From Hospital to Home: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Optimise Palliative Care Discharge Processes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Procedure and Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Researcher Reflexivity

3. Results

3.1. Sample

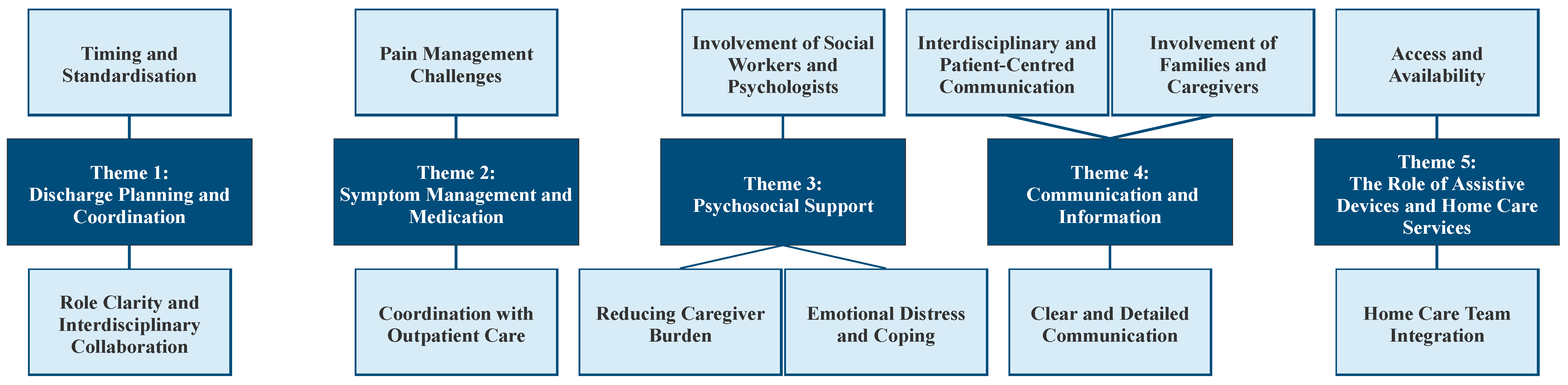

3.2. Results of Qualitative Analysis

3.2.1. Theme 1: Discharge Planning and Coordination

3.2.2. Theme 2: Symptom Management and Medication

3.2.3. Theme 3: Psychosocial Support

3.2.4. Theme 4: Communication and Information

3.2.5. Theme 5: The Role of Assistive Devices and Home Care Services

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization Palliative Care—Key Facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/palliative-care (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- GOEG Österreichischer Strukturplan Gesundheit [Austrian Health Structure Plan]. Available online: https://goeg.at/OESG_2023 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Flierman, I.; Van Seben, R.; Van Rijn, M.; Poels, M.; Buurman, B.M.; Willems, D.L. Health Care Providers’ Views on the Transition Between Hospital and Primary Care in Patients in the Palliative Phase: A Qualitative Description Study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 60, 372–380.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, J.J.; Kamdar, M.M.; Carey, E.C. Top 10 Things Palliative Care Clinicians Wished Everyone Knew About Palliative Care. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2013, 88, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsmüller, S.; Schröer, M. Interprofessionelle Teamarbeit Als Ausgangspunkt Für Palliativmedizin. In Basiswissen Palliativmedizin; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 11–21. ISBN 978-3-662-59285-4. [Google Scholar]

- Muszynski, T.; Dasch, B.; Bernhardt, F.; Lenz, P. Entlassmanagement im Kontext eines Palliativdienstes im Krankenhaus–Entwicklung und Anwendung von Qualitätskriterien. Z. Für Palliativmedizin 2024, 25, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gledhill, K.; Bucknall, T.K.; Lannin, N.A.; Hanna, L. The Role of Collaborative Decision-making in Discharge Planning: Perspectives from Patients, Family Members and Health Professionals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 7519–7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brighton, L.J.; Bristowe, K. Communication in Palliative Care: Talking about the End of Life, before the End of Life. Postgrad. Med. J. 2016, 92, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weetman, K.; Dale, J.; Mitchell, S.J.; Ferguson, C.; Finucane, A.M.; Buckle, P.; Arnold, E.; Clarke, G.; Karakitsiou, D.-E.; McConnell, T.; et al. Communication of Palliative Care Needs in Discharge Letters from Hospice Providers to Primary Care: A Multisite Sequential Explanatory Mixed Methods Study. BMC Palliat. Care 2022, 21, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, M.; Shorting, T.; Mysore, V.K.; Fitzgibbon, E.; Rice, J.; Savigny, M.; Weiss, M.; Vincent, D.; Hagarty, M.; MacLeod, K.K.; et al. Advancing the Care Experience for Patients Receiving Palliative Care as They Transition from Hospital to Home (ACEPATH): Codesigning an Intervention to Improve Patient and Family Caregiver Experiences. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e14002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, S.R.; Killackey, T.; Saunders, S.; Scott, M.; Ernecoff, N.C.; Bush, S.H.; Varenbut, J.; Lovrics, E.; Stern, M.A.; Hsu, A.T.; et al. “Going Home [Is] Just a Feel-Good Idea with No Structure”: A Qualitative Exploration of Patient and Family Caregiver Needs When Transitioning From Hospital to Home in Palliative Care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, e9–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Rojas, M.; García-Vivar, C. The Transition of Palliative Care from the Hospital to the Home: A Narrative Review of Experiences of Patients and Family Caretakers. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2015, 33, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, P.; Trauer, T.; Kelly, B.; O’Connor, M.; Thomas, K.; Zordan, R.; Summers, M. Reducing the Psychological Distress of Family Caregivers of Home Based Palliative Care Patients: Longer Term Effects from a Randomised Controlled Trial. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In Analysing Qualitative Data in Psychology; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2021; pp. 128–147. [Google Scholar]

- Zanetoni, T.C.; Cucolo, D.F.; Perroca, M.G. Interprofessional Actions in Responsible Discharge: Contributions to Transition and Continuity of Care. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2023, 57, e20220452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntz, A.A.; Chen, V.H.; Ambady, L.; Osher, B.; DesRoches, C. Is Routine Discharge Enough? Needs and Perceptions Regarding Discharge and Readmission of Palliative Care Patients and Caregivers. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2025, 10499091241311222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, T.; Scott, M.; Saunders, S.; Varenbut, J.; Howard, M.; Tanuseputro, P.; Webber, C.; Killackey, T.; Wentlandt, K.; Zimmermann, C.; et al. Transitioning From Hospital to Palliative Care at Home: Patient and Caregiver Perceptions of Continuity of Care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSai, C.; Janowiak, K.; Secheli, B.; Phelps, E.; McDonald, S.; Reed, G.; Blomkalns, A. Empowering Patients: Simplifying Discharge Instructions. BMJ Open Qual. 2021, 10, e001419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weetman, K.; MacArtney, J.I.; Grimley, C.; Bailey, C.; Dale, J. Improving Patients’, Carers’ and Primary Care Healthcare Professionals’ Experiences of Discharge Communication from Specialist Palliative Care to Community Settings: A Protocol for a Qualitative Interview Study. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnass, I.; Krutter, S.; Nestler, N. Herausforderungen ambulanter Pflegedienste im Schmerzmanagement von Tumorpatienten: Eine qualitative Untersuchung. Der Schmerz 2018, 32, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzar, E.; Hansen, L.; Kneitel, A.W.; Fromme, E.K. Discharge Planning for Palliative Care Patients: A Qualitative Analysis. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unseld, M.; Meyer, A.L.; Vielgrader, T.-L.; Wagner, T.; König, D.; Popinger, C.; Sturtzel, B.; Kreye, G.; Zeilinger, E.L. Assisted Suicide in Austria: Nurses’ Understanding of Patients’ Requests and the Role of Patient Symptoms. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Paiva, B.S.R.; Paiva, C.E. Personalizing the Setting of Palliative Care Delivery for Patients with Advanced Cancer: “Care Anywhere, Anytime”. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2023, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kötzsch, F.; Stiel, S.; Heckel, M.; Ostgathe, C.; Klein, C. Care Trajectories and Survival after Discharge from Specialized Inpatient Palliative Care—Results from an Observational Follow-up Study. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundereng, E.D.; Dihle, A.; Steindal, S.A. Nurses’ Experiences and Perspectives on Collaborative Discharge Planning When Patients Receiving Palliative Care for Cancer Are Discharged Home from Hospitals. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 3382–3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petchler, C.M.; Singer-Cohen, R.; Fisher, M.C.; DeGroot, L.; Gamper, M.J.; Nelson, K.E.; Peeler, A.; Koirala, B.; Morrison, M.; Abshire Saylor, M.; et al. Palliative Care Research and Clinical Practice Priorities in the United States as Identified by an Interdisciplinary Modified Delphi Approach. J. Palliat. Med. 2024, 27, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, J.M.; Mandrekar, J.N.; Vanderboom, C.E.; Harmsen, W.S.; Kaufman, B.G.; Wild, E.M.; Dose, A.M.; Ingram, C.J.; Taylor, E.E.; Stiles, C.J.; et al. Transitional Palliative Care for Family Caregivers: Outcomes From a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2024, 68, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Number | Age | Role |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 72 | patient |

| P2 | 65 | patient |

| P3 | 60 | patient |

| P4 | 78 | patient |

| P5 | 82 | patient |

| P6 | 58 | relative |

| P7 | 61 | relative |

| P8 | 68 | relative |

| P9 | 74 | relative |

| P10 | 80 | relative |

| P11 | 24 | physician |

| P12 | 28 | nurse |

| P13 | 32 | nurse |

| P14 | 36 | physician |

| P15 | 39 | physician |

| P16 | 41 | nurse |

| P17 | 44 | physician |

| P18 | 48 | physician |

| P19 | 50 | nurse |

| P20 | 53 | physician |

| P21 | 55 | nurse |

| P22 | 56 | physician |

| P23 | 30 | Interdisciplinary professionals |

| P24 | 35 | Interdisciplinary professionals |

| P25 | 40 | Interdisciplinary professionals |

| P26 | 45 | Interdisciplinary professionals |

| P27 | 50 | Interdisciplinary professionals |

| P28 | 55 | Interdisciplinary professionals |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Unseld, M.; Wnendt, T.; Sebesta, C.; van Oers, J.; Parizek, J.; Kum, L.; Masel, E.K.; Mikula, P.; Heppner, H.J.; Zeilinger, E.L. From Hospital to Home: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Optimise Palliative Care Discharge Processes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071023

Unseld M, Wnendt T, Sebesta C, van Oers J, Parizek J, Kum L, Masel EK, Mikula P, Heppner HJ, Zeilinger EL. From Hospital to Home: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Optimise Palliative Care Discharge Processes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(7):1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071023

Chicago/Turabian StyleUnseld, Matthias, Timon Wnendt, Christian Sebesta, Jana van Oers, Jonathan Parizek, Lea Kum, Eva Katharina Masel, Pavol Mikula, Hans Jürgen Heppner, and Elisabeth Lucia Zeilinger. 2025. "From Hospital to Home: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Optimise Palliative Care Discharge Processes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 7: 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071023

APA StyleUnseld, M., Wnendt, T., Sebesta, C., van Oers, J., Parizek, J., Kum, L., Masel, E. K., Mikula, P., Heppner, H. J., & Zeilinger, E. L. (2025). From Hospital to Home: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Optimise Palliative Care Discharge Processes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(7), 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22071023