Lessons Learned in Transgender Peer Navigation: A Year of Reflective Journaling

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Background

1.2. Our Project’s Work

1.3. Reflective Journalling and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Analysis

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

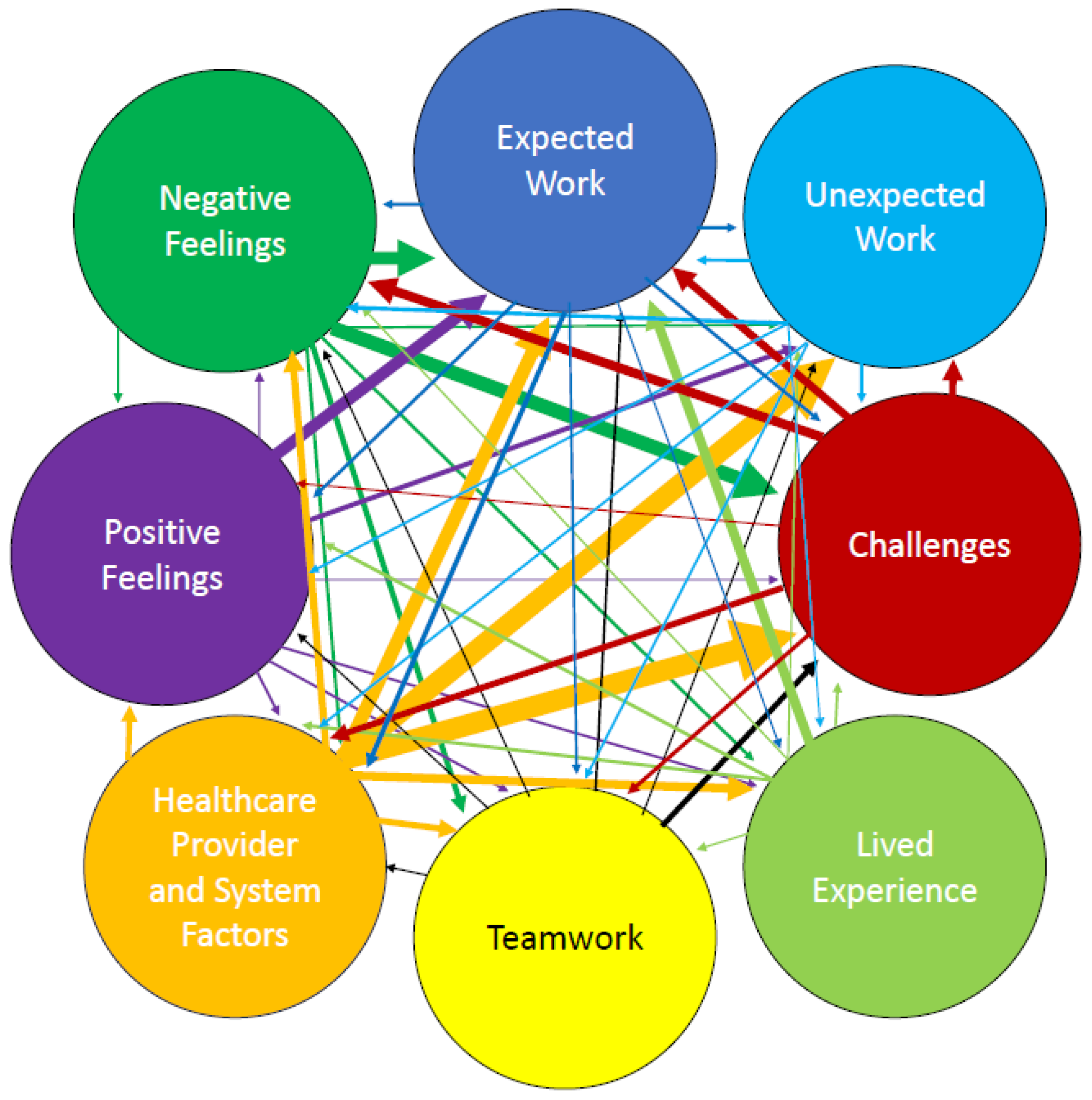

3.1. Themes

3.1.1. Expected Work

3.1.2. Unexpected Work

“Right now, our demand is so high and it’s really hard to keep up and assist everyone. This wouldn’t be an issue if it weren’t for the barriers in our systems. For example, I have clients needing mental health counsellors and family doctors in the city and rural areas. But there just isn’t anywhere I can send them right now!”

3.1.3. Teamwork

“We’re really fortunate to have help and [support] from these nice folks. It’s admirable to see how successful their program is. They have so much organization in their services, and everything is so efficient and streamlined. Although we’re starting from ground zero in Saskatchewan, it’s nice to have something to aim towards as we build our program. The team at Trans Care BC is very inspiring!”

“We spoke with someone [who] is working with a team of law students to conduct a name change clinic and provide financial support for people [who] need financial support. This is going to be great because even for myself that the cost of doing a name change is steep for a piece of paper and a card. But this will be great because we can do this for people and there won’t be any mistakes because we will all know what is required to change markers.”

3.1.4. Lived Experience

“Representation in working with the trans community is essential. It is always nerve wracking to seek support as a trans person because we often do not see trans people doing this work. We need people with lived experience to do these services because trust and translation are so important. If my clients didn’t trust me, I wouldn’t have achieved as much with each client. Translation is important because the health system is so complicated for community members; most people wouldn’t know about self-referrals if this service didn’t exist.”

“I found it quite interesting how quickly [a client] felt comfortable and safe with me. Within a few minutes into our call, they were opening up to me about their experiences with gender and revealing pieces of them that they reported not having told other people.”

“The majority of our presentation covered case studies. Many of the cases related to personal experiences that [we] have had, which we know many of our community members have faced as well (Navigator B).”

3.1.5. Healthcare Provider and Systemic Factors

“When I call clinics or reach out to professionals, I am not seen as important or credible. I am brushed off as if I’m just a nosy trans activist trying to do community advocacy. I wish my position was regarded more as healthcare role.”

“One thing that came up a few times this week was people needing voice therapy. We have two options in [city] and even if folks do voice therapy online, it is not covered and many of them can’t pay the fees.”

3.1.6. Challenges

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TGD | Transgender or gender-diverse |

| HPC | Healthcare provider |

| CBO | Community-based organisation |

| 2SLGBTQ+ | Two Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, plus other identities |

References

- Scheim, A.I.; Coleman, T.; Lachowsky, N.; Bauer, G.R. Health care access among transgender and nonbinary people in Canada, 2019: A cross-sectional survey. CMAJ Open 2021, 9, E1213–E1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopherson, L.; McLaren, K.; Schramm, L.; Holinaty, C.; Ruddy, G.; Boughner, E.; Clay, A.; McCarron, M.; Clark, M. Assessment of knowledge, comfort, and skills working with transgender clients of Saskatchewan family physicians, family medicine residents, and nurse practitioners. Transgender Health 2022, 7, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, A.E.; Doucet, S.; Luke, A. Exploring the role of lay and professional patient navigators in Canada. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2020, 25, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trans Care BC. Available online: https://www.transcarebc.ca/how-to-get-care/peer-support (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Phillips, S.; Nonzee, N.; Tom, L.; Murphy, K.; Hajjar, N.; Bularzik, C.; Dong, X.; Simon, M.A. Patient navigators’ reflections on the navigator-patient relationship. J. Cancer Educ. 2014, 29, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, A.P.; Bourgoin, N.; Ndihokubwayo, N.; Lemonde, M.; Toal-Sullivan, D.; Timony, P.E.; Warnet, C.; Chomienne, M.H.; Kendall, C.E.; Premji, K.; et al. Learning from reflective journaling: The experience of navigators in assisting patients access to health and social resources in the community. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2022, 60, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Llorente, T.M.; Navarro-Martinez, O.; Ibanez-del Valle, V.; Perez-Bermejo, M. Using the reflective journal to improve practical skills integrating affective and self-critical aspects in impoverished international environments: A pilot test. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, G.; McCarron, M.; Reid, M.; Fayant-McLeod, T.; Gulka, E.; Young, J.; Clark, M.; Madill, S.J. Using focus groups to inform a peer health navigator service for people who are transgender and gender diverse in Saskatchewan, Canada. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e14022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulka, E.; Rose, G.; McCarron, M.; Reid, M.; Madill, S.J.; Clark, M. Interviews with clients and healthcare providers to assess a pilot healthcare navigator service for people who are transgender and gender diverse in Saskatchewan, Canada. Ann. Fam. Med. 2025, 23, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulka, E.; Reid, M.; Rose, G.; Madill, S.J.; Clark, M. Client surveys and usage statistics for transgender peer health navigator pilot in Saskatchewan, Canada. Correspondence S. Madill, School of Rehabilitation Science, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. 2025; to be submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Chatfield, S.L. Strategies to Enhance and Emphasize the Value of Your Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) Research. Available online: https://www.apa.org/career-development/interpretative-phenomenological-analysis-faq.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- Engward, H.; Goldspink, S. Lodgers in the house: Living with the data in interpretive phenomenological analysis research. Reflective Pract. 2020, 21, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, M.; Smith, J.A. The fearfulness of chronic pain and the centrality of the therapeutic relationship in containing it: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2008, 5, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saskatchewan Trans Health Coalition: Saskatchewan Medical Transition Guide. Available online: https://www.transsask.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Saskatchewan-Medical-Transition-Guide-Final-Draft-1.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Kelly, E.; Fulginiti, A.; Pahwa, R.; Tallen, L.; Duan, L.; Brekke, J.S. A pilot test of a peer navigator intervention for improving the health of individuals with serious mental illness. Community Ment. Health J. 2013, 50, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belanger, A.; Lim, M.; Cheyne, A.; Eickmeier, T.; Sexton, B.; Neufeld, A.; Nemisz, J.; Alexander-Arias, C.; Omer, F.; Rambajue, S. Family engagement in action: An evaluation of a peer navigation team in community-based paediatric rehabilitation. Int. J. Integr. Care 2023, 23, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Walleghem, N.; MacDonald, C.A.; Dean, H.J. The maestro project: A patient navigator for the transition of care for youth with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2011, 24, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancouver-Fraser CMHA: Peer Navigator Program. Available online: https://cmhavf.ca/programs/peer-navigator-3/. (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Thorne, S. Interpretive Description: Qualitative Research for Applied Practice, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Themes | Tasks |

|---|---|

| 1. Expected work— work that was anticipated by the research team when planning the intervention | Assisting with access to hormone therapy, including blockers |

| Addressing misinformation | |

| Education—provided by navigators, and navigators’ education needs | |

| Creating resources | |

| Connecting MDs to mentors | |

| Facilitating systemic change and increased capacity | |

| Peer support | |

| Networking with CBOs | |

| Managing clients’ expectations | |

| Ensuring clients’ safety in interactions with navigators | |

| Suicide prevention | |

| 2. Unexpected work—work that emerged as important during the intervention | High volume of email/contacts |

| Effects of COVID-19 on work | |

| Education—the volume of education provided and the variety of audiences were unexpected. | |

| Education—received | |

| Legal clinics—name and gender marker | |

| Difficulty finding affirming HCPs | |

| Finding funding for clients/free clinics for services not covered by provincial health insurance: e.g., laser hair removal and many mental healthcare services | |

| Receiving donations of gender affirming products: e.g., binders and gaffs | |

| Social media/communication: it was not anticipated that it would be the most effective way to communicate with HCPs | |

| 3. Teamwork—the high degree to which the navigators’ work depended upon working collaboratively with each other and in partnership with local, regional, and other trans-focused CBOs | Communication between the navigators |

| Expectations for attending training/meetings at hosting CBO | |

| Mentorship from other navigators from outside of SK | |

| Creating legal change clinic | |

| CBOs have very limited capacity to financially support people | |

| Networking in health system | |

| CBOs provide safe mental health services | |

| Hormone injections provided by sexual health CBO | |

| Defining roles with other CBOs to avoid duplicating services | |

| Publicity and referrals from CBOs | |

| Lack of support when CBO is reorganizing | |

| Education sessions with non-2SLGBTQ+ CBOs | |

| 4. Lived experience—the importance of being trans themselves for working effectively as navigators | Role change from trans person to navigator |

| Questioning how own experience affects expectations for clients | |

| Pre-existing understanding of community needs and available services | |

| Lived experience is preparation for navigator job | |

| Positive reactions from clients and parents | |

| Trusted because of lived experience | |

| High expectations of self and from others | |

| Small province and trans community; therefore, must share support spaces with clients | |

| Rural and older clients appreciate connection to other trans people | |

| 5. Challenges—factors that made the jobs more complicated and demanded more emotional energy | Lack of funding: e.g., mental healthcare, aesthetic services |

| Helping people access hormone therapy, including hormone blockers | |

| Lack of HCPs, both those able to provide trans-specific care and generally | |

| COVID-19 restrictions | |

| Addressing misinformation | |

| Communicating with HCPs | |

| Education sessions that go poorly: e.g., transphobic reactions, HCPs attached to outdated standards of trans care | |

| Lack of trans-affirming mental healthcare providers | |

| High expectations from clients | |

| Lack of support from hosting CBOs | |

| Lack of support and resources for TGD youth | |

| Clients’ prior negative experiences with 2SLBGTQ+ CBOs made them less willing to work with navigators | |

| Clients not knowing/not being able to articulate what they needed/wanted and refusing/being dissatisfied with what the navigators were able to offer | |

| Intersectionality of multiple marginalized identities | |

| Clients reporting that MDs were dismissive and transphobic | |

| Backlash from being a public-facing trans person | |

| 6. Healthcare provider (HCP) and systemic factors —Environmental factors that shaped the navigators’ work. | Unequal funding and lack of services in the public healthcare system |

| Navigators facilitated HCPs work: e.g., by explaining things to clients, by explaining referral processes to both clients and HCPs | |

| Variability in providers’ ability to support youth on their gender journey | |

| Lack of family MDs to provide hormone therapy and safe care | |

| Lack of affirming mental healthcare providers | |

| Lack of perceived legitimacy of navigators by HCPs | |

| Waitlists to see affirming HCPs | |

| Many HCPs need education on TGD healthcare | |

| Rushed healthcare appointments | |

| Navigator job insecurity | |

| Unequal distribution of services (HCPs and CBOs) across the province | |

| Need for increased community supports, e.g., services for youth, funding for uninsured services, gender affirming products, services for people with multiple stigmatized identities |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rose, G.; Mullock, K.; Gatin, E.; Fayant-McLeod, T.; McCarron, M.C.E.; Clark, M.; Madill, S.J. Lessons Learned in Transgender Peer Navigation: A Year of Reflective Journaling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050678

Rose G, Mullock K, Gatin E, Fayant-McLeod T, McCarron MCE, Clark M, Madill SJ. Lessons Learned in Transgender Peer Navigation: A Year of Reflective Journaling. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(5):678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050678

Chicago/Turabian StyleRose, Gwen, Ken Mullock, Elijah Gatin, T. Fayant-McLeod, Michelle C. E. McCarron, Megan Clark, and Stéphanie J. Madill. 2025. "Lessons Learned in Transgender Peer Navigation: A Year of Reflective Journaling" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 5: 678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050678

APA StyleRose, G., Mullock, K., Gatin, E., Fayant-McLeod, T., McCarron, M. C. E., Clark, M., & Madill, S. J. (2025). Lessons Learned in Transgender Peer Navigation: A Year of Reflective Journaling. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(5), 678. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22050678