry to Decolonizing Global Mental Health. Transcult. Psychiatry 2020, 57, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracuti, S.; Pucci, D.; Trobia, F.; Alessi, M.C.; Rapinesi, C.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Del Casale, A. Evolution of Forensic Psychiatry in Italy over the Past 40 Years (1978–2018). Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2019, 62, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamizi, Z.; Fallahi-Khoshknab, M.; Dalvandi, A.; Mohammadi-Shahboulaghi, F.; Mohammadi, E.; Bakhshi, E. Caregiving Burden in Family Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia: A Qualitative Study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, V.; Veltri, A.; Montanelli, C.; Mundo, F.; Restuccia, G.; Cesari, D.; Maccari, M.; Scarpa, F.; Sbrana, A. Sociodemographic, Clinical and Criminological Characteristics of a Sample of Italian Volterra REMS Patients. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2019, 62, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeniemi, M.; Almeda, N.; Salinas-Pérez, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Colosía, M.R.; García-Alonso, C.; Ala-Nikkola, T.; Joffe, G.; Pirkola, S.; Wahlbeck, K.; Cid, J.; et al. Comparison of Mental Health Care Systems in Northern and Southern Europe: A Service Mapping Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhost, A.; Sirotich, F.; Pridham, K.M.F.; Stergiopoulos, V.; Simpson, A.I.F. Coercion in Outpatients under Community Treatment Orders: A Matched Comparison Study. Can. J. Psychiatry 2018, 63, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killaspy, H.; Cardoso, G.; White, S.; Wright, C.; Caldas De Almeida, J.M.; Turton, P.; Taylor, T.L.; Schützwohl, M.; Schuster, M.; Cervilla, J.A.; et al. Quality of Care and Its Determinants in Longer Term Mental Health Facilities across Europe; a Cross-Sectional Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.; Walcott, G.; Walters, C.; Hickling, F.W. Community Engagement Mental Health Model for Home Treatment of Psychosis in Jamaica. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 522–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokwena, K.E.; Ngoveni, A. Challenges of Providing Home Care for a Family Member with Serious Chronic Mental Illness: A Qualitative Enquiry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, L.; Giunta, G.; Motta, G.; Cavallaro, G.; Martinez, L.; Righetti, A. An Innovative Approach to the Dismantlement of a Forensic Psychiatric Hospital in Italy: A Ten-Year Impact Evaluation. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2023, 19, e174501792212200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chkonia, E.; Geleishvili, G.; Sharashidze, M.; Kuratashvili, M.; Khundadze, M.; Cheishvili, G. The Quality of Care Provided by Outpatient Mental Health Services in Georgia. Consort. Psychiatr. 2021, 2, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes Júnior, H.M.; Desviat, M.; Silva, P.R.F.D. Reforma Psiquiátrica No Rio de Janeiro: Situação Atual e Perspectivas Futuras. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2016, 21, 1449–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Păun, R.-M.; Matei, V.P.; Tudose, C. The Revolving Door Phenomenon in the Romanian Mental Health System. Alpha Psychiatry 2025, 26, 38789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzina, R. Forty Years of the Law 180: The Aspirations of a Great Reform, Its Successes and Continuing Need. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018, 27, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.; Leontieva, L.; Megna, J.L. Shifting Trends in Admission Patterns of an Acute Inpatient Psychiatric Unit in the State of New York. Cureus 2020, 12, e9285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisie, V.; Puiu, M.G.; Manea, M.C.; Moisa, E.; Dumitru, A.M.; Ibadula, L.; Mares, A.M.; Varlam, C.I.; Manea, M. Factors Associated with the Revolving Door Phenomenon in Patients with Schizophrenia: Results from an Acute Psychiatric Hospital in Romania. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 1496750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzouk, D. Accommodation and Health Costs of Deinstitutionalized People with Mental Illness Living in Residential Services in Brazil. Pharmaco. Economics Open 2019, 3, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, T.T.; Killaspy, H.; King, M. An International Comparison of the Deinstitutionalisation of Mental Health Care: Development and Findings of the Mental Health Services Deinstitutionalisation Measure (MENDit). BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, R.; Allison, S.; Bastiampiallai, T. Observed Outcomes: An Approach to Calculate the Optimum Number of Psychiatric Beds. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2019, 46, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myklebust, L.H.; Sørgaard, K.; Wynn, R. How Mental Health Service Systems Are Organized May Affect the Rate of Acute Admissions to Specialized Care: Report from a Natural Experiment Involving 5338 Admissions. SAGE Open Med. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phehlukwayo, S.M.; Tsoka-Gwegweni, J.M. Investigating the Influence of Contextual Factors in the Coordination of Chronic Mental Illness Care in a District Health System. Afr. Health Sci. 2018, 18, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, F.B. From Asylums to Deinstitutionalization and after: An Analytic Review. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2024, 70, 1392–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artvinli, F.; Uslu, M.K.B. On a Long, Narrow Road: The Mental Health Law in Turkey. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2023, 86, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.M.; Sohn, J.H. The Impact of the Mental Health Act Revision for Deinstitutionalization in Korea on the Crime Rate of People with Schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 321, 115089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira Nacionalni Program Duševnega Zdravja. Available online: https://www.zadusevnozdravje.si/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Resolucija o Nacionalnem Programu Socialnega Varstva Za Obdobje 2022–2030 (ReNPSV22–30). Available online: https://pisrs.si/pregledPredpisa?id=RESO137 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Posvet Center Za Psihološko Svetovanje. Poročilo o Delovanju v Letu 2024. Available online: https://posvet.org/2025/01/12/Porocilo-o-Delovanju-v-Letu-2024/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Nacionalni Program za Duševno Zdravje, Program MIRA. Celostna Evalvacija Izvedbe Akcijskega Načrta 2022–2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.zadusevnozdravje.si/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Evalvacija-ukrepov-drugega-AN22-23-F_2024.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Švab, V.; Tomori, M.; Zalar, B.; Ziherl, S.; Dernovšek, M.Z.; Tavčar, R. Community Rehabilitation Service for Patients with Severe Psychotic Disorders: The Slovene Experience. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2002, 48, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Deinstitutionalize Mental Health Care, Strengthen Community-Based Services: WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/Southeastasia/News/Detail/12-03-2024-Deinstitutionalize-Mental-Health-Care--Strengthen-Community-Based-Services--Who (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Yeomans, D.; Taylor, M.; Currie, A.; Whale, R.; Ford, K.; Fear, C.; Hynes, J.; Sullivan, G.; Moore, B.; Burns, T. Resolution and Remission in Schizophrenia: Getting Well and Staying Well. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2010, 16, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/schizophrenia (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Kumari, S.; Dahuja, S.; Singh, U. Association of Clinical Factors with Socio-Occupational Functioning among Individuals with Schizophrenia. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2023, 32, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girasek, H.; Nagy, V.A.; Fekete, S.; Ungvari, G.S.; Gazdag, G. Prevalence and Correlates of Aggressive Behavior in Psychiatric Inpatient Populations. World J. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassnig, M.T.; Nascimento, V.; Deckler, E.; Harvey, P.D. Pharmacological Treatment of Violence in Schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2020, 25, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho De Oliveira, G.; Fraga, M.C.O.; Da Silva, T.P.; Bezerra, H.M.; Martins Valença, A. Factors Associated with Prolonged Institutionalization in Mentally Ill People with and Without a History of Violence and Legal Involvement: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2022, 66, 824–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundt, A.P.; Rozas Serri, E.; Siebenförcher, M.; Alikaj, V.; Ismayilov, F.; Razvodovsky, Y.E.; Hasanovic, M.; Marinov, P.; Frančišković, T.; Cermakova, P.; et al. Changes in National Rates of Psychiatric Beds and Incarceration in Central Eastern Europe and Central Asia from 1990–2019: A Retrospective Database Analysis. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 7, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, M.; Stefanakis, Z.; Panierakis, C.; Michalas, N.; Zografaki, A.; Tsougkou, M.; Vgontzas, A.N. 1183—Deinstitutionalization And Family Burden Following the Psychiatric Reform. Eur. Psychiatry 2013, 28 (Suppl. 1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).