Variations in Sleep, Fatigue, and Difficulty with Concentration Among Emergency Medical Services Clinicians During Shifts of Different Durations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

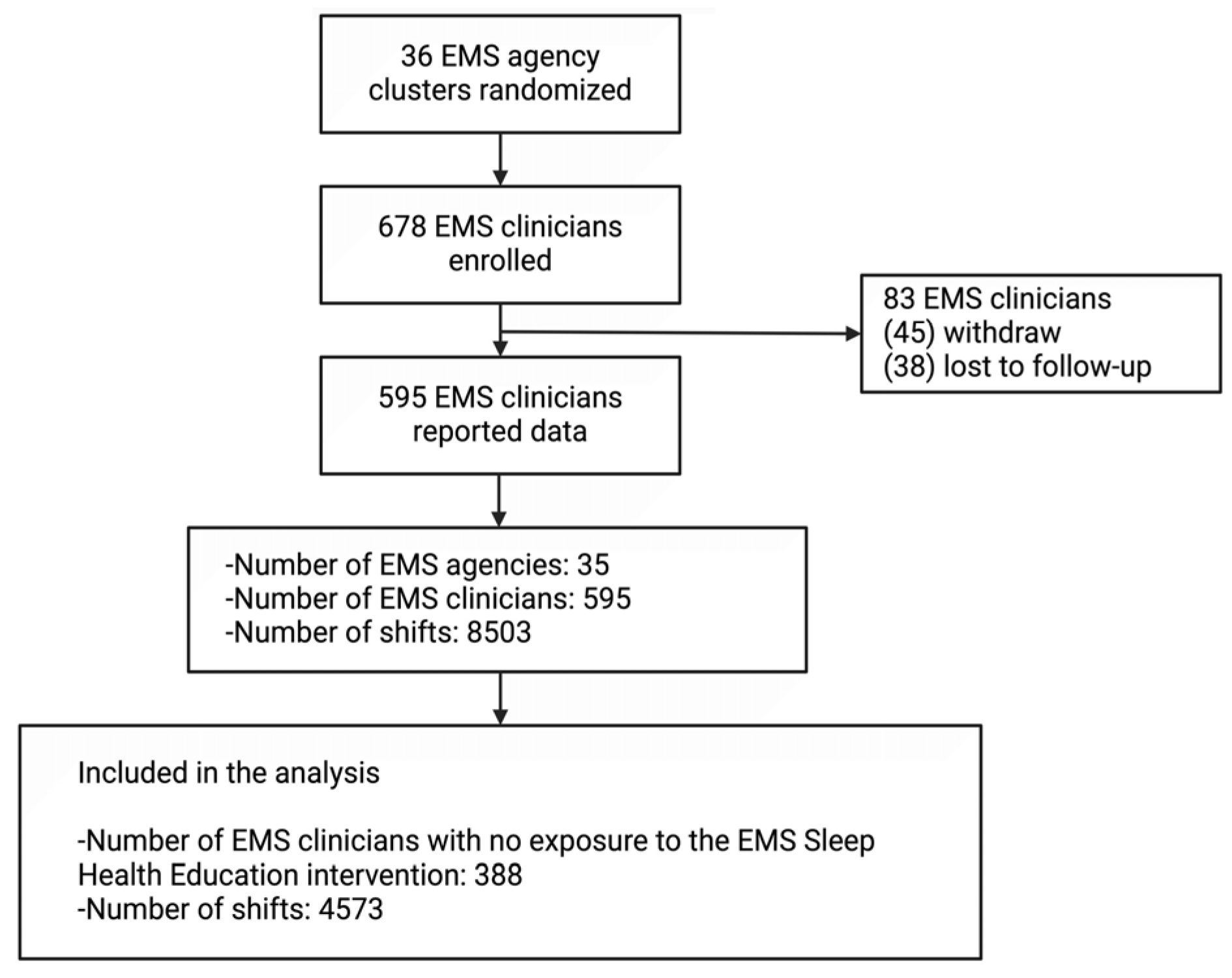

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Independent Measures of Interest

2.5. Power Calculation and Sample Size Estimation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Data

3.2. Shifts Analyzed

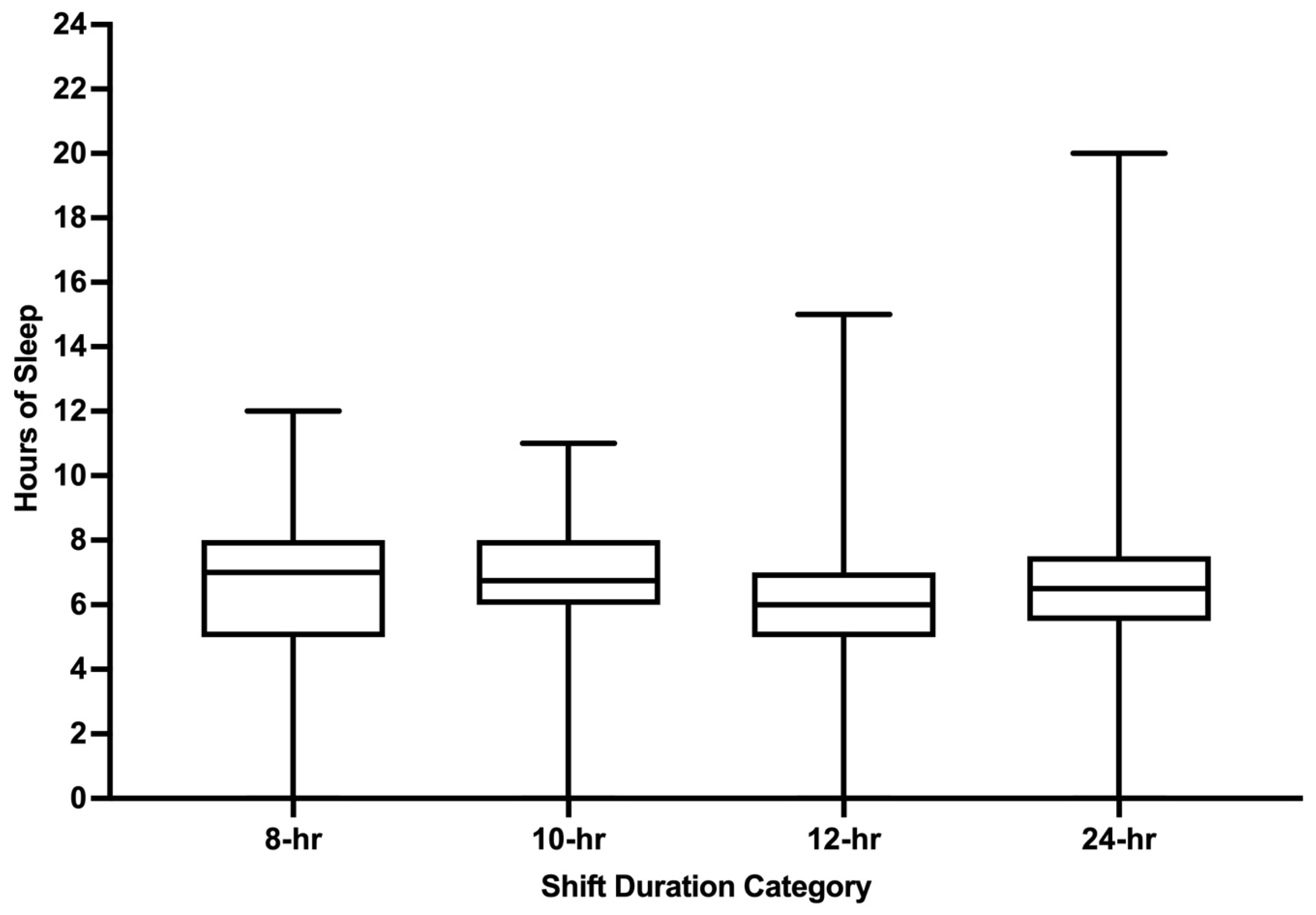

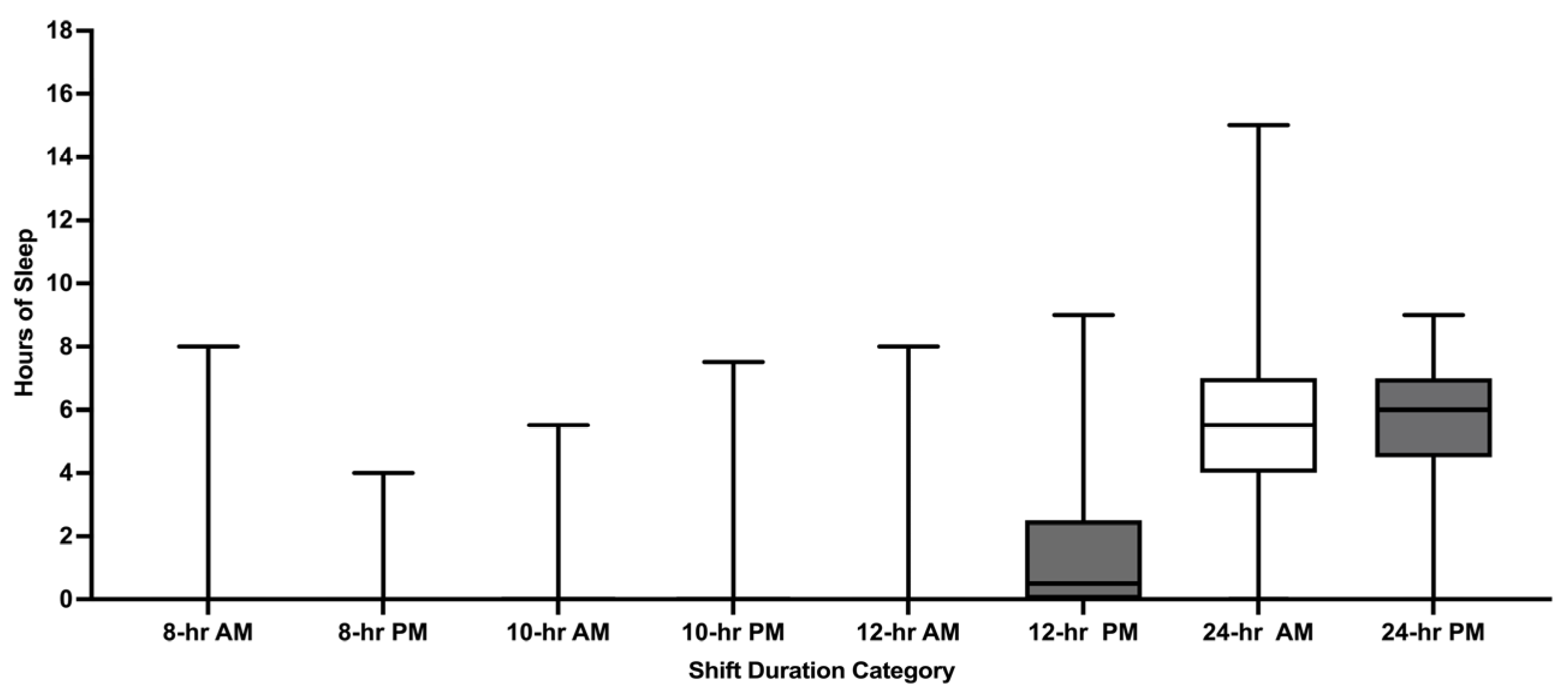

3.3. Pre-Shift Hours of Sleep

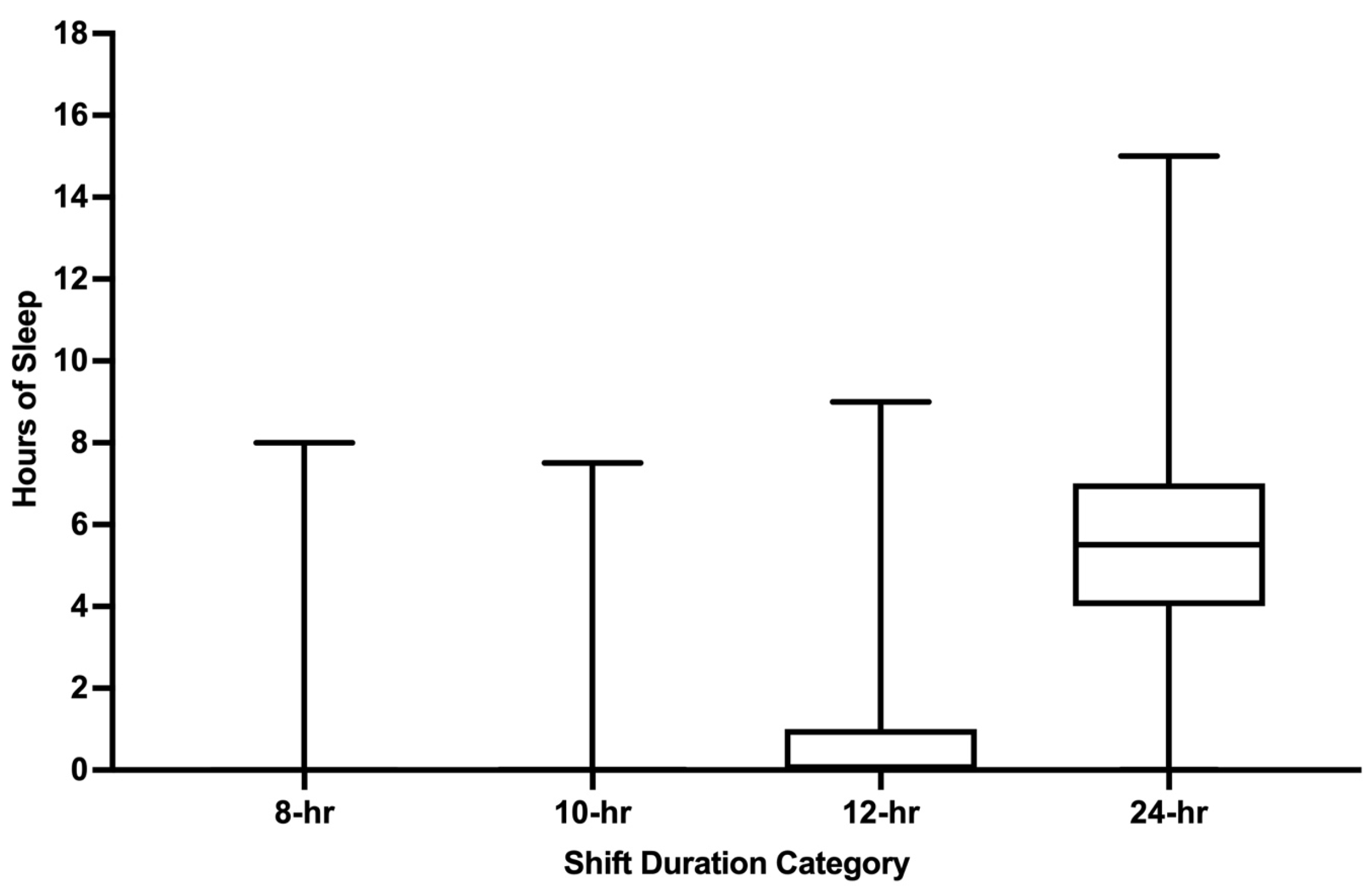

3.4. Hours of Sleep Obtained During Shift Work

3.5. Fatigue During Shifts

3.6. Sleepiness During Shifts

3.7. Difficulty with Concentration During Shifts

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EMS | Emergency Medical Services |

| U.S. | United States |

| EMA | Ecological Momentary Assessment |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| AM | Ante Meridiem |

| PM | Post Meridiem |

| NC | North Carolina |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- Patterson, P.D.; Higgins, J.S.; Van Dongen, H.P.A.; Buysse, D.J.; Thackery, R.W.; Kupas, D.F.; Becker, D.S.; Dean, B.E.; LIndbeck, G.H.; Guyette, F.X.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines for fatigue risk management in Emergency Medical Services. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2018, 22 (Suppl. S1), 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, P.D.; Martin, S.E.; Brassil, B.N.; Hsiao, W.-H.; Weaver, M.D.; Okerman, T.S.; Seitz, S.N.; Patterson, C.G.; Robinson, K. The Emergency Medical Services sleep health study: A cluster-randomized trial. Sleep Health 2023, 9, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, P.D.; Weaver, M.D.; Frank, R.C.; Warner, C.W.; Martin-Gill, C.; Guyette, F.X.; Fairbanks, R.J.; Hubble, M.W.; Songer, T.J.; Callaway, C.W.; et al. Association between poor sleep, fatigue, and safety outcomes in emergency medical services providers. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2012, 16, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rose, C.; Ter Avest, E.; Lyon, R.M. Fatigue risk assessment of a Helicopter Emergency Medical Service crew working a 24/7 shift pattern: Results of a prospective service evaluation. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2023, 31, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.D.; Suffoletto, B.P.; Kupas, D.F.; Weaver, M.D.; Hostler, D. Sleep quality and fatigue among prehospital providers. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2010, 14, 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, P.D.; Buysse, D.J.; Weaver, M.D.; Callaway, C.W.; Yealy, D.M. Recovery between Work Shifts among Emergency Medical Services Clinicians. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2015, 19, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, A.A.; Shiffman, S.; Atienza, A.A. Historical rootes and rationale of ecological momentary assessment (EMA). In The Science of Real-Time Data Capture: Self-Reports in Health Research; Stone, A.A., Shiffman, S., Atienza, A.A., Nebeling, L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman, S.; Stone, A.A.; Hufford, M.R. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.D.; Buysse, D.J.; Weaver, M.D.; Doman, J.M.; Moore, C.G.; Suffoletto, B.P.; McManigle, K.L.; Callaway, C.W.; Yealy, D.M. Real-time fatigue reduction in emergency care clinicians: The SleepTrackTXT randomized trial. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2015, 58, 1098–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.D.; Moore, C.G.; Guyette, F.X.; Doman, J.M.; Weaver, M.D.; Sequeira, D.J.; Werman, H.A.; Swanson, D.; Hostler, D.; Lynch, J.; et al. Real-Time Fatigue Mitigation with Air-Medical Personnel: The SleepTrackTXT2 Randomized Trial. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2019, 23, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.D.; Moore, C.G.; Weaver, M.D.; Buysse, D.J.; Suffoletto, B.P.; Callaway, C.W.; Yealy, D.M. Mobile phone text messaging intervention to improve alertness and reduce sleepiness and fatigue during shiftwork among emergency medicine clinicians: Study protocol for the SleepTrackTXT pilot randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014, 15, 244. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, P.D.; Moore, C.G.; Guyette, F.X.; Doman, J.M.; Sequeira, D.J.; Werman, H.A.; Swanson, D.; Hostler, D.; Lynch, J.; Russo, L.; et al. Fatigue mitigation with SleepTrackTXT2 in air medical emergency care systems: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, D.J.; Thompson, W.; Scott, J.; Franzen, P.L.; Germain, A.; Hall, M.; Moul, D.E.; Nofzinger, E.A.; Kupfer, D.J. Daytime symptoms in primary insomnia: A prospective analysis using ecological momentary assessment. Sleep Med. 2007, 8, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.J.; Proctor, S.E.; Boudreault, M.A.; Turczyn, K.M. Healthy People 2010 Criteria for Data Suppression; Healthy People 2010 Statistical Notes; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2002; pp. 1–12.

- Trotti, L.M. Waking up is the hardest thing I do all day: Sleep inertia and sleep drunkenness. Sleep Med. Rev. 2017, 35, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilditch, C.J.; McHill, A.W. Sleep inertia: Current insights. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2019, 11, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollicone, D.J.; Van Dongen, H.P.; Rogers, N.L.; Banks, S.; Dinges, D.F. Time of day effects on neurobehavioral performance during chronic sleep restriction. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2010, 81, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gill, C.; Barger, L.K.; Moore, C.G.; Higgins, J.S.; Teasley, E.M.; Weiss, P.M.; Condle, J.P.; Flickinger, K.L.; Coppler, P.J.; Sequeira, D.J.; et al. Effects of Napping During Shift Work on Sleepiness and Performance in Emergency Medical Services Personnel and Similar Shift Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2018, 22 (Suppl. S1), 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J. Sleep health: Can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep 2014, 37, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, N.F.; Badr, M.S.; Belenky, G.; Bliwise, D.L.; Buxton, O.M.; Buysse, D.; Dinges, D.F.; Gangwisch, J.; Grandner, M.A.; Kushida, C.; et al. Joint Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the Recommended Amount of Sleep for a Healthy Adult: Methodology and Discussion. Sleep 2015, 38, 1161–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshkowitz, M.; Whiton, K.; Albert, S.M.; Alessi, C.; Bruni, O.; DonCarlos, L.; Hazen, N.; Herman, J.; Adams Hillard, P.J.; Katz, E.S.; et al. National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: Final report. Sleep Health 2015, 1, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Rossheim, M.E.; Nandy, R.R. Trends in prevalence of short sleep duration and trouble sleeping among US adults, 2005–2018. Sleep 2023, 46, zsac231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, C.M.; Frochen, S.E.; Walsemann, K.M.; Ailshire, J.A. Are U.S. adults reporting less sleep?: Findings from sleep duration trends in the National Health Interview Survey, 2004–2017. Sleep 2019, 42, zsy221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannai, A.; Tamakoshi, A. The association between long working hours and health: A systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2014, 40, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.D.; Runyon, M.S.; Higgins, J.S.; Weaver, M.D.; Teasley, E.M.; Kroemer, A.J.; Matthews, M.E.; Curtis, B.R.; Flickinger, K.L.; Xun, X.; et al. Shorter Versus Longer Shift Durations to Mitigate Fatigue and Fatigue-Related Risks in Emergency Medical Services Personnel and Related Shift Workers: A Systematic Review. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2018, 22 (Suppl. S1), 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.P.; Biswas, R.K.; Ahmadi, M.; Cistulli, P.A.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Bian, W.; St-Onge, M.P.; Stamatakis, E. Sleep regularity and major adverse cardiovascular events: A device-based prospective study in 72 269 UK adults. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2024, 79, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.; Lechat, B.; Guyett, A.; Reynolds, A.C.; Lovato, N.; Naik, G.; Appleton, S.; Adams, R.; Escourrou, P.; Catcheside, P.; et al. Sleep Irregularity Is Associated With Hypertension: Findings From Over 2 Million Nights with a Large Global Population Sample. Hypertension 2023, 80, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, S.E.; Eskin, E.; Flower, D.J.; George, E.C.; Gerson, B.; Hartenbaum, N.; Hursh, S.R.; Moore-Ede, M. Fatigue risk management in the workplace. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 54, 231–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, N.; Basner, M.; Rao, H.; Dinges, D.F. Circadian rhythms, sleep deprivation, and human performance. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2013, 119, 155–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doran, S.M.; Van Dongen, H.P.; Dinges, D.F. Sustained attention performance during sleep deprivation: Evidence of state instability. Arch. Ital. Biol. 2001, 139, 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Wehrens, S.M.; Hampton, S.M.; Kerkhofs, M.; Skene, D.J. Mood, alertness, and performance in response to sleep deprivation and recovery sleep in experienced shiftworkers versus non-shiftworkers. Chronobiol. Int. 2012, 29, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joenks, L. Springdale firefighters adopt 48-hour shift schedule. In Northwest Arkansas Democrat Gazette; Northwest Arkansas Newspapers LLC: Fayetteville, AR, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Haldiman, J. Cole County Ambulance Service experimenting with 48-hour work schedule. In The Jefferson City News Tribune; News Tribune Publishing: Jefferson City, MO, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C. Jonesville Police consider 48-hour shifts, following a model tried elsewhere. In Hillsdale Daily News; Orestes Baez: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, L.S.; Bayless, K. Long hours. Low pay. Force overtime. Is Beaufort Co. EMS ‘struggling to tread water’? In The Island Packet; McClatchy Media Network: Beaufort, SC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2020 National Emergency Medical Services Assessment. Available online: https://nasemso.org/wp-content/uploads/2020-National-EMS-Assessment_Reduced-File-Size.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Fahy, R.; Evarts, B. Stein GP: US Fire Department Profile 2020; National Fire Protection Association: Quincy, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, M.J.; Sigman, M.; Golombek, D.A. Effects of lockdown on human sleep and chronotype during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R930–R931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, M.; Reinhart, M.; Dusetzina, S.B.; Walsh, C.; Griffith, K.N. Trends in U.S. self-reported health and self-care behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Shift Duration | Number (%) of Shifts Analyzed with Text Message Data N = 4573 | Percentage of Shifts with AM Start Times (Between 00:00–11:59) | Number of Individuals Documenting Shifts N = 388 | Number of Agencies (Clusters) Contributing to Shifts Analyzed N = 35 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 h | 252 (5.5%) | 81.0% | 59 | 28 |

| 10 h | 239 (5.2%) | 35.6% | 39 | 19 |

| 12 h | 1253 (27.4%) | 67.8% | 149 | 33 |

| 16 h | 72 (1.6%) | 65.3% | 35 | 22 |

| 24 h | 2657 (58.1%) | 87.2% | 286 | 29 |

| 36 h | 26 (0.6%) | 76.9% | 23 | 17 |

| 48 h | 67 (1.5%) | 86.6% | 31 | 14 |

| 60 h | 3 (0.07%) | 66.7% | 3 | 2 |

| 72 h | 4 (0.09%) | 75.0% | 3 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patterson, P.D.; Martin, S.E.; MacAllister, S.A.; Weaver, M.D.; Patterson, C.G. Variations in Sleep, Fatigue, and Difficulty with Concentration Among Emergency Medical Services Clinicians During Shifts of Different Durations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040573

Patterson PD, Martin SE, MacAllister SA, Weaver MD, Patterson CG. Variations in Sleep, Fatigue, and Difficulty with Concentration Among Emergency Medical Services Clinicians During Shifts of Different Durations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(4):573. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040573

Chicago/Turabian StylePatterson, Paul D., Sarah E. Martin, Sean A. MacAllister, Matthew D. Weaver, and Charity G. Patterson. 2025. "Variations in Sleep, Fatigue, and Difficulty with Concentration Among Emergency Medical Services Clinicians During Shifts of Different Durations" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 4: 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040573

APA StylePatterson, P. D., Martin, S. E., MacAllister, S. A., Weaver, M. D., & Patterson, C. G. (2025). Variations in Sleep, Fatigue, and Difficulty with Concentration Among Emergency Medical Services Clinicians During Shifts of Different Durations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(4), 573. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22040573