Barriers and Facilitators Concerning Involuntary Oral Care for Individuals with Dementia: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Sample Size, Setting, and Participants

2.2. Recruitment Procedure

2.3. Participant Information and Informed Consent

2.4. Data Analysis

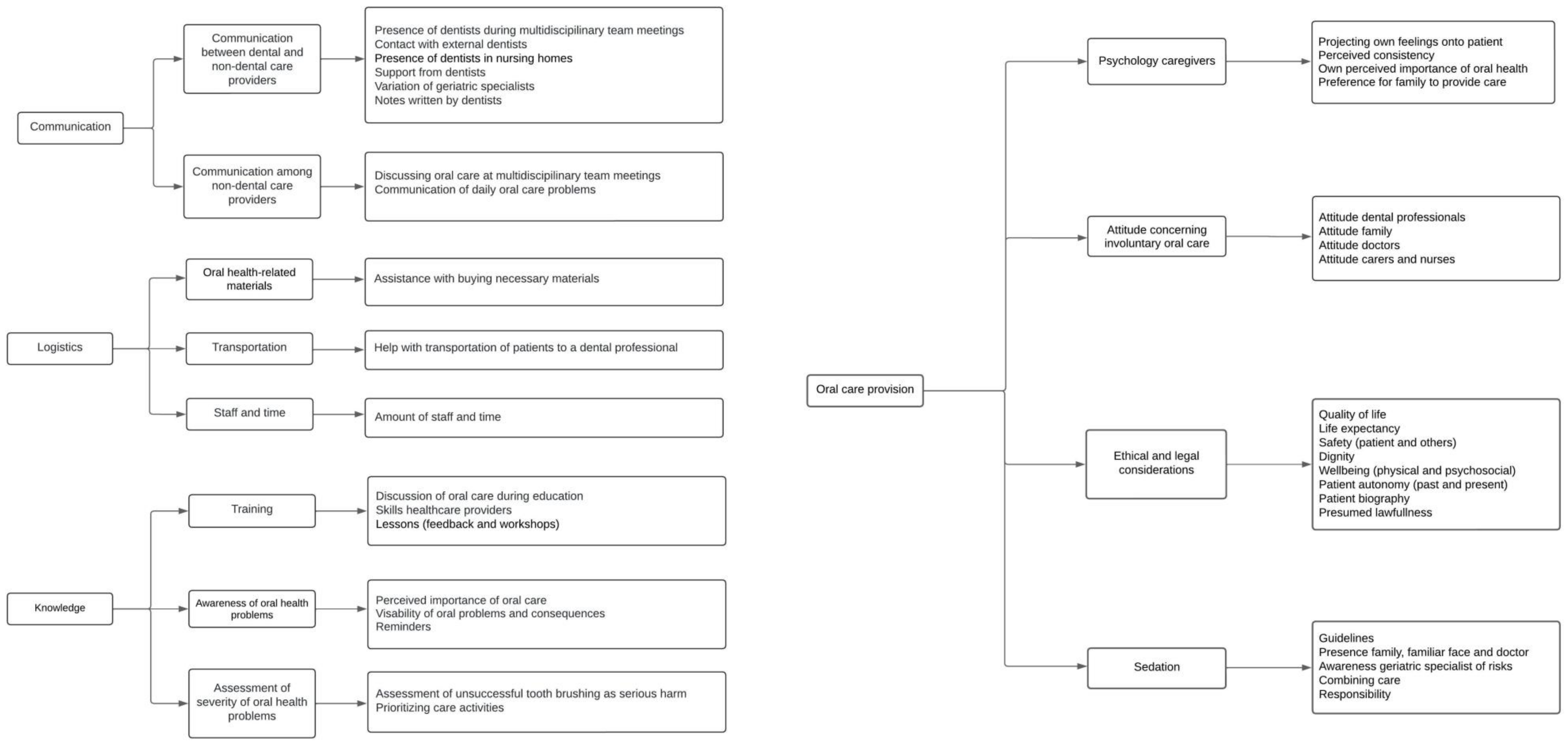

3. Results

3.1. Barriers and Facilitators

3.1.1. Communication

- (A)

- Communication between dental and non-dental care providers

“We are never invited to the multidisciplinary meetings, for example. We are kind of a separate entity that is a bit attached.”(Dentist, Interview 6)

“The question actually came from the care staff themselves, saying that brushing wasn’t going well. Do you have any tips or advice? So, then I came by, and I gave those tips.”(Dental Hygienist, Interview 2)

“You don’t have direct contact with the dentist. The family goes, and then it’s okay, someone has received special toothpaste. Then I just note that in the care plan for brushing with the special toothpaste. But otherwise, it’s always a matter of waiting to see, if someone has been to the dentist, what will we hear?”(Carer, Interview 4)

“…the dentist gave standard basic notes from their dental check-ups, and they were not personalized for the residents. They don’t give information if the lady needs assistance with oral care, whether she can do it herself or not, or if she needs to be flossed or not and how often, etcetera. And in care plans, it often didn’t even state whether someone has a prosthesis, a partial prosthesis, or no prosthesis.”(Nurse, Interview 4)

- (B)

- Communication between non-dental care providers themselves

“…but maybe I don’t hear directly from what is happening in practice. We are similar to general practitioners, of course. We take action when there is a problem.”(Geriatric specialist, Interview 1)

“I have never mentioned in the report whether I have cleaned someone’s teeth or not.”(Carer, Interview 1)

“…the geriatric specialist is consulted for pain complaints. But regarding dental maintenance, we have never really discussed anything about this with the doctor.”(Nurse, Interview 5)

3.1.2. Logistics

- (A)

- Oral-health-related materials

- (B)

- Transportation

“Most people with dementia no longer drive. Sometimes, if the children live far away or they have a very small social network, and they need to go somewhere, that is often very complicated. People can no longer take a taxi by themselves because they do not understand how to call a taxi. And it is always nice when someone accompanies them to the dentist.”(Dementia case manager, Interview 2)

- (C)

- Staff and time

“I think that if we had the manpower, the time, and the budgets and things like that, we would address everything all at once right away. But I also know that from management’s perspective, that’s just not possible, and decisions are made about which group is going to be prioritized. We’re simply dealing with the heavy workload in healthcare. We also face illness and absenteeism.”(Nurse, Interview 3)

3.1.3. Knowledge

- (A)

- Training

“In my training as a carer, we had to brush each other’s teeth once, and that was it.”(Carer, Interview 5)

“…because essentially you are asking caregivers to start climbing Mount Everest, while they can’t even get up the Kardinge hill [30 m high].”(Dental hygienist, Interview 1)

“Yes, and I think it could be improved if we were given more tools on how to approach it—tips and tricks, so to speak, on what you can do to provide the best possible oral care. […] A clinical lesson or something by a dentist, maybe with some photos as well. How teeth can end up looking if not cared for, and the risks and consequences—people really need to become more aware of this.”(Nurse, Interview 1)

“It may also be a matter of knowledge about oral care. That is quite minimal. Looking back at my training to become a geriatric specialist, it [oral health] was only a very small part of the curriculum.”(Geriatric specialist, Interview 1)

“For 28 years, I invited all new geriatric specialists who joined my organization to come and observe for a morning. Not just observe—I put a white coat on them. I had them assisting me with suctioning and showed them what was present in the mouth, ideally during an extraction. Really being able to see and experience the patient, that you also want to suture. Just the whole process, from A to Z.”(Dentist, Interview 8)

- (B)

- Awareness of oral health problems

“I must say that oral care is often forgotten. That’s really how it is. A neglected stepchild who doesn’t receive enough attention.”(Case manager dementia, Interview 1)

“…and if there is any change in behavior, I think we don’t always consider whether pain from the jaw or dental elements might also play a role, and I must admit, we don’t have a very clear picture of that.”(Geriatric specialist, Interview 1)

“But I think that, in the end, they [non-dental care providers] don’t see the importance of it. Look, if you have a wound and it’s not properly cared for, people get sick from it, and then it’s very clear that someone can die from sepsis. But that is not at all so clear when it comes to dental care. […] A beard, you see that, right? If someone is unshaven, if someone has greasy hair, you see that, but I don’t see a filthy mouth, and people just don’t see it.”(Geriatric specialist, Interview 2)

“‘Well, if I have to brush involuntarily, that’s not allowed, so I don’t do it, right?’ They [other carers] take it [not performing oral care] very lightly, until we have another themed month or something about oral care. Then they think: ‘oh yes, oral care, let me look into that again’.”(Nurse, Interview 2)

- (C)

- Assessment of severity of oral health problems

“A serious harm? Honestly not, but it is of course important that it doesn’t happen regularly. Especially if the person still has their own teeth, because you will get all sorts of spots or blisters and things like that. You just want to prevent that.”(Carer, Interview 5)

Interviewer: “If we look at other care, they [individuals with dementia] don’t shower or don’t remove incontinence material. Would you then use some form of coercion if it really doesn’t work?”

Participant: “Yes, you would have to, because otherwise their buttocks would get damaged.”(Carer, Interview 1)

“…we all look at what is going on: why someone doesn’t want to be put under a shower. That could be because they are afraid of water. So, we will see if we can do it with washcloths. In any case, alternatives are considered, but when it comes to oral care, if someone doesn’t want to, [oral care is] stop[ped].”(Geriatric specialist, Interview 2)

3.1.4. Oral Care Provision

- (A)

- Psychology of caregivers

“If we pick up the clients for dental treatment and someone from the care staff or the residential assistant walks with them, and they, start saying things like ‘Well, you don’t have to be afraid’ or ‘I hope the molars won’t be pulled’ or ‘Better you than me’, then we are looking like what are you doing?”(Dental Hygienist, Interview 2)

“…well, then you have to put the toothbrush in the mouth of the patient. Yeah right, I’m really not going to do that, you wouldn’t want that for yourself either.”(Carer, Interview 1)

“I can’t imagine why people don’t do that [tooth brushing] in evening care, because you wouldn’t go to bed without brushing your teeth yourself, would you?”(Nurse, Interview 1)

“It also really depends on the care provider, of course. One care provider, you see them smile at you once, and you think, ‘Well, you never touched a toothbrush yourself, so how important do you think it is for yourself? So how important do you think it is for someone else?’”(Dentist, Interview 5)

“...and to be very honest, look, if the family does it with a bit of gentle coercion, so to speak, I find that less troubling than if we have to do it ourselves.”(Nurse, Interview 2)

- (B)

- Attitudes

“When I provide involuntary care, I really only do extractions.”(Dentist, Interview 3)

“I have sometimes chosen, in consultation with the doctor, to use Dormicum and fill as many teeth as possible so that they are easier to keep clean and the prognosis for the teeth is better, so they last longer.”(Dentist, Interview 2)

“…you also help someone get rid of an infection that can have a very negative impact on their health, but that is sometimes just difficult to explain to the family, especially if the family or caregivers themselves are not keen on the dentist. Then they say, ‘Oh, how sad, do I really have to put my mother through that?’”(Dentist, Interview 2)

“ …or the doctor who usually finds extractions fine, but when it can’t be done without sedation, they back out, at least my doctors do. They don’t dare to do that. That’s a bridge too far for them.”(Dentist, Interview 6)

Participant: “I think, a set of teeth that deteriorates, well, that’s okay in a year.”

Interviewer: “So you’re saying that it doesn’t actually need to be brushed if someone has a year to live?”

Participant: “It doesn’t need to be, no.”(Geriatric specialist, Interview 1)

“I do think that dental professionals are not very popular here, it indeed has a lot of negative influence on the ward or the housing units when they come here.”(Nurse, Interview 7)

- (C)

- Ethical and legal considerations

“So, what are you going to do to those people who don’t want anything anymore in those two years? What are you going to do to them?”(Dentist, Interview 3)

“We must also think of our own safety. And if someone just starts hitting and kicking, then it’s simply, yes, that’s it.”(Carer, Interview 2)

“…she left a trail of saliva and blood in the nursing home. At that moment, we thought something had to be done, because she was contaminating the nursing home and was also a danger to the other residents. […] I extracted teeth for her, and in the end, two weeks later, she had really improved a lot.”(Dentist, Interview 4)

“… in the light of dignity. Then I think, someone has always paid so much attention to it [their teeth]. Who are you, then, to decide, because that is essentially what you are doing, that someone no longer finds it important?”(Dental Hygienist, Interview 1)

“If you need two people to completely hold the head in place to fix something, that’s a struggle. Then I stop, and we discuss again. This is a bit dehumanizing.”(Dentist, Interview 6)

“…we had such a strong suspicion that something was going on in the mouth, something we couldn’t identify, which caused the person to lose weight, stop eating, become irritable, and so on. So, we thought, we need to look inside the mouth.”(Nurse, Interview 2)

“… I’m talking about someone who had very bad breath. That becomes a burden for the entire department and the care staff. When they come by or sit at the table, everyone thinks ‘aaaargh,’ and then it becomes a social problem.”(Dentist, Interview 8)

“We can’t suddenly start treating them like children. They are still in charge, so to speak, of their own bodies.”(Carer, Interview 2)

“…you sometimes see that people have invested a lot in their teeth or they have spent a lot of energy, time, money, and so on, to maintain good teeth. And if you then handle it very lazily because you think, ‘Yes, someone shows resistance,’ or you stop at the slightest resistance, I think, ‘Is that really justifiable in light of their past autonomy?’”(Dental Hygienist, Interview 1)

“A lady who refused all care and whose medical history stated that she had been abused at a young age. I don’t know exactly what happened, but it was something physical, which made her not want to be touched by anyone. […] I knew she still had a few teeth, at least, we thought so, but no one had ever looked inside her mouth. And we didn’t want to look either, because she had refused to be touched her entire life. So, we respected that.”(Dentist, Interview 4)

“We take people’s life history into account. If someone has been in a concentration camp, for example, this becomes incredibly important, their autonomy and ability to do things for themselves. This can be so deeply ingrained. We actually had someone like that, where even basic daily activities were incredibly challenging because it meant entering their personal space. And when it comes to the mouth, that’s even more so…”(Geriatric specialist, Interview 3)

“… they [carers] now think, Care and Coercion Act, oh, it’s not allowed, I won’t do it.”(Nurse, Interview 2)

“How do we assess, what is someone’s life expectancy? What is the level of suffering if we don’t do it versus if we do? How do these factors relate to each other? Is what we are doing proportionate? I can’t provide a checklist for this in advance because it’s so individually determined.”(Geriatric Specialist, Interview 3)

“Well, I think if a tooth were to be inflamed, and you would expect quite severe symptoms from that, it [involuntary care] is something worth considering. And I can’t just say one, two, three, ‘we’ll do it.’ Of course, there are multiple factors that are important in such a case.”(Nurse, Interview 5)

“...then I’m willing to wedge my mirror in just a little bit to briefly check if there’s any acute issues, and then I accept it [care-resistant behavior] because these are often people who have a limited life expectancy anyway.”(Dentist, Interview 4)

- (D)

- Sedation

“I really like to be present when someone is going to be sedated because then you are much more involved and can treat at the right time. The last time it happened to me, they said they gave it at 12:30, and we were only called at 1:00, and by then the sedation had practically worn off.”(Dentist, Interview 1)

“... the person who was sitting next to him, supposedly monitoring his breathing, who had administered the midazolam [sedative], turned out to be a personal assistant, an intern, so not someone who was allowed to do that at all. […] I actually think that our protocols just need to be more watertight, so that you have well-documented responsibility for both the doctor and the nurses. So that they themselves have also seen on paper what their responsibilities are during the administration of midazolam.”(Dentist, Interview 7)

“…I’ve arranged everything. And then, I go to check. No, there is no doctor at all. There is no doctor. Didn’t we agree that today? ‘No, well, but we often do little puffs in the nose’, so I say, ‘No, I don’t want that’.”(Dentist, Interview 3)

“I am not going to hug someone, but a daughter or a granddaughter will. So, they can really help them calm down, which I always find nice.”(Dentist, Interview 3)

“…that lack of knowledge is also present in my profession, those who say: ‘give midazolam,’ they don’t know about the phenomenon of respiratory depression either.”(Geriatric specialist, Interview 2)

“…it’s not just about the mouth. Often, it’s also the ingrown toenail or if they need to be bathed daily, which also doesn’t work out. So, there is often much more going on, and they are frequently given midazolam for other reasons as well. I always try to combine it.”(Dentist, Interview 7)

“If I know that they have taken that pill, I don’t like it because, what if they have problems? After they have been sedated, am I responsible at that moment? Is the care responsible at that moment? I think that is an important issue. Is it because I am looking into their mouth again that they become extra nervous and then have breathing problems? I don’t know, I find it quite difficult.”(Dentist, Interview 3)

4. Discussion

Strengths and Weaknesses

5. Conclusions

Recommendations

- Designate nurses and train them with specific expertise in oral health to help monitor oral health in the workplace and improve communication between dental and non-dental care providers.

- Involve dental care professionals in MDMs.

- Organize training for care providers regarding (1) managing care-resistant behavior and finding voluntary ways to provide care, (2) the importance of good oral health and tips/tricks for providing oral care, and (3) more training on the law to prevent it from being used as an excuse.

- Make sure that a shift in attitude is discussed as this is necessary to make sure that oral care is treated the same as non-dental ADL-care.

- Provide or design clear guidelines and protocols for sedation and daily oral care provision (for instance, after how many failed attempts to provide daily oral care should it be considered a problem?).

- Perform more research on providing involuntary oral care, including practical examples where the decision was made to provide involuntary oral care and the reasoning behind it.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Alzheimer Nederland. Wat Is Dementie? Available online: https://www.alzheimer-nederland.nl/dementie (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Hugo, J.; Ganguli, M. Dementia and Cognitive Impairment: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2014, 30, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeksema, A.R.; Peters, L.L.; Raghoebar, G.M.; Meijer, H.J.A.; Vissink, A.; Visser, A. Oral health status and need for oral care of care-dependent indwelling elderly: From admission to death. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 2189–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, M.S.; Hollaar, V.R.Y.; van der Maarel-Wierink, C.D.; van der Putten, G.; Satink, T. Care-resistant behaviour during oral examination in Dutch nursing home residents with dementia. Gerodontology 2023, 40, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, W.M. The life course and oral health in old age. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2023, 54, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oral Health Across the Lifespan: Older Adults. In Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578296/ (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Dörfer, C.; Benz, C.; Aida, J.; Campard, G. The Relationship of Oral Health with General Health and NCDs: A Brief Review. Int. Dent. J. 2020, 67, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willumsen, T.; Karlsen, L.; Naess, R.; Bjørntvedt, S. Are the Barriers to Good Oral Hygiene in Nursing Homes within the Nurses or the Patients? Gerodontology 2012, 29, e748–e755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koninkrijksrelaties M van BZ en. Wet Zorg en Dwang Psychogeriatrische en Verstandelijk Gehandicapte Cliënten. Available online: https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0040632/2021-11-06#Hoofdstuk1_Artikel2 (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Hem, M.H.; Gjerberg, E.; Husum, T.L.; Pedersen, R. Ethical Challenges When Using Coercion in Mental Healthcare: A Systematic Literature Review. Nurs. Ethics 2018, 25, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lov om Kommunale Helse- og Omsorgstjenester m.m. (Helse- og Omsorgstjenesteloven)—Lovdata. Available online: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2011-06-24-30 (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Jonker, M.; Engelsma, C.; Manton, D.J.; Visser, A. Decision-Making concerning Involuntary Oral Care for Older Individuals with Dementia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoben, M.; Clarke, A.; Huynh, K.T.; Kobagi, N.; Kent, A.; Hu, H.; Pereira, R.A.; Xiong, T.; Yu, K.; Xiang, H.; et al. Barriers and facilitators in providing oral care to nursing home residents, from the perspective of care aides: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 73, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weening-Verbree, L.F.; Schuller, A.A.; Cheung, S.L.; Zuidema, S.U.; Van Der Schans, C.P.; Hobbelen, J.S.M. Barriers and facilitators of oral health care experienced by nursing home staff. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellander, L.; Angelini, E.; Andersson, P.; Hägglin, C.; Wijk, H. A preventive care approach for oral health in nursing homes: A qualitative study of healthcare workers’ experiences. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsell, M.; Sjögren, P.; Kullberg, E.; Johansson, O.; Wedel, P.; Herbst, B.; Hoogstraate, J. Attitudes and perceptions towards oral hygiene tasks among geriatric nursing home staff. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2011, 9, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gu, L.; Chen, W.; Qiao, M.; Wang, M.; Huang, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L. Factors associated with nurses’ attitudes for providing oral care in geriatric care facilities: A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.Y.; Walsh, L.J.; Pradhan, A.; Yang, J.; Chan, P.Y.; Silva, C.P.L. Interprofessional collaboration utilizing oral health therapists in nursing homes: Perceptions of oral health therapists and nursing home staff in Singapore. Spec. Care Dent. 2023, 43, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arweiler, N.B.; Netuschil, L. The Oral Microbiota. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 902, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Selwitz, R.H.; Ismail, A.I.; Pitts, N.B. Dental Caries. Lancet 2007, 369, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmers, E.; Janssens, L.; Phlypo, I.; Vanhaecht, K.; Mello, J.D.A.; De Visschere, L.; Declerck, D.; Duyck, J. Perceptions on Oral Care Needs, Barriers, and Practices Among Managers and Staff in Long-Term Care Settings for Older People in Flanders, Belgium: A Cross-sectional Survey. Innov. Aging 2022, 6, igac046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjellestad, Å.; Oksholm, T.; Alvsvåg, H.; Bruvik, F. Autonomy conquers all: A thematic analysis of nurses’ professional judgement encountering resistance to care from home-dwelling persons with dementia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moermans, V.R.; Mengelers, A.M.; Bleijlevens, M.H.; Verbeek, H.; de Casterle, B.D.; Milisen, K.; Capezuti, E.; Hamers, J.P. Caregiver decision-making concerning involuntary treatment in dementia care at home. Nurs. Ethics 2022, 29, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddis-Regan, A.; Abley, C.; Exley, C.; Wassall, R. Dentists’ Approaches to Treatment Decision-Making for People with Dementia: A Qualitative Study. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2023, 9, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1. What is your work function? How long have you been doing this job? |

| 2. What does a working day look like for you? |

| 3. In what way are you involved in the oral care of residents? |

| 4. Do you ever deal with residents who show care-resistant behavior toward oral care? What do you do in such cases? |

| 5. What are your experiences with providing involuntary oral care? Can you give examples? Do you encounter certain issues (barriers) concerning involuntary oral care? What would make it smoother for you to perform involuntary oral care (facilitators)? |

| 6. What do you consider reasons to provide involuntary oral care as a last resort? What is your opinion concerning involuntary tooth brushing? |

| 7. What do you consider involuntary care? Can you give examples? |

| 8. Does the Care and Coercion Act play a role for you in providing involuntary oral care? How so? |

| 9. What is your age, what is your gender, and in what province do you work? |

| Occupation | Gender | Age |

|---|---|---|

| Dentist | Male | 79 |

| Dentist | Female | 43 |

| Dentist | Female | 58 |

| Dentist | Male | 60 |

| Dentist | Female | 34 |

| Dentist | Female | 47 |

| Dentist | Female | 41 |

| Dentist | Female | 65 |

| Dental hygienist | Female | 40 |

| Dental hygienist | Female | 35 |

| Dental hygienist | Female | 32 |

| Carer | Female | 43 |

| Carer | Female | 36 |

| Carer | Female | 57 |

| Carer | Female | 51 |

| Carer | Female | 37 |

| Carer | Female | 50 |

| Nurse | Female | 58 |

| Nurse | Female | 30 |

| Nurse | Female | 33 |

| Nurse | Female | 41 |

| Nurse | Female | 59 |

| Nurse | Female | 55 |

| Nurse | Female | 27 |

| Geriatric specialist | Male | 64 |

| Geriatric specialist | Male | 66 |

| Geriatric specialist | Female | 57 |

| Dementia case manager | Female | 32 |

| Dementia case manager | Female | 31 |

| General practitioner | Female | 55 |

| General practitioner | Female | 53 |

| General practitioner | Female | 46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jonker, M.; Engelsma, C.; Manton, D.J.; Visser, A. Barriers and Facilitators Concerning Involuntary Oral Care for Individuals with Dementia: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030460

Jonker M, Engelsma C, Manton DJ, Visser A. Barriers and Facilitators Concerning Involuntary Oral Care for Individuals with Dementia: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030460

Chicago/Turabian StyleJonker, Maud, Coos Engelsma, David J. Manton, and Anita Visser. 2025. "Barriers and Facilitators Concerning Involuntary Oral Care for Individuals with Dementia: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030460

APA StyleJonker, M., Engelsma, C., Manton, D. J., & Visser, A. (2025). Barriers and Facilitators Concerning Involuntary Oral Care for Individuals with Dementia: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030460