Illegal Dumping Sites in Bloemfontein, South Africa: Respiratory Symptoms, Risk Factors, and Community Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

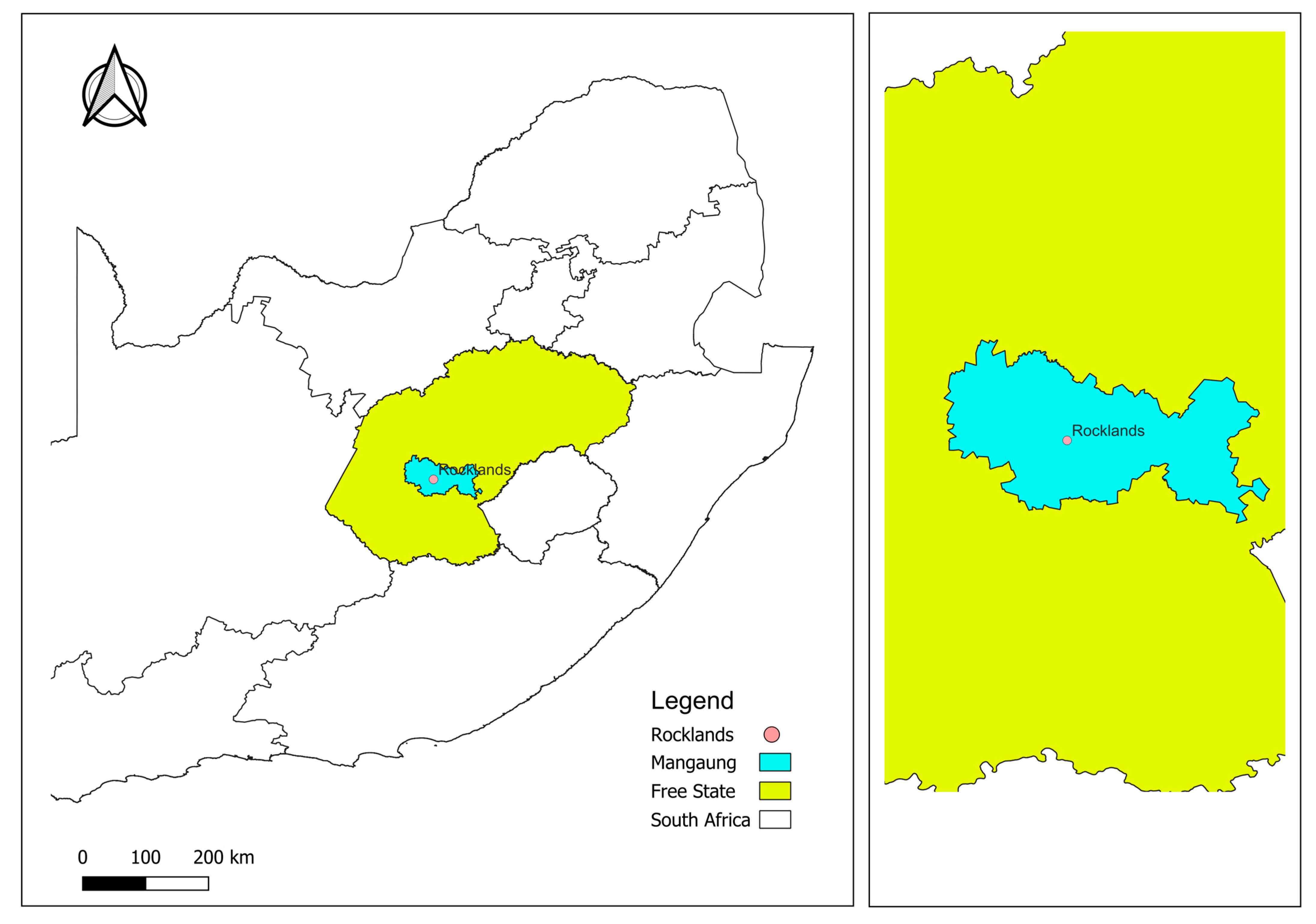

2.1. Research Design, Study Setting, and Population

2.2. Selection of Houses and Study Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.2. Prevalence of Respiratory Symptoms

3.3. Generalized Linear Model Analysis of Proximity to Illegal Dumping Sites and Respiratory Symptoms

3.4. Awareness, Perceptions, and Solutions to Illegal Domestic Waste Dumping

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Compendium of WHO and Other UN Guidance on Health and Environment. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/compendium-on-health-and-environment (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Etea, T.; Girma, E.; Mamo, K. Risk perceptions and experiences of residents living nearby municipal solid waste open dumpsite in Ginchi town, Ethiopia: A qualitative study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 2035–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syafrudin, S.; Ramadan, B.S.; Budihardjo, M.A.; Munawir, M.; Khair, H.; Rosmalina, R.T.; Ardiansyah, S.Y. Analysis of factors influencing illegal waste dumping generation using GIS spatial regression methods. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyai, O.; Nunu, W.N. Health effects associated with proximity to waste collection points in Beitbridge Municipality, Zimbabwe. Waste Manag. 2020, 105, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhubu, T.; Muzenda, E. Determination of the least impactful municipal solid waste management option in Harare, Zimbabwe. Processes 2019, 7, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziraba, A.; Orindi, B.; Muuo, S.; Floyd, S.; Birdthistle, I.J.; Mumah, J.; Osindo, J.; Njoroge, P.; Kabiru, C.W. Understanding HIV risks among adolescent girls and young women in informal settlements of Nairobi, Kenya: Lessons for DREAMS. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chireshe, A.T.; Shabani, T. Safety and health risks associated with illegal municipal solid waste disposal in urban Zimbabwe. “A case of Masvingo City”. Saf. Extrem. Environ. 2023, 5, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, B. Are Chronic Disease Indicators Associated with Living Close to Treatment, Waste, & Disposal Sites (Landfills) in Southeastern United States? Middle Tennessee State University: Murfreesboro, TN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mataloni, F.; Badaloni, C.; Golini, M.N.; Bolignano, A.; Bucci, S.; Sozzi, R.; Forastiere, F.; Davoli, M.; Ancona, C. Morbidity and mortality of people who live close to municipal waste landfills: A multisite cohort study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. An Estimated 12.6 Million Deaths Each Year Are Attributable to Unhealthy Environments. 2016. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/15-03-2016-an-estimated-12-6-million-deaths-each-year-are-attributable-to-unhealthy-environments (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Fazzo, L.; Manno, V.; Iavarone, I.; Minelli, G.; De Santis, M.; Beccaloni, E.; Scaini, F.; Miotto, E.; Airoma, D.; Comba, P. The health impact of hazardous waste landfills and illegal dumps contaminated sites: An epidemiological study at ecological level in Italian Region. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 996960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grangxabe, X.S.; Maphanga, T.; Madonsela, B.S.; Gqomfa, B.; Phungela, T.T.; Malakane, K.C.; Thamaga, K.H.; Angwenyi, D. The escalation of Informal Settlement and the high levels of illegal dumping post-apartheid: Systematic review. Challenges 2023, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngalo, N.; Thondhlana, G. Illegal Solid-Waste Dumping in a Low-Income Neighbourhood in South Africa: Prevalence and Perceptions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government, S.A. National Waste Management Strategy. 2024. Available online: https://www.dffe.gov.za/national-waste-management-strategy (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Government, S.A. National Environmental Management: Waste Act 59 of 2008. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/national-environmental-management-waste-act (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Godfrey, L.; Roman, H.; Smout, S.; Maserumule, R.; Mpofu, A.; Ryan, G.; Mokoena, K. Unlocking the Opportunities of a Circular Economy in South Africa, in Circular Economy: Recent Trends in Global Perspective; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 145–180. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, R.C.; Simões, P. Does the sunshine regulatory approach work?: Governance and regulation model of the urban waste services in Portugal. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2008, 52, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatsSA. Rocklands. 2011. Available online: https://census2011.adrianfrith.com/place/499024006 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Tomita, A.; Cuadros, D.F.; Burns, J.K.; Tanser, F.; Slotow, R. Exposure to waste sites and their impact on health: A panel and geospatial analysis of nationally representative data from South Africa, 2008–2015. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e223–e234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadhullah, W.I.; Jafri, N.F.; Jaafar, M.H.; Abdullah, H. Community respiratory symptoms survey among residents in close proximity to a landfill in a tropical rural area. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2021, 16, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kret, J.; Dame, L.D.; Tutlam, N.; DeClue, R.W.; Schmidt, S.; Donaldson, K.; Lewis, R.; Rigdon, S.E.; Davis, S.; Zelicoff, A.; et al. A respiratory health survey of a subsurface smouldering landfill. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.F.; Hod, R.; Toha, H.R.; Mohammed Nawi, A.; Idris, I.B.; Mohd Yusoff, H.; Sahani, M. The impacts of illegal toxic waste dumping on children’s health: A review and case study from Pasir Gudang, Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Chokhandre, P.; Salve, P.S.; Rajak, R. Open dumping site and health risks to proximate communities in Mumbai, India: A cross-sectional case-comparison study. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 9, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönbrodt, F.D.; Perugini, M. At what sample size do correlations stabilize? J. Res. Personal. 2013, 47, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Rahman, H.A.; Ismail, S.N.; Bin-Qiang, J. Applying participatory research in solid waste management: A systematic literature review and evaluation reporting. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyobuhungiro, R.V.; Schenck, C.J. The dynamics of indiscriminate/illegal dumping of waste in Fisantekraal, Cape Town, South Africa. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, L.K.; Kapwata, T.; Oelofse, S.; Breetzke, G.; Wright, C.Y. Waste disposal practices in low-income settlements of South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, A.; Mazzanti, M.; Nicolli, F.; Zoli, M. Illegal waste disposal: Enforcement actions and decentralized environmental policy. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2018, 64, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, V.; Castagnoli, A.; Pecorini, I.; Chiarello, F. Identifying technologies in circular economy paradigm through text mining on scientific literature. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0312709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–35 | 126 (65.0) |

| 36–49 | 51 (22.0) | |

| 50–65 | 23 (13.0) | |

| Ethnicity | Black | 200 (100) |

| Gender | Male | 104 (52.0) |

| Female | 92 (46.0) | |

| Binary | 4 (2.0) | |

| Home language | Setswana | 67 (34.0) |

| Sesotho | 78 (39.0) | |

| Xhosa | 50 (25.0) | |

| Zulu | 5 (2.0) | |

| Income group Conversion date: 7 April 2025 (Rands to USD) | $27–$270 | 84 (45.0) |

| $270–$540 | 42 (22.0) | |

| $540–$1080 | 15 (8.0) | |

| Do not want to answer | 46 (25.0) | |

| Educational level | Primary/Grade 9 | 41 (21.0) |

| Grade 12/higher certificate/ undergraduate | 159 (79.0) | |

| How long have you stayed in this area? | 1–4 years | 27 (13) |

| 5 years and more | 173 (87.0) |

| Distance | Age | Gender | Education | Income | Duration | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 0–5 km | >5 km | 18–35 Years | 36–50 | >51 | Female | Male | Primary/Gr 9 | Gr 12/Higher Certificate/ Undergraduate | ≤R10,000 | >R10,000 | 1–4 Years | 5 and More |

| Wheezing or whistling in the chest | 23 (20.0) | 6 (7.0) * | 13 (10) | 8 (18) | 8 (31) * | 15 (15) | 14 (15) | 5 (12) | 24 (15) | 13 (10) | 14 (23) * | 2 (7) | 27 (16) |

| Chest tightness | 23 (20.0) | 6 (7.0) * | 15 (12) | 9 (21) | 5 (19) | 18 (18) | 11 (12) | 5 (13) | 24 (16) | 13 (10) | 13 (22) * | 3 (11) | 26 (15) |

| Shortness of breath | 24 (23) | 14 (18) | 11 (9) | 12 (31) | 15 (58) * | 20 (22) | 17 (20) | 14 (35) | 24 (17) * | 26 (22) | 11 (21) | 2 (8) | 36 (23) |

| Coughing | 48 (43) | 22 (27) * | 35 (28) | 20 (48) | 15 (58) * | 36 (36) | 33 (38) | 15 (39) | 55 (36) | 38 (31) | 30 (52) * | 8 (32) | 62 (37) |

| Variable | M1 * | M2 * | M3 * |

|---|---|---|---|

| PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | |

| Wheezing or whistling in the chest | |||

| Proximity to open illegal dumping sites | |||

| >5 km (ref.) | |||

| <5 km | 2.78 (1.56–6.39) ** | 2.56 (1.05–6.24) ** | 2.77 (1.10–6.98) ** |

| Chest tightness | |||

| Proximity to open illegal dumping sites | |||

| >5 km (ref.) | |||

| <5 km | 2.78 (1.18–6.54) ** | 2.73 (1.15–6.52) ** | 2.86 (1.19–6.84) ** |

| Shortness of breath | |||

| Proximity to open illegal dumping sites | |||

| >5 km (ref.) | |||

| <5 km | 1.25 (0.70–2.27) | 0.80 (0.46–1.38) | 0.81 (0.46–1.43) |

| Coughing | |||

| Proximity to open illegal dumping sites | |||

| >5 km (ref.) | |||

| <5 km | 1.59 (1.05–2.41) | 1.46 (0.93–2.26) | 1.45 (0.92–2.27) |

| Outcome | Sociodemographic Characteristics | PR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Wheezing | Female | 1.37 (−0.08–2.81) |

| Male | 0.73 (−0.73–2.19) | |

| 36–50 | 2.05 (0.53–3.56) * | |

| >51 | 0.07 (−0.88–1.02) | |

| Primary/Gr 9 | 17.89 (16.97–18.81) * | |

| Gr 12/higher certificate/undergraduate | 0.84 (−0.14–1.80) | |

| Chest tightness | Female | 0.80 (−0.26–1.86) |

| Male | 1.58 (0.12–3.03) | |

| 36–50 | 0.99 (−0.70–2.07) | |

| >51 | 0.92 (−0.47–2.32) | |

| Primary/Gr 9 | 16 (15.43–17.86) * | |

| Gr 12/higher certificate/undergraduate | 0.85 (−0.05–1.75) | |

| Shortness of breath | Female | −0.27 (−0.96–0.42) |

| Male | −0.03 (−1.25–1.20) | |

| 36–50 | 0.35 (−0.99–1.70) | |

| >51 | −0.49 (−1.08–0.09) | |

| Primary/Gr 9 | −0.38 (−1.15–0.39) | |

| Gr 12/higher certificate/undergraduate | 0.56 (−0.88–0.92) | |

| Coughing | Female | 0.28 (−0.32–0.88) |

| Male | 0.48 (−0.27–1.28) | |

| 36–50 | 0.54 (−0.08–1.16) | |

| >51 | 0.15 (−0.44–0.74) | |

| Primary/Gr 9 | −0.49 (−1.50–0.51) | |

| Gr 12/higher certificate/undergraduate | 0.47 (−0.02–0.98) |

| Characteristics | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Do you think illegal dumping of domestic waste is a problem in your community? | No | 17 (8.5) |

| Yes | 177 (88.5) | |

| Do not know | 4 (2.0) | |

| Missing | 2 (1.0) | |

| Are you aware of the negative health effects of illegal domestic waste dumping? | No | 93 (48.0) |

| Yes | 76 (38.0) | |

| Do not know | 26 (13.0) | |

| Missing | 5 (1.0) | |

| How often do you notice people dumping waste in your area? | I hardly see items being dumped | 29 (14.5) |

| Everyday | 117 (58.5) | |

| Once a week | 47 (23.5) | |

| I do not know | 7 (3.5) | |

| Which age group usually dumps domestic waste in this area? | Children of 2–9 years only | 4 (2.0) |

| Teenagers of 10–19 years only | 35 (18.0) | |

| Children (2–9 years) and teenagers (10–19 years) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Adults of 20–54 years only | 120 (62.0) | |

| Elderly of 55 years and above | 13 (7.0) | |

| Teenagers and adults | 24 (12.0) | |

| Children and adults | 1 (1.0) | |

| Missing | 2 (1.0) | |

| Have you or any family member ever left any item from your household in open spaces? | No | 138 (69.0) |

| Yes | 40 (20.0) | |

| Missing | 22 (11) | |

| Has illegal domestic dumping been a problem in this community in previous years? | No | 27 (13.5) |

| Yes | 159 (79.5) | |

| Do not know | 13 (6.5) | |

| Missing | 1(0.5) | |

| What are the causes of illegal domestic waste dumping in your community? | Multiple open spaces | 57 (28.5) |

| Affordable | 1 (0.5) | |

| Lack of knowledge regarding proper disposal of waste | 14 (7.0) | |

| Lack of municipal services | 80(40.0) | |

| Multiple open spaces and lack of municipal services | 43 (21.5) | |

| Multiple open spaces and lack of knowledge regarding disposal of waste | 4 (2.0) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | |

| What are the measures which can be implemented by the community to reduce the issues of illegal domestic waste dumping? | Stop dumping waste | 20 (10.0) |

| Report a person dumping | 18 (9.0) | |

| Keep the community clean | 51 (25.5) | |

| Recycling | 64 (32.0) | |

| All of the above | 45 (22.5) | |

| Missing | 2 (1.0) | |

| Can awareness campaigns which are related to proper waste disposal and education on the effects of illegal waste dumping be of value? | No | 8 (4.0) |

| Yes | 181 (90.5) | |

| Do not know | 10 (5.0) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | |

| If there are different bins for each type of waste allocated to your household, would you be willing to sort it out and dispose of waste correctly? | No | 3 (1.5) |

| Yes | 188 (94.0%) | |

| Do not know | 8 (4.0%) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maluleka, B.; Rathebe, P.C.; Shezi, B. Illegal Dumping Sites in Bloemfontein, South Africa: Respiratory Symptoms, Risk Factors, and Community Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050685

Maluleka B, Rathebe PC, Shezi B. Illegal Dumping Sites in Bloemfontein, South Africa: Respiratory Symptoms, Risk Factors, and Community Perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050685

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaluleka, Botle, Phoka C. Rathebe, and Busisiwe Shezi. 2025. "Illegal Dumping Sites in Bloemfontein, South Africa: Respiratory Symptoms, Risk Factors, and Community Perspectives" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050685

APA StyleMaluleka, B., Rathebe, P. C., & Shezi, B. (2025). Illegal Dumping Sites in Bloemfontein, South Africa: Respiratory Symptoms, Risk Factors, and Community Perspectives. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050685