Evaluating the Uptake of the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) B701:17 (R2021) Carer-Inclusive and Accommodating Organizations Standard Across Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Gender and Equity

1.2. Workplace Culture

1.3. COVID-19 Pandemic and Demographic Shifts

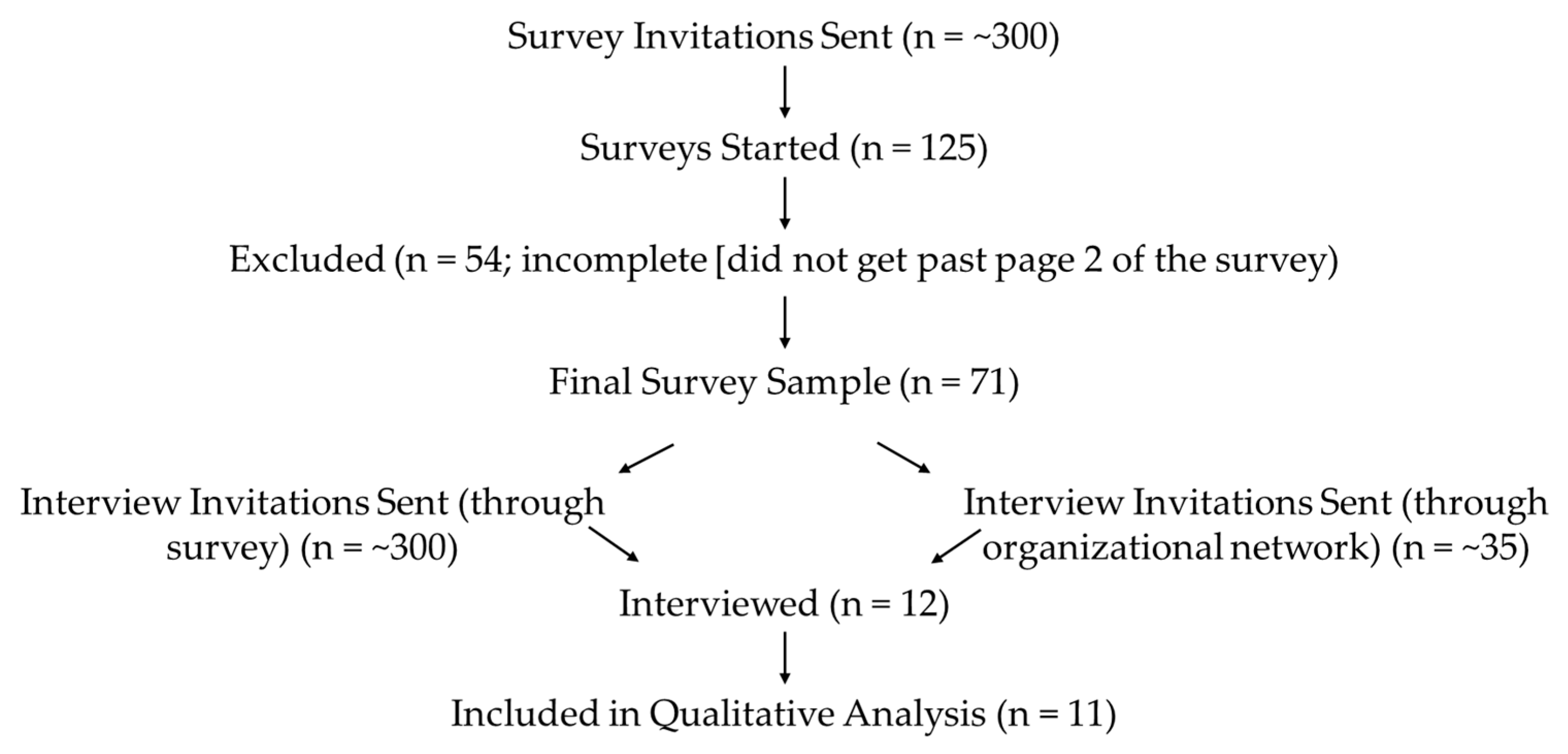

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Logistic Regression Modelling

3.3. Thematic Findings

3.4. Workplace Culture

3.4.1. Communication

3.4.2. Self-Identification

3.4.3. Employee Accountability

3.4.4. Demographics

3.5. Current Employee Supports

3.5.1. Umbrella Policies

3.5.2. Informal Support/Case-by-Case

3.5.3. Flexibility

3.5.4. Emotional Support

3.5.5. Measurement and Feedback

3.6. Barriers to Uptake

3.6.1. Spatiotemporal Constraints

3.6.2. C-Suite Disconnect

3.6.3. Access to HR

3.6.4. Standard Navigation

3.7. Facilitators to Uptake

3.7.1. Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI)

3.7.2. Unions

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CE | Carer-employee |

| CFWPs | Carer-friendly workplace practices |

| HR | Human Resources |

| CSA | Canadian Standards Association |

References

- Raco, M. Building Sustainable Communities: Spatial Policy and Labour Mobility in Post-War Britain Building Sustainable Communities; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2007; pp. 167–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lilly, M.B.; Laporte, A.; Coyte, P.C. Do they care too much to work? The influence of caregiving intensity on the labour force participation of unpaid caregivers in Canada. J. Health Econ. 2010, 29, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, N. Ethics, Health Research, and Canada’s Aging Population. Can. J. Aging La Rev. Can. Du Vieil. 2010, 29, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decady, Y.; Greenberg, L. Ninety Years of Change in Life Expectancy; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Canada’s Fertility Rate Reaches an All-Time Low in 2022; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024.

- Eisen, B.; Emes, J. Understanding the Changing Ratio of Working-Age Canadians to Seniors and Its Consequences; Fraser Institute: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ireson, R.; Sethi, B.; Williams, A. Availability of caregiver-friendly workplace policies (CFWPs): An international scoping review. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 26, e1–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Williams, A.; Wang, L.; Kitchen, P. A comparative analysis of carer-employees in Canada over time: A cross-sectional analysis of Canada’s General Social Survey, 2012 and 2018. Can. J. Public Health 2023, 114, 840–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaye, A.; Kim, C.; Eales, J.; Fast, J. Employed Caregivers in Canada: Infographic Series Based on Analyses of Statistics Canada’s 2018 General Social Survey on Caregiving and Care Receiving Research on Aging, Policies and Practice Department of Human Ecology; University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, J. This is What Canada will Look like in 20 Years—Are We Ready for an Aging Population? 2023. Available online: https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/this-is-what-canada-will-look-like-in-20-years-are-we-ready-for-an-aging-population-1.6652355#:~:text=Residents%20aged%2065%20and%20older,65%20and%20older%20in%20Canada (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Statistics Canada. Census of Population; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021.

- Wu, J.; Williams, A.; Wang, L.; Henningsen, N.; Kitchen, P. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on carer-employees’ well-being: A twelve-country comparison. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2023, 4, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CSA B701:17; Carer-Inclusive and Accommodating Organizations Standard. Canadian Standards Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017.

- Canadian Standards Association. Helping Worker Carers in Your Organization; Canadian Standards Association: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, F.; Whittaker, L.; Tazzeo, J.; Williams, A. Availability of caregiver-friendly workplace policies: An international scoping review follow-up study. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2021, 14, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Dardas, A.; Wang, L.; Williams, A. Evaluation of a Caregiver-Friendly Workplace Program Intervention on the Health of Full-Time Caregiver Employees: A Time Series Analysis of Intervention Effects. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, e548–e558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Williams, A.; Kitchen, P. Health of caregiver-employees in Canada. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2018, 11, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Dardas, A.; Wang, L.; Williams, A. Improving the Workplace Experience of Caregiver-Employees: A Time-Series Analysis of a Workplace Intervention. Saf. Health Work 2021, 12, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Gafni, A.; Williams, A. Cost Implications from an Employer Perspective of a Workplace Intervention for Carer-Employees during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofidi, A.; Tompa, E.; Williams, A.; Yazdani, A.; Lero, D.; Mortazavi, S.B. Impact of a Caregiver-Friendly Workplace Policies Intervention: A Prospective Economic Evaluation. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobel, J.; Weiss, J.; Sasser, E.; Sherman, C.; Pickering, L. The Caregiving Landscape: Challenges and Opportunities for Employers. J. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017. Available online: https://nebgh.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NEBGH-CaregivingLandscape-FINAL-web.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Phillips, D.; Paul, G.; Fahy, M.; Dowling-Hetherington, L.; Kroll, T.; Moloney, B.; Duffy, C.; Fealy, G.; Lafferty, A. The invisible workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: Family carers at the frontline. HRB Open Res. 2020, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, M. How the Pandemic Made ‘Caregiver’ the Newest Workplace Identity; TIME: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Loomis, L.; Booth, A. Multigenerational Caregiving and Well-Being: The Myth of the Beleaguered Sandwich Generation. J. Fam. Issues 1995, 16, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medjuck, S.; Keefe, J.M.; Fancey, P.J. Available But Not Accessible: An Examination of the Use of Workplace Policies for Caregivers of Elderly Kin. J. Fam. Issues 1998, 19, 274–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowska-Kmon, A.; Ronald, J.B.; Lisa, M.C. (Eds.) The Sandwich Generation. Caring for Oneself and Others at Home and at Work. Eur. J. Popul. 2018, 34, 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A.M.; Tompa, E.; Lero, D.S.; Fast, J.; Yazdani, A.; Zeytinoglu, I.U. Evaluation of caregiver-friendly workplace policy (CFWPs) interventions on the health of full-time caregiver employees (CEs): Implementation and cost-benefit analysis. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, R.Y.; Williams, A.M. Places of paid work and unpaid work: Caregiving and work-from-home during COVID-19. Can. Geogr./Géographies Can. 2022, 66, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Williams, A. The Role of Carer-Friendly Workplace Policies and Social Support in Relation to the Mental Health of Carer-Employees. Health Soc. Care Community 2023, 2023, 5749542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.M.; Cawley, C.; Williams, A.; Mustard, C. Male/female differences in the impact of caring for elderly relatives on labor market attachment and hours of work: 1997–2015. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2020, 75, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. More than Half of Women Provide Care to Children and Care-Dependent Adults in Canada, 2022; Statistics Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221108/dq221108b-eng.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Statistics Canada. Surveys and Statistical Programs—General Social Survey (GSS)—Caregiving and Care Receiving; Statistics Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=4502 (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Crooks, V.A.; Williams, A. An evaluation of Canada’s Compassionate Care Benefit from a family caregiver’s perspective at end of life. BMC Palliat. Care 2008, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flagler, J.; Dong, W. The uncompassionate elements of the Compassionate Care Benefits Program: A critical analysis. Glob Health Promot. 2010, 17, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.M.; Eby, J.A.; Crooks, V.A.; Stajduhar, K.; Giesbrecht, M.; Vuksan, M.; Cohen, S.R.; Brazil, K.; Allan, D. Canada’s Compassionate Care Benefit: Is it an adequate public health response to addressing the issue of caregiver burden in end-of-life care? BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lero, D.S.; Spinks, N.; Fast, J.; Hilbrecht, M.; Tremblay, D.-G. The Availability, Accessibility and Effectiveness of Workplace Supports for Canadian Caregivers: Centre for Families, Work & Well-Being; University of Guelph: Guelph, On, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, S.; Ireson, R.; Williams, A. International synthesis and case study examination of promising caregiver-friendly workplaces. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 177, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blight, A.C. The Role Identity of Caregivers: A Quantitative Study of Relational and Organizational Identification, Dirty Work and the Self; Washington University: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Business Group on Health. Caregiving Survey 2020. Available online: https://online.flippingbook.com/view/907037/8/#zoom=true (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Wang, L.; Ji, C.; Kitchen, P.; Williams, A. Social participation and depressive symptoms of carer-employees of older adults in Canada: A cross-sectional analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Can. J. Public Health 2021, 112, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Seniors in Need, Caregivers in Distres: What Are the Home Care Priorities for Seniors in Canada? Statistics Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012.

- Sinha, M. Portrait of Caregivers; Statistics Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Seniors; Statistics Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-402-x/2011000/chap/seniors-aines/seniors-aines-eng.htm (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Bal, M.; Stok, M.; Kamphuis, C.; Bos, J.; Hoogenboom, M.; de Wit, J.; Yerkes, M.A. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Societal Challenges to Solidarity and Social Justicesocial justice: Consequences for Vulnerable Groups. In Solidarity and Social Justice in Contemporary Societies: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Understanding Inequalities; Yerkes, M.A., Bal, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, X.W.; Shang, S.; Brough, P.; Wilkinson, A.; Lu, C.-Q. Work, life and COVID-19: A rapid review and practical recommendations for the post-pandemic workplace. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2023, 61, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirmohammadi, M.; Chan, A.W.; Beigi, M. Remote work and work-life balance: Lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic and suggestions for HRD practitioners. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2022, 25, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, C.; Sehgal, S. (Eds.) Sentiment Analysis on Product Reviews. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Computing, Communication and Automation (ICCCA), Greater Noida, India, 5–6 May 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, K. Engaging interviews. Qual. Res. Methods Hum. Geogr. 2021, 5, 148–185. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, K. Why Men Can (and Should) Participate in the Care Economy Too. 2022. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/08/care-economy-industry-gender-equity/ (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Alvarez-Roldan, A.; Bravo-González, F. Masculinity in Caregiving: Impact on Quality of Life and Self-Stigma in Caregivers of People with Multiple Sclerosis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, K.; Williams, A.; Chloe, I. Male working carers: A qualitative analysis of males involved in caring alongside full-time paid work. Int. J. Care Caring 2019, 3, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. Other Countries’ Experiences with Caregiver Policies; United States Government Accountability Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/assets/720/710165.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Dardas, A.; Williams, A.; Wang, L. Evaluating changes in workplace culture: Effectiveness of a caregiver-friendly workplace program in a public post-secondary educational institution. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Freq. | % | Std_Dev |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is your workplace sector? | |||

| Healthcare | 28 | 40 | 48.99 |

| Education | 19 | 27.14 | 44.47 |

| Mining/Primary Resource | 2 | 2.86 | 16.67 |

| Transportation | 2 | 2.86 | 16.67 |

| Engineering | 1 | 1.43 | 11.87 |

| Manufacturing | 1 | 1.43 | 11.87 |

| Agriculture | 1 | 1.43 | 11.87 |

| Communications | 1 | 1.43 | 11.87 |

| Construction | 1 | 1.43 | 11.87 |

| Other | 14 | 20 | 40 |

| What is your workplace size? | |||

| 1–99 | 28 | 39.44 | 48.87 |

| 100–499 | 15 | 21.13 | 40.82 |

| 500+ | 28 | 39.44 | 48.87 |

| How long have you worked at this organization? | |||

| Less than 1 year | 10 | 14.08 | 34.78 |

| 1 to 4 years | 27 | 38.03 | 48.55 |

| 5+ years | 34 | 47.89 | 49.96 |

| How did you hear about the CSA B701 Carer-inclusive and accommodating organizations Standard? | |||

| 19 | 26.76 | 44.27 | |

| Internet searches | 12 | 16.9 | 37.48 |

| Social Media | 12 | 16.9 | 37.48 |

| Newsletter | 6 | 8.45 | 27.81 |

| My organization | 4 | 5.63 | 23.05 |

| Word-of-mouth | 4 | 5.63 | 23.05 |

| Colleague(s) | 2 | 2.82 | 16.55 |

| Employee | 1 | 1.41 | 11.79 |

| Other | 11 | 15.49 | 36.18 |

| Does your organization have a Human Resources department and/or role? | |||

| Yes | 61 | 85.92 | 34.78 |

| No | 10 | 14.08 | 34.78 |

| Is the Carer Standard currently implemented in your workplace? | |||

| Yes | 17 | 23.94 | 42.67 |

| No | 28 | 39.44 | 48.87 |

| Don’t Know | 26 | 36.62 | 48.18 |

| Are there existing workplace supports and or resources for carer employees in your workplace? | |||

| Yes | 30 | 42.25 | 49.4 |

| No | 18 | 25.35 | 43.5 |

| Don’t Know | 23 | 32.39 | 46.8 |

| Have carer employees identified themselves in your workplace? | |||

| Yes | 34 | 47.89 | 49.96 |

| No | 16 | 22.54 | 41.78 |

| Don’t Know | 21 | 29.58 | 45.64 |

| Are you a caregiver and or have you been a caregiver in the past? | |||

| Yes | 55 | 77.46 | 41.78 |

| No | 16 | 22.54 | 41.78 |

| If you answered yes to the previous question, indicate how many hours per week you spend caregiving | |||

| 10–20 h per week | 14 | 19.72 | 39.79 |

| Less than 10 h per week | 16 | 22.54 | 41.78 |

| More than 20 h per week | 41 | 57.75 | 49.4 |

| I and or my workplace has found the Standard useful | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 3 | 4.23 | 20.13 |

| Disagree | 4 | 5.63 | 23.05 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 21 | 29.58 | 45.64 |

| Agree | 26 | 36.62 | 48.18 |

| Strongly Agree | 17 | 23.94 | 42.67 |

| I and or my workplace has found the Handbook useful | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 24 | 33.8 | 47.3 |

| Agree | 24 | 33.8 | 47.3 |

| Strongly Agree | 23 | 32.39 | 46.8 |

| I and or my workplace has found BOTH the Standard and Handbook useful | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 23 | 32.39 | 46.8 |

| Agree | 32 | 45.07 | 49.76 |

| Strongly Agree | 16 | 22.54 | 41.78 |

| My workplace plans to implement the standard | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 2 | 2.82 | 16.55 |

| Disagree | 10 | 14.08 | 34.78 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 19 | 26.76 | 44.27 |

| Agree | 29 | 40.85 | 49.16 |

| Strongly Agree | 11 | 15.49 | 36.18 |

| My workplace has fully implemented the Standard | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 4 | 5.63 | 23.05 |

| Disagree | 21 | 29.58 | 45.64 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 20 | 28.17 | 44.98 |

| Agree | 20 | 28.17 | 44.98 |

| Strongly Agree | 6 | 8.45 | 27.81 |

| My workplace is aware of carer employees | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 6 | 8.45 | 27.81 |

| Disagree | 5 | 7.04 | 25.58 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 11 | 15.49 | 36.18 |

| Agree | 29 | 40.85 | 49.16 |

| Strongly Agree | 20 | 28.17 | 44.98 |

| My workplace promotes an inclusive workplace culture | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 1 | 1.41 | 11.79 |

| Disagree | 9 | 12.68 | 33.27 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 13 | 18.31 | 38.67 |

| Agree | 32 | 45.07 | 49.76 |

| Strongly Agree | 16 | 22.54 | 41.78 |

| My workplace provides accommodation for carer employees | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 9 | 12.68 | 33.27 |

| Disagree | 13 | 18.31 | 38.67 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 10 | 14.08 | 34.78 |

| Agree | 25 | 35.21 | 47.76 |

| Strongly Agree | 14 | 19.72 | 39.79 |

| My workplace values work–life balance | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 1 | 1.41 | 11.79 |

| Disagree | 13 | 18.31 | 38.67 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 11 | 15.49 | 36.18 |

| Agree | 28 | 39.44 | 48.87 |

| Strongly Agree | 18 | 25.35 | 43.5 |

| My workplace offers flexible work arrangements | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 7 | 9.86 | 29.81 |

| Disagree | 9 | 12.68 | 33.27 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 11 | 15.49 | 36.18 |

| Agree | 28 | 39.44 | 48.87 |

| Strongly Agree | 16 | 22.54 | 41.78 |

| My workplace actively seeks out ways to better support its carer employees | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 5 | 7.04 | 25.58 |

| Disagree | 21 | 29.58 | 45.64 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 15 | 21.13 | 40.82 |

| Agree | 24 | 33.8 | 47.3 |

| Strongly Agree | 6 | 8.45 | 27.81 |

| Carer employees feel comfortable identifying themselves in my workplace | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 8 | 11.27 | 31.62 |

| Disagree | 13 | 18.31 | 38.67 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 11 | 15.49 | 36.18 |

| Agree | 26 | 36.62 | 48.18 |

| Strongly Agree | 13 | 18.31 | 38.67 |

| Carer employees feel supported in my organization | |||

| Strongly Disagree | 7 | 9.86 | 29.81 |

| Disagree | 9 | 12.68 | 33.27 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 24 | 33.8 | 47.3 |

| Agree | 20 | 28.17 | 44.98 |

| Strongly Agree | 11 | 15.49 | 36.18 |

| Predictor Variable | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% CI (Lower) | 95% CI (Upper) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard fully implemented in the workplace | 15.8 | 2.76 | 90.4 | 0.0027 |

| Workplace values work–life balance | 4.67 | 0.66 | 33.2 | 0.108 |

| Workplace has supports for CEs | 15.9 | 3.99 | 63.6 | 0.0019 |

| Provides care >20 h per week | 0.25 | 0.04 | 1.53 | 0.108 |

| Macro Theme (n = 4) | Micro Theme (n = 14) |

|---|---|

| Communication |

| Self-Identification | |

| Employee Accountability | |

| Demographics | |

| Umbrella Policies |

| Informal Support/Case-by-Case | |

| Flexibility | |

| Emotional Support | |

| Measurement & Feedback | |

| Spatiotemporal Constraints |

| C-Suite Disconnect | |

| Access to HR | |

| Standard Navigation | |

| Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) |

| Unions |

| Participant | Sector | Organization Type | Gender | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Primary Resource | Emergency Medical Services | F | Canada |

| P2 | Education | ECE | F | Canada |

| P3 | Healthcare | Non-profit (provincial) | F | Canada |

| P4 | Business | Consulting | F | Canada |

| P5 | Business | Human Resources | F | Canada |

| P6 | Healthcare | Research | F | Canada |

| P7 | Business | Union | F | Canada |

| P8 | Healthcare | Public Health | F | Canada |

| P9 | Non-profit | Non-profit (Federal) | F | Canada |

| P10 | Communications | Non-profit (Federal) | F | Canada |

| P11 | Healthcare | Non-profit (provincial) | M | Canada |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chmiel, B.; Williams, A. Evaluating the Uptake of the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) B701:17 (R2021) Carer-Inclusive and Accommodating Organizations Standard Across Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060907

Chmiel B, Williams A. Evaluating the Uptake of the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) B701:17 (R2021) Carer-Inclusive and Accommodating Organizations Standard Across Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(6):907. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060907

Chicago/Turabian StyleChmiel, Brooke, and Allison Williams. 2025. "Evaluating the Uptake of the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) B701:17 (R2021) Carer-Inclusive and Accommodating Organizations Standard Across Canada" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 6: 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060907

APA StyleChmiel, B., & Williams, A. (2025). Evaluating the Uptake of the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) B701:17 (R2021) Carer-Inclusive and Accommodating Organizations Standard Across Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(6), 907. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22060907