Economic Evaluation of Proactive PTSI Mitigation Programs for Public Safety Personnel and Frontline Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Informational Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Selection of Studies

2.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Research Design and Methodology

3.3. Intervention Types and Objectives

3.4. Variation in Intervention Design

3.5. Cost Variability Across Interventions

3.6. Effectiveness Measures and Outcomes

3.7. Financial and Economic Evaluations

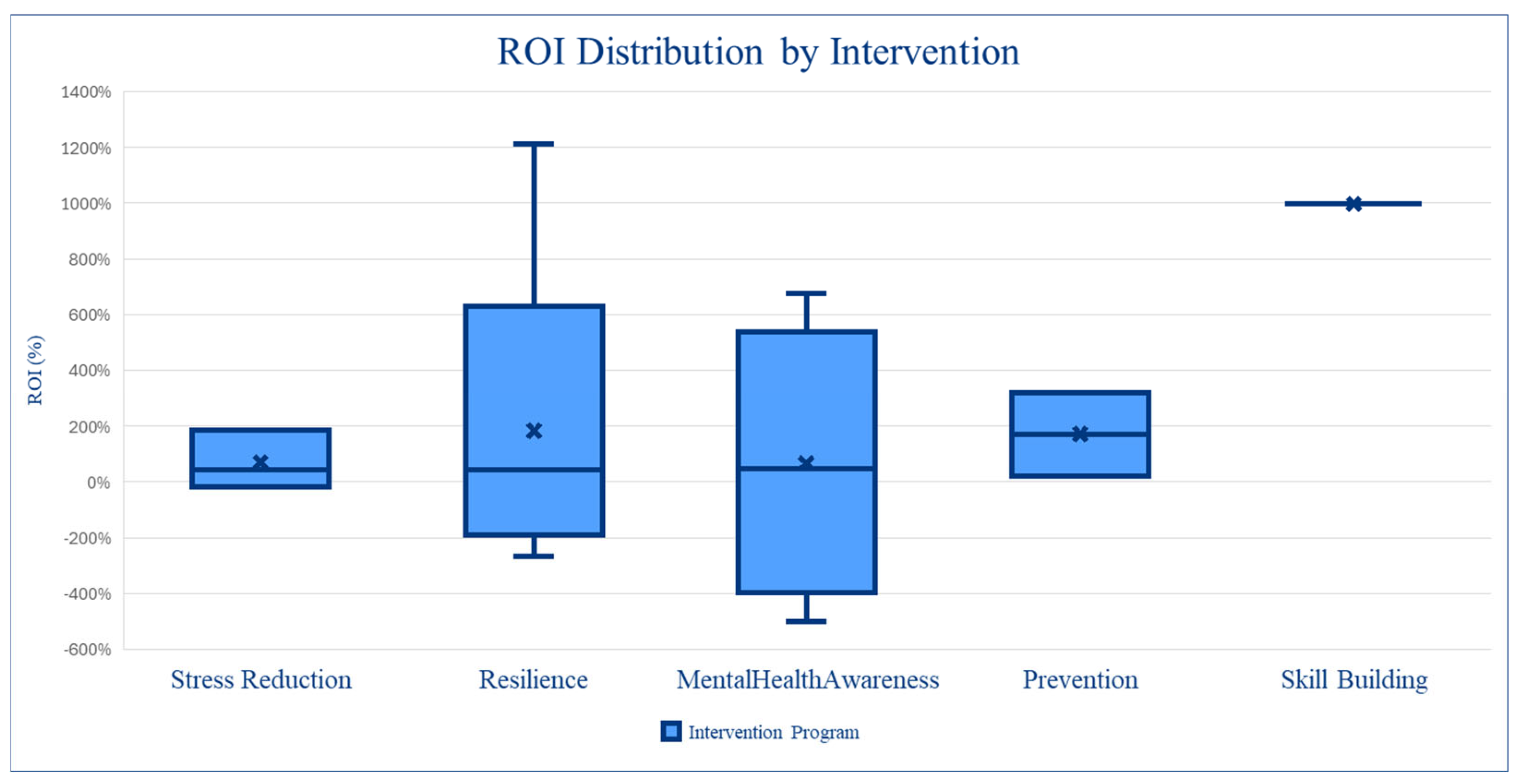

3.8. Sensitivity Analysis and Variability in Outcomes

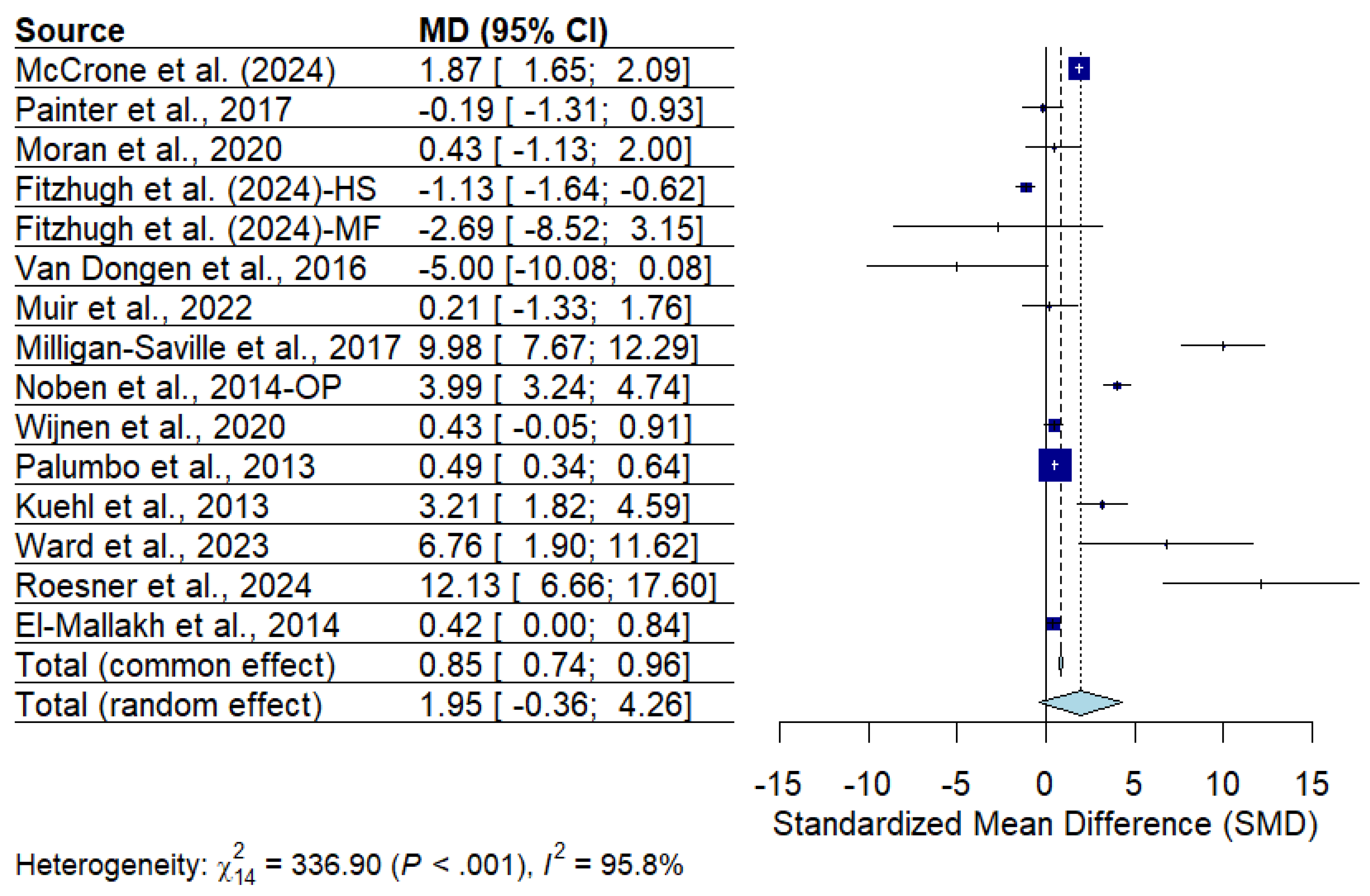

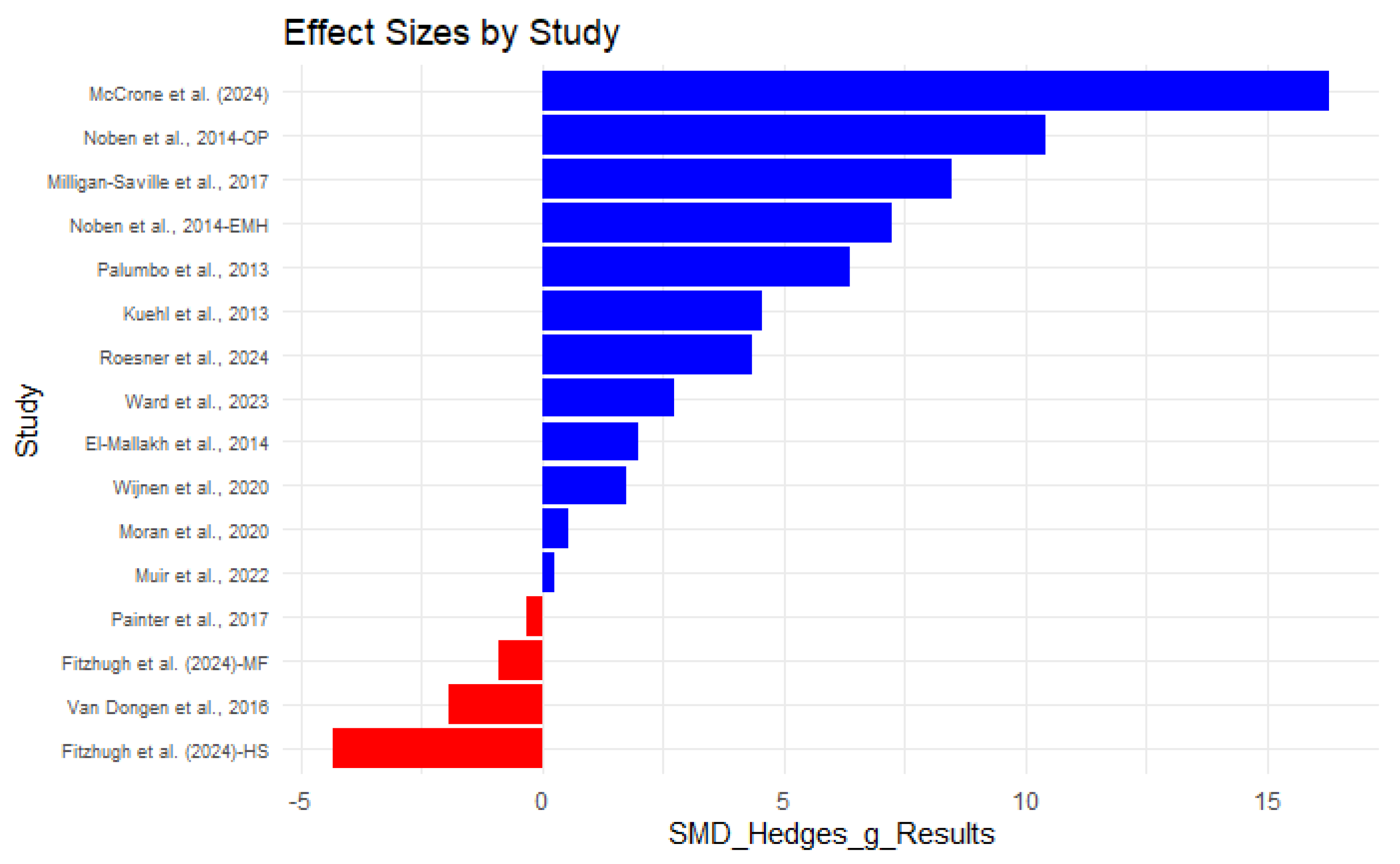

3.9. Assessment of Heterogeneity and Synthesis of Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBI | Copenhagen Burnout Index |

| CBR | Cost–Benefit Ratio |

| CER | Cost-Effectiveness Ratio |

| CIT | Crisis Intervention Team |

| FHP | Frontline Healthcare professionals |

| ICER | Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio |

| ITT | Intent-To-Treat |

| NICE | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| NMB | Net Monetary Benefits |

| OP | Occupational Physician |

| PHLAME | Promoting Healthy Lifestyles: Alternative Models’ Effects |

| PSP | Peer Support Program |

| PSP | Public Safety Personnel |

| PTSI | Post-traumatic Stress Injury |

| PPTE | Potentially Psychologically Traumatic Events |

| QALYs | Quality-Adjusted Life Years |

| QWB | Quality Of Well-Being Scale |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RISE | Resilience In Stressful Events |

| ROI | Return On Investment |

| SDS | Sheehan Disability Scale |

| WF | Work Functioning |

| W/C | Work Capability |

| WC | Workers’ Compensation |

References

- Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment (CIPSRT). Glossary of Terms: A Shared Understanding of the Common Terms Used to Describe Psychological Trauma (Version 2.0). 2019. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10294/9055 (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Carleton, R.N.; Afifi, T.O.; Taillieu, T.; Turner, S.; Krakauer, R.; Anderson, G.S.; MacPhee, R.S.; Ricciardelli, R.; Cramm, H.A.; Groll, D.; et al. Exposures to potentially traumatic events among public safety personnel in Canada. Can. J. Behav. Sci. Rev. Can. Des Sci. Comport. 2019, 51, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nota, P.M.; Bahji, A.; Groll, D.; Carleton, R.N.; Anderson, G.S. Proactive psychological programs designed to mitigate posttraumatic stress injuries among at-risk workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, D.; Wu, A.W.; Connors, C.; Chappidi, M.R.; Sreedhara, S.K.; Selter, J.H.; Padula, W.V. Cost-benefit analysis of a support program for nursing staff. J. Patient Saf. 2020, 16, e250–e254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesner, H.; Neusius, T.; Strametz, R.; Mira, J.J. Economic value of peer support program in German hospitals. Int. J. Public Health 2024, 69, 1607218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mallakh, P.L.; Kiran, K.; El-Mallakh, R.S. Costs and savings associated with implementation of a police crisis intervention team. South. Med. J. 2014, 107, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan-Saville, J.S.; Tan, L.; Gayed, A.; Barnes, C.; Madan, I.; Dobson, M.; Bryant, R.A.; Christensen, H.; Mykletun, A.; Harvey, S.B. Workplace mental health training for managers and its effect on sick leave in employees: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.B.; Joyce, S.; Tan, L.; Johnson, A.; Nguyen, H.; Modini, M.; Groth, M. Developing a Mentally Healthy Workplace: A Review of the Literature; National Mental Health Commission: Sydney, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzhugh, H.; Michaelides, G.; Daniels, K.; Connolly, S.; Nasamu, E. Mindfulness for performance and wellbeing in the police: Linking individual and organizational outcomes. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2024, 44, 566–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehl, K.S.; Elliot, D.L.; Goldberg, L.; Moe, E.L.; Perrier, E.; Smith, J. Economic benefit of the PHLAME wellness programme on firefighter injury. Occup. Med. 2013, 63, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lopes, S.; Lavelle, T.; Jones, K.O.; Chen, L.; Jindal, M.; Zinzow, H.; Shi, L. Economic evaluations of mindfulness-based interventions: A systematic review. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 2359–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrone, P.; Tehrani, N.; Tehrani, R.; Horsley, A.; Hesketh, I. Economic evaluation of a psychological surveillance and support programme in the UK police force. Int. J. Emerg. Serv. 2024, 13, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstede, G. Culture and organizations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 1980, 10, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijnen, B.F.M.; Lokkerbol, J.; Boot, C.; Havermans, B.M.; van der Beek, A.J.; Smit, F. Implementing interventions to reduce work-related stress among health-care workers: An investment appraisal from the employer’s perspective. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2020, 93, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, J.T.; Fortney, J.C.; Austen, M.A.; Pyne, J.M. Cost-effectiveness of telemedicine-based collaborative care for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noben, C.; Smit, F.; Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Ketelaar, S.; Gärtner, F.; Boon, B.; Sluiter, J.; Evers, S. Comparative cost-effectiveness of two interventions to promote work functioning by targeting mental health complaints among nurses: Pragmatic cluster randomised trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dongen, J.M.; van Berkel, J.; Boot, C.R.L.; Bosmans, J.E.; Proper, K.I.; Bongers, P.M.; van der Beek, A.J.; van Tulder, M.W.; van Wier, M.F. Long-term cost-effectiveness and return-on-investment of a mindfulness-based worksite intervention: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linos, E.; Ruffini, K.; Wilcoxen, S. Reducing burnout and resignations among frontline workers: A field experiment. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2022, 34, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, K.J.; Wanchek, T.N.; Lobo, J.M.; Keim-Malpass, J. Evaluating the costs of nurse burnout-attributed turnover: A Markov modeling approach. J. Patient Saf. 2022, 18, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layard, R.; Series, M.W. Measuring Wellbeing and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Using Subjective Wellbeing; Measuring Wellbeing: Series–Discussion Paper 1; Center for Economic Performance: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, M.V.; Sikorski, E.A.; Liberty, B.C. Exploring the cost-effectiveness of unit-based health promotion activities for nurses. Workplace Health Saf. 2013, 61, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, E.J.; Fragala, M.S.; Birse, C.E.; Hawrilenko, M.; Smolka, C.; Ambwani, G.; Brown, M.; Krystal, J.H.; Corlett, P.R.; Chekroud, A. Assessing the impact of a comprehensive mental health program on frontline health service workers. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, 2nd ed.; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, S.V. Interpreting Estimates of Treatment Effects. Pharm. Ther. 2008, 33, 700–711. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, E.Y.; Park, Y.; Li, X.; Segrè, A.V.; Han, B.; Eskin, E. ForestPMPlot: A Flexible Tool for Visualizing Heterogeneity Between Studies in Meta-analysis. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2016, 6, 1793–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, S.; Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000, 56, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gayed, A.; Milligan-Saville, J.S.; Nicholas, J.; Bryan, B.T.; LaMontagne, A.D.; Milner, A.; Madan, I.; Calvo, R.A.; Christensen, H.; Mykletun, A.; et al. Effectiveness of training workplace managers to understand and support the mental health needs of employees: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2018, 75, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Domain | Target | Search Terms |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Public safety personnel | Firefighters Police officers Law enforcement Dispatch Communication officers Paramedic Emergency medical technician Emergency medical service First responders Correctional officers Emergency room personnel Nurses Public Safety Personnel |

| Intervention | Resilience training programs | Prevention Resilience Coping (skills) Family coping Stress reduction Skill building Psychoeducation Mental health awareness (training) Stigma reduction |

| Comparison | Pre-post interventions | |

| Outcome | Return on investment | ROI Economic evaluation Cost–benefit |

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adult (≥18 years) public safety personnel and frontline healthcare professionals exposed to PPTEs | Studies involving individuals with clinically diagnosed mental disorders or positive screens on validated psychological instruments |

| Intervention | Mental health programs designed to proactively mitigate the impact of PPTEs | Studies addressing non-PPTE occupational stressors (e.g., work-related demands, organizational stress) |

| Outcome | ROI analysis, including pre-post intervention cost assessment | Studies without ROI analysis or cost–benefit evaluation |

| Language | English-language studies | |

| Publication Date | Published on or after 1 January 2015 |

| Study (Quality) | Sample Size | Population (Country) | Design | Program Description | Program Duration | Evaluation | Key Outcomes | Cost Saving Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| McCrone et al. (2024) [12] | 1000 | Police personnel (United Kingdom) | Decision analytic model, economic evaluation | Surveillance programtrauma therapy | Over a year | Pre-program, post-program | W/C assessed as an indicator of productivity, factoring in both absenteeism and presenteeism. Monetary measures: productivity gains translated into financial benefits. | The total screening cost was GBP 84,287 (USD 106,971), while the net gain in work productivity was GBP 241,672 (USD 306,713), resulting in a 187% ROI. |

| Wijnen et al., 2020 [15] | 303 | Healthcare workers (Netherlands) | RCT | Stress-Prevention at Work intervention for employees | 12 months | Pre-program, post-program at baseline, 6, and 12 months. | Productivity losses were measured using the Trimbos and iMTA Cost questionnaire in Psychiatry. | The program delivered significant cost savings for employers, with a modest investment of EUR 50 per employee yielding an average net monetary benefit of EUR 2981 per employee. |

| Painter et al., 2017 [16] | 265 | Veterans (United States) | Pragmatic randomized effectiveness | Telemedicine-based collaborative care model for PTSD | 12 months | Pre-program, post-program | Effectiveness measured QALYs derived from the Short Form Health Survey for Veterans and QWB scale. | The intervention cost USD 2029 per patient annually and did not lead to healthcare savings, resulting in an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of USD 185,565 per QALY (IQR: USD 57,675–USD 395,743). |

| Noben et al., 2014 [17] | 617 | Nurses (Netherlands) | RCT | Occupational physician condition, e-mental health condition | 6 months | Pre-program, post-program-6-month follow-up | Treatment response was defined as an improvement on the Nurses Work Functioning Questionnaire of at least 40% between baseline and follow-up. | At follow-up, WF improved by 20% in the control group, 24% in the occupational physician referral group, and 16% in the e-mental health referral group. The total average annualized costs per nurse were EUR 1752 for the control condition, EUR 1266 for the occupational physician condition, and EUR 1375 for the e-mental health condition. The occupational physician referral was the most cost effective, resulting in cost savings of EUR 5049 per treatment. In contrast, the e-mental health intervention had additional costs, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of EUR 4054. |

| Van Dongen et al., 2016 [18] | 257 | Research Institute for Physical Activity, Work and Health, (USA) | RCT | An eight-week mindfulness course that included mindfulness training, e-coaching, and supporting elements. | 8 weeks | Pre-program, post-program | Intervention costs, absenteeism, presenteeism, occupational health, healthcare utilization, workplace wellness activities, and work ability are measured. | ROI analysis was performed from the employer’s perspective using Net Benefits (NB), Benefit–Cost Ratio (BCR), and ROI metrics. To quantify precision, 95% bootstrapped CIs were estimated, using 5000 replications. |

| Linos et al., 2022 [19] | 536 | 911 Dispatchers (United States) | ITT analysis using (RCT) | A 6-week anonymous peer support intervention | 6 weeks | Pre-program, post-program | Burnout levels measured via CBI at three points: Baseline, immediately post-intervention and 4 months post-intervention. | Burnout reduction, improved retention, and decreased sick leave led to estimated cost savings of at least USD 400,000 for a mid-sized city. |

| Muir et al., 2022 [20] | 1000 | Registered nurses (United States)—hypothetical cohort | Cost–consequence analysis | Implementing a nurse burnout reduction program | 10 years | Comparison between 1: status quo 2: burnout reduction program | Burnout prevalence, turnover costs, inclusion/exclusion of burnout programs. | USD 11,592 per nurse per year in the burnout reduction program vs. USD 16,736 per nurse per year in the status quo. Overall savings: USD 5144 per nurse per year from reduced turnover costs. |

| Milligan-Saville et al., 2017 [7] | 128 | Fire And Rescue Service (Australia) | RCT | Mental health training program (“RESPECT”) for managers | 4 h | Pre-program, post-program-6 month follow-up | Work-related and standard sick leave rates were calculated. | The cost of work-related sickness absence was AUD 10,151.53 per manager less in the intervention group. This ROI is GBP 9.98 for every pound spent on manager mental health training. |

| Moran et al., 2020 [4] | 80 | Nursing staff (United States) | Economic evaluation using a Markov model | RISE program as a peer-support program, helps hospital staff cope with stressful events. | 1 year | Markov model to compare costs and benefits with and without the program | NMB, the budget impact was calculated based on the program’s cost, nurse turnover, and nurse time off. | The RISE program cost per nurse was USD 656.25. The mean NMB was USD 22,576.05. |

| Fitzhugh et al. (2024) [9] | 477 | Police officers and staff (UK) | RCT | Two mindfulness apps aimed at improving well-being: Mindfit-Cop and Headspace | 24 weeks, 10 weeks | Pre-program, post-program | (CERs) falling below Layard’s (2016) acceptability threshold of GBP 2500 per additional point [21]. | The (CER) was calculated based on improvements in life satisfaction and productivity (measured by absenteeism and performance changes). Both apps were determined to be cost effective, falling below Layard’s (2016) acceptability threshold [21]. |

| Palumbo et al., 2013 [22] | 80 | USA | Observational evaluation. | Wellness program implemented in a hospital | 6 months | Pre-program, post-program | Improved participation and staff satisfaction while potentially reducing absenteeism. | The program led to an estimated cost reduction of USD 11,409.17 in unscheduled absences. With a total intervention cost of USD 7662.50 for 80 employees, the ROI was calculated at USD 3746.67. |

| Kuehl et al., 2013 [10] | 1369 | Firefighters (USA) | Retrospective quasi-experimental study. | The PHLAME program, a peer-led workplace health promotion program | 12 sessions over the course of the program | Pre-program, post-program | WC claims and medical injury costs were reduced after implementation. | Fire departments participating in the PHLAME TEAM program demonstrated a positive ROI of 4.61–1.00, and the range of ROI is between 1.8 and 4.61. |

| Ward et al., 2023 [23] | 686 | USA frontline healthcare service workers | Retrospective cohort study | Digital mental health benefit | 6 months | Pre-program, post-program | Clinical improvement measures were PHQ-9 scale for depression and GAD-7 scale for anxiety; workplace measures were employee retention and SDS for functional impairment. | Participants reported 0.70 (95% CI, 0.26–1.14) fewer workdays per week impacted by mental health issues, corresponding to USD 3491 (95% CI, USD 1305 USD 5677) salary savings at approximately federal median wage (USD 50,000). |

| Roesner et al., 2024 [5] | 1000 | nursing staff—German | Economic evaluation using a Markov model | Peer support program aimed at reducing the psychosocial burden from the second victim phenomenon. | 1 year | Pre-program, post-program | Reduced sick days, turnover costs, and absenteeism. | Average cost saving of EUR 6672 per healthcare worker. Main reason for the reduction is the reduction in dropouts, whereas the costs of sick day leaves are only moderately affected. The expected annual budgetary impact is estimated to be approximately EUR 6.67 M in the hospital considered. |

| El-Mallakh et al., 2014 [6] | 1454 | Police officer—USA | Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) | (CIT) program | 9 years | Pre-program, post-program | Cost savings are due to reduced hospitalization and jail time. | Acost savings analysis of a CIT program in a medium-size southern city was performed. The annual costs of a CIT program were USD 2,430,128 and the annual savings were USD 3,455,025. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azadehyaei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Gottschalk, T.; Anderson, G.S. Economic Evaluation of Proactive PTSI Mitigation Programs for Public Safety Personnel and Frontline Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 809. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050809

Azadehyaei H, Zhang Y, Song Y, Gottschalk T, Anderson GS. Economic Evaluation of Proactive PTSI Mitigation Programs for Public Safety Personnel and Frontline Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):809. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050809

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzadehyaei, Hadiseh, Yue Zhang, Yan Song, Tania Gottschalk, and Gregory S. Anderson. 2025. "Economic Evaluation of Proactive PTSI Mitigation Programs for Public Safety Personnel and Frontline Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 809. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050809

APA StyleAzadehyaei, H., Zhang, Y., Song, Y., Gottschalk, T., & Anderson, G. S. (2025). Economic Evaluation of Proactive PTSI Mitigation Programs for Public Safety Personnel and Frontline Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 809. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050809