Family Functioning and Pubertal Maturation in Hispanic/Latino Children from the HCHS/SOL Youth

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Family Dysfunction

2.3. Sex

2.4. Pubertal Maturation

2.5. Covariates

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

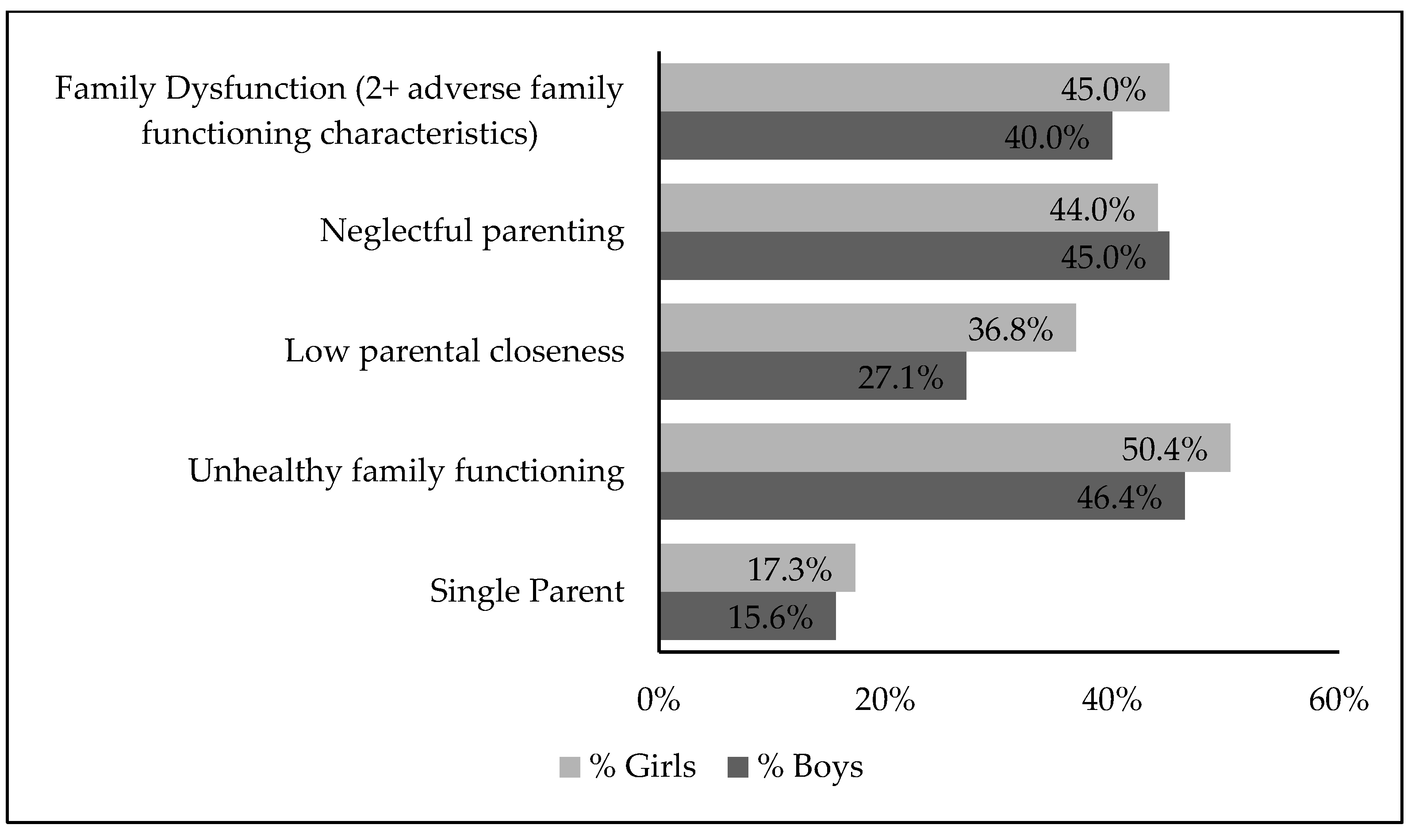

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Family Dysfunction

3.3. Pubertal Development Scale Scores

3.4. Multivariable Regression Models—Family Dysfunction and Pubertal Maturation

3.5. Multivariable Regression Models—Adverse Family Functioning Characteristics (Single Parent, Poor Family Functioning, Low Parental Closeness, Neglectful Parenting) and Pubertal Maturation

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joos, C.M.; Wodzinski, A.M.; Wadsworth, M.E.; Dorn, L.D. Neither antecedent nor consequence: Developmental integration of chronic stress, pubertal timing, and conditionally adapted stress response. Dev. Rev. 2018, 48, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, M.E.; Lewis, S.J.; Bonilla, C.; Smith, G.D.; Joinson, C. Association of timing of menarche with depressive symptoms and depression in adolescence: Mendelian randomisation study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltiala-Heino, R.; Marttunen, M.; Rantanen, P.; Rimpela, M. Early puberty is associated with mental health problems in middle adolescence. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltz, A.M.; Corley, R.P.; Bricker, J.B.; Wadsworth, S.J.; Berenbaum, S.A. Modeling pubertal timing and tempo and examining links to behavior problems. Dev. Psychol. 2014, 50, 2715–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallicchio, L.; Flaws, J.A.; Smith, R.L. Age at menarche, androgen concentrations, and midlife obesity: Findings from the Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause 2016, 23, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, L.; Millwood, I.Y.; Peters, S.A.E.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Bian, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, L.; Feng, S.; et al. Age at menarche and risk of major cardiovascular diseases: Evidence of birth cohort effects from a prospective study of 300,000 Chinese women. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 227, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, K.A.; Gerlovin, H.; Bethea, T.N.; Palmer, J.R. Pubertal growth and adult height in relation to breast cancer risk in African American women. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 141, 2462–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; Ruttle, P.L.; Boyce, W.T.; Armstrong, J.M.; Essex, M.J. Early adversity, elevated stress physiology, accelerated sexual maturation, and poor health in females. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.J.; Del Giudice, M. Developmental Adaptation to Stress: An Evolutionary Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, J.A.; Lewinsohn, P.M.; Seeley, J.R.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Is psychopathology associated with the timing of pubertal development? J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 1768–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; Steinberg, L.; Draper, P. Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: And evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Dev. 1991, 62, 647–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, F.R.; Elks, C.E.; Murray, A.; Ong, K.K.; Perry, J.R. Puberty timing associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and also diverse health outcomes in men and women: The UK Biobank study. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.J. Timing of pubertal maturation in girls: An integrated life history approach. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 920–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E. Individual differences are accentuated during periods of social change: The sample case of girls at puberty. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livson, N.; Peskin, H. Perspectives on adolescence from longitudinal research. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology; Adelson, J., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 47–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.S.; Schubert, C.M. Prolonged juvenile States and delay of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors: The Fels Longitudinal study. J. Pediatr. 2009, 155, S7.e1-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M.; Ellis, B.J.; Shirtcliff, E.A. The Adaptive Calibration Model of stress responsivity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 1562–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, L.D.; Rossignoli, M.T.; Delfino-Pereira, P.; Garcia-Cairasco, N.; de Lima Umeoka, E.H. A Comprehensive Overview on Stress Neurobiology: Basic Concepts and Clinical Implications. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleil, M.E.; Adler, N.E.; Appelhans, B.M.; Gregorich, S.E.; Sternfeld, B.; Cedars, M.I. Childhood adversity and pubertal timing: Understanding the origins of adulthood cardiovascular risk. Biol. Psychol. 2013, 93, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semiz, S.; Kurt, F.; Kurt, D.T.; Zencir, M.; Sevinc, O. Factors affecting onset of puberty in Denizli province in Turkey. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2009, 51, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, L.; Frigon, J.Y. Precocious puberty in adolescent girls: A biomarker of later psychosocial adjustment problems. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2005, 36, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arim, R.G.; Tramonte, L.; Shapka, J.D.; Dahinten, V.S.; Willms, J.D. The family antecedents and the subsequent outcomes of early puberty. J. Youth Adolesc. 2011, 40, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice, P.; Viner, R.M. Pubertal timing and adult obesity and cardiometabolic risk in women and men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biro, F.M.; Greenspan, L.C.; Galvez, M.P.; Pinney, S.M.; Teitelbaum, S.; Windham, G.C.; Deardorff, J.; Herrick, R.L.; Succop, P.A.; Hiatt, R.A.; et al. Onset of breast development in a longitudinal cohort. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juul, F.; Chang, V.W.; Brar, P.; Parekh, N. Birth weight, early life weight gain and age at menarche: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 1272–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biro, F.M.; Khoury, P.; Morrison, J.A. Influence of obesity on timing of puberty. Int. J. Androl. 2006, 29, 272–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.L.; Fu, J.F.; Liang, L.; Gong, C.X.; Xiong, F.; Luo, F.H.; Liu, G.L.; Chen, S.K. Association between obesity and sexual maturation in Chinese children: A muticenter study. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 1312–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.; Santos, P.; Duarte, J.; Mota, J. Association between overweight and early sexual maturation in Portuguese boys and girls. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2006, 33, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Is obesity associated with early sexual maturation? A comparison of the association in American boys versus girls. Pediatrics 2002, 110, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suglia, S.F.; Duarte, C.S.; Chambers, E.C.; Boynton-Jarrett, R. Cumulative social risk and obesity in early childhood. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e1173–e1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleil, M.E.; Spieker, S.J.; Gregorich, S.E.; Thomas, A.S.; Hiatt, R.A.; Appelhans, B.M.; Roisman, G.I.; Booth-LaForce, C. Early Life Adversity and Pubertal Timing: Implications for Cardiometabolic Health. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2020, 46, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, J.A.; Palma, C.L.; Mellor, D.; Green, J.; Renzaho, A.M.N. The relationship between family functioning and child and adolescent overweight and obesity: A systematic review. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, A.F. Age at puberty and father absence in a national probability sample. J. Adolesc. 2005, 28, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.J.; Essex, M.J. Family environments, adrenarche, and sexual maturation: A longitudinal test of a life history model. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 1799–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, T.E.; Caspi, A.; Belsky, J.; Silva, P.A. Childhood experience and the onset of menarche: A test of a sociobiological model. Child Dev. 1992, 63, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deardorff, J.; Ekwaru, J.P.; Kushi, L.H.; Ellis, B.J.; Greenspan, L.C.; Mirabedi, A.; Landaverde, E.G.; Hiatt, R.A. Father absence, body mass index, and pubertal timing in girls: Differential effects by family income and ethnicity. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 48, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Y. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Early Pubertal Timing Among Girls: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, C.M.; Carroll, M.D.; Fryar, C.D.; Ogden, C.L. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015–2016; NCHS data brief, no 288; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Isasi, C.R.; Rastogi, D.; Molina, K. Health issues in Hispanic/Latino youth. J. Lat./O Psychol. 2016, 4, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradín, C. Poverty among minorities in the United States: Explaining the racial poverty gap for Blacks and Latinos. Appl. Econ. 2012, 44, 3793–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiatt, R.A.; Stewart, S.L.; Hoeft, K.S.; Kushi, L.H.; Windham, G.C.; Biro, F.M.; Pinney, S.M.; Wolff, M.S.; Teitelbaum, S.L.; Braithwaite, D. Childhood Socioeconomic Position and Pubertal Onset in a Cohort of Multiethnic Girls: Implications for Breast Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2017, 26, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James-Todd, T.; Tehranifar, P.; Rich-Edwards, J.; Titievsky, L.; Terry, M.B. The Impact of Socioeconomic Status across Early Life on Age at Menarche Among a Racially Diverse Population of Girls. Ann. Epidemiol. 2010, 20, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basáñez, T.; Dennis, J.M.; Crano, W.; Stacy, A.; Unger, J.B. Measuring Acculturation Gap Conflicts among Hispanics: Implications for Psychosocial and Academic Adjustment. J. Fam. Issues 2014, 35, 1727–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, L.C.; Paniagua-Avila, A.; Hua, S.; Terry, M.B.; McDonald, J.A.; Ulanday, K.T.; van Horn, L.; Carnethon, M.R.; Isasi, C.R. Immigrant generation status and its association with pubertal timing and tempo among Hispanic girls and boys. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2023, 35, e23940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, K.E.; Gerdes, A.C.; Kapke, T. The role of acculturation differences and acculturation conflict in Latino family mental health. J. Lat./O Psychol. 2018, 6, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biro, F.M.; Galvez, M.P.; Greenspan, L.C.; Succop, P.A.; Vangeepuram, N.; Pinney, S.M.; Teitelbaum, S.; Windham, G.C.; Kushi, L.H.; Wolff, M.S. Pubertal Assessment Method and Baseline Characteristics in a Mixed Longitudinal Study of Girls. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e583–e590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyt, L.T.; Niu, L.; Pachucki, M.C.; Chaku, N. Timing of puberty in boys and girls: Implications for population health. SSM—Popul. Health 2020, 10, 100549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Styne, D. Influences on the onset and tempo of puberty in human beings and implications for adolescent psychological development. Horm. Behav. 2013, 64, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.; Ruiz, M.O.; Rovnaghi, C.R.; Tam, G.K.Y.; Hiscox, J.; Gotlib, I.H.; Barr, D.A.; Carrion, V.G.; Anand, K.J.S. The social ecology of childhood and early life adversity. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 89, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.T.; DiLalla, L.F.; Corley, R.P.; Dorn, L.D.; Berenbaum, S.A. Family environmental antecedents of pubertal timing in girls and boys: A review and open questions. Horm. Behav. 2022, 138, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, Y.V.; Sanchez, S.E.; Nicolaidis, C.; Garcia, P.J.; Gelaye, B.; Zhong, Q.; Williams, M.A. Childhood abuse and early menarche among Peruvian women. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suglia, S.F.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Cammack, A.L.; April-Sanders, A.K.; McGlinchey, E.L.; Kubo, A.; Bird, H.; Canino, G.; Duarte, C.S. Childhood Adversity and Pubertal Development Among Puerto Rican Boys and Girls. Psychosom. Med. 2020, 82, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, J.; Reeves, J.W.; Hyland, C.; Tilles, S.; Rauch, S.; Kogut, K.; Greenspan, L.C.; Shirtcliff, E.; Lustig, R.H.; Eskenazi, B.; et al. Childhood Overweight and Obesity and Pubertal Onset Among Mexican-American Boys and Girls in the CHAMACOS Longitudinal Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 191, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birman, D. Measurement of the “Acculturation Gap” in Immigrant Families and Implications for Parent-Child Relationships. In Acculturation and Parent-Child Relationships: Measurement and Development; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik, J.; Kurtines, W.M. Family psychology and cultural diversity: Opportunities for theory, research, and application. Am. Psychol. 1993, 48, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavange, L.M.; Kalsbeek, W.D.; Sorlie, P.D.; Aviles-Santa, L.M.; Kaplan, R.C.; Barnhart, J.; Liu, K.; Giachello, A.; Lee, D.J.; Ryan, J.; et al. Sample design and cohort selection in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann. Epidemiol. 2010, 20, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorlie, P.D.; Aviles-Santa, L.M.; Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; Kaplan, R.C.; Daviglus, M.L.; Giachello, A.L.; Schneiderman, N.; Raij, L.; Talavera, G.; Allison, M.; et al. Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann. Epidemiol. 2010, 20, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isasi, C.R.; Carnethon, M.R.; Ayala, G.X.; Arredondo, E.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Daviglus, M.L.; Delamater, A.M.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Perreira, K.; Himes, J.H.; et al. The Hispanic Community Children’s Health Study/Study of Latino Youth (SOL Youth): Design, objectives, and procedures. Ann. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, L.C.; Roesch, S.C.; Bravin, J.I.; Savin, K.L.; Perreira, K.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; Delamater, A.M.; Salazar, C.R.; Lopez-Gurrola, M.; Isasi, C.R. Socioeconomic Adversity, Social Resources, and Allostatic Load Among Hispanic/Latino Youth: The Study of Latino Youth. Psychosom. Med. 2019, 81, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, N.B.; Baldwin, L.M.; Bishop, D.S. The McMASTER Family Assessment Device*. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 1983, 9, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabacoff, R.I.; Miller, I.W.; Bishop, D.S.; Epstein, N.B.; Keitner, G.I. A psychometric study of the McMaster Family Assessment Device in psychiatric, medical, and nonclinical samples. J. Fam. Psychol. 1990, 3, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.W.; Epstein, N.B.; Bishop, D.S.; Keitner, G.I. The McMASTER Family Assessment Device: Reliablity and Validity*. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 1985, 11, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.; Henriksen, L.; Foshee, V.A. The Authoritative Parenting Index: Predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents. Health Educ. Behav. 1998, 25, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Wilson, C.; Slater, A.; Mohr, P. Parent- and child-reported parenting. Associations with child weight-related outcomes. Appetite 2011, 57, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, A.C.; Crockett, L.; Richards, M.; Boxer, A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. J. Youth Adolesc. 1988, 17, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, W.A.; Tanner, J.M. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch. Dis. Child. 1969, 44, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, W.A.; Tanner, J.M. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch. Dis. Child. 1970, 45, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, L.; Clements, J.; Bertalli, N.; Evans-Whipp, T.; McMorris, B.J.; Patton, G.C.; Toumbourou, J.W.; Catalano, R.F. A comparison of self-reported puberty using the Pubertal Development Scale and the Sexual Maturation Scale in a school-based epidemiologic survey. J. Adolesc. 2006, 29, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks-Gunn, J.; Warren, M.P.; Rosso, J.; Gargiulo, J. Validity of self-report measures of girls’ pubertal status. Child Dev. 1987, 58, 829–841. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn, L.D. Measuring puberty. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 39, 625–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Biro, F.M.; Dorn, L.D. Determination of Relative Timing of Pubertal Maturation through Ordinal Logistic Modeling: Evaluation of Growth and Timing Parameters. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, B.; Harrell, F.E., Jr. Partial Proportional Odds Models for Ordinal Response Variables. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C (Appl. Stat.) 1990, 39, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boynton-Jarrett, R.; Wright, R.J.; Putnam, F.W.; Lividoti Hibert, E.; Michels, K.B.; Forman, M.R.; Rich-Edwards, J. Childhood abuse and age at menarche. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, J.G.; Trickett, P.K.; Long, J.D.; Negriff, S.; Susman, E.J.; Shalev, I.; Li, J.C.; Putnam, F.W. Childhood Sexual Abuse and Early Timing of Puberty. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 60, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- April-Sanders, A.K.; Tehranifar, P.; Argov, E.L.; Suglia, S.F.; Rodriguez, C.B.; McDonald, J.A. Influence of Childhood Adversity and Infection on Timing of Menarche in a Multiethnic Sample of Women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, B.J.; Sheridan, M.A.; Belsky, J.; McLaughlin, K.A. Why and how does early adversity influence development? Toward an integrated model of dimensions of environmental experience. Dev. Psychopathol. 2022, 34, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Sheridan, M.A. Beyond Cumulative Risk:A Dimensional Approach to Childhood Adversity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 25, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Sheridan, M.A.; Humphreys, K.L.; Belsky, J.; Ellis, B.J. The Value of Dimensional Models of Early Experience: Thinking Clearly About Concepts and Categories. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 16, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Weissman, D.G.; Flournoy, J. Challenges with Latent Variable Approaches to Operationalizing Dimensions of Childhood adversity—A Commentary on Sisitsky et al. (2023). Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2023, 51, 1809–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousikou, M.; Kyriakou, A.; Skordis, N. Stress and Growth in Children and Adolescents. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2023, 96, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Reid, B.M.; Donzella, B.; Miller, B.S.; Gunnar, M.R. Early-life stress and current stress predict BMI and height growth trajectories in puberty. Dev. Psychobiol. 2022, 64, e22342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S.M.; Bartley, M.J.; Wilkinson, R.G. Family conflict and slow growth. Arch. Dis. Child. 1997, 77, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abajobir, A.A.; Kisely, S.; Williams, G.; Strathearn, L.; Najman, J.M. Height deficit in early adulthood following substantiated childhood maltreatment: A birth cohort study. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 64, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epel, E.S. Psychological and metabolic stress: A recipe for accelerated cellular aging? Hormones 2009, 8, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, D.; Viner, R. Adolescent development. BMJ 2005, 330, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulanicka, B.; Gronkiewicz, L.; Koniarek, J. Effect of familial distress on growth and maturation of girls: A longitudinal study. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2001, 13, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleil, M.E.; Booth-LaForce, C.; Benner, A.D. Race Disparities in Pubertal Timing: Implications for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among African American Women. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2017, 36, 717–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Denholm, R.; Power, C. Child maltreatment and household dysfunction: Associations with pubertal development in a British birth cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wroblewski, E.E.; Murray, C.M.; Keele, B.F.; Schumacher-Stankey, J.C.; Hahn, B.H.; Pusey, A.E. Male dominance rank and reproductive success in chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii. Anim. Behav. 2009, 77, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, S.B.Z.; Wallen, K. Environmental and social influences on neuroendocrine puberty and behavior in macaques and other nonhuman primates. Horm. Behav. 2013, 64, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushannen, T.; Cortez, P.; Stanford, F.C.; Singhal, V. Obesity and Hypogonadism-A Narrative Review Highlighting the Need for High-Quality Data in Adolescents. Children 2019, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, A.A.; Holdsworth, E.; Ryan, M.; Tracy, M. Measuring Childhood Adversity in Life Course Cardiovascular Research: A Systematic Review. Psychosom. Med. 2017, 79, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirtcliff, E.A.; Dahl, R.E.; Pollak, S.D. Pubertal development: Correspondence between hormonal and physical development. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfahrt-Veje, C.; Mouritsen, A.; Hagen, C.P.; Tinggaard, J.; Mieritz, M.G.; Boas, M.; Petersen, J.H.; Skakkebæk, N.E.; Main, K.M. Pubertal Onset in Boys and Girls Is Influenced by Pubertal Timing of Both Parents. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 2667–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, T.N.; Killen, J.D.; Litt, I.F.; Hammer, L.D.; Wilson, D.M.; Haydel, K.F.; Hayward, C.; Taylor, C.B. Ethnicity and body dissatisfaction: Are Hispanic and Asian girls at increased risk for eating disorders? J. Adolesc. Health 1996, 19, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, J.M.; Yancey, A.K.; Aneshensel, C.S.; Schuler, R. Body image, perceived pubertal timing, and adolescent mental health. J. Adolesc. Health 1999, 25, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, A.; Shmoish, M.; Hochberg, Z.e. Predicting pubertal development by infantile and childhood height, BMI, and adiposity rebound. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 78, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, R.M.B.; Deardorff, J.; Gonzales, N.A. Contextual Amplification or Attenuation of Pubertal Timing Effects on Depressive Symptoms Among Mexican American Girls. J. Adolesc. Health 2012, 50, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhail, M.E.; Carroll, S.L.; Clark, D.A.; O’Connor, S.; Burt, S.A.; Klump, K.L. Context matters: Neighborhood disadvantage is associated with increased disordered eating and earlier activation of genetic influences in girls. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2021, 130, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Boys n = 728 | Girls n = 738 | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Age at Interview | 12.1 ± 0.1 | 12.1 ± 0.1 |

| Language Administered | ||

| English | 552 (80.0) | 563 (81.0) |

| Spanish | 123 (20.0) | 125 (19.0) |

| Hispanic/Latino background | ||

| Dominican | 83 (13.4) | 84 (13.4) |

| Puerto Rican | 64 (10.1) | 64 (9.7) |

| Cuban | 53 (5.3) | 50 (6.0) |

| Central American | 45 (5.0) | 67 (7.7) |

| Mexican | 312 (49.6) | 336 (47.6) |

| South American | 38 (4.5) | 30 (3.8) |

| Mixed Hispanic | 68 (10.1) | 67 (10.0) |

| Other | 13 (1.9) | 12 (1.8) |

| Nativity | ||

| Non-US mainland born | 165 (22.0) | 161 (21.9) |

| US mainland born | 556 (78.0) | 572 (78.1) |

| Family Socioeconomic Characteristics (parent-report) | ||

| Household income less than USD 30,000 | 517 (72.2) | 514 (69.4) |

| Less than high school or equivalent, caregiver | 279 (37.6) | 286 (39.7) |

| Unemployment, caregiver(s) | 315 (44.5) | 321 (45.6) |

| Child Body Size | ||

| BMI percentile | 72.5 ± 1.5 | 72.5 ± 1.4 |

| Obesity (BMI percentile ≥ 95th percentile) | 230 (28.6) | 182 (24.8) |

| Boys | Girls | |

|---|---|---|

| Puberty Indicators | ||

| Growth in height, (Boys n = 563) (Girls n = 562) | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

| 1. Has not yet begun to spurt. | 89 (13.4) | 53 (9.5) |

| 2. Has barely started. | 142 (25.5) | 130 (20.2) |

| 3. Is definitely underway. | 245 (43.0) | 204 (35.6) |

| 4. Seems completed. | 87 (18.0) | 175 (34.7) |

| Growth in hair, (Boys n = 646) (Girls n = 651) | 2.6 ± 0.04 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| 1. Has not yet begun to grow. | 116 (16.5) | 96 (12.7) |

| 2. Has barely started growing. | 154 (22.8) | 132 (18.9) |

| 3. Is definitely underway. | 263 (40.7) | 216 (30.6) |

| 4. Seems completed. | 113 (20.0) | 207 (37.8) |

| Skin changes, (Boys n = 662) (Girls n = 663) | 2.3 ± 0.04 | 2.5 ± 0.04 |

| 1. Skin has not yet started changing. | 209 (30.0) | 161 (23.9) |

| 2. Skin has barely started changing. | 173 (23.5) | 142 (20.1) |

| 3. Skin changes are definitely underway. | 212 (36.9) | 265 (38.0) |

| 4. Skin changes seem complete. | 68 (9.6) | 95 (18.1) |

| Deepening of voice, (Boys n = 672) | 2.4 ± 0.1 | . |

| 1. Voice has not yet started changing. | 209 (27.1) | . |

| 2. Voice has barely started changing. | 174 (24.4) | . |

| 3. Voice changes are definitely underway. | 192 (32.6) | . |

| 4. Voice changes seem complete. | 97 (15.9) | . |

| Hair growing on face, (Boys n = 660) | 2.0 ± 0.04 | . |

| 1. Facial hair has not started growing. | 281 (40.4) | . |

| 2. Facial hair has barely started growing. | 195 (30.5) | . |

| 3. Facial hair growth has definitely started. | 149 (22.2) | . |

| 4. Facial hair growth seems complete. | 35 (6.8) | . |

| Breast growth, (Girls n = 657) | . | 2.6 ± 0.04 |

| 1. Have not yet started growing. | . | 96 (14.3) |

| 2. Have barely started growing. | . | 172 (25.6) |

| 3. Breast growth is definitely underway. | . | 296 (45.1) |

| 4. Breast growth seems complete. | . | 93 (15.0) |

| Menstruation, (Girls n = 722) | . | 2.7 ± 0.1 |

| 1. No | . | 324 (43.1) |

| 2. Yes | . | 398 (56.9) |

| Age at menarche, (Girls n = 391) | . | 11.3 ± 0.1 |

| Models Among Boys | Growth in Height (n = 545) | Body Hair Growth (n = 621) | Skin Changes (n = 635) | Voice Deepening (n = 649) | Facial Hair Growth (n = 638) | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Family dysfunction | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0.68 (0.43, 1.07) | 0.90 (0.60, 1.34) | 1.12 (0.79, 1.58) | 0.77 (0.52, 1.14) | 1.03 (0.66, 1.59) | |

| Model 2 | 0.68 (0.44, 1.05) | 0.91 (0.62, 1.35) | 1.08 (0.77, 1.52) | 0.79 (0.53, 1.16) | 1.05 (0.67, 1.64) | |

| Model 3 | 0.68 (0.43, 1.05) | 0.92 (0.62, 1.37) | 1.07 (0.76, 1.51) | 0.79 (0.53, 1.16) | 1.06 (0.67, 1.68) | |

| Model 4 | 0.66 (0.43, 1.03) | 0.90 (0.61, 1.34) | 1.06 (0.75, 1.50) | 0.79 (0.54, 1.17) | 1.04 (0.66, 1.64) | |

| Models Among Girls | Growth in height (n = 549) | Body hair growth (n = 632) | Skin changes (n = 644) | Breast growth (n = 634) | Onset of menses (n = 699) | Age at menarche (n = 381) |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | |

| Family dysfunction | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0.69 (0.47, 1.02) | 0.83 (0.55, 1.23) | 0.84 (0.58, 1.22) | 0.85 (0.57, 1.28) | 1.22 (0.58, 2.59) | −0.09 (−0.44, 0.27) |

| Model 2 | 0.70 (0.47, 1.03) | 0.90 (0.60, 1.35) | 0.84 (0.57, 1.24) | 0.85 (0.56, 1.28) | 1.24 (0.53, 2.86) | −0.16 (−0.52, 0.19) |

| Model 3 | 0.61 (0.40, 0.93) * | 0.91 (0.60, 1.39) | 0.81 (0.56, 1.19) | 0.88 (0.59, 1.33) | 1.28 (0.58, 2.79) | −0.18 (−0.53, 0.17) |

| Model 4 | 0.60 (0.39, 0.90) * | 0.91 (0.59, 1.38) | 0.77 (0.53, 1.13) | 0.85 (0.57, 1.27) | 1.24 (0.57, 2.70) | −0.15 (−0.50, 0.20) |

| Models | Boys (n = 473) | Girls (n = 472) |

|---|---|---|

| b (95% CI) | b (95% CI) | |

| Puberty score, M (SE) | 12.20 (0.22) | 14.19 (0.23) |

| Family dysfunction | ||

| Model 1 | −0.60 (−1.21, 0.005) | −0.32 (−0.92, 0.28) |

| Model 2 | −0.63 (−1.21, −0.04) * | −0.31 (−0.91, 0.29) |

| Model 3 | −0.65 (−1.22, −0.07) * | −0.32 (−0.89, 0.25) |

| Model 4 | −0.65 (−1.21, −0.10) * | −0.34 (−0.89, 0.22) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

April-Sanders, A.K.; Tehranifar, P.; Terry, M.B.; Crookes, D.M.; Isasi, C.R.; Gallo, L.C.; Fernandez-Rhodes, L.; Perreira, K.M.; Daviglus, M.L.; Suglia, S.F. Family Functioning and Pubertal Maturation in Hispanic/Latino Children from the HCHS/SOL Youth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040576

April-Sanders AK, Tehranifar P, Terry MB, Crookes DM, Isasi CR, Gallo LC, Fernandez-Rhodes L, Perreira KM, Daviglus ML, Suglia SF. Family Functioning and Pubertal Maturation in Hispanic/Latino Children from the HCHS/SOL Youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040576

Chicago/Turabian StyleApril-Sanders, Ayana K., Parisa Tehranifar, Mary Beth Terry, Danielle M. Crookes, Carmen R. Isasi, Linda C. Gallo, Lindsay Fernandez-Rhodes, Krista M. Perreira, Martha L. Daviglus, and Shakira F. Suglia. 2025. "Family Functioning and Pubertal Maturation in Hispanic/Latino Children from the HCHS/SOL Youth" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040576

APA StyleApril-Sanders, A. K., Tehranifar, P., Terry, M. B., Crookes, D. M., Isasi, C. R., Gallo, L. C., Fernandez-Rhodes, L., Perreira, K. M., Daviglus, M. L., & Suglia, S. F. (2025). Family Functioning and Pubertal Maturation in Hispanic/Latino Children from the HCHS/SOL Youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 576. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040576