Social Eating Among Child and Adult Hospital Patients: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

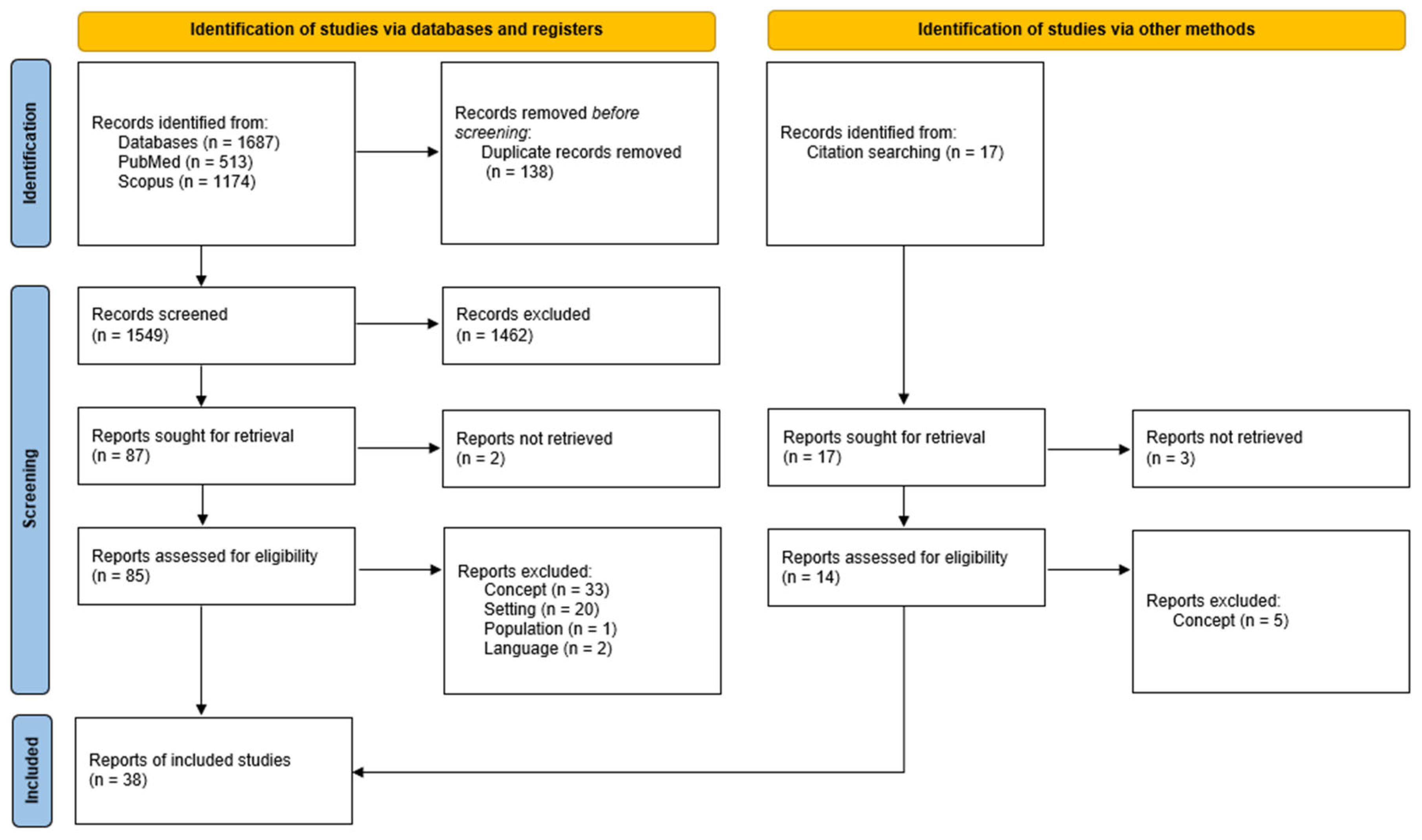

2. Materials and Methods

- What evidence exists regarding social eating in hospitals, more specifically in hospital wards?

- What factors are important to consider when exploring the implementation and potential impacts of social eating in a hospital context?

- What does the identified research tell us about how social eating in hospitals can be supported, especially in the context of children’s hospitalisation?

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Population

2.3. Context

2.4. Concept

2.5. Search Strategy

2.6. Article Selection

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics—Date, Location, and Setting

3.2. Study Characteristics—Study Design

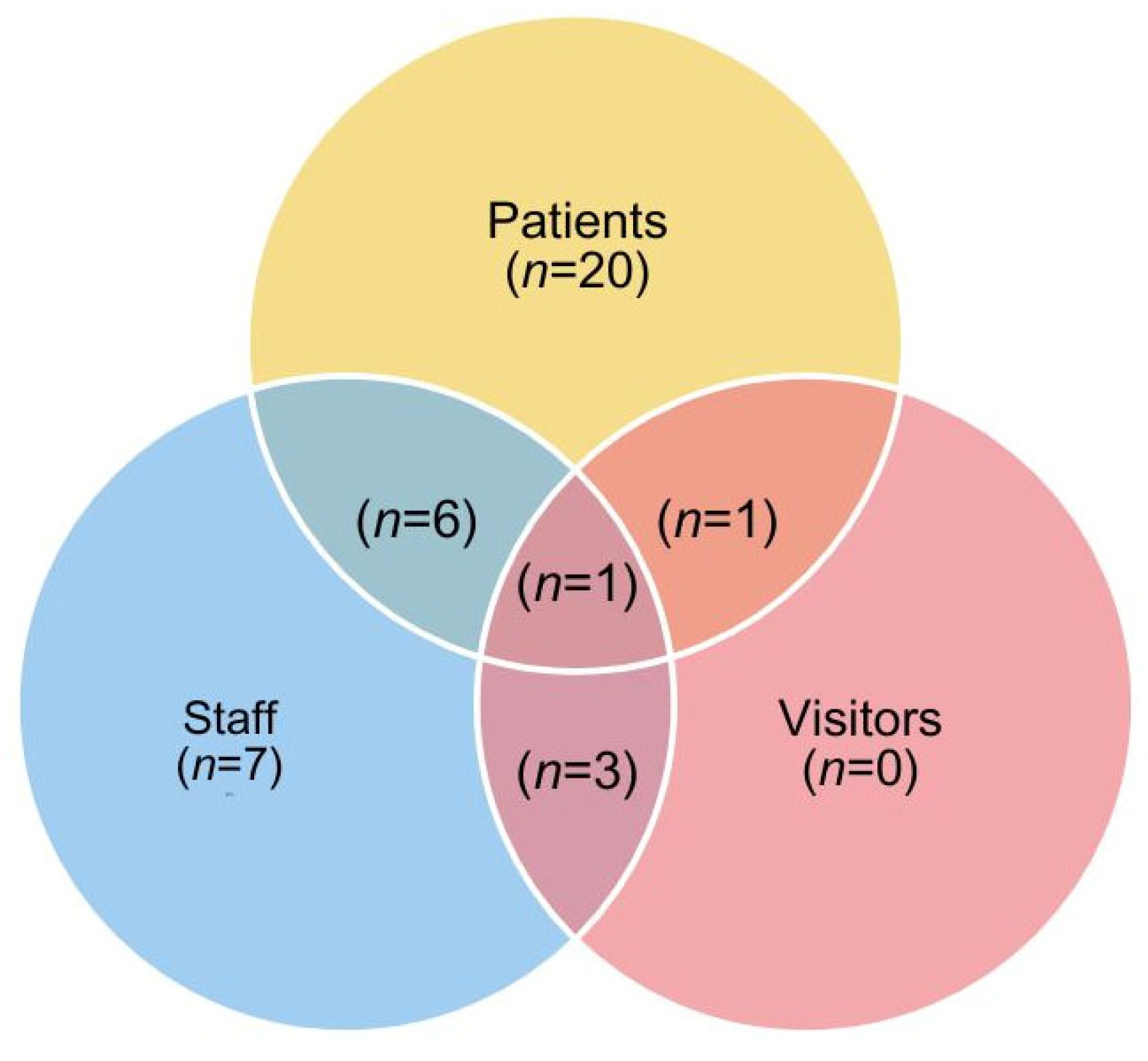

3.3. Study Characteristics—Participants

3.4. Study Characteristics—Findings

3.4.1. Measuring Sociality

3.4.2. Reported Impact of Aspects of Social Dining on Dietary Intake

3.4.3. Patient Preference for Dining Location

3.4.4. Influence of ‘Tablemates’

3.4.5. Staff and Visitor Involvement in Communal Dining

3.4.6. Eating Environment

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Reflections Related to Children’s Eating in Hospital

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| First Author, Date | Setting | Aim of Study | Study Design | Methodology | Patient Characteristics | Participants | Sample Size | Context | Key Findings Relating to the Research Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baptiste 2014 [28] | Ottawa, Canada. Geriatric rehabilitation center containing 60 beds. | To explore geriatric patients’ perceptions regarding eating at the bedside vs the common dining room. | Qualitative | Semi-structured individual interviews. | Aged 65 and over, eight patients, five women and three men. | Patients | 8 | Bedside eating or common dining room. | >Patients reported limited perceived control in choosing locations (staff). >Mood influenced location, e.g., feeling sad = not wanting to socialise. >Physical abilities, e.g., pain and fatigue, played a major role. >More time to eat in rooms and save personal time. >Loneliness and boredom were experienced when eating in rooms. >Mobility involved in moving to the dining room was seen as a benefit by patients. >The dining room environment was seen as pleasant, e.g., windows. >Possibility to socialise but also highlights tensions, e.g., if people do not talk. >½ said they preferred eating in the dining room, two had no preference, and two said they preferred eating in their rooms. |

| Beck 2017 [39] | Neurological care unit, Denmark | To investigate how health professionals experience participating in a mealtime intervention inspired by the concept of Protected Mealtimes (P.M) and intended to change mealtime practices. | Qualitative | Three focus groups with five participants in each. Semi-structured based on the mixed ‘funnel’ model. | Patients with varying neurological conditions | 15 health professionals working in a neurological ward, with mixed levels of exposure to the ‘Quiet please’ intervention. Mixture of roles, e.g., social worker, secretary, speech therapist. | 15 | ‘Quiet please’, goal = to change mealtime practices by creating an environment inspired by protected mealtimes. Based on PM but modified for the Danish neurological care context. Reduced noise and goal of calmness across the ward. | >Created a sense of togetherness across patients because they had something they could share. >Changes to the environment—e.g., folded napkin, flowers on tables, etc.—meant patients behaved differently, e.g., made their beds. |

| Beck 2017 [38] | Danish neurological unit | To explore the experiences of patients who were admitted to the neurological ward during an intervention, inspired by Protected Mealtime, that changed the traditional mealtime practice | Qualitative | 13 semi-structured interviews were conducted with patients. | Aged 30–83 with neurological conditions | Patients | - | ‘Quiet Please’ intervention | According to the patients, being considered as people made them experience the meal as a meal shared with other people and not as an institutional obligation. The aesthetic elements provided the patients with conversation topics that were unrelated to their diagnoses and symptoms. This was essential, according to the patients, because ‘small talk’ during the meal led to relationships with other patients, which potentially helped them eat a little more. Also, there were negative reactions to it, e.g., ‘Quiet Please pisses me off. It is nice to sit and talk or chat like we do at home when we sit and eat’. During the interviews, the aesthetic elements that were provided in the intervention, e.g., flowers on the tables, were shown to be meaningful to the patients because they conveyed a sense of care for the mealtime setting. The patients explained that their conversations with each other during mealtimes were important to develop a feeling of being at home while hospitalized, and mealtimes then became a common topic of conversation. |

| Beck 2018 [48] | Denmark. Neurological unit with three small wards | To study what patients who are afflicted with a neurological disease experience and assign meaning when participating in mealtimes during hospitalisation. | Qualitative | 10 semi-structured interviews. | 10 participants aged between 27 and 78 years with neurological diagnoses. | Patients | 10 | Mealtimes were eaten either at tables in the hallway, in bed, or at shared tables next to the bed. | >Many chose to eat in their beds to maintain privacy; the hallway setting was stressful, and it was not possible for patients to eat with visitors due to the hectic and busy hallway dining area. >Equally missed social interaction. >Socialisation was sometimes made tricky by the varied conditions patients had; the bed was a safe place. >Conditions and treatment sometimes made eating unappetizing. |

| Beck 2019 [57] | Danish neurological unit | To examine the meaningfulness of the phenomenon of hospital meals for hospitalized patients with a neurological disease. | Qualitative | 23 interviews. | Patients with varying neurological conditions | 23 participants with different neurological diseases/diagnoses. Aged 27–83. | 23 | Mealtimes on a neurological disease unit | >Patients explained that they often felt lonely during mealtimes. >Found a community with fellow patients through identifying each other’s loneliness during mealtime situations, which helped facilitate a sense of normality. >Eating in bed is associated with calmness and comfort. >Patients described how just sitting together and eating (even without long conversations) could be a peaceful activity, a positive association with the possibility of small talk that avoided serious thoughts about their current condition. Though staff did not eat with patients, it offered opportunities to become acquainted with them. |

| Bryon 2008 [50] | Geriatric–psychiatric ward in a Belgian Academic Hospital. Long-term treatment ward for older people | To obtain insight into the care process surrounding mealtimes within a geriatric–psychiatric ward from the perspective of the caregivers | Qualitative | Participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and focus groups. | Patients had long-existing psychiatric (schizophrenia, personality disorder, etc.) and/or physical problems (diabetes, Parkinson’s disease) | Head nurse, five nurses, three nursing aides, a worker, the psychologist, the occupational therapist, and the nurse manager. | 13 | Meals were served in two common dining rooms: one for residents who eat normal food and one for residents on a special diet. Those needing eating assistance shared a table. A total of 34 residents were spread over two dining rooms, eating with three to four persons at a table. The dining rooms were small, which led to problems with wheelchairs. In a rather limited space, a large number of residents were present, which resulted in a lot of commotion. | Caregivers experience that with their help, the mealtime can become a moment of (a) social interaction, (b) attention to self-care, and (c) enjoyment. By eating in the common dining room, residents are taken out of their isolation. Moreover, residents stimulate and supervise each other to leave their rooms. During the meals, social skills can be practiced and stimulated. Eating together makes the mealtime more enjoyable and promotes appetite. Patients also laid the table and put their plates away, giving them agency. Agreements were made with patients about eating etiquette in the dining room; if not followed, then they would eat in their rooms. Individualizing the meal in accordance with the different needs and wills of patients is difficult when using this form of mealtime care. Patients who lived in a closed ward would eat together even when at times, some would probably want to eat alone. However, allowing some patients to eat alone or letting them choose dining location makes it harder for staff to manage. Made the dining room look nice, e.g., using decorations and special menus, etc., during holidays. Those with special diets ate in a separate dining room, as otherwise, patients traded their meals and took things from the plates of others; it was not easy to work in this kind of dining room. |

| Davies 1980 [34] | Liverpool, UK The dayrooms of two wards in a continuing-care geriatric hospital. | To provide greater opportunities for social interaction and for choice over the way the meal is served. | Quantitative | Participant observations and any social interactions were recorded. | Patients were of similar medical status, all had multiple handicaps, and nearly all were confined to wheelchairs. | 27 patients (7 men) in Ward A and 25 women in Ward B | 27 | In Ward A, most patients sat with their backs to the walls, and one row of wheelchairs was lined across the centre of the room. Ward B had a smaller dayroom. Three groups of patients sat at round tables, the others in rather cramped conditions around the walls. The trolleys had to be kept in the corridor. Intervention for making Ward A more social changed the seating such that there were two tables, each seating six, and introduced decorations, such as a set of cloths, water jugs, etc. Trolleys were moved to the corridor to reduce noise. | Ward B had more interactions and more varied interactions at the beginning of the study. After the intervention, there was an increase in social interactions in Ward B. Three factors deserve consideration: the ‘social distance’ between staff and residents, the physical environment, and the role of the ward’s sister. When placed at tables, talk was facilitated, and helpful behaviour became possible. |

| Dickinson 2005 [44] | 26 bed units in the UK. | To implement patient-focused mealtime practice for older patients within a hospital unit and promote healthy ageing by improving mealtime care by working towards a patient-focused and enabling culture. | Qualitative | Focus groups, interviews, and observations of six mealtimes. | Older patients with complex discharge needs | 19 staff took part in focus groups, interviews with six patients, and observations of ward mealtimes. | 25 | The physical environment was poor, with plastic garden tables used in the dining room as tables. | >Social aspects considered poor by staff and patients affected by the environment, but also from a lack of facilitation by staff. >Occurred only by chance. >All patients interviewed said they would like the opportunity to share their meals with staff from the unit; one patient had performed this before and said it was beneficial. |

| Edwards 2004 [31] | Women’s Health Unit in a National Health Service (NHS) hospital. | To ascertain how food intake might be affected by allowing hospital patients to eat in the company of others | Quantitative | Plates were weighed after patients had eaten, and nutritional analysis was carried out. | Patients were hospitalised for a variety of surgical procedures in the age range of 36–89. | Patients at table (4) aged 36–62 years, with a mean age of 49. Patients by the bed (5) aged 60–86 years, with a mean age of 75. Patients in bed (4) aged 49–89 years, with a mean age of 63. This was only a small cohort. | 4 | Group 1. Around a table Group 2. Sitting by their bed Group 3. Sitting in bed | >Significant increase (p < 0.05) in mean daily energy intake for the group sitting around the table (Group 1) over the other two groups. >When individual meals are compared, there were no significant differences in the groups for the evening meal; at the midday meal, Group 1 was significantly different from both Groups 2 and 3; and at breakfast, the only significant difference was between Groups 1 and 2 |

| Furness. 2023 [53] | All sites of Austin Health, a teaching hospital in Australia. Including a large tertiary acute hospital (Austin Hospital, AH), a subacute, aged-care and rehabilitation setting (Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital), and a dedicated rehabilitation setting (Royal Talbot Rehabilitation Centre) | To describe the mealtime experience using the qualitative components of the Austin Health Patient Mealtime Experience Tool (AHPMET) to complement the quantitative findings of this tool. | Mixed methods | Questionnaire with opportunities for participants to provide qualitative feedback. | Adult inpatients. The median age was 77 (range 19–101) years, and the median length of stay was 19 (range 1–270) days. | 149 inpatients who had received meals for at least one full day. | 149 | The majority (75%) of participants consumed their meals in an individual or shared room, while the remainder (25%) consumed their meals in a shared dining room | >Environment theme identified factors that inhibit mealtime intake and are a deterrent to the mealtime environment, including sensory aspects of the environment, other patients, accessibility and functionality of the mealtime setup and dining area, and clinical impact symptoms. ‘The structure of the room makes it really noisy and loud—the high ceilings and big openness echoes noises—loud chattering and loud banging and crashing of the dishes in the kitchen and plates being cleared—makes it hard to hear, not peaceful’ (male, 40 years, LOS 165 days). >Facilitators to mealtime/nutritional/food intake and a pleasant MTE were also identified, such as socialisation during meals and a mealtime environment that facilitates such interaction. Additionally, the available furniture used during mealtimes affected intake and/or comfort. ‘Was able to choose who I got to eat with and talk which was good’ (male, 77 years, LOS 13 days). >Atmosphere theme had 9 positive comments and 22 negative ones (perceived negatively) >Features of the physical environment, including noise, visitors and other patients, room surroundings and ambience, interruptions by hospital staff, and smells or odours were not commonly reported to affect food intake in the study. |

| Gardner 2022 [41] | Cotswold House ED unit in Oxford, UK | To understand the system of our dining room, including the environment, purpose, processes, and how people interact with these and each other | Mixed methods | Observations in the dining room and recording the number of eating disorders, and qualitative feedback gathered from patients and staff about the intervention. | The average age of patients admitted is 28.9 (17.1–60), 97% identify as female. | Patients and staff | - | Three changes were introduced, including (1) a host role in the dining room, (2) a guide to the dining room for new staff along with competencies, and (3) a dining goals group. Staff normally eat with patients in the dining room; however, because of infection control changes through the pandemic, staff have been unable to eat with patients, which has led to the loss of role modelling of normal eating in the dining room. | The dining room has been reported by patients and staff as a very stressful environment. For patients, this can manifest itself in increased eating disorder behaviours such as eating very small mouthfuls, hiding food, smearing food, or eating foods in a certain order, which leads to maintaining the eating disorder. Results to date show a 33.44% reduction in observed ED behaviours between baseline and the post-test period. |

| Gardner 2021 [40] | Cotswold House ED unit in Oxford, UK | To decrease the number of ED behaviours at mealtimes in the dining room through the implementation of initiatives identified through diagnostic work. | Mixed methods | A survey was conducted to assess mealtime protocols across 22 eating disorder units, and semi-structured interviews were conducted with staff at three units. | On average, six patients were in the dining room at mealtimes. All patients admitted in 2019 were women and ranged from 19 years to 68 years old (the mean age is 33 years). The average length of stay across 2019 was 73 days. Most had anorexia nervosa. | Patients and staff | - | Mealtimes occurred six times a day in the ED wards. An introduction to the host’s role was performed. During the pandemic, staff stopped eating with patients. Two dining rooms were in the unit; the main dining room was a small room with four tables and was for those in recovery, while the upstairs dining room was for those meeting criteria. | Reduction in the number of ED behaviours observed could be that the dining room feels less chaotic and more predictable as a result of the host role, which has addressed ED behaviours triggered by anxiety and distress from environmental disturbances. The most frequently observed behaviours were unusual eating behaviours during mealtimes, for example, tearing up food, being detached at mealtimes/not talking or making conversation, and becoming anxious about unexpected changes to meal service. Patient feedback themed around feeling more supported by staff and the dining room feeling more organised. Both staff and patients acknowledge that mealtimes in the dining room are still a difficult experience, but much can be achieved. |

| Hartwell 2013 [35] | UK, two orthopaedic wards in an acute care hospital | To evaluate the attitudes of staff towards implementing a dining room eating experience in a hospital ward by considering not only physical constructs but also the social domain and operational practice of staff providing the hospitality. | Qualitative | Interviews with hospital staff. | Patients were undergoing elective surgery for hip/knee replacements and had a length of stay of approximately 10 days. 12 males, 6 females. | Staff involved in group dining were interviewed. | 18 | Enhanced dining environment facilitating the creation of communitesque experiences. The tables were covered with a tablecloth and laid with cutlery, crockery, glasses, jugs of water, and condiments. This environment was well lit and provided a quieter atmosphere than normally found in wards. | Easier to serve food, e.g., courses, food stayed hot. Reduced the amount of legwork needed by staff with everything in one place. Provision of a more ‘dignified’ and ‘civilised’ environment in which patients could eat. Providing a group dining experience encouraged patients to become mobile and increase their motivation. Patients enjoyed the social experience of the meal. More hygienic- away from the clutter of beds. Gave a sense of ‘normality’, recreating mealtimes that they may have at home while providing an environment that is familiar. Support/clinical staff observed that patients at the very early stages of recovery were likely to be in too much pain to want to socialise. Some patients may still require catheters and drips, and in those circumstances, feel that to be wheeled into a dining area is too undignified, inappropriate, and uncomfortable. |

| Hartwell 2016 [64] | Acute Care Hospital with 26 wards including medical, elective surgery, maternity, and intensive care (UK/NHS) | To identify and examine all perceived aspects of the meal experience from the patient’s viewpoint and to quantify the impact of each one | Quantitative | Questionnaire with scalable answers drawn up from qualitative interviews. | The mean age was 69.1, with the minimum being 25 and the maximum being 94 years old. Orthopedic ward patients. | 296 responses, 120 males, 176 females, with 2 individuals saying they had never eaten hospital food before | 296 | Eating at the bedside | >On social, staff, and ward, the more experienced respondents tended to be more positive, although differences here were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). >Demonstrated from first principles that food quality, followed by service quality, were the most important predictors of customer satisfaction, thereby confirming findings of some previous authors. After this, the social environment, the personal characteristics of the patient, and the immediate eating environment were the most important factors. |

| Holst 2017 [36] | Three departments in Aalborg University Hospital, Denmark, with around 26 beds. | To improve energy and protein intake by improving the aesthetics of the surrounding environment and providing individualized meal services. | Mixed methods | Observational study, 24-h food intake registrations for 3 d consecutively, a questionnaire, and a semistructured patient interview. | Patients from three departments: (medical infectious diseases, haematology, and heart–lung surgery) | 30 patients with a mean age of 62.9. Mean LOS-6 days before intervention. A total of 37 patients with a mean age of 67.2 after intervention | 30 | Changes to the environment—table cloths and small vases—were purchased. Coloured tray mats and napkins were introduced for all main meals. Lastly, soothing background music was played during lunch and dinner. Also, nutritional information was given to patients. | >Patients found the environment very welcoming and inviting, allowing patients to socialize more with each other during meals. One patient made the following comment: “The atmosphere is company increases appetite, eating more with others”. >Overall group showed significant improvements in energy intake |

| Jong 2021 [55] | Australia Subacute care wards 1x rehabilitation ward and 1x geriatric evaluation and management ward | To understand and explore staff’s perspectives and experiences of communal dining in subacute care, and the impacts on staff mealtime practice | Qualitative | Participant observation and ethnographic/semi-structured interviews. | Older patients from a geriatric and rehabilitation ward. | Staff involved in nutrition care or present on the ward at mealtimes. Broad range of professionals included. | - | >The rehabilitation ward had a small dining room at the rear. >The geriatric ward had a large, central dining room. | >Three themes identified: (i) benefits to patients, (ii) logistical and practical challenges, (iii) supportive cultural factors. >Change of scenery, home-like environment, more comfortable and easier transition. >Staff played a role in higher levels of socialisation. >Positive relationship with intake and mobilisation. >Transportation and time pressures are difficult; the location of the dining room relates to levels of supervision. >Dining room design impacts convenience, e.g., toilet locations and table designs not being wheelchair friendly can impede socialisation. >Cognition impacts the desire to use the dining room. >Staff encouragement and normalisation of the dining room have an impact on use. |

| Jonsson 2021 [59] | Sweden, four wards within two Swedish public hospitals that care for adult medical, orthopaedic, and geriatric patients | To explore how hospitality was performed by nursing staff and meal hosts in the dining room environments at four hospital wards, and to explore the specific role of the room and its artefacts in facilitating or hindering acts of hospitality | Qualitative | Ethnographic study, non-participant observations with interactions initiated by staff or relatives (researcher not involved in provisioning). | - | Nursing staff, staff involved in preparing food, and relatives of patients. The patients who were present in the dining room environments were indirectly observed. However, the focus was not on what the patients did or said but on how the staff acted towards the patients. | - | Both wards A and B had different dining room settings. A—Dayrooms with two tables and six assigned seats, used for dining and other activities. B—Five or six tables with six chairs at each table, chairs have wheels, and meal boxes on display in fridges. | The ability to perform hospitality during mealtimes differed between the wards and could be hindered as well as facilitated by the location of the dining room environment and the materiality within. Hospital A, silence in the room was emphasised by the noise of hospital machinery. In hospital B, the function of a meal host was observed to promote a sense of commensality for the patients during mealtimes. The patients were not alone, even if they dined alone at their tables. During one observation at hospital A, the dining room was reorganized to enable nine patients to sit together and eat their lunch. The tables were brought together, creating one long table. This arrangement seemed to facilitate and promote a positive atmosphere for the patients during the meal, as well as ensuring that several nursing staff attended the meal service. However, rearranging the tables also created a crowded feeling in the room. |

| Justesen 2014 [56] | The gynaecology and cardiology wards of a Danish Public Hospital in the eastern part of Denmark | To introduce and explore whether the application of the participant-driven photo-elicitation (PDPE) research method in a hospital meal context can contribute to a richer insight and understanding of the experiences and perceptions of hospital meals. It aims to expand the conceptualisation of hospital meals by providing access to a multi-sensory response to meal experiences. | Qualitative | Photo elicitation and follow-up interviews. | Patients from the gynaecology ward and the cardiology ward | Eight patient participants, aged 19–81. Four males, four females | 8 | Buffet trolley system onwards | >Patients ate alone. However, opportunities for social activity took place around the buffet trolley. Patients could relate to each other and created a patient community. >Some patients avoid social interactions while eating to maintain sense of identity. |

| Justesen 2016 [65] | The gynecology and cardiology wards of a Danish Public Hospital in the eastern part of Denmark | To explore how hospitality can be co-created in a hospital food environment and how it emerges from socio-material interactions | Qualitative | Ethnographic, structured, and unstructured observations carried out over 6 months. Interviews based on photo elicitation. | Patients at the gynecology ward were mainly cancer patients or patients hospitalized for surgery. | - | - | Dinner served from a buffet trolley at lunch onwards. | >Patients themselves also took the initiative to transform the hospital room into a hospitality space, e.g., pushing chairs against a dinner table and calling it a ‘cafe’, also others commented on how the physical space made a difference—e.g., eating in a chair more. |

| Larsen 2021 [54] | Denmark. North Denmark regional hospital, and Aalborg University Hospital | To identify the experiences of patients about eating situations, wishes, and needs in connection with meals during their stay in the hospital. | Qualitative | 20 semi-structured interviews that lasted between 7 and 54 min | - | Aged 51–92. Twenty participants chosen based on sex, age, and surgical and medical departments to capture the nuances of the patient experience. | 20 | At both hospitals, patients could eat food in the living room or in their wards. At Aalborg, Healthcare Professionals (HCPs) presented patients with a menu and served the requested food. At North Denmark Hospital, patients who were able to walk around could choose food from the buffet. | >The hospital setting affects the eating experience, does not create a meal break, and is reminiscent of illness. >Eating around others might serve as a motivation to eat more. >Eating together can provide an opportunity for company and conversation. >Physical discomforts influence how they experienced the meal, e.g., vomiting/spilling food. >Own weaknesses or disabilities affected their desire to eat in front of others, as well as their dignity. >Social interaction depends on who they are eating with. |

| Long 2012 [52] | UK, three NHS and one independent eating disorder service, all four sites included inpatient care and meals as part of that treatment. | To investigate inpatient perceptions of mealtimes on eating disorder units. | Qualitative | Individual semi-structured interviews with participants. | Patients from one independent unit and three NHS units. | 12 patients, 5 from an independent unit and 7 from the three NHS units. All were females, with a mean age of 22 years. | 12 | Group meals in the dining room for a period of over two weeks | >Dining room organisation/layout is important. For example, table shapes, sizes, and distances from one another create different dining experiences. >Distractions. For example, staff talking and the radio on can be both helpful and a hindrance. >Emotional experiences. For example, being new to the ward, feelings of anxiety, embarrassment, and panic. >Behaviours learnt from other patients and ‘feeling sucked into the way people are eating’, comparisons made with other patients. >Rivalry between patients. For example, who took the longest time to finish the meal, feelings of being watched and judged. >Loss of identity through lack of individualisation. |

| Long 2012 [58] | UK, 22 eating disorder units, children, adolescents, as well as adults. In total, 14 (63.6%) were NHS services and 7 (31.8%) were independent units (one unit did not provide this information). Five (22.7%) units provided care for those under 18 years old, 10 (45.5%) for over 18, and 7 (31.8%) for all ages. | To increase our understanding of the way in which mealtimes are currently conducted within specialist eating disorder units, and second, to qualitatively explore staff perspectives of mealtimes. | Mixed methods | Survey questionnaire and follow-up interviews with staff from selected units. | The units catered for a range of ages, from under 18 (beginning at 11 years old) through to adult units | Individual interviews were conducted with 16 staff members (2 males and 14 females) who had varying lengths of experience in providing inpatient care | 16 | The three ED units they used for interviews all had dining rooms. | Thirteen units (59%) reported that ward staff would at least sometimes sit with patients without themselves eating a meal. Reasons for this included unit policy not to eat with patients and personal choice (such as having plans to eat following their shift). The majority of units (90.9%) reported at least sometimes having non-nursing members of staff eating with patients. Creating a calm dining environment was important in reducing mealtime stress. Staff found meals daunting and emphasised how they felt watched while eating, as if they were punishing people. Staff opinions were split as to whether they should be expected to eat alongside patients or not. Many staff believed this to be an important factor for patients, as it provided role models and normality for the situation. Others saw having to eat alongside patients as distracting from the care they provided. Some staff felt they should eat with patients, but chose not to, because they did not feel comfortable. |

| Markovski 2017 [29] | Australia, subacute setting across two Western Health Care services | To investigate the effect of the ‘Dining with Friends’ programme on energy and protein intake in hospitalised elderly patients, identify whether patient groups at risk of malnutrition could benefit from a communal dining environment, and identify patients’ preferred environment for meal consumption. | Quantitative | Data collected regarding food intake and patient satisfaction on 54 separate midday meals. Used a malnutrition screening tool (MST) | Majority in rehabilitation for 1–2 weeks and had a cognitive impairment. The mean age was 79 years., 73% were female, 45% were screened as being at risk of malnutrition, and 24% reported a poor appetite. | 34 patients. Excluded patients who needed feeding assistance or where it was not deemed socially appropriate for them to participate | 34 | Comparison between dining room and bedside meal experience. Two midday meals observed, one in the bedroom and one in the dining room. | >Intake of protein and energy increased by 20% when the meal was consumed in the dining room. >Majority of patients identified the dining room as their preferred eating site, 68%. >All groups identified at risk of malnutrition consumed more energy and protein in the dining room. The intake of energy and protein increased by 30% when patients who were underweight (BMI < 22) ate in the dining room. The intake of energy and protein increased by 30% when patients identified with significant cognitive impairment ate in the dining room. |

| Mårtensson 2021 | Paediatric care facility in Sweden | To investigate whether the Five Aspect Meal Model could be appropriate for children with a gastrostomy tube in caring science and paediatric care. | Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews | Children being treated for cancer, using gastrostomy tubes | Patients and their families/parents, three children and four parents included. | 7 | Mealtimes for children with gastrostomy tubes in hospital and at home. Families of children. | >Flexibility needed as mealtimes occurred in different areas/rooms, e.g., dining table, bed, and couch. >Kitchen environment experienced as warm, personal, and relaxed, and described as an optimal place for mealtimes. >Issues eating orally meant patients did not always want to eat at the table. >Room environment had an impact on the desire to eat/appetite. >Most mealtimes spent in bed, even when the family was eating at the table. >Educational meals seen as more social and enjoyable by parents. >Parent loneliness during mealtimes. |

| Mathiesen 2021 | Denmark. Specialized acquired-brain injury unit. | To identify and resolve issues in the existing acoustic environment of a common dining area of a hospital ward. Explore how improvements to the acoustic eating environment, including music playback, affect patients’ mealtime experience, behaviour, and food intake. Examine various musical genres and their appropriateness for eating situations in hospital settings. | Mixed methods | Plates were weighed after patients finished each meal throughout each phase. Participant observation, social interactions, and comments about the intervention were captured (1 = no interaction, 5 = lots of interaction). Semi-structured face-to-face interviews were carried out with patients. | 17 patients with an acquired brain injury: 11 males, 6 females. The mean age was 64.5 years. | Patients | 17 | Common dining room for patients. Soundproofing materials were installed in Phase 2 In Phase 3, music was introduced to the common dining area. | The amount of social interaction decreased from the Baseline (Mean Rank = 99.79) to Phase 2 (Mean Rank = 81.85) and subsequently increased in Phase 3 (Mean Rank = 83.62), H2 = 8.745, p = 0.013. All patient interactions were, however, reported as being positive in the observation form, and no observations of agitated behaviour were made at any point throughout the study. The concept of commensality saturated the interviews and was articulated as a significant and indispensable part of the participants’ daily lives (inside and outside the hospital). Prior to the acoustic intervention, hospital noises were perceived as getting in the way of being able to talk to one another; intervention meant they were able to talk to one another with more ease. Cosiness helped interpersonal relationships. The content of conversations shifted away from serious topics and created commonalities between people. Increased enjoyment from food. Average fluid intake increased. |

| Melin 1981 [33] | Sweden. Ulleraker hospital. | To evaluate the effects of changes in furniture arrangements and mealtime routines on two types of behaviour- communication and appropriate eating | Quantitative | Observations of communication occurring at mealtimes between patients and between patients and staff | Psychogeriatric patients. | 21 patients, 15 diagnosed with senile dementia, 2 suffering from cerebral atherosclerosis, 2 with presenile dementia, and 2 with chronic schizophrenia. The mean age was around 81 years. | 21 | Ward contained four-bed rooms, two-bed rooms, and single-bed rooms, as well as a lounge, a dining area, and an occupational therapy room. One experimental group and one control group. Changes in the physical environment were introduced in the second week, and changes to mealtime routines were introduced in the third week for the experimental group. Ward was sparsely decorated, and furniture was placed along the walls. Patients in the experimental group were placed around small tables and, instead of trays, were given saucers, cups, etc. Patients were able to serve themselves, with staff not present, during coffee time. At mealtimes, patients grouped around small tables with serving dishes, salt, pepper, napkins, soft drinks, beer, etc. | >Significant increase in communication in the experimental group. >Inactivity might have been influenced by the social setting. >The changed meal situation meant that patients had to communicate to acquire what they wanted from the table. |

| Neo 2021 [62] | One of the largest tertiary hospitals in Singapore. Eight medical and four geriatric wards. | To explore enrolled nurses’ perceptions of providing nutritional care to hospitalised older people in Singapore’s acute care setting. | Qualitative | Descriptive study. Individual face-to-face semi-structured interviews. | Older patients who required more assistance in nutritional care | 15 enrolled nurses aged between 26 and 49 | 15 | Patients eating in bed/at the bedside | Participants felt that families’ involvement was critical in providing nutritional care to hospitalised older people; they recommended that families actively participate in hospital mealtimes to improve their nutritional intake. For example, families bringing food and eating together recreate a home environment and encourage patients to eat. |

| Ottrey 2018 [61] | One subacute ward from each of two locations within a large metropolitan healthcare network in Australia | To explore multiple perspectives and experiences of volunteer and visitor involvement and interactions at hospital mealtimes. In addition, to understand how the volunteer and visitor role at mealtimes is perceived within the hospital system. | Qualitative | 75 ethnographic and semi-structured interviews and participant observation | Patients were typically admitted to these wards for geriatric care or rehabilitation, for example, after a stroke or fracture. | 45 staff (including six leaders), five volunteers, and 11 visitors. | 61 | Meals eaten in bed with the option of dining room | Visitors were observed to facilitate shared dining experiences, often eating their food while sitting with the patient at mealtimes, enriching their experience of being in the hospital, and bringing in food. Nurses described how volunteers assisted at mealtimes by helping patients if needed and supervising those eating their meals in the dining room. Visitors and volunteers were seen as helping with well-being and providing interaction at mealtimes, although not all ate with the patient. |

| Paquet 2008 [43] | Rehabilitation unit of a university geriatric facility in Eastern Canada | Part of a broader investigation whose aim was to study the psychological and organizational determinants of food intake in institutionalized elderly patients. To build upon the interpersonal circumplex model of human interactions to evaluate how specific elements of the meal social environment contribute to the social facilitation of elderly patients’ intake. | Quantitative | Mealtime interactions observed and assessed for meal intake based on the proportion left on the plate. | Patients with a 4-week average length of stay. Over 65 years old. | 32 patients | 32 | Common dining room with a capacity of 24 patients | >The total number of interactions observed for participants and their interaction partners was positively related to energy intake. >Food intake by participants was associated with their communal behaviors, but not with their agentic behaviors. >Interaction per se may not be enough to explain the impact of the social environment on intake, and the specific nature of these individual behaviors and their complementarity may play an important role in the effect. The communal behaviors expressed by these patients had a positive impact on the amount of energy consumed by participants for that meal. |

| Rosbergen 2019 [32] | Regional hospital, Australian 16-bed acute stroke unit. | To explore the effect of environmental enrichment within an acute stroke unit on how and when patients undertake activities, and the amount of staff assistance provided, compared with a control environment (no enrichment) | Quantitative | Measuring the proportion of time doing physical, cognitive, and social activities | Stroke severity ranging from mild to severe among older adults. | A total of 30 participants in the control group and 30 in the enriched group. Mean age of control group = 76.0 and mean age of enriched group = 76.7. Control group: 56.7% male and 43.3% female. Enriched group: 73.3% male and 26.7% female. | 60 | The control group received standard therapy and nursing care that was provided mainly at the participants’ bedside. Embedding environmental enrichment included the transformation of public spaces in the acute stroke unit to communal seating areas for patients and families. Stimulating equipment (such as iPads loaded with therapy apps, music, books, newspapers, art, games, puzzles, and magazines) was distributed throughout communal areas and at the patient’s bedside, accessible 24 h a day, with communal breakfast and lunch also included. | >Environmental enrichment increased physical and cognitive activity and reduced time spent in bed on weekends. >Scheduled communal activity and provision of stimulating resources within a clinical environmental enrichment significantly contributed to increased activity levels in stroke survivors. |

| Sidenvall 1996 [51] | Rehabilitation and long-term care clinic with four wards, Sweden | To investigate cultural values and ideas concerning table manners and food habits expressed by patients in geriatric care. Studying the elderly’s perceptions of food habits in contrast to food served in the common dining room. | Qualitative | Informal ethnographic interviews comparing habits at home to those in the dining room | Stroke, fracture, rheumatoid arthritis, Parkinson’s disease, and peripheral circulation insufficiency were represented, even though the patients had several other diagnoses. | 23 females, 19 males. Born and raised in Sweden. Geriatric, with a mean age of 81 | 42 | The patients had their meals in a common dining room. | Patients with the retained ability to eat reported discomfort and loss of appetite due to the inability of others to remain clean. Such situations occurred when table-mates were unable to separate their own things from collective bowls, used their own spoon in the jam pot, or dug for cubes in the sugar basin with their fingers. ‘Troublesome atmosphere caused by eating problems that arose from conditions or treatment’. Difficulties in socialising when in pain or discomfort and wanting to focus on the food. Patients without handicaps seeking social contact found it difficult to initiate a conversation with handicapped table-mates or with those who had impaired hearing, bad sight, or were confused. Also expressed negative emotions, e.g., ‘sorrow’ when seeing that fellow patients were declining; their appetites becoming worse. On the other hand, healthy patients also expressed satisfaction with their table-mates and found the meal situation to be a moment of fellowship. |

| Sidenvall 1994 [42] | Two rehabilitation and long-term care Wards in Sweden | To investigate individual patients’ meals in geriatric care with respect to both the intentions of the nursing staff and assessments of patients, as well as to those patients’ experiences and the extent to which they expected to be able to influence the meal situation regarding behaviour and table manners, eating competence, and diet. | Qualitative | Ethnographic interviews, observations, and recorded data. | Dependent patients = 3 and independent patients = 15. Diagnoses varied from stroke to Parkinson’s to hip fracture. | 18 patients, 13 females and 5 males, with a mean age of 81. They were mixed with patients who were not allocated to the study in the dining room. 21 enrolled nurses, all female and with a mean age of 41, also took part. | 39 | Common dining room, patients divided in the room between those with dependent and independent abilities to eat. Patients also divided into two groups depending on eating ability, need for assistance, and conduct in the dining area. | Both patients and nursing staff strove to create a meal situation that was as natural and independent as possible. Measures taken to ensure collective dining and independent eating, e.g., cups and special cutlery. One participant did not want to eat in the dining area and had to be pushed to. After exposure to the dining area, she seemed satisfied. One patient had reacted to the table manners of a fellow patient. Some patients helped others at the table. Those with more severe physical conditions felt that they could not reach their own standards of behaviour at the table and found it difficult to eat in the common dining room. Found more freedom eating privately. Those with moderate eating problems all wanted to eat in the dining room. Despite some silence at the table, patients felt an affinity with others. Some reported unpleasant behaviours at the table. Those able to eat with ease said that their experiences depended to a great extent on the behaviour of others, which varied from positive to negative. |

| Sidenvall 1999 [49] | Rehabilitation and long-term care clinic with four wards, Sweden | To examine and explain the institutional organization of meals, drawing on Goffman’s theory of institutionalized culture, Elias’s theory of the ‘civilising process’, Douglas’s theory of purity and order, and Bourdieu’s key concept ‘habitus’. | Qualitative | Informal ethnographic interviews and participant observations | Older patients with varying conditions | 1st period: 13 elderly women, 5 elderly men, and their respective personal nurses 2nd period: 23 elderly women and 19 elderly men were interviewed twice. A total of 7 registered nurses and 17 enrolled nurses interviewed. The mean age of the patients studied during the first research period was 81.5 years; during the second period, 76.5 years | 84 | In the dining room, patients moved when nurses decided it would be better if they were in a more isolated area of the room or their own rooms—e.g., if they ate with their fingers or shouted or swore. Nurses wanted to create a homelike atmosphere. | Almost none of the caregivers working in the dining room asked the patients about their experiences of being there. Those who failed to eat according to their standards, i.e., their civilized manners, which before hospitalization was their habitus, felt shame and kept silent about their failure. |

| Sundal 2020 [62] | Norwegian general paediatric unit | To explore the experiences of parents and nurses and the concrete ways in which nurses and parents collaborate in partnership when caring for hospitalized preschool children | Qualitative | Participant observation and interviews | The children were in the beginning stages of hospitalization, probably staying for 2 days or more. They were neither critically nor terminally ill, and were between 1 and 6 years old. Eight girls and three boys with various medical diagnoses, four of whom had chronic medical conditions (2 × 1-year-old, 4 × 2-year-old, 4 × 3-year-old, and 1 × 6-year-old). | 12 parents (3 fathers and 9 mothers) of 11 hospitalised children and 17 female nurses participated. | 29 | Optional dining room/bedside eating | >Talks about a mother and child both eating at a table together. >Staff perspectives around the impact of parents on the child’s wellness and eating behaviour. >Parents play an important role in making the meal familiar to the child. |

| Sundal 2023 [47] | A paediatric unit in a Norwegian hospital | To investigate how parents and nurses experience collaborating and sharing responsibilities and tasks when providing home-like care for hospitalized children in everyday situations | Qualitative | Participant observation | Children between the ages of 1 and 6 years with various medical diagnoses | Twelve parents of eleven hospitalized children and 17 nurses who cared for the children | 29 | Parents and families given the option of eating in the dining room together or in their own rooms. | -Option of eating together in their own dining room created an idea of homeliness and familiarity. -One child did not want to eat in bed and wanted to eat at the table. |

| Walton 2013 [45] | Aged care rehabilitation centres in three Australian hospitals | To (1) describe ward activities which have a positive or negative influence on dietary intakes, (2) determine the times taken to start and complete meals, and (3) make recommendations that would make the ward environment more conducive to eating at mealtimes. | Mixed methods | Interview administered questionnaires and participant observation | Observations: 14 male and 16 female patients were observed, and their activities documented. The mean age was 79.2 years. Interviews: 11 patients | Patients, 10 nurses, and 1 doctor | 41 | Bedside meals vs dining rooms. Two hospitals had dining rooms, and the other did not. | >The primary eating location was the bedside. However, when available, a dining room was very popular for mobile patients at lunch and teatime. >Improved socialisation between patients and staff was certainly observed in this study at the two hospitals, which had a dining room. >The private hospital provided patients with their meals one course at a time, with all plate covers removed, and plates from earlier courses were cleared as they were finished. The dietary intakes seemed higher for some patients in the private hospital dining room. The social approach to the meal, the number of decanted food and beverage items, the ambience of the setting, and the additional mealtime assistance afforded by the private hospital were certainly conducive to enhanced mealtime enjoyment and dietary intakes. >Positive interruptions included social interaction, which improved consumption. >Makes recommendations for the use of the dining room. |

| Wright 2006 [30] | Charing Cross Hospital, London. Elderly acute wards | To investigate the effect of eating in a supervised dining room on nutritional intake and weight, for elderly patients in the acute medicine for the elderly ward. | Quantitative | Food intake and weight data were collected over the study period for each patient. | 30 patients attended the ward dining room at lunchtime; 18 patients acted as the control group, eating at their bedside. The median age was 84 years, and there was no significant difference for age, gender, diagnosis, or initial weight between the control and dining room groups. Each patient visited the dining room a median of four times (interquartile range: 2–7). | Patients | 30 | The dining room was established in one ward, and patients were encouraged to attend every lunchtime during weekdays. Patients in the second ward only ate at their bedside and acted as a control group. | >Dining room group had significantly higher intakes of energy than the control group. >Mean energy intake from the lunch meal for the dining group was 489 kcal (438–554), and the mean energy intake for the control group was 360 kcal (289–448). >No significant increase in weight gain or protein intake. imitation: The median number of times visiting the dining room was 4. |

| Young 2024 [60] | Five acute care wards in a metropolitan teaching hospital in Brisbane, Australia (general and renal medicine; general urological and vascular surgery) | To gather and understand the experience of hospital mealtimes from the perspectives of those receiving and delivering mealtime care (older inpatients, caregivers, and staff) using photovoice methods to identify touchpoints and themes to inform the co-design of new mealtime interventions | Qualitative | Photo-voice method | Older patients with varying conditions | Older inpatients, caregivers, and staff directly involved in mealtime care. Overall, 21 participants (10 patients, 5 caregivers, and 6 staff) took part in observations, and 13 participated in interviews (4 patients, 3 caregivers, and 6 staff) | 21 | Eating usually in bed or at the bedside | >Ideal scenario—the environment would be as homely as possible, with the patient tables being clean and cleared of clutter, and the patient would be sitting in a chair. >All agreed that the ideal mealtime would involve and welcome families and caregivers, with caregivers appreciative of also being provided with a meal, conviviality = ideal, reality = isolation |

| Population | (child*) OR (adolescent*) OR (“young W/3 people”) OR (“young W/3 person”) OR (teen*) OR (“young W/3 adult”) OR (“young W/3 adults”) OR (kids) OR (youth) OR (famil*) OR (parent*) OR (“school W/3 age”) OR (minor*) OR (“patient*”) OR (“inpatient*”) |

| Concept | ((“hospital”) OR (“hospital W/3 ward”) OR (“medical W/3 ward”) OR (“pediatric W/3 unit”) OR (“paediatric W/3 unit”) OR (“hospital W/3 care”) OR (“subacute W/3 care”) OR (“acute W/3 care”) OR (“oncology W/3 unit”) OR (“children’s W/3 ward”) OR (“pediatric W/3 care”) OR (“paediatric W/3 care”) OR (“young people’s W/3 ward”) OR (“young person’s W/3 ward”) OR (“ward”) OR (“hospital W/3 unit”) OR (“pediatric W/3 ward”) OR (“ENT W/3 unit”) OR (“gastroenterology W/3 unit”) OR (“surgery W/3 ward”) OR (“orthopaedic W/3 unit”) OR (“orthopedic W/3 unit”) OR (“physiotheraphy W/3 unit”) OR (“physiotheraphy W/3 ward”)) |

| Context | ((“social W/3 eating”) OR (“social W/3 dining”) OR (“social W/3 tables”) OR (“social W/3 table”) OR (“communal W/3 dining”) OR (“collective W/3 dining”) OR (“eating W/3 together”) OR (“dining W/3 together”) OR (“sharing W/3 food”) OR (“shared W/3 mealtimes”) OR (“shared W/3 mealtime”) OR (“sociable W/3 eating”) OR (“sociable W/3 mealtimes”) OR (“sociable W/3 mealtime”) OR (“family-style W/3 meals”) OR (“family-style W/3 meal”) OR (“eating W/3 alone”) OR (“solitary W/3 eating”) OR (“solitary W/3 dining”) OR (“commensal W/3 eating”) OR (mealtime*) OR (commensa*) OR (“communal W/3 table”) OR (“family-style W/3 dining”) OR (“group W/3 dining”) OR (“food W/3 service”) OR (“eating W/3 environment”) OR (“eating W/3 location”)) |

References

- Maharaj, J. Take Back the Tray: Revolutionizing Food in Hospitals, Schools and Other Institutions; ECW Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, K. Serving the Public: The Good Food Revolution in Schools, Hospitals and Prisons; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shelley, P. Report of the Independent Review of NHS Hospital Food. Department of Health and Social Care. 2020. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5f930458d3bf7f35e85fe7ff/independent-review-of-nhs-hospital-food-report.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- The Patients Association. NHS Hospital Food Survey. Department of Health and Social Care. 2020. Available online: https://www.patients-association.org.uk/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=2606dce9-399e-4b4c-b3b6-6ff9af13642d (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Stockbridge, M.D.; Bahouth, M.N.; Zink, E.K.; Hillis, A.E. Socialize, Eat More, and Feel Better: Communal Eating in Acute Neurological Care. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 102, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, J.; Haines, T.P.; Truby, H. The efficacy of Protected Mealtimes in hospitalised patients: A stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischler, C. Food, self and identity. Soc. Sci. Inf. 1988, 27, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M. Deciphering a Meal. Daedalus 1972, 101, 61–81. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20024058 (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Fischler, C. Commensality, Society and Culture. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2011, 50, 528–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnwall, A.; Colombo, P.E.; Sydner, Y.M.; Neuman, N. The impact of eating alone on food intake and everyday eating routines: A cross-sectional study of community-living 70- to 75-year-olds in Sweden. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oostindjer, M.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Wang, Q.; Skuland, S.E.; Egelandsdal, B.; Gro, V.; Amdam Schjoll, A.; Pachuki, M.C.; Rozin, P.; Stein, J.; et al. Are school meals a viable and sustainable tool to improve the healthiness and sustainability of children’s diet and food consumption? A cross-national comparative perspective. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 57, 3942–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrer, N.; Mcintosh, I.; Punch, S.; Emond, R. Children and food practices in residential care: Ambivalence in the ‘institutional’ home. Child. Geogr. 2010, 8, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I. Children’s Experiences of Hospitalization. J. Child. Health Care 2006, 10, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelander, T.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Quality in pediatric nursing care: Children’s expectations. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 2004, 27, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, L.A.; Seitz, M. Through Their Words: Sources of Bother for Hospitalized Children and Adolescents with Cancer. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 34, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boztepe, H.; Çınar, S.; Ay, A. School-age children’s perception of the hospital experience. J. Child. Health Care 2017, 21, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H.J.; Fletcher, K.E. The Hospital Experience Through the Patients’ Eyes. J. Patient Exp. 2020, 7, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karhe, L.; Kaunonen, M. Patient Experiences of Loneliness: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2015, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, É.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobal, J.; Nelson, M.K. Commensal eating patterns: A community study. Appetite 2003, 41, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brannen, J.; O’Connell, R.; Mooney, A. Families, meals and synchronicity: Eating together in British dual earner families. Community Work. Fam. 2013, 16, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, H.; Michaud, M.; Neuman, N. What Is Commensality? A Critical Discussion of an Expanding Research Field. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skafida, V. The family meal panacea: Exploring how different aspects of family meal occurrence, meal habits and meal enjoyment relate to young children’s diets. Sociol. Health Illn. 2013, 35, 906–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Rosario, V.A.; Walton, K. Hospital Food Service. In Handbook of Eating and Drinking; Meiselman, H., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, S.; Thomas, A. Steps for Conducting a Scoping Review. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2022, 14, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptiste, F.; Egan, M.; Dubouloz-Wilner, C.J. Geriatric rehabilitation patients’ perceptions of unit dining locations. Can. Geriatr. J. 2014, 17, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovski, K.; Nenov, A.; Ottaway, A.; Skinner, E. Does eating environment have an impact on the protein and energy intake in the hospitalised elderly? Nutr. Diet. 2017, 74, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.; Hickson, M.; Frost, G. Eating together is important: Using a dining room in an acute elderly medical ward increases energy intake. J. Human Nutr. Dietetics 2006, 19, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.; Hartwell, H. A comparison of energy intake between eating positions in a NHS hospital—A pilot study. Appetite 2004, 43, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosbergen, I.C.; Grimley, R.S.; Hayward, K.S.; Brauer, S.G. The impact of environmental enrichment in an acute stroke unit on how and when patients undertake activities. Clin. Rehabil. 2019, 33, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melin, L.; Götestam, K.G. The effects of rearranging ward routines on communication and eating behaviors of psychogeriatric patients. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1981, 14, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.D.M.; Snaith, P.A. The social behaviour of geriatric patients at mealtimes: An observational and an intervention study. Age Ageing 1980, 9, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, H.J.; Shepherd, P.A.; Edwards, J.S. Effects of a hospital ward eating environment on patients’ mealtime experience: A pilot study. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 70, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, M.; Beermann, T.; Mortensen, M.N.; Skadhauge, L.B.; Køhler, M.; Lindorff-Larsen, K.; Rasmussen, H.H. Optimizing protein and energy intake in hospitals by improving individualized meal serving, hosting and the eating environment. Nutrition 2017, 34, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiesen, S.L.; Aadal, L.; Uldbæk, M.L.; Astrup, P.; Byrne, D.V.; Wang, Q.J. Music Is Served: How Acoustic Interventions in Hospital Dining Environments Can Improve Patient Mealtime Wellbeing. Foods 2021, 10, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, M.; Birkelund, R.; Poulsen, I.; Martinsen, B. Supporting existential care with protected mealtimes: Patients’ experiences of a mealtime intervention in a neurological ward. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1947–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Martinsen, B.; Birkelund, R.; Poulsen, I. Raising a beautiful swan: A phenomenological-hermeneutic interpretation of health professionals’ experiences of participating in a mealtime intervention inspired by Protected Mealtimes. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2017, 12, 1360699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gardner, L.; Trueman, H. Improving mealtimes for patients and staff within an eating disorder unit: Understanding of the problem and first intervention during the pandemic—An initial report. BMJ Open Qual. 2021, 10, e001366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, L.; Tillier, K.; Marshall-Tyson, K.; Trueman, H.; Hunt, D.F. Improving mealtimes for patients and staff within an eating disorder unit: The next chapter. BMJ Open Qual. 2022, 11, e001955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidenvall, B.; Fjellstrom, C.; Christina, A. The meal situation in geriatric care—intentions and experiences. J. Adv. Nurs. 1994, 20, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquet, C.; St-Arnaud-McKenzie, D.; Ma, Z.; Kergoat, M.-J.; Ferland, G.; Dubé, L. More than just not being alone: The number, nature, and complementarity of meal-time social interactions influence food intake in hospitalized elderly patients. Gerontologist 2008, 48, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, A.; Welch, C.; Ager, L.; Costar, A. Hospital mealtimes: Action research for change? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2005, 64, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, K.; Williams, P.; Tapsell, L.; Hoyle, M.; Shen, Z.W.; Gladman, L.; Nurka, M. Observations of mealtimes in hospital aged care rehabilitation wards. Appetite 2013, 67, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mårtensson, U.; Nolbris, M.J.; Mellgren, K.; Wijk, H.; Nilsson, S. The five aspect meal model as a conceptual framework for children with a gastrostomy tube in paediatric care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 35, 1352–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundal, H. Home-like care: Collaboration between parents and nurses in everyday situations when children are hospitalized. J. Child. Health Care 2023, 28, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Poulsen, I.; Martinsen, B.; Birkelund, R. Longing for homeliness: Exploring mealtime experiences of patients suffering from a neurological disease. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidenvall, B. Meal procedures in institutions for elderly people: A theoretical interpretation. J. Adv. Nurs. 1999, 30, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryon, E.; de Casterlé, B.D.; Gastmans, C.; Steeman, E.; Milisen, K. Mealtime care on a geriatric- psychiatric ward from the perspective of the caregivers: A qualitative case study design. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2008, 29, 471–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidenvall, B.; Fjellström, C.; Ek, A.-C. Cultural perspectives of meals expressed by patients in geriatric care. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 1996, 33, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Wallis, D.; Leung, N.; Meyer, C. “All eyes are on you”: Anorexia nervosa patient perspectives of in-patient mealtimes. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furness, K.; Harris, M.; Lassemillante, A.; Keenan, S.; Smith, N.; Desneves, K.J.; King, S. Patient Mealtime Experience: Capturing Patient Perceptions Using a Novel Patient Mealtime Experience Tool. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, K.L.; Schjøtler, B.; Melgaard, D. Patients’ experiences eating in a hospital–A qualitative study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 45, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, J.; Porter, J.; Palermo, C.; Ottrey, E. Meals beyond the bedside: An ethnographic exploration of staffs’ perspectives and experiences of communal dining in subacute care. Nurs. Health Sci. 2021, 23, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justesen, L.; Mikkelsen, B.E.; Gyimóthy, S. Understanding hospital meal experiences by means of participant-driven-photo-elicitation. Appetite 2014, 75, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, M.; Birkelund, R.; Poulsen, I.; Martinsen, B. Hospital meals are existential asylums to hospitalized people with a neurological disease: A phenomenological–hermeneutical explorative study of the meaningfulness of mealtimes. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, S.; Wallis, D.J.; Leung, N.; Arcelus, J.; Meyer, C. Mealtimes on eating disorder wards: A two-study investigation. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, A.-S.; Nyberg, M. Hospitality through negotiations: The performing of everyday meal activities among nursing staff and meal hosts. A qualitative study. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 27, 100478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.M.; Byrnes, A.; Mahoney, D.; Power, G.; Cahill, M.; Heaton, S.; McRae, P.; Mudge, A.; Miller, E. Exploring hospital mealtime experiences of older inpatients, caregivers and staff using photovoice methods. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 1906–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottrey, E.; Porter, J.; Huggins, C.E.; Palermo, C. “Meal realities”—An ethnographic exploration of hospital mealtime environment and practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 74, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundal, H.; Vatne, S. Parents’ and nurses’ ideal collaboration in treatment-centered and home-like care of hospitalized preschool children—A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2020, 19, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neo, Y.L.; Hong, L.I.; Chan, E.Y. Enrolled nurses’ perceptions of providing nutritional care to hospitalised older people in Singapore’s acute care setting: A qualitative descriptive study. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2020, 16, e12354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, H.J.; Shepherd, P.A.; Edwards, J.S.; Johns, N. What do patients value in the hospital meal experience? Appetite 2016, 96, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justesen, L.; Gyimóthy, S.; Mikkelsen, B.E. Hospitality within hospital meals—Socio-material assemblages. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnwall, A.; Sydner, Y.M.; Koochek, A.; Neuman, N. Eating Alone or Together among Community-Living Older People—A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dornan, M.; Semple, C.; Moorhead, A.; McCaughan, E. A qualitative systematic review of the social eating and drinking experiences of patients following treatment for head and neck cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 4899–4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelock, G.; Edoardo, A. Effectiveness of mealtime interventions to improve nutritional intake of adult patients in the acute care setting: A systematic review. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2013, 11, 263–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.; Carrier, J.; Hopkinson, J. Assistance at mealtimes in hospital settings and rehabilitation units for patients (>65 years) from the perspective of patients, families and healthcare professionals: A mixed methods systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 69, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, S.; Curtis, S.; Diez-Roux, A.; Macintyre, S. Understanding and representing ‘place’ in health research: A relational approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 1825–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, M. Children’s Pictures of a Good and Desirable Meal in Kindergarten—A Participatory Visual Approach. Child. Soc. 2019, 33, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.; Wills, W. Institutional spaces and sociable eating: Young people, food and expressions of care. J. Youth Studies 2020, 24, 580–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardono, P.; Hibino, H.; Koyama, S. Effects of Restaurant Interior Elements on Social Dining Behavior. Asian J. Environ. Stud. 2011, 2, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; McCutcheon, H. Mealtimes in hospital–who does what? J. Clin. Nurs. 2006, 15, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pill, R. An apple a day… Some reflections on Working Class Mothers’ Views of Food and Health. In The Sociology of Food and Eating: Essays on the Sociological Significance of Food; Murcott, A., Ed.; Gower: Aldershot, UK, 1983; pp. 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Dornan, M.; Semple, C.; Moorhead, A. Experiences and perceptions of social eating for patients living with and beyond head and neck cancer: A qualitative study. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 4129–4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S. Food avoidance in patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy. Support. Care Cancer 1993, 1, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, R.; Horn, H.; Erickson, J.M. Eating experiences of children and adolescents with chemotherapy-related nausea and mucositis. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2010, 27, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mårtensson, U. Children and Their Parents’ Experiences of Mealtimes When the Child Lives with a Gastrostomy Tube. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2022. Available online: https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/handle/2077/70523/Ulrika%20M%C3%A5rtensson_SG_Inlaga_utan%20artiklar.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Pollock, D.K.; Khalil, H.; Evans, C.; Godfrey, C.; Pieper, D.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; McInerney, P.; Peters, M.D.J.; Klugar, M.; et al. The role of scoping reviews in guideline development. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2024, 169, 111301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, B.; Coster, W.; Snethen, G.; Derstine, M.; Piller, A.; Tucker, C. Caregivers’ Perspectives on the Sensory Environment and Participation in Daily Activities of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2017, 71, 7104220020p1–7104220028p9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, R.; Thompson, C.; Brock, J.; Barnes, M. ‘Food What Makes Me Happy’: The Meaning and Purposes of ‘Good Food’ for Children in Hospital. British Sociological Association Annual Conference, Manchester. 2025. Available online: https://www.britsoc.co.uk/media/26842/ac2025_abstract_book_24april25.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Moody, K.; Meyer, M.; Mancuso, C.A.; Charlson, M.; Robbins, L. Exploring concerns of children with cancer. Support. Care Cance 2006, 14, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, V.; Coad, J.; Hicks, P.; Glacken, M. Social spaces for young children in hospital. Child. Care Health Dev. 2014, 40, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moal, F.; Michaud, M.; Hartwick-Pflaum, C.A.; Middleton, G.; Mallon, I.; Coveney, J. Beyond the Normative Family Meal Promotion: A Narrative Review of Qualitative Results about Ordinary Domestic Commensality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Hannan, P.J.; Story, M.; Croll, J.; Perry, C. Family meal patterns: Associations with sociodemographic characteristics and improved dietary intake among adolescents. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003, 103, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murcott, A. Family meals—A thing of the past? In Food, Identity and Health; Caplan, P., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmann, E. Family-centered care: Shifting orientation. Pediatr. Nurs. 1994, 20, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, R.; Godfrey, M.; Young, J. The impacts of family involvement on general hospital care experiences for people living with dementia: An ethnographic study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 96, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.J.; Lee, L.A.; Carnevale, F.A.; Crump, L.; Garros, D.; O’Hearn, K.; Curran, J.A.; Fiest, K.M.; Fontela, P.; Moghadam, N.; et al. Parental and family presence are essential: A qualitative study of children’s lived experiences with family presence in pediatric intensive care. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2025, 80, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekra, E.M.; Gjengedal, E. Being hospitalized with a newly diagnosed chronic illness--a phenomenological study of children’s lifeworld in the hospital. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2012, 17, 18694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, F.; Shipway, L.; Barry, A.; Taylor, R.M. What’s it like when you find eating difficult: Children’s and parents’ experiences of food intake. Cancer Nurs. 2012, 35, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barnes, E.; O’Connell, R.; Thompson, C.; Brock, J.; Heyes, C.; Bostock, N. Social Eating Among Child and Adult Hospital Patients: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050796

Barnes E, O’Connell R, Thompson C, Brock J, Heyes C, Bostock N. Social Eating Among Child and Adult Hospital Patients: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050796

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarnes, Emily, Rebecca O’Connell, Claire Thompson, Jessica Brock, Caroline Heyes, and Nancy Bostock. 2025. "Social Eating Among Child and Adult Hospital Patients: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050796

APA StyleBarnes, E., O’Connell, R., Thompson, C., Brock, J., Heyes, C., & Bostock, N. (2025). Social Eating Among Child and Adult Hospital Patients: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 796. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050796