The Impact of Physical Activity on Long COVID Symptoms Among College Students: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Questionnaire and Variables:

2.3. Physical Activity

2.4. Long COVID Symptoms

2.5. Symptoms During the Acute COVID-19 Infection

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

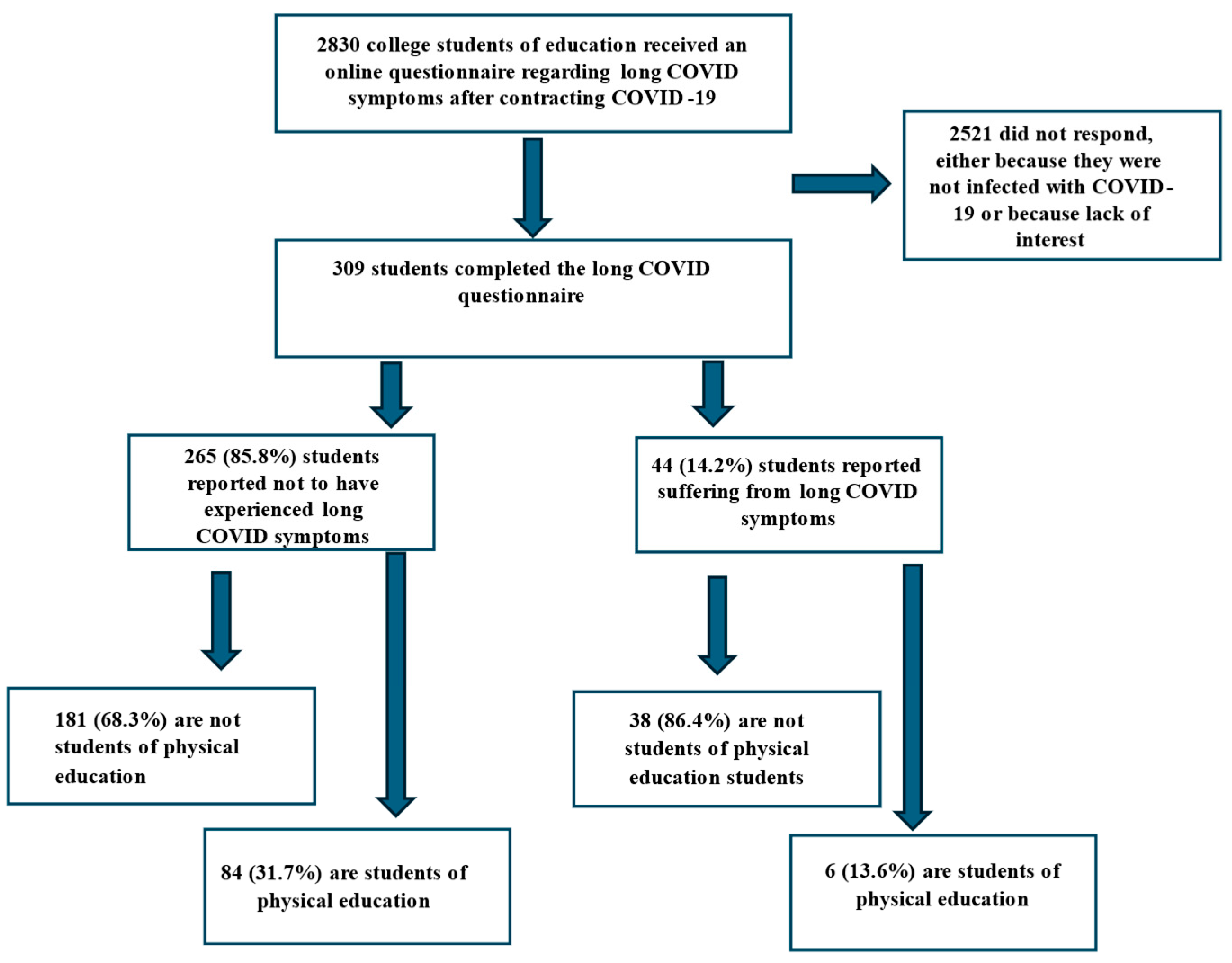

Research Sample

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Corona (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeßle, J.; Waterboer, T.; Hippchen, T.; Simon, J.; Kirchner, M.; Lim, A.; Müller, B.; Merle, U. Persistent Symptoms in Adult Patients 1 Year After Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2022, 74, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 Condition; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 6 February 2024; Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Subramanian, A.; Nirantharakumar, K.; Hughes, S.; Myles, P.; Williams, T.; Gokhale, K.M.; Taverner, T.; Chandan, J.S.; Brown, K.; Simms-Williams, N.; et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long—COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re’em, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Henriksson, M.; Wall, A.; Nyberg, J.; Adiels, M.; Lundin, K.; Bergh, Y.; Åberg, M. Effects of exercise on symptoms of anxiety in primary care patients: A randomized controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 26–34, Erratum in J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 299, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.J.; Merwin, R.M. The Role of Exercise in Management of Mental Health Disorders: An Integrative Review. Annu. Rev. Med. 2021, 72, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R.J.; Campbell, J.P.; Gleeson, M.; Krüger, K.; Nieman, D.C.; Pyne, D.B.; Turner, J.E.; Walsh, N.P. Can exercise affect immune function to increase susceptibility to infection? Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 26, 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, N.P.; Gleeson, M.; Pyne, D.B.; Nieman, D.C.; Dhabhar, F.S.; Shephard, R.J.; Oliver, S.J.; Bermon, S.; Kajeniene, A. Position statement. Part two: Maintaining immune health. Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 17, 64–103. [Google Scholar]

- Nieman, D.C.; Sakaguchi, C.A. Physical activity lowers the risk for acute respiratory infections: Time for recognition. J. Sport Health Sci. 2022, 11, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casuso, R.A.; Huertas, J.R. Mitochondrial Functionality in Inflammatory Pathology-Modulatory Role of Physical Activity. Life 2021, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastin, S.F.M.; Abaraogu, U.; Bourgois, J.G.; Dall, P.M.; Darnborough, J.; Duncan, E.; Dumortier, J.; Pavón, D.J.; McParland, J.; Roberts, N.J.; et al. Effects of Regular Physical Activity on the Immune System, Vaccination and Risk of Community-Acquired Infectious Disease in the General Population: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Lan, W.; Yang, G.; Yan, L.; Xiang, J.; Lan, C.; Yan, Z.; Shanshan, L. Exercise Intervention in Treatment of Neuropsychological Diseases: A Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 569206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimeno-Almazán, A.; Pallarés, J.G.; Buendía-Romero, Á.; Martínez-Cava, A.; Franco-López, F.; Martínez, B.J.S.-A.; Bernal-Morel, E.; Courel-Ibáñez, J. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome and the Potential Benefits of Exercise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feter, N.; Caputo, E.L.; Delpino, F.M.; Leite, J.S.; da Silva, L.S.; de Almeida Paz, I.; Santos Rocha, J.Q.; Vieira, Y.P.; Schröeder, N.; da Silva, C.N.; et al. Physical activity and long COVID: Findings from the Prospective Study About Mental and Physical Health in Adults cohort. Public Health 2023, 220, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimeno-Almazán, A.; Martínez-Cava, A.; Buendía-Romero, Á.; Franco-López, F.; Sánchez-Agar, J.A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Tufano, J.J.; Pallarés, J.G.; Courel-Ibáñez, J. Relationship between the severity of persistent symptoms, physical fitness, and cardiopulmonary function in post-COVID-19 condition. A population-based analysis. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 2199–2208, Erratum in Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, E.; Fancourt, D. Health behaviours the month prior to COVID-19 infection and the development of self-reported long COVID and specific long COVID symptoms: A longitudinal analysis of 1581 UK adults. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, Z.; Lu, S. Baseline physical activity and the risk of severe illness and mortality from COVID-19: A dose-response meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 32, 102130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, W.P.; Goodwill, A.M. Can exercise attenuate the negative effects of long COVID syndrome on brain health? Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 986950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norweg, A.; Yao, L.; Barbuto, S.; Nordvig, A.S.; Tarpey, T.; Collins, E.; Whiteson, J.; Sweeney, G.; Haas, F.; Leddy, J. Exercise intolerance associated with impaired oxygen extraction in patients with long COVID. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2023, 313, 104062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Joseph, G.; Schori, H. The beneficial effect of the first COVID-19 lockdown on undergraduate students of education: Prospective cohort study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e27286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, G.; Margalit, I.; Weiss-Ottolenghi, Y.; Rubin, C.; Murad, H.; Gardner, R.C.; Barda, N.; Ben-Shachar, E.; Indenbaum, V.; Gilboa, M.; et al. Persistence of Long COVID Symptoms Two Years After SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Prospective Longitudinal Cohort Study. Viruses 2024, 16, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Ahrnsbrak, R.; Rekito, A. Evidence Mounts That About 7% of US Adults Have had Long COVID. JAMA 2024, 332, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, J.; Bilasy, S.E.; Yang, C.; El-Shamy, A. Exploring the Complexities of Long COVID. Viruses 2024, 16, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laskowski, N.M.; Brandt, G.; Paslakis, G. Minderheiten Gender Inequalities of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Synthesis of Systematic Reviews with a Focus on Sexual and Gender Minorities. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2024, 74, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Cao, M.; Yeung, W.F.; Cheung, D.S.T. The effectiveness of exercise in alleviating long COVID symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2024, 21, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Mei, B.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Wei, G.; Kuang, F.; Li, B.; Su, S. Prevalence and risk factors for persistent symptoms after COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Age, (median, (min, max)) | 26, (19, 57) |

| Gender, female (N, %) | 257, 83.2% |

| Status, single (N, %) | 213. 68.9% |

| Study year (N, %) | |

| 1st year | 71, 23.0% |

| 2nd year | 63, 20.4% |

| 3rd year | 80, 25.9% |

| 4th year | 26, 8.4% |

| Other (M.Ed. studies/supplementing) | 69, 22.3% |

| Students from disciplines other than physical education (N, %) | 219, 70.9% |

| Contracted COVID-19 once (N, %) | 224, 72.5% |

| Infected during the Omicron outbreak (N, %) | 215, 69.6% |

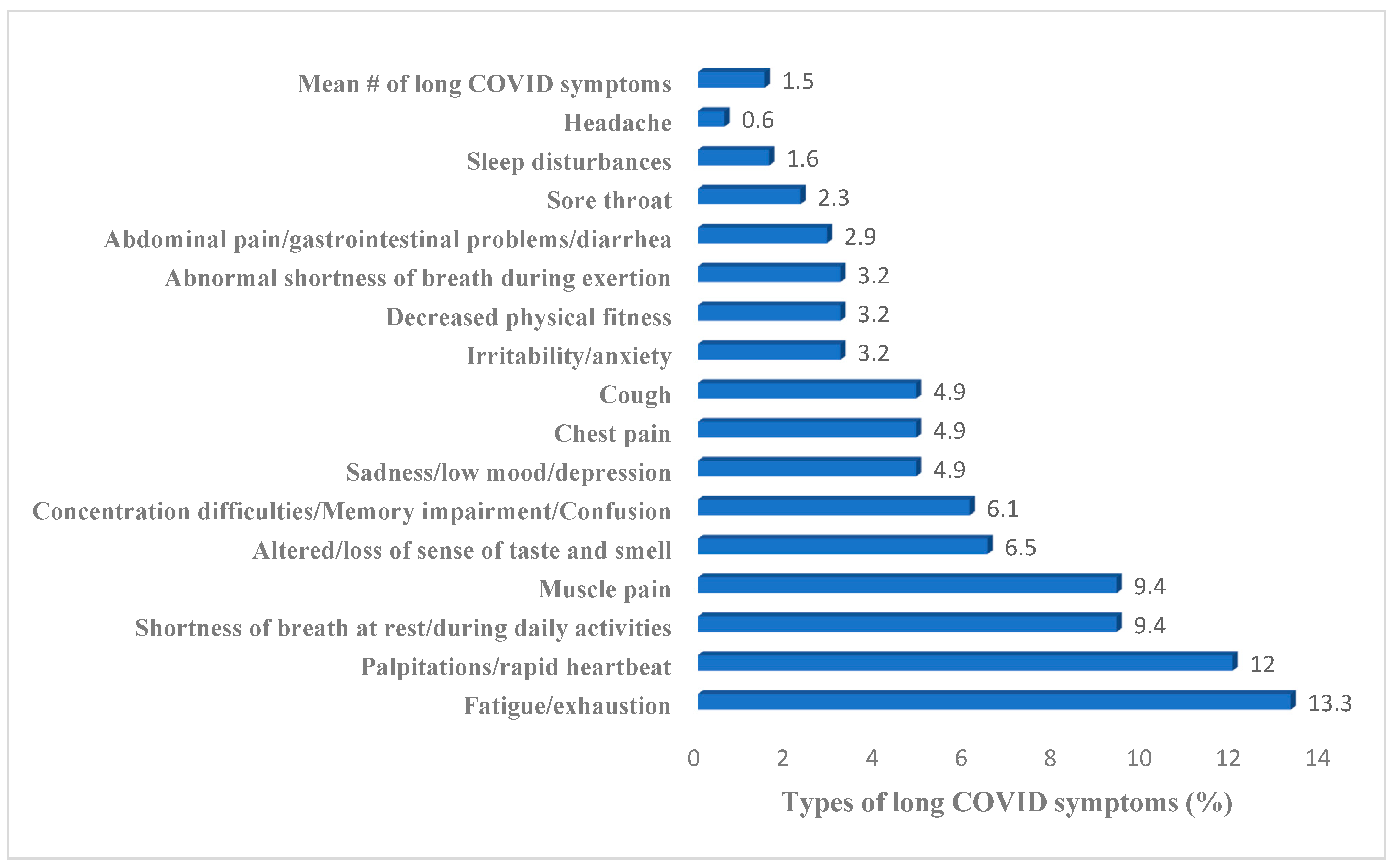

| Number of symptoms during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection (mean, SD) | 1.53, 0.22 |

| Students reporting to be suffering from long COVID symptoms (N, %) | 44/309, 14.24% |

| N | Mean (SD) | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) of long COVID symptoms | |||

| Students who engage in a low level of physical activity | 158 | 1.75 (0.89) | p = 0.376 |

| Students who engage in a high level of physical activity | 151 | 1.83 (0.85) | |

| N | Mean (SD) Time of physical activity (3 = 61–120 min, 4 = 121–240 min) | Sig. | |

| Weekley physical activity time (minutes) of students without symptoms of long COVID | 263 | 3.75 (1.56) | p = 0.26 |

| Weekley physical activity time (minutes) of students with symptoms of long COVID | 44 | 3.86 (1.69) | |

| N | Mean (SD) physical activity time (3 = 31–60 min, 4 = 61–120 min) | Sig. | |

| Weekley amount of physical activity that causes sweating and strenuous breathing (minutes) of students without symptoms of long COVID | 252 | 3.0 (1.5) | p = 0.272 |

| Weekley amount of physical activity that causes sweating and strenuous breathing (minutes) of students with symptoms of long COVID | 40 | 3.28 (1.22) | |

| Students of Physical Education (N, %) | Education students from other disciplines (N, %) | ||

| Students without symptoms of long COVID | 89 (93.3%) | 181 (82.6%) | |

| Students without symptoms of long COVID | 6 (6.7%) | 38 (17.4%) |

| Mean of Acute COVID-19 Infection Symptoms | Mean # of Long COVID Symptoms | Mean # of Times of Physical Activity Per Week | Age | Marital Status | Gender (Female) | Students Not Studying Physical Education Student | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean # of acute COVID-19 infection symptoms | Pearson correlation Sig. (2-tailed) | 1 | 0.492 p < 0.001 | 0.099 p = 0.082 | 0.69 p = 0.228 | 0.66 p = 0.263 | 0.144 p = 0.012 | 0.081 p = 0.155 |

| Mean long COVID symptoms | Pearson correlation Sig. (2-tailed) | 1 | 0.081 p = 0.154 | 0.018 p = 0.751 | 0.66 p = 0.920 | 0.118 p = 0.039 | 0.129 p = 0.024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Joseph, G. The Impact of Physical Activity on Long COVID Symptoms Among College Students: A Retrospective Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050754

Joseph G. The Impact of Physical Activity on Long COVID Symptoms Among College Students: A Retrospective Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050754

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoseph, Gili. 2025. "The Impact of Physical Activity on Long COVID Symptoms Among College Students: A Retrospective Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050754

APA StyleJoseph, G. (2025). The Impact of Physical Activity on Long COVID Symptoms Among College Students: A Retrospective Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050754