The Pandemic’s Impact on Mental Well-Being in Sweden: A Longitudinal Study on Life Dissatisfaction, Psychological Distress, and Worries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment of Participants and Data Collection

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Life Dissatisfaction

2.2.2. Psychological Distress

2.2.3. Worries Related to COVID-19

2.2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Sample

3.2. Sex, Age, and Education Differences

3.3. Correlations

3.4. Binary Logistic Regression

4. Discussion

Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Milani, S.A.; Kuo, Y.-F.; Raji, M. COVID-19 and mental health consequences: Moving forward. Lancet Psychiatry 2024, 11, 777–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Physical Activity and COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19/physical-activity-and-covid-19 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Godinić, D.; Obrenovic, B.; Khudaykulov, A. Effects of economic uncertainty on mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic context: Social identity disturbance, job uncertainty and psychological well-being model. Int. J. Innov. Econ. Dev. 2020, 6, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Jiang, D.; Wu, C.; Deng, H.; Su, S.; Buchtel, E.E.; Chen, S.X. Distressed yet bonded: A longitudinal investigation of the COVID-19 pandemic’s silver lining effects on life satisfaction. Am. Psychol. 2024, 79, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramkissoon, H. COVID-19 adaptive interventions: Implications for wellbeing and quality-of-life. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 8109516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Park, C.L.; Calhoun, L.G. (Eds.) The context for posttraumatic growth: Life crises, individual and social resources, and coping. In Posttraumatic Growth; Routledge: London, UK, 1998; pp. 107–132. [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigsson, J.F. How Sweden approached the COVID-19 pandemic: Summary and commentary on the National Commission Inquiry. Acta Paediatr. 2023, 112, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Excess Mortality—Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Excess_mortality_statistics#Recent_data_on_excess_mortality_in_the_EU (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- An, H.Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, C.W.; Yang, H.F.; Huang, W.T.; Fan, S.Y. The relationships between physical activity and life satisfaction and happiness among young, middle-aged, and older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlen, M.; Thorbjørnsen, H.; Sjåstad, H.; von Heideken Wågert, P.; Hellström, C.; Kerstis, B.; Lindberg, D.; Stier, J.; Elvén, M. Changes in physical activity are associated with corresponding changes in psychological well-Being: A pandemic case study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashazadeh Kan, F.; Raoofi, S.; Rafiei, S.; Khani, S.; Hosseinifard, H.; Tajik, F.; Raoofi, N.; Ahmadi, S.; Aghalou, S.; Torabi, F.; et al. A systematic review of the prevalence of anxiety among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 293, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A.; Topino, E. Across the COVID-19 waves; assessing temporal fluctuations in perceived stress, post-traumatic symptoms, worry, anxiety and civic moral disengagement over one year of pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P.; Shevlin, M.; Murphy, J.; McBride, O.; Fox, R.; Bondjers, K.; Karatzias, T.; Bentall, R.P.; Martinez, A.; Vallières, F. A longitudinal assessment of depression and anxiety in the Republic of Ireland before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 300, 113905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhane-Medina, N.Z.; Luque, B.; Tabernero, C.; Castillo-Mayén, R. Factors associated with gender and sex differences in anxiety prevalence and comorbidity: A systematic review. Sci. Prog. 2022, 105, 00368504221135469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viertiö, S.; Kiviruusu, O.; Piirtola, M.; Kaprio, J.; Korhonen, T.; Marttunen, M.; Suvisaari, J. Factors contributing to psychological distress in the working population, with a special reference to gender difference. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, R.; Strough, J.; Bruine de Bruin, W. Age differences in psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: March 2020–June 2021. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1101353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bühler, J.L.; Krauss, S.; Orth, U. Development of relationship satisfaction across the life span: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 147, 1012–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satici, B.; Gocet-Tekin, E.; Deniz, M.E.; Satici, S.A. Adaptation of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Its association with psychological distress and life satisfaction in Turkey. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 19, 1980–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benke, C.; Autenrieth, L.K.; Asselmann, E.; Pané-Farré, C.A. One year after the COVID-19 outbreak in Germany: Long-term changes in depression, anxiety, loneliness, distress and life satisfaction. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 273, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falbová, D.; Kovalčíková, V.; Beňuš, R.; Vorobeľová, L. Long-term consequences of COVID-19 on mental and physical health in young adults. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 32, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TheGlobalEconomy.com. Sweden: Covid Stringency Index. Available online: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Sweden/covid_stringency_index/ (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Haerpfer, C.; Inglehart, R.; Moreno, A.; Welzel, C.; Kizilova, K.; Diez-Medrano, J.; Lagos, M.; Norris, P.; Ponarin, E.; Puranen, B. World Values Survey: Round Seven—Country-Pooled Datafile; JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelzadeh, A.; Sedelius, T. Building Trust in Times of Crisis: A Panel Study of the Influence of Satisfaction With COVID-19 Communication and Management. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2024, 32, e12531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelzadeh, A.; Sedelius, T. Fears, Pandemic, and the Shaping of Social Trust: A Three-Wave Panel Study in Sweden. Scand. Political Stud. 2025, 48, e70007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- The Swedish Government. Law (2003:460) on Ethical Review of Research Involving Humans [Lag (2003:460) om Etikprövning av Forskning Som Avser Människor]; The Swedish Government: Stockholm, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Inglehart, R.; Tay, L. Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 112, 497–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Wahl, I.; Rose, M.; Spitzer, C.; Glaesmer, H.; Wingenfeld, K.; Schneider, A.; Brähler, E. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: Validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 122, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Sweden. Life Expectancy by Region of Birth, Sex and Age. Year 2025–2120. 2025. Available online: https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__BE__BE0401__BE0401A/BefProgLivslangdNb/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Bygren, M.; Gähler, M. Are women discriminated against in countries with extensive family policies? A piece of the “welfare state paradox” puzzle from Sweden. Soc. Polit. Int. Stud. Gend. State Soc. 2021, 28, 921–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliburton, A.E.; Hill, M.B.; Dawson, B.L.; Hightower, J.M.; Rueden, H. Increased stress, declining mental health: Emerging adults’ experiences in college during COVID-19. Emerg. Adulthood 2021, 9, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaninotto, P.; Iob, E.; Di Gessa, G.; Steptoe, A. Recovery of psychological wellbeing following the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal analysis of the English longitudinal study of ageing. Aging Ment. Health 2025, 29, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, E.Ø.; Caspersen, I.H.; Ask, H.; Brandlistuen, R.E.; Trogstad, L.; Magnus, P. Association between work situation and life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: Prospective cohort study in Norway. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e049586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkeli, N.Z. Health, work, and contributing factors on life satisfaction: A study in Norway before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. SSM Popul. Health 2021, 14, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, K. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2020, 16, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settersten, R.A., Jr.; Bernardi, L.; Härkönen, J.; Antonucci, T.C.; Dykstra, P.A.; Heckhausen, J.; Kuh, D.; Mayer, K.U.; Moen, P.; Mortimer, J.T. Understanding the effects of Covid-19 through a life course lens. Adv. Life Course Res. 2020, 45, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.; Shrestha, A.D.; Stojanac, D.; Miller, L.J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women’s mental health. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2020, 23, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, H.; Tanskanen, A.O. “Sandwich generation”: Generational transfers towards adult children and elderly parents. J. Fam. Stud. 2021, 27, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, A.; Peana, M.; Pivina, L.; Srinath, S.; Gasmi Benahmed, A.; Semenova, Y.; Menzel, A.; Dadar, M.; Bjørklund, G. Interrelations between COVID-19 and other disorders. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 224, 108651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starke, K.R.; Reissig, D.; Petereit-Haack, G.; Schmauder, S.; Nienhaus, A.; Seidler, A. The isolated effect of age on the risk of COVID-19 severe outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e006434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Young People’s Concerns During COVID-19: Results from Risks that Matter 2020; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, N.J.; Blazer, D. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Review and commentary of a national academies report. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.E.; Vellas, B. COVID-19 and older adult. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 364–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, P.; Junge, M.; Meaklim, H.; Jackson, M.L. Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: A global cross-sectional survey. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 109, 110236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graupensperger, S.; Cadigan, J.M.; Einberger, C.; Lee, C.M. Multifaceted COVID-19-related stressors and associations with indices of mental health, well-being, and substance use among young adults. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 21, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. *Implementation of the Vaccination Against the Disease COVID-19: An Evaluation* (SOU 2023:73). Swedish Government Official Reports. 2023. Available online: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2023/11/sou-202373/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Kuronen, M.; Virokannas, E.; Salovaara, U. (Eds.) Women, Vulnerabilities and Welfare Service Systems, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

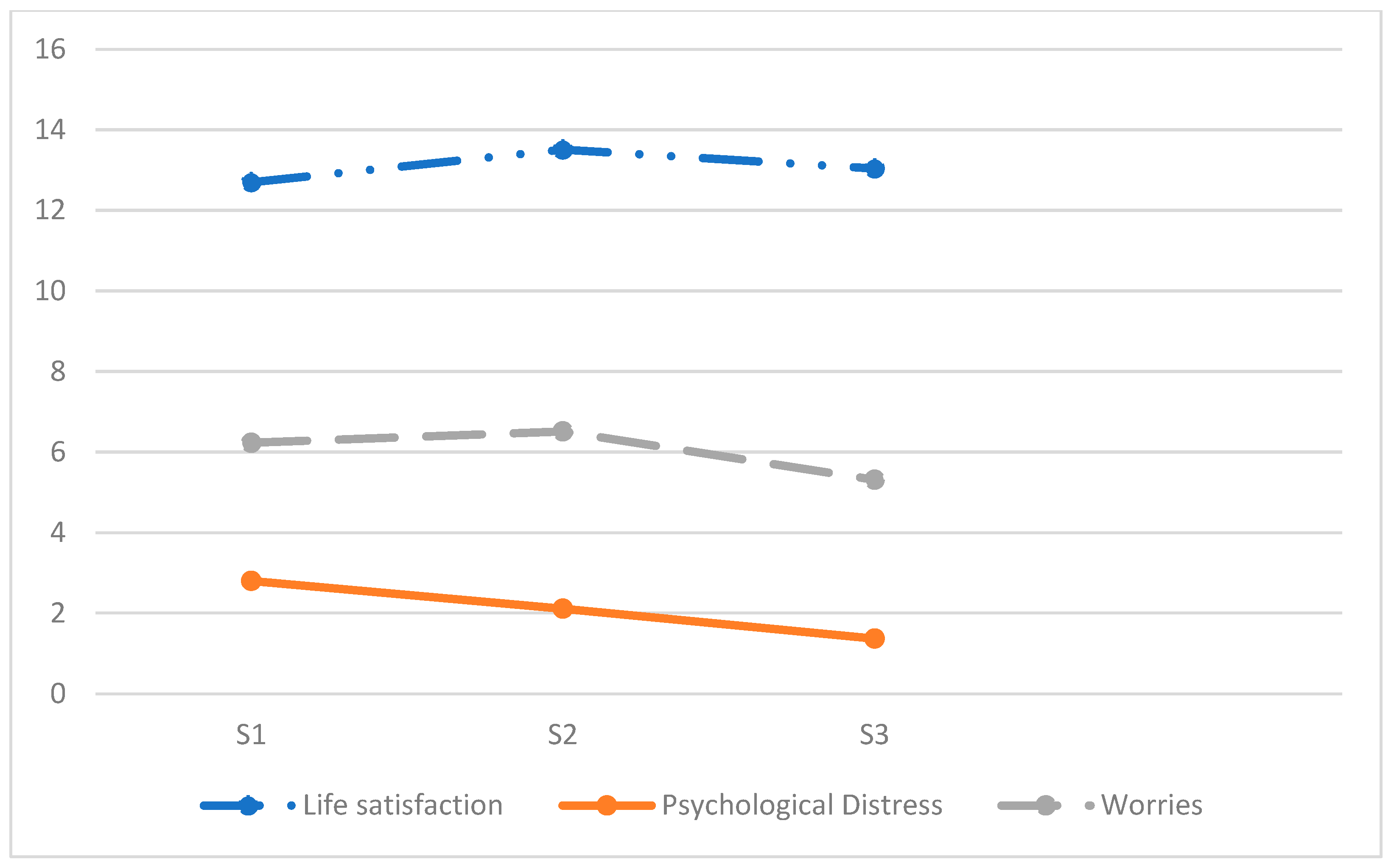

| (a) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | p-Value Between S1 and S2 | p-Value Between S1 and S3 | p-Value Between S2 and S3 | ||

| Life dissatisfaction | |||||||

| Men n = 588 | 12.19 (7.74) | 12.89 (8.12) | 12.67 (7.78) | 0.001 a | 0.019 a | 0.502 a | |

| Women n = 653 | 13.17 (8.52) | 14.07 (8.88) | 13.38 (8.45) | 0.001 a | 0.165 a | 0.009 a | |

| p-value | 0.132 b | 0.064 b | 0.259 b | ||||

| Total N = 1241 | 12.70 (8.17) | 13.51 (8.54) | 13.04 (8.14) | 0.001 a | 0.010 a | 0.015 a | |

| Age groups | |||||||

| 18–29 years n = 121 (9.8%) | 14.32 (8.33) | 15.49 (8.18) | 15.49 (8.38) | 0.057 a | 0.010 a | 0.865 a | |

| 30–49 years n = 360 (29.0%) | 14.17 (8.12) | 14.94 (8.29) | 14.58 (7.93) | 0.028 a | 0.165 a | 0.308 a | |

| 50–64 years n = 358 (28.9%) | 13.46 (8.09) | 14.38 (9.05) | 13.49 (7.98) | 0.001 a | 0.547 a | 0.050 a | |

| 65–79 years n = 402 (32.4%) | 10.23 (7.67) | 10.87 (7.79) | 10.53 (7.80) | 0.008 a | 0.255 a | 0.119 a | |

| p-value total | 0.001 b | 0.001 b | 0.001 b | ||||

| Education | |||||||

| Compulsory/ Senior high school n = 540 (43.6%) | 13.11 (8.14) | 14.04 (8.78) | 13.54 (8.37) | 0.001 a | 0.059 a | 0.019 a | |

| University n = 698 (56.4%) | 12.35 (8.15) | 13.07 (8.30) | 13.62 (7.88) | 0.002 a | 0.085 a | 0.214 a | |

| p-value | 0.064 b | 0.041 b | 0.074 b | ||||

| (b) | |||||||

| Psychological Distress | |||||||

| Men n = 588 | 1.63 (2.60) | 1.66 (2.51) | 1.11 (2.17) | 0.417 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| Women n = 653 | 2.48 (3.18) | 2.52 (3.22) | 1.61 (2.81)) | 0.762 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| p-value | 0.001 b | 0.001 b | 0.003 b | ||||

| Total N = 1241 | 2.08 (2.95) | 2.11 (2.94) | 1.37 (2.54) | 0.461 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| Age groups | |||||||

| 18–29 years n = 121 | 2.88 (3.37) | 3.31 (3.46) | 2.36 (2.48) | 0.098 a | 0.177 a | 0.002 a | |

| 30–49 years n = 360 | 2.08 (2.92) | 2.18 (2.99) | 1.56 (2.77) | 0.461 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| 50–64 years n = 358 | 1.96 (2.72) | 1.96 (2.94) | 1.20 (2.42) | 0.817 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| 65–79 years n = 402 | 1.94 (2.30) | 1.83 (2.64) | 1.07 (2.35) | 0.709 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| p-value | 0.004 c | 0.001 c | 0.001 c | ||||

| Education | |||||||

| Compulsory/Senior high school | 2.13 (3.01) | 2.08 (3.11) | 1.34 (2.49) | 0.597 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| University | 2.04 (2.84) | 2.14 (2.80) | 1.38 (2.54) | 0.140 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| p-value | 0.733 b | 0.105 b | 0.629 b | ||||

| (c) | |||||||

| Worries | |||||||

| Men n = 575 | 5.75 (2.12) | 6.07 (2.31) | 4.89 (2.19) | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| Women n = 653 | 6.67 (2.17) | 6.91 (2.18) | 5.69 (2.27) | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| p-value | 0.001 b | 0.001 b | 0.001 b | ||||

| Total N = 1 241 | 6.23 (2.19) | 6.51 (2.28) | 5.31 (2.27) | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| Age groups | |||||||

| 18–29 years n = 121 | 6.42 (1.96) | 6.66 (2.01) | 5.47 (2.26) | 0.076 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| 30–49 years n = 360 | 6.17 (2.09) | 6.43 (2.06) | 5.36 (2.26) | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| 50–64 years n = 358 | 6.39 (2.21) | 6.63 (2.33) | 5.40 (2.36) | 0.012 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| 65–79 years n = 402 | 6.10 (2.31) | 6.42 (2.45) | 5.11 (2.21) | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| p-value | 0.148 c | 0.475 c | 0.266 c | ||||

| Education | |||||||

| Compulsory/Senior high school n = 540 | 6.30 (2.27) | 6.52 (2.45) | 5.32 (2.22) | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| University n = 698 | 6.19 (2.13) | 6.49 (2.14) | 5.29 (5.31) | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | 0.001 a | |

| p-value | 0.437 b | 0.953 b | 0.734 b | ||||

| Survey 1 Correlation p-Value | Survey 2 Correlation p-Value | Survey 3 Correlation p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life dissatisfaction and Psychological distress | 0.423 ** | 0.481 ** | 0.476 ** |

| Life dissatisfaction and Worries | 0.210 ** | 0.232 ** | 0.252 ** |

| Psychological distress and Worries | 0.486 ** | 0.396 ** | 0.335 ** |

| S1 Correlation p-Value | S2 Correlation p-Value | S3 Correlation p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age × Life dissatisfaction | −0.217 ** | −0.223 ** | −0.244 ** |

| Sex × Life dissatisfaction | NS | NS | NS |

| Education × Life dissatisfaction | NS | −0.058 * | NS |

| Serious illness × Life dissatisfaction | NS | 0.113 ** | 0.108 ** |

| Loss of work × Life dissatisfaction | 0.126 ** | 0.151 ** | NS |

| Age × Psychological distress | −0.083 ** | −0.107 ** | −0.179 ** |

| Sex × Psychological distress | 0.165 ** | 0.158 ** | 0.085 ** |

| Education × Psychological distress | NS | NS | NS |

| Serious illness × Psychological distress | NS | 0.113 ** | 0.108 ** |

| Loss of work × Psychological distress | 0.126 ** | 0.151 ** | NS |

| Age × Worries | NS | NS | NS |

| Sex × Worries | 0.209 ** | 0.182 ** | 0.171 ** |

| Education × Worries | NS | NS | NS |

| Serious illness × Worries | 0.068 * | 0.057 * | NS |

| Loss of work × Worries | 0.060 * | 0.064 * | NS |

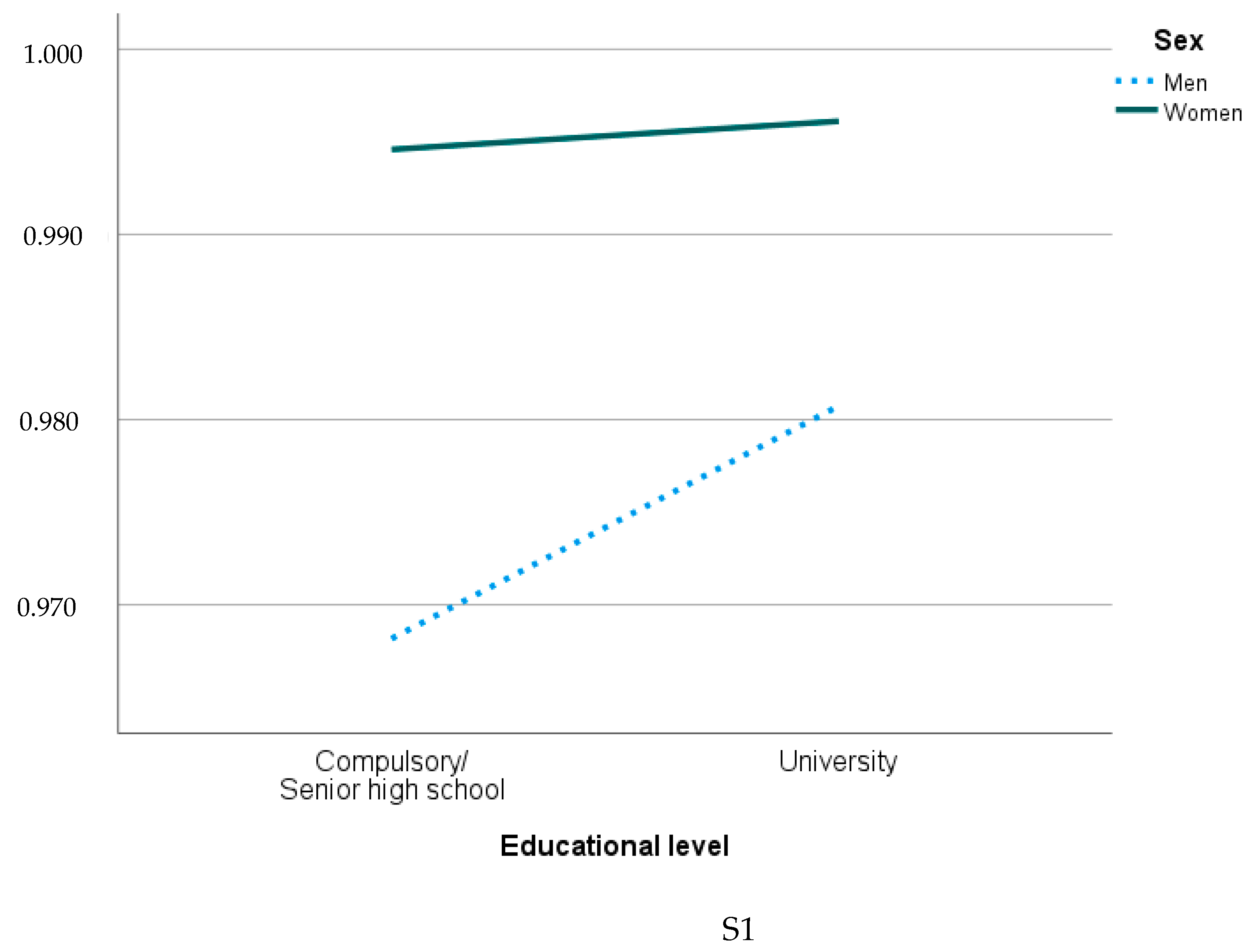

| Life Dissatisfaction S1 | Life Dissatisfaction S2 | Life Dissatisfaction S3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp (B) 95% Cl 1 | Exp (B) 95% Cl 2 | Exp (B) 95% Cl 1 | Exp (B) 95% Cl 2 | Exp (B) 95% Cl 1 | Exp (B) 95% Cl 2 | |

| Age | 0.65 (0.50–0.84) | 2.21 (1.34–3.64) | 0.65 (0.48–0.88) | 0.68 (0.50–0.93) | 0.58 (0.42–0.80) | 0.57 (0.42–0.78) |

| Sex | 2.23 (1.36–3.67) | 0.67 (0.52–0.88) | 1.82 (1.03–3.22) | 1.77 (0.10–3.14) | 1.07 (0.63–1.84) | 1.04 (0.60–1.80) |

| Education | 0.84 (0.52–1.37) | 0.80 (0.49–1.30) | 1.11 (0.64–1.94) | 1.034 (0.59–1.82) | 0.93 (0.54–1.60) | 0.90 (0.52–1.58) |

| Serious illness | 2.69 (0.36–19.79) | 2.52 (0.39–18.81) | - | - | 2.98 (0.72–12.40) | 2.97 (0.70–12.54) |

| Loss of work | - | - | - | - | 0.36 (0.10–1.23) | 0.22 (0.06–0.80) |

| Psychological Distress S1 | Psychological Distress S2 | Psychological Distress S3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp (B) 95% CI 1 | Exp (B) 95% CI 2 | Exp (B) 95% CI 1 | Exp (B) 95% CI 2 | Exp (B) 95% CI 1 | Exp (B) 95% CI 2 | |

| Age | 0.84 (0.75–0.94) | 0.87 (0.78–0.98) | 0.82 (0.73–0.92) | 0.84 (0.74–0.94) | 0.68 (0.60–0.76) | 0.68 (0.60–0.77) |

| Sex | 1.88 (1.50–2.36) | 1.86 (1.48–2.34) | 1.82 (1.45–2.28) | 1.78 (1.41–2.24) | 1.36 (1.08–1.71) | 1.32 (1.04–1.67) |

| Education | 1.13 (0.90–1.42) | 1.092 (0.87–1.38) | 1.18 (0.94–1.48) | 1.13 (0.90–1.43) | 1.07 (0.85–1.35) | 1.05 (0.82–1.33) |

| Serious illness | 2.13 (1.08–4.18) | 2.15 (1.08–4.27) | 1.95 (1.16–3.29) | 1.96 (1.15–3.32) | 1.88 (1.29–2.73) | 1.80 (1.23–2.64) |

| Loss of work | 5.35 (2.07–13.82) | 5.16 (1.98–13.47) | 1.76 (0.91–3.42) | 1.45 (0.74–2.86) | 1.32 (0.62–2.86) | 0.95 (0.43–2.11) |

| Worries S1 | Worries S2 | Worries S3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp (B) 95% CI 1 | Exp (B) 95% CI 2 | Exp (B) 95% CI 1 | Exp (B) 95% CI 2 | Exp (B) 95% CI 1 | Exp (B) 95% CI 2 | |

| Age | 0.60 (0.32–1.10) | 0.60 (0.32–1.12) | 1.27 (0.68–2.36) | 1.36 (0.73–2.52) | 0.94 (0.68–1.32) | 0.97 (0.69–1.36) |

| Sex | 2.81 (0.88–9.00) | 2.63 (0.82–8.46) | 4.49 (0.95–21.23) | 4.40 (0.92–20.93) | 2.37 (1.18–4.77) | 2.26 (1.12–4.55) |

| Education | 1.30 (0.45–3.72) | 1,26 (0.44–3.65) | 3.04 (0.78–11.82) | 2.72 (0.70–10.61) | 1.93 (1.00–3.76) | 1.88 (0.96–3.69) |

| Serious illness | 0.46 (0.06–3.60) | 0.38 (0.05–3.09) | - | - | 0.69 (0.24–1.80) | 0.62 (0.24–1.64) |

| Loss of work | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lindberg, D.; Nilsson, K.W.; Stier, J.; Kerstis, B. The Pandemic’s Impact on Mental Well-Being in Sweden: A Longitudinal Study on Life Dissatisfaction, Psychological Distress, and Worries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 952. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060952

Lindberg D, Nilsson KW, Stier J, Kerstis B. The Pandemic’s Impact on Mental Well-Being in Sweden: A Longitudinal Study on Life Dissatisfaction, Psychological Distress, and Worries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):952. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060952

Chicago/Turabian StyleLindberg, Daniel, Kent W. Nilsson, Jonas Stier, and Birgitta Kerstis. 2025. "The Pandemic’s Impact on Mental Well-Being in Sweden: A Longitudinal Study on Life Dissatisfaction, Psychological Distress, and Worries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 952. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060952

APA StyleLindberg, D., Nilsson, K. W., Stier, J., & Kerstis, B. (2025). The Pandemic’s Impact on Mental Well-Being in Sweden: A Longitudinal Study on Life Dissatisfaction, Psychological Distress, and Worries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 952. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060952