The Ability of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-5 to Identify Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder in the General Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

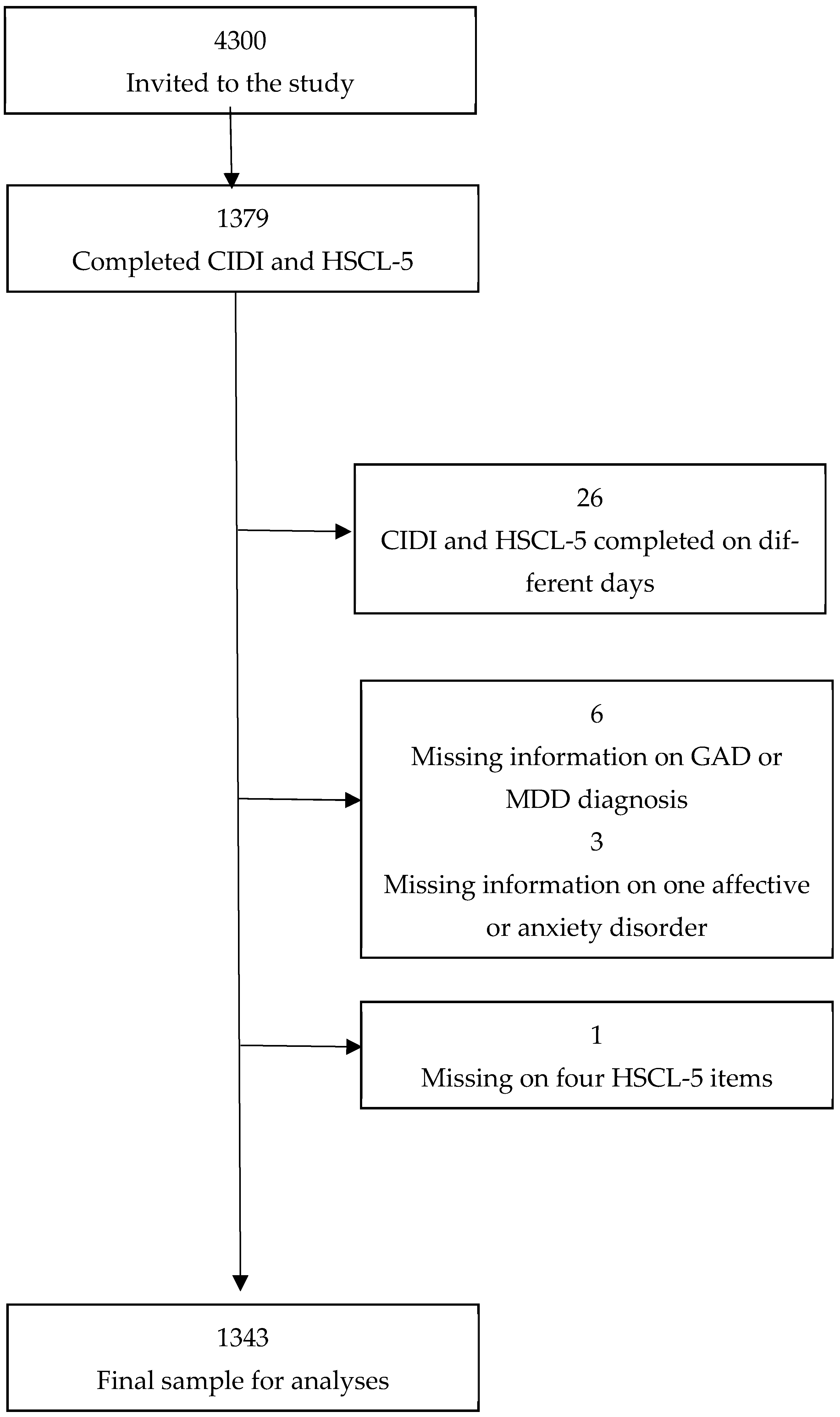

2. Materials and Methods

3. Procedure and Measures

4. Statistical Analyses

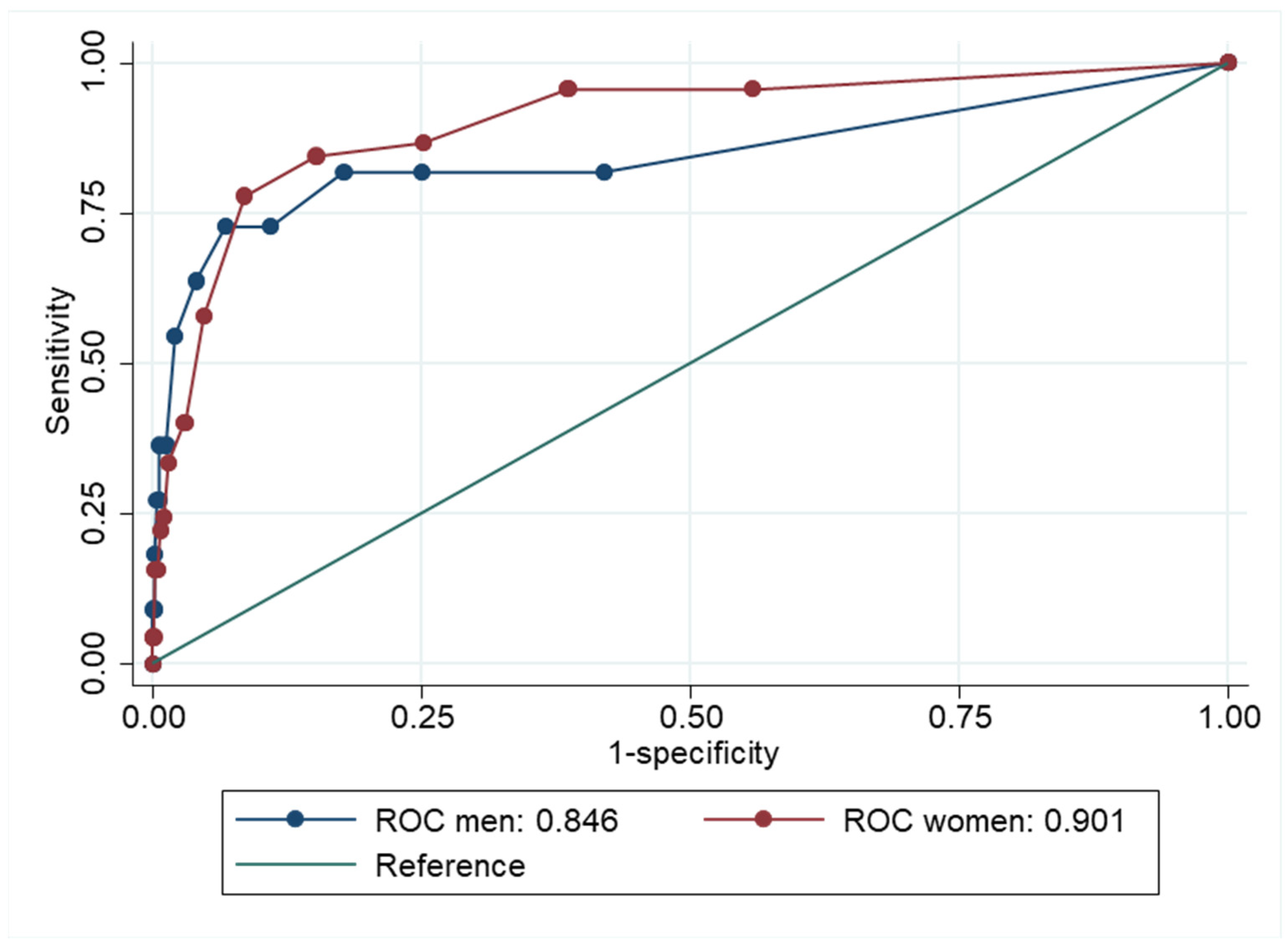

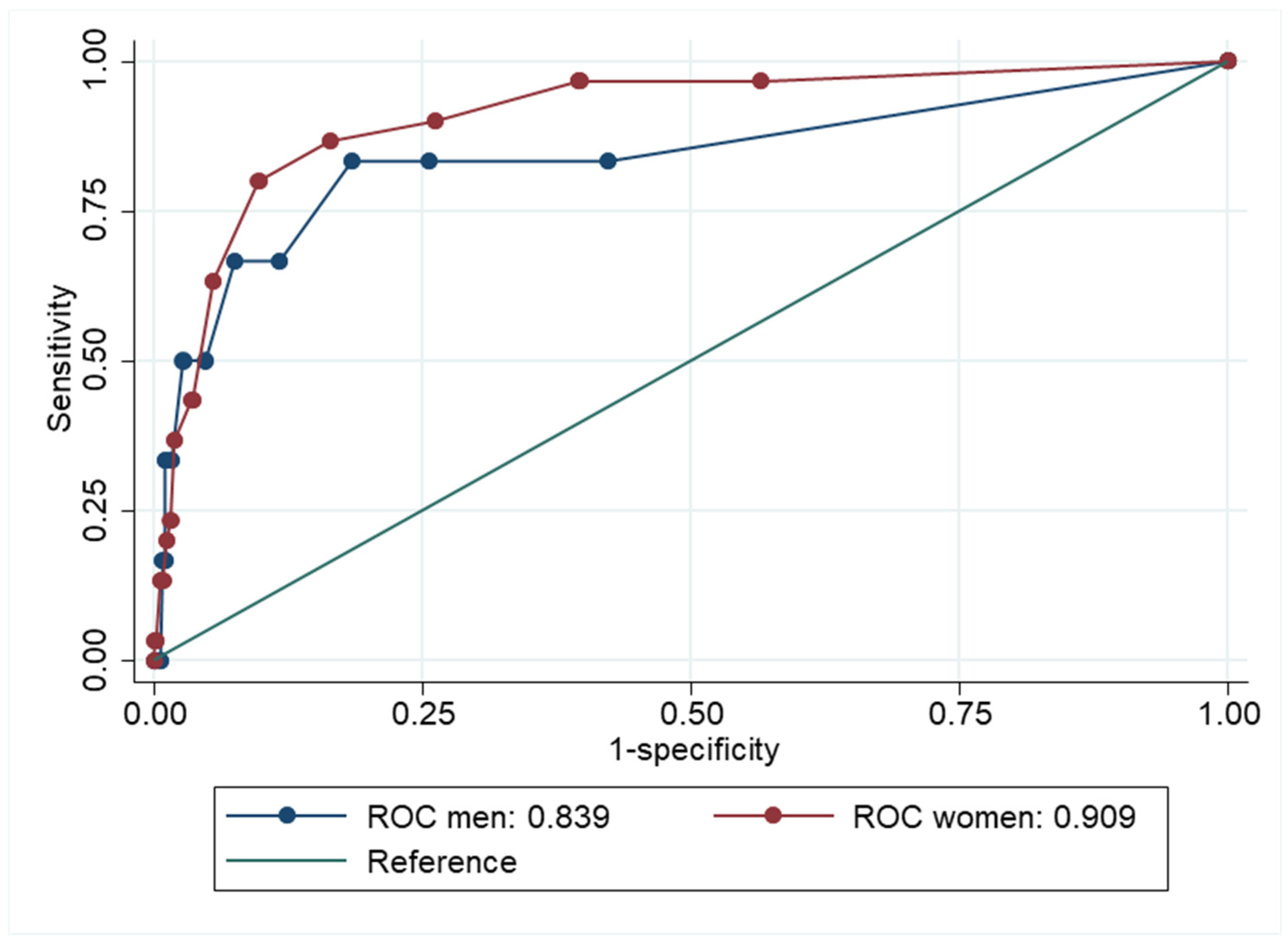

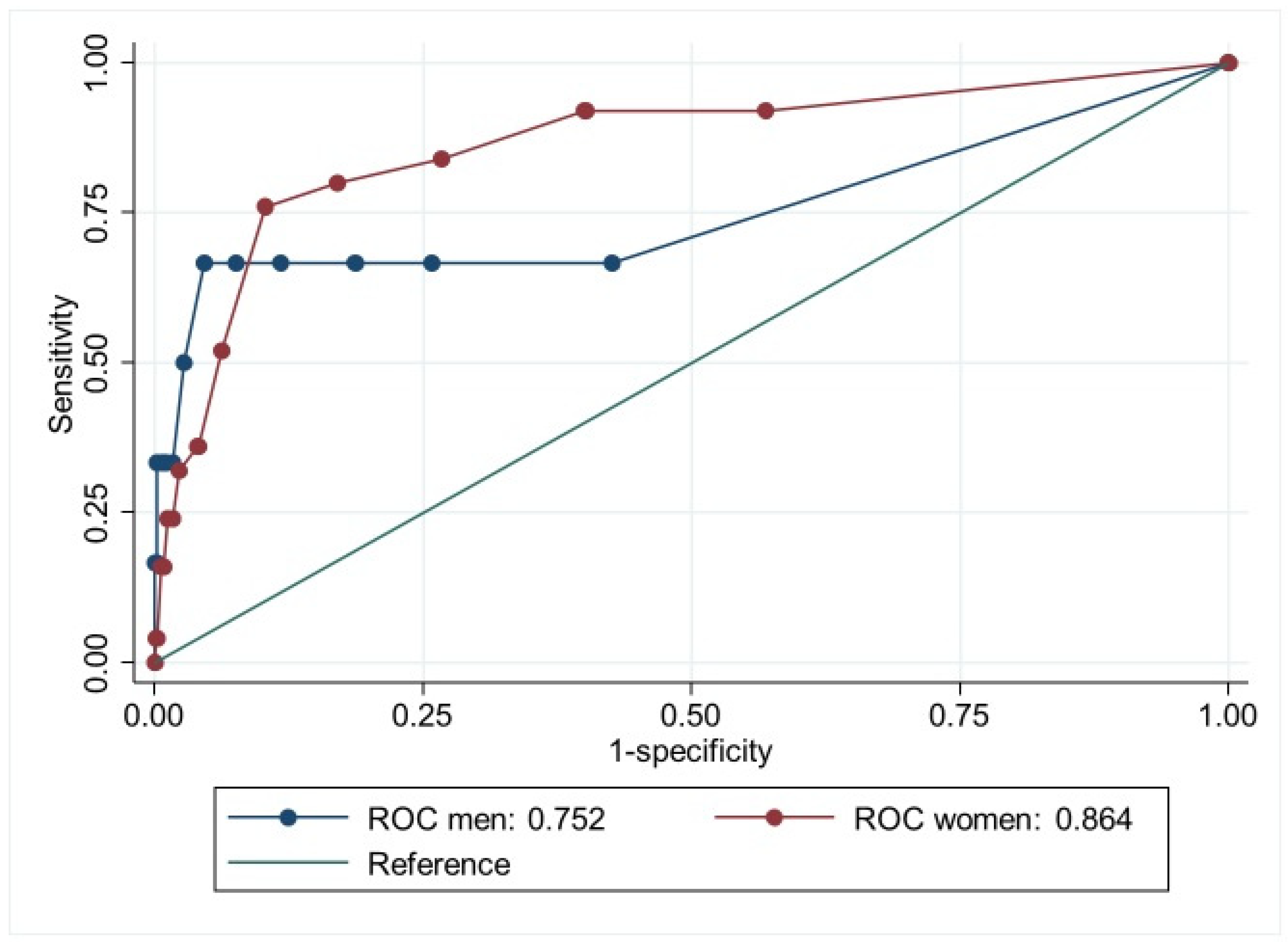

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Strengths and Limitations

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HSCL | The Hopkins Symptom Checklist |

| GAD | generalized anxiety disorder |

| MDD | major depressive disorder |

| CIDI | Composite International Diagnostic Interview |

| HUNT | Trøndelag Health Study |

| ROC | Receiver Operator Characteristics |

| PPV | positive predictive value |

| NPV | negative predictive values |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| DSM-5 | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases 10th edition |

| WMHS | World Mental Health Survey |

| AUC | area under the ROC curve |

References

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K.D. Global burden of disease and the impact of mental and addictive disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokstad, S.; Weiss, D.A.; Krokstad, M.A.; Rangul, V.; Kvaløy, K.; Ingul, J.M.; Bjerkeset, O.; Twenge, J.; Sund, E.R. Divergent decennial trends in mental health according to age reveal poorer mental health for young people: Repeated cross-sectional population-based surveys from the HUNT Study, Norway. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e057654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knapstad, M.; Sivertsen, B.; Knudsen, A.K.; Smith, O.R.F.; Aaro, L.E.; Lonning, K.J.; Skogen, J.C. Trends in self-reported psychological distress among college and university students from 2010 to 2018. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, J.M.; Cooper, A.B.; Joiner, T.E.; Duffy, M.E.; Binau, S.G. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calling, S.; Midlöv, P.; Johansson, S.-E.; Sundquist, K.; Sundquist, J. Longitudinal trends in self-reported anxiety. Effects of age and birth cohort during 25 years. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, T.; Schoon, I.; McMunn, A.; Sacker, A. Mental distress among young adults in Great Britain: Long-term trends and early changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 57, 1261–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, A.J.; Scott, K.M.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.A. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol. Med. 2013, 43, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Andrews, G.; Colpe, L.J.; Hiripi, E.; Mroczek, D.K.; Normand, S.-L.; Walters, E.E.; Zaslavsky, A.M. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 2002, 32, 959–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derogatis, L.R.; Lipman, R.S.; Rickels, K.; Uhlenhuth, E.H.; Covi, L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behav. Sci. 1974, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parloff, M.B.; Kelman, H.C.; Frank, J.D. Comfort, effectiveness, and self-awareness as criteria of improvement in psychotherapy. Am. J. Psychiatry 1954, 111, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandanger, I.; Moum, T.; Ingebrigtsen, G.; Dalgard, O.S.; Sørensen, T.; Bruusgaard, D. Concordance between symptom screening and diagnostic procedure: The Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview I. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 1998, 33, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skogen, J.C.; Øverland, S.; Smith, O.R.; Aarø, L.E. The factor structure of the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL-25) in a student population: A cautionary tale. Scand. J. Public Health 2017, 45, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Barragán, M.; Fernández-San-Martín, M.I.; Clavería-Fontán, A.; Aldecoa-Landesa, S.; Casajuana-Closas, M.; Llobera, J.; Oliván-Blázquez, B.; Peguero-Rodríguez, E. Validation and Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 Scale for Depression Detection in Primary Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veijola, J.; Jokelainen, J.; Läksy, K.; Kantojärvi, L.; Kokkonen, P.; Järvelin, M.-R.; Joukamaa, M. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 in screening DSM-III-R axis-I disorders. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2003, 57, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Kopec, J.A.; Cibere, J.; Li, L.C.; Goldsmith, C.H. Population survey features and response rates: A randomized experiment. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1422–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolstad, S.; Adler, J.; Rydén, A. Response burden and questionnaire length: Is shorter better? A review and meta-analysis. Value Health 2011, 14, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambs, K.; Moum, T. How well can a few questionnaire items indicate anxiety and depression? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1993, 87, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, B.H.; Dalgard, O.S.; Tambs, K.; Rognerud, M. Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: A comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI-5 (SF-36). Nord. J. Psychiatry 2003, 57, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalbach, B.; Zenger, M.; Tibubos, A.N.; Kliem, S.; Petrowski, K.; Brähler, E. Psychometric properties of two brief versions of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist: HSCL-5 and HSCL-10. Assessment 2021, 28, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Barragán, M.; Fernández-San-Martín, M.I.; Clavería, A.; Le Reste, J.Y.; Nabbe, P.; Motrico, E.; Gómez-Gómez, I.; Peguero-Rodríguez, E. Measuring depression in Primary Health Care in Spain: Psychometric properties and diagnostic accuracy of HSCL-5 and HSCL-10. Front. Med. 2023, 9, 1014340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, A.R.; Degerud, E.; Sterud, T. Onset of work-life conflict increases risk of subsequent psychological distress in the Norwegian working population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AarØ, L.E.; Knapstad, M.; Nilsen, T.; Skogen, J.C.; Nes, R.B.; Leino, T.; Riise, I.A.; Johansen, R.; GrØtvedt, L.; Vedaa, Ø. The Norwegian Counties Public Health Survey (NCPHS): A design study. Scand. J. Public Health 2024, 14034948241287853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangul, V.; Holmen, T.L.; Langhammer, A.; Ingul, J.M.; Pape, K.; Fenstad, J.S.; Kvaløy, K. Cohort Profile Update: The Young-HUNT Study, Norway. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2024, 53, dyae013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Shi, Z. Exposure, perceived risk, and psychological distress among general population during the COVID-19 lockdown in Wuhan, China. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1086155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Hannigan, L.J.; Brandlistuen, R.E.; Nesvåg, R.; Trogstad, L.; Magnus, P.; Unnarsdóttir, A.B.; Valdimarsdóttir, U.A.; Andreassen, O.A.; Ask, H. Mental Distress Among Norwegian Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Predictors in Initial Response and Subsequent Trajectories. Int. J. Public Health 2023, 68, 1606164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, I.; Henseke, G. Social inequalities in young people’s mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: Do psychosocial resource factors matter? Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 820270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, D.S.; Sarvet, A.L.; Meyers, J.L.; Saha, T.D.; Ruan, W.J.; Stohl, M.; Grant, B.F. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nübel, J.; Guhn, A.; Müllender, S.; Le, H.D.; Cohrdes, C.; Köhler, S. Persistent depressive disorder across the adult lifespan: Results from clinical and population-based surveys in Germany. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivertsen, B.; Skogen, J.C.; Reneflot, A.; Knapstad, M.; Smith, O.R.F.; Aarø, L.E.; Kirkøen, B.; Lagerstrøm, B.O.; Knudsen, A.K.S. Assessing Diagnostic Precision: Adaptations of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-5/10/25) Among Tertiary-Level Students in Norway. Clin. Psychol. Eur. 2024, 6, e13275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Üstün, T.B. The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the world health organization (WHO) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI). Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2004, 13, 93–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.; Üstün, T. The World Health Organization composite international diagnostic interview. In The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; pp. 58–90. [Google Scholar]

- Åsvold, B.O.; Langhammer, A.; Rehn, T.A.; Kjelvik, G.; Grøntvedt, T.V.; Sørgjerd, E.P.; Fenstad, J.S.; Heggland, J.; Holmen, O.; Stuifbergen, M.C.; et al. Cohort Profile Update: The HUNT Study, Norway. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 52, e80–e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edition, F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Am. Psychiatric. Assoc. 2013, 21, 591–643. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1992; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Haro, J.M.; Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, S.; Brugha, T.S.; De Girolamo, G.; Guyer, M.E.; Jin, R.; Lepine, J.P.; Mazzi, F.; Reneses, B.; Vilagut, G. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2006, 15, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevethan, R. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values: Foundations, pliabilities, and pitfalls in research and practice. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiller, W.; Zaudig, M.; Bose, M.V. The overlap between depression and anxiety on different levels of psychopathology. J. Affect. Disord. 1989, 16, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbozinek, T.D.; Rose, R.D.; Wolitzky-Taylor, K.B.; Sherbourne, C.; Sullivan, G.; Stein, M.B.; Roy-Byrne, P.P.; Craske, M.G. Diagnostic overlap of generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder in a primary care sample. Depress. Anxiety 2012, 29, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, T.C.F.; Miot, H.A. Use of ROC Curves in Clinical and Experimental Studies; SciELO: São Paulo, Brasil, 2020; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Vilagut, G.; Forero, C.G.; Barbaglia, G.; Alonso, J. Screening for depression in the general population with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D): A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, A.K.; Hotopf, M.; Skogen, J.C.; Øverland, S.; Mykletun, A. The Health Status of Nonparticipants in a Population-based Health Study: The Hordaland Health Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 172, 1306–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørstavik, R.E.; Kendler, K.S.; Czajkowski, N.; Tambs, K.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T. The relationship between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder: A population-based twin study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 1866–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, A.K.S.; Stene-Larsen, K.; Gustavson, K.; Hotopf, M.; Kessler, R.C.; Krokstad, S.; Skogen, J.C.; Øverland, S.; Reneflot, A. Prevalence of mental disorders, suicidal ideation and suicides in the general population before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway: A population-based repeated cross-sectional analysis. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2021, 4, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Information | |

|---|---|

| Women, n = (%) | 860 (64%) |

| Age, mean | 39 (SD = 12, range 20–66) |

| Higher education, (lower or higher degree of higher education) | 1036 (77%) |

| Diagnoses From CIDI, 30 Days | |

| GAD or MDD *, n = (%) | 56 (4.2%) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 36 (2.7%) |

| Major depressive disorder | 32 (2.3%) |

| Any affective or anxiety disorder ** | 172 (13%) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 154 (11.5%) |

| Any affective disorder | 36 (2.7%) |

| Item | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| Feeling fearful | 0.83 |

| Nervousness or shakiness inside | 0.83 |

| Feeling hopeless about the future | 0.77 |

| Feeling blue | 0.78 |

| Worry too much about things | 0.85 |

| CIDI Diagnoses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAD or MDD * | GAD | MDD | ||

| HSCL cut-off ≥ 1.80 | Sensitivity | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.77 |

| Specificity | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.85 | |

| PPV | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.10 | |

| NPV | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| HSCL cut-off ≥ 2.00 | Sensitivity | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.74 |

| Specificity | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.90 | |

| PPV | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.16 | |

| NPV | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| HSCL cut-off ≥ 2.25 | Sensitivity | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.38 |

| Specificity | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.96 | |

| PPV | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.20 | |

| NPV | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | |

| Current Sample | Hypothetical Population I | Hypothetical Population II | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of GAD or MDD, % (n=) | 4.2% (56) | 8.4% (113) | 16% (215) |

| Sensitivity of HSCL-5 cut-off ≥ 1.80 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| Specificity of HSCL-5 cut-off ≥ 1.80 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Positive predictive value (PPV) | 0.21 | 0.36 | 0.53 |

| Negative predictive value (NPV) | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kirkøen, B.; Ørstavik, R.E.; Reneflot, A.; Skogen, J.C.; Sivertsen, B.; Knudsen, A.K.S. The Ability of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-5 to Identify Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder in the General Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050698

Kirkøen B, Ørstavik RE, Reneflot A, Skogen JC, Sivertsen B, Knudsen AKS. The Ability of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-5 to Identify Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder in the General Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):698. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050698

Chicago/Turabian StyleKirkøen, Benedicte, Ragnhild Elise Ørstavik, Anne Reneflot, Jens Christoffer Skogen, Børge Sivertsen, and Ann Kristin Skrindo Knudsen. 2025. "The Ability of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-5 to Identify Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder in the General Population" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050698

APA StyleKirkøen, B., Ørstavik, R. E., Reneflot, A., Skogen, J. C., Sivertsen, B., & Knudsen, A. K. S. (2025). The Ability of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-5 to Identify Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder in the General Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 698. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050698