Individuals 45 Years and Older in Opioid Agonist Treatment: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Identify characteristics of OAT patients aged 45 and above;

- Explore key social, psychological, and medical factors influencing this population;

- Highlight gaps in current research regarding their needs and challenges.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

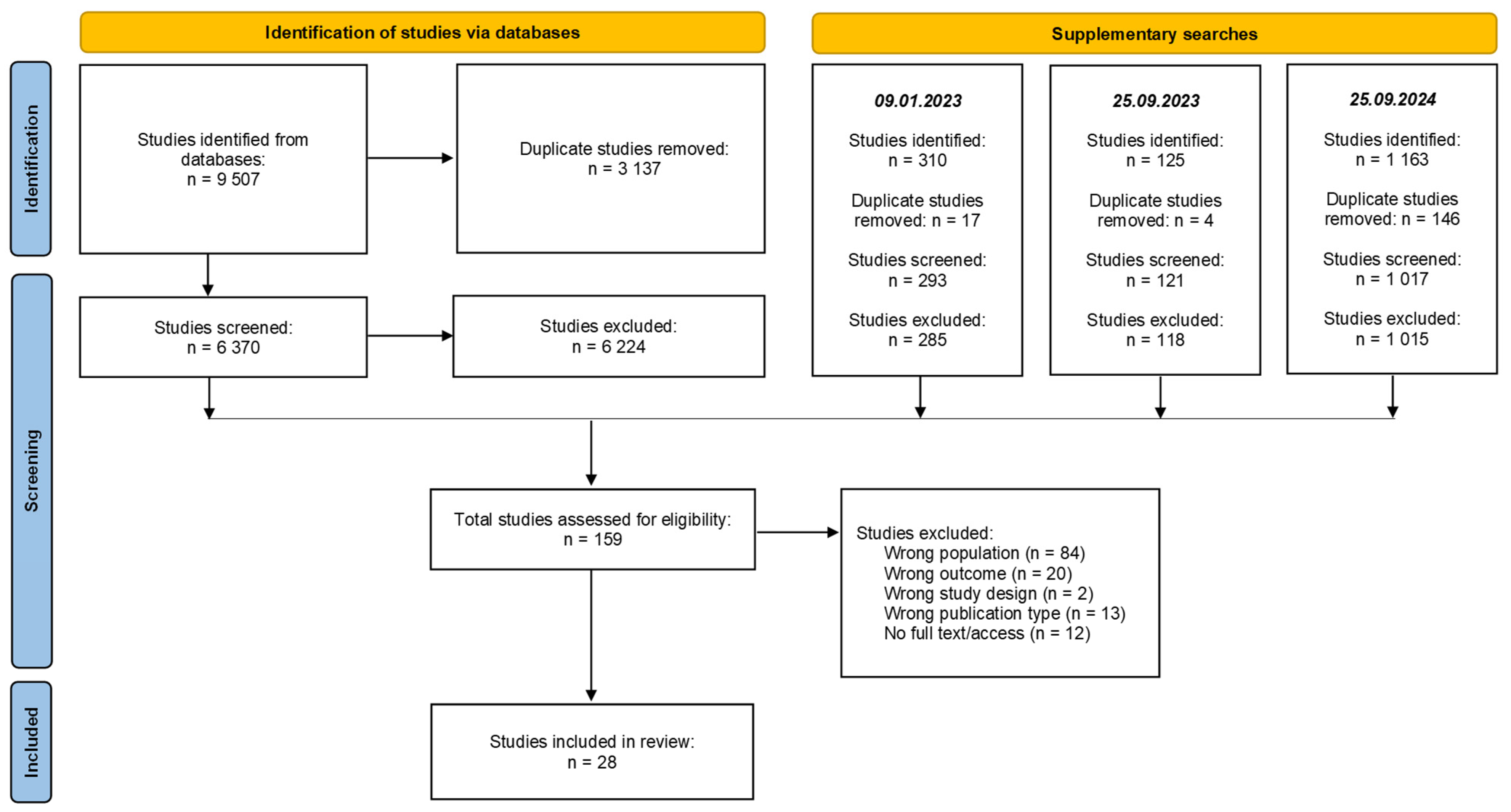

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Study Characteristics

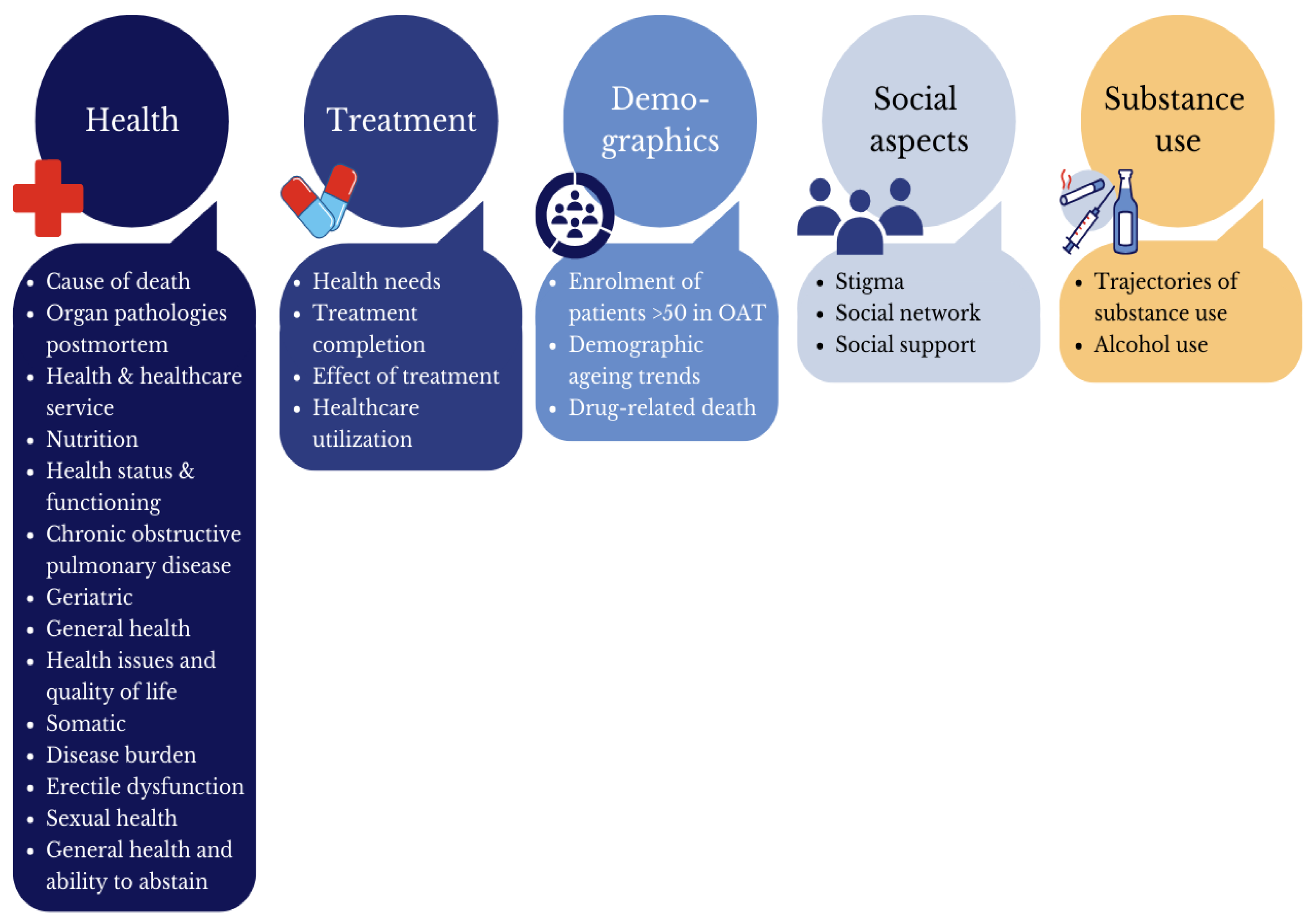

- Health

- Treatment

- Demographic factors

- Social aspects

- Substance use

4. Discussion

4.1. Health

4.2. Treatment

4.3. Demographics

4.4. Social Aspects

4.5. Substance Use

4.6. Methodological Aspects and Future Research Directions

4.7. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dole, V.P.; Nyswander, M.E. Heroin addiction-a metabolic disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 1967, 120, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barnett, P.G.; Rodgers, J.H.; Bloch, D.A. A meta-analysis comparing buprenorphine to methadone for treatment of opiate dependence. Addiction 2001, 96, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsi, K.F.; Lehman, W.K.; Booth, R.E. The effect of methadone maintenance on positive outcomes for opiate injection drug users. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2009, 37, 120–126. [Google Scholar]

- Larney, S.; Jones, N.R.; Hickman, M.; Nielsen, S.; Ali, R.; Degenhardt, L. Does opioid agonist treatment reduce overdose mortality risk in people who are older or have physical comorbidities? Cohort study using linked administrative health data in New South Wales, Australia, 2002–2017. Addiction 2023, 118, 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sordo, L.; Barrio, G.; Bravo, M.J.; Indave, B.I.; Degenhardt, L.; Wiessing, L.; Ferri, M.; Pastor-Barriuso, R. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: Systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2017, 357, j1550. [Google Scholar]

- Carew, A.M.; Comiskey, C. Treatment for opioid use and outcomes in older adults: A systematic literature review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 182, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, T.; Anzenberger, J.; Busch, M.; Gmel, G.; Kraus, L.; Krausz, M.; Labhart, F.; Meyer, M.; Schaub, M.P.; Westenberg, J.N.; et al. Opioid agonist treatment in transition: A cross-country comparison between Austria, Germany and Switzerland. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2024, 254, 111036. [Google Scholar]

- EUDA. European Drug Report 2023: Trends and Developments: European Union Drug Agency. 2023. Available online: https://www.euda.europa.eu/publications/european-drug-report/2023_en (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- EUDA. Opioid Agonist Treatment—The Current Situation in Europe (European Drug Report 2024); European Union Drugs Agency (EUDA): Lisbon, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Opioid Pharmacotherapy Statistics Annual Data Collection; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nesse, L.; Lobmaier, P.; Skeie, I.; Lillevold, P.H.; Clausen, T. Statusrapport 2022. Første år Med Nye LAR-Retningslinjer (Status Report 2022. First Year with New MAT Guidelines); Senter for rus- og avhengighetsforskning, SERAF: Oslo, Norway, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, M.T.; Hser, Y.I. Substance Use and Associated Health Conditions throughout the Lifespan. Public Health Rev. 2014, 35, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Murman, D.L. The Impact of Age on Cognition. Semin. Hear. 2015, 36, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Harada, C.N.; Natelson Love, M.C.; Triebel, K.L. Normal cognitive aging. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2013, 29, 737–752. [Google Scholar]

- Domzaridou, E.; Carr, M.J.; Millar, T.; Webb, R.T.; Ashcroft, D.M. Non-fatal overdose risk associated with prescribing opioid agonists concurrently with other medication: Cohort study conducted using linked primary care, secondary care and mortality records. Addiction 2023, 118, 2374–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaulen, Z.; Alpers, S.E.; Carlsen, S.-E.L.; Nesvag, S. Health and social issues among older patients in opioid maintenance treatment in Norway. Nord. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2017, 34, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsen, S.-E.L.; Lunde, L.-H.; Torsheim, T. Predictors of quality of life of patients in opioid maintenance treatment in the first year in treatment. Cogent Psychol. 2019, 6, 1565624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, I.; Kelly, P.J.; Deane, F.P.; Baker, A.L.; Goh, M.C.W.; Raftery, D.K.; Dingle, G.A. Loneliness among people with substance use problems: A narrative systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020, 39, 447–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, A.B.; Grella, C.E. Gender Differences Among Older Heroin Users. J. Women Aging 2009, 21, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd-Kvam, J.; Clausen, T. Practitioner perspectives on working with older patients in opioid agonist treatment (OAT) in Norway: Opportunities and challenges. Addict. Sci. Clin. Pract. 2024, 19, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsen, S.-E.L.; Gaulen, Z.; Alpers, S.E.; Fjaereide, M. Beyond medication: Life situation of older patients in opioid maintenance treatment. Addict. Res. Theory 2019, 27, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoz, S.; Carlson, G. Characteristics and treatment outcome of older methadone-maintenance patients. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2004, 12, 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofwall, M.R.; Brooner, R.K.; Bigelow, G.E.; Kindbom, K.; Strain, E.C. Characteristics of older opioid maintenance patients. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2005, 28, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursteler-MacFarland, K.M.; Herdener, M.; Vogel, M. Problems of Older Patients on Opioid Maintenance Treatment. Suchttherapie 2014, 15, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zolopa, C.; Høj, S.B.; Minoyan, N.; Bruneau, J.; Makarenko, I.; Larney, S. Ageing and older people who use illicit opioids, cocaine or methamphetamine: A scoping review and literature map. Addiction 2021, 117, 2168–2188. [Google Scholar]

- EUDA. Treatment and Care for Older Drug Users; European Union Drug Agency: Luxembourg, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rajaratnam, R.; Sivesind, D.; Todman, M.; Roane, D.; Seewald, R. The aging methadone maintenance patient: Treatment adjustment, long-term success, and quality of life. J. Opioid Manag. 2009, 5, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ayres, R.M.; Eveson, L.; Ingram, J.; Telfer, M. Treatment experience and needs of older drug users in Bristol, UK. J. Subst. Use 2012, 17, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Badrakalimuthu, V.R.; Tarbuck, A.; Wagle, A. Maintenance treatment programme for opioid dependence: Characteristics of 50+age group. Drugs Alcohol Today 2012, 12, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, C.M.; Roe, B.; Duffy, P.; Pickering, L. Self reported health status, and health service contact, of illicit drug users aged 50 and over: A qualitative interview study in Merseyside, United Kingdom. BMC Geriatr. 2009, 9, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Beynon, C.; Baron, L.; Hackett, A. Perceptions of food choices of people aged 50 and over in contact with a specialist drug service: A pilot qualitative interview study. J. Subst. Use 2013, 18, 499–507. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, N.G.; DiNitto, D.M.; Marti, C.N.; Choi, B.Y. Demographic and Clinical Correlates of Treatment Completion among Older Adults with Heroin and Prescription Opioid Use Disorders. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2022, 54, 440–451. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, K.O.; Rosen, D. “You’re Nothing But a Junkie”: Multiple Experiences of Stigma in an Aging Methadone Maintenance Population. J. Soc. Work. Pract. Addict. 2008, 8, 244–264. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.H.; Cotton, B.P.; Polydorou, S.; Sherman, S.E.; Ferris, R.; Arcila-Mesa, M.; Qian, Y.; McNeely, J. Geriatric Conditions Among Middle-aged and Older Adults on Methadone Maintenance Treatment: A Pilot Study. J. Addict. Med. 2022, 16, 110–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lintzeris, N.; Rivas, C.; Monds, L.A.; Leung, S.; Withall, A.; Draper, B. Substance use, health status and service utilisation of older clients attending specialist drug and alcohol services. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016, 35, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, A.; Macdonald, S.; Borycki, E.; Zhao, J. Hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes and depression among older methadone maintenance patients in British Columbia. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013, 32, 412–418. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, D.; Smith, M.L.; Reynolds, C.F. The Prevalence of Mental and Physical Health Disorders Among Older Methadone Patients. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 16, 488–497. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.L.; Rosen, D. Mistrust and Self-Isolation: Barriers to Social Support for Older Adult Methadone Clients. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 2009, 52, 653–667. [Google Scholar]

- Vallecillo, G.; Pedro-Botet, J.; Fernandez, S.; Román, I.; Elosua, R.; Camps, A.; Torrens, M.; Marrugat, J. High cardiovascular risk in older patients with opioid use disorder: Differences with the general population. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2022, 41, 1078–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.H.; Orozco, M.A.; Miyoshi, M.; Doland, H.; Moore, A.A.; Jones, K.F. Experiences of Aging with Opioid Use Disorder and Comorbidity in Opioid Treatment Programs: A Qualitative Analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2024, 39, 1673–1680. [Google Scholar]

- Grella, C.E.; Lovinger, K. 30-year trajectories of heroin and other drug use among men and women sampled from methadone treatment in California. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011, 118, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Grella, C.E.; Lovinger, K. Gender differences in physical and mental health outcomes among an aging cohort of individuals with a history of heroin dependence. Addict. Behav. 2012, 37, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bech, A.B.; Clausen, T.; Waal, H.; Šaltytė Benth, J.; Skeie, I. Mortality and causes of death among patients with opioid use disorder receiving opioid agonist treatment: A national register study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 440. [Google Scholar]

- Bech, A.B.; Clausen, T.; Waal, H.; Delaveris, G.J.M.; Skeie, I. Organ pathologies detected post-mortem in patients receiving opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder: A nation-wide 2-year cross-sectional study. Addiction 2021, 117, 977–985. [Google Scholar]

- Fareed, A.; Casarella, J.; Amar, R.; Vayalapalli, S.; Drexler, K. Benefits of Retention in Methadone Maintenance and Chronic Medical Conditions as Risk Factors for Premature Death Among Older Heroin Addicts. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2009, 15, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Grischott, T.; Falcato, L.; Senn, O.; Puhan, M.A.; Bruggmann, P. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among opioid-dependent patients in agonist treatment. A diagnostic study. Addiction 2019, 114, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Polydorou, S.; Ferris, R.; Blaum, C.S.; Ross, S.; McNeely, J. Demographic Trends of Adults in New York City Opioid Treatment Programs--An Aging Population. Subst. Use Misuse 2015, 50, 1660–1667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Medved, D.; Clausen, T.; Bukten, A.; Bjørnestad, R.; Muller, A.E. Large and non-specific somatic disease burdens among ageing, long-term opioid maintenance treatment patients. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2020, 15, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamathi, A.; Cohen, A.; Marfisee, M.; Shoptaw, S.; Greengold, B.; de Castro, V.; George, D.; Leake, B. Correlates of alcohol use among methadone-maintained adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009, 101, 124–127. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, M.; Millar, T.; Robertson, J.R.; Bird, S.M. Ageing opioid users’ increased risk of methadone-specific death in the UK. Int. J. Drug Policy 2018, 55, 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Ramli, F.F.; Shuid, A.N.; Pakri Mohamed, R.M.; Tg Abu Bakar Sidik, T.M.I.; Naina Mohamed, I. Health-Seeking Behavior for Erectile Dysfunction in Methadone Maintenance Treatment Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, F.F.; Tg Abu Bakar Sidik, T.M.I.; Naina Mohamed, I. Sexual Inactivity in Methadone Maintenance Treatment Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Assanangkornchai, S.; Liu, W.; Cai, L.; Li, F.; Tang, S.; Shen, J.; McNeil, E.B.; Chongsuvivatwong, V. Influence of social network on drug use among clients of methadone maintenance treatment centers in Kunming, China. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vikbladh, T.; Troberg, K.; Håkansson, A.; Dahlman, D. Healthcare utilization for somatic conditions among Swedish patients in opioid substitution treatment, with and without on-site primary healthcare. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, C.M. Drug use and ageing: Older people do take drugs! Age Ageing 2008, 38, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, T.; Waal, H.; Thoresen, M.; Gossop, M. Mortality among opiate users: Opioid maintenance therapy, age and causes of death. Addiction 2009, 104, 1356–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufort, A.; Samaan, Z. Problematic Opioid Use Among Older Adults: Epidemiology, Adverse Outcomes and Treatment Considerations. Drugs Aging 2021, 38, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Coccia, C.P.; Bertolini, A.; Sternieri, E. Methadone--metabolism, pharmacokinetics and interactions. Pharmacol. Res. 2004, 50, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCance-Katz, E.F.; Sullivan, L.E.; Nallani, S. Drug interactions of clinical importance among the opioids, methadone and buprenorphine, and other frequently prescribed medications: A review. Am. J. Addict. 2010, 19, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glancy, M.; Palmateer, N.; Yeung, A.; Hickman, M.; Macleod, J.; Bishop, J.; Barnsdale, L.; Trayner, K.M.; Priyadarshi, S.; Wallace, J.; et al. Risk of drug-related death associated with co-prescribing of gabapentinoids and Z-drugs among people receiving opioid-agonist treatment: A national retrospective cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 339, 116028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadnes, L.T.; Aas, C.F.; Vold, J.H.; Leiva, R.A.; Ohldieck, C.; Chalabianloo, F.; Skurtveit, S.; Lygren, O.J.; Dalgård, O.; Vickerman, P.; et al. Integrated treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs: A multicenter randomized controlled trial (INTRO-HCV). PLOS Med. 2021, 18, e1003653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M.J.; Elinore, F.M.-K. Co-occurring substance use and mental disorders among adults with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 197, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dugosh, K.; Abraham, A.; Seymour, B.; McLoyd, K.; Chalk, M.; Festinger, D. A Systematic Review on the Use of Psychosocial Interventions in Conjunction With Medications for the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. J. Addict. Dis. 2016, 10, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Shidlansik, L.; Adelson, M.; Peles, E. Knowledge and stigma regarding methadone maintenance treatment among personnel of methadone maintenance treatment and non-methadone maintenance treatment addiction facilities in Israel. J. Addict. Dis. 2017, 36, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van Boekel, L.C.; Brouwers, E.P.; van Weeghel, J.; Garretsen, H.F. Comparing stigmatising attitudes towards people with substance use disorders between the general public, GPs, mental health and addiction specialists and clients. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2015, 61, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huhn, A.S.; Berry, M.S.; Dunn, K.E. Review: Sex-Based Differences in Treatment Outcomes for Persons With Opioid Use Disorder. Am. J. Addict. 2019, 28, 246–261. [Google Scholar]

- Fung, H.H. Aging in Culture. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Mattson, M.; Lipari, R.N.; Hays, C.; Van Horn, S.L. A Day in the Life of Older Adults: Substance Use Facts. In The CBHSQ Report; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, A.D.; Chen, R.; Nielsen, S.; Zahra, E.; Degenhardt, L.; Santo, T.; Farrell, M.; Larance, B. Economic analysis of out-of-pocket costs among people in opioid agonist treatment: A cross-sectional survey in three Australian jurisdictions. Int. J. Drug Policy 2022, 99, 103472. [Google Scholar]

- Beller, J. Social Inequalities in Loneliness: Disentangling the Contributions of Education, Income, and Occupation. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241281408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, S.-E.L.; Isaksen, K.; Fadnes, L.T.; Lygren, O.J.S.; Åstrøm, A.N. Non-financial barriers in oral health care: A qualitative study of patients receiving opioid maintenance treatment and professionals’ experiences. Subst. Abus.Treat.Prev. Policy 2021, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krendl, A.C.; Perry, B.L. Stigma Toward Substance Dependence: Causes, Consequences, and Potential Interventions. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2023, 24, 90–126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Earnshaw, V.A. Stigma and substance use disorders: A clinical, research, and advocacy agenda. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 1300–1311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muller, A.E.; Skurtveit, S.; Clausen, T. Building abstinent networks is an important resource in improving quality of life. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017, 180, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gaeta Gazzola, M.; Carmichael, I.D.; Madden, L.M.; Dasgupta, N.; Beitel, M.; Zheng, X.; Eggert, K.F.; Farnum, S.O.; Barry, D.T. A cohort study examining the relationship among housing status, patient characteristics, and retention among individuals enrolled in low-barrier-to-treatment-access methadone maintenance treatment. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2022, 138, 108753. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, B.; Beynon, C.; Pickering, L.; Duffy, P. Experiences of drug use and ageing: Health, quality of life, relationship and service implications. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 1968–1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, R. Chronic Stress, Drug Use, and Vulnerability to Addiction. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2008, 1141, 105–130. [Google Scholar]

- Stellern, J.; Xiao, K.B.; Grennell, E.; Sanches, M.; Gowin, J.L.; Sloan, M.E. Emotion regulation in substance use disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 2023, 118, 30–47. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, N.H.; Kiefer, R.; Goncharenko, S.; Raudales, A.M.; Forkus, S.R.; Schick, M.R.; Contractor, A.A. Emotion regulation and substance use: A meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022, 230, 109131. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Individuals (aged 45 and above) undergoing treatment for OUD | Individuals in OAT under the age of 45 |

| Concept | Studies focusing on all aspects of life | Studies focusing solely on younger adults, other treatments (e.g., cancer therapy), or not related specifically to ageing in OAT |

| Context | Inpatient or outpatient settings, including primary care, addiction treatment centres, or healthcare settings in any country | Studies on individuals not in OAT |

| Study Design | Observational studies (prospective/retrospective) and qualitative studies (interviews, focus groups) | Abstracts, posters, annual meetings, editorial commentary, reviews, reports, grey literature, meta-analyses, case studies, interventional studies |

| Time Frame | No time restrictions were imposed | |

| Language | English, Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, or German | |

| EMBASE search sting | aged/OR middle aged, (aged or elder* OR aging OR ageing OR senior OR “older patient*”), opiate/OR methadone, buprenorphine/OR diamorphine, AND (maintenance OR replacement OR replacing OR substitution OR substitute* OR assisted OR medicated), ((opioid OR opioide OR opiate* OR methadone OR metadon OR buprenorfine OR buprenorphine OR buprenorphin OR diamorphine OR heroin OR heroine OR metadone) adj3 (maintenance OR replacement OR replacing OR substitution OR substitute* OR assisted OR medicated) |

| Study Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| U.S. | 13 (46.4) |

| UK | 4 (14.2) |

| Norway | 3 (10.7) |

| Malaysia | 2 (7.1) |

| Australia | 1 (3.6) |

| Canada | 1 (3.6) |

| China | 1 (3.6) |

| Spain | 1 (3.6) |

| Sweden | 1 (3.6) |

| Switzerland | 1 (3.6) |

| Author 1, Year, Country | Methodology, N, Sex, Age (Range, SD, Mean) | Rationale for Focusing on Older Adults and Age | Aims |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ayres et al., 2012, UK [32] | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews, focus group; descriptive design. N = 20; 85% men. Age range: 55–66. | (a) Increasing trend of older adults in drug treatment services; (b) Neglected and overlooked population. | 1. Explore health needs and treatment experiences; 2. Ideas for developing service. |

| Badrakalimuthu et al., 2012, UK [33] | Quantitative, retrospective cross-sectional design. Group comparison: <50 vs. >50. N = 92; 83% men. Age range: 50–73. | (a) To ensure adequate sample size for the study; (b) Similar age range used in previous studies. | 1. Explore characteristics of patients >50 entering treatment; 2. Compare these characteristics with those <50. |

| Bech et al., 2019, Norway [47] | Quantitative, national, observational study; registry data. N = 200; 74% men. Mean age: 48.9 (SD = 8.4, range 23–71). | (a) Norway has one of Europe’s oldest OAT populations; (b) Somatic causes of death are likely to rise as OAT patients age. | 1. Describe causes of death; 2. Estimate all-cause and specific crude mortality rates by age, OAT medication, and gender; 3. Explore characteristics associated with drug-induced death vs. other causes. |

| Bech et al., 2021, Norway [48] | Quantitative, national, cross-sectional design. N = 122; 75% men. Mean age: 48 (SD = 8.7, range 23–68). | (a) OAT patients are ageing; (b) Few post-mortem data on organ pathology in OAT patients over 40; (c) Few data on prevalence of enlarged organs. | 1. Document organ pathologies post-mortem; 2. Estimate the relationship between individual characteristics and pulmonary, cardiovascular, hepatic, or renal pathologies. |

| Beynon et al., 2009, UK [34] | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews; descriptive design. N = 10; 90% men. Age range: 54–61. | (a) Public health concern about older drug users; (b) Unique health challenges; (c) Underrepresentation in research. | 1. Identify substances used; 2. Assess self-reported health; 3. Examine contact with generic and specialist health services. |

| Beynon et al., 2013, UK [35] | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews; pilot study. N = 10; 90% men. Age range: 51–61. | (a) Age-related health changes require more attention; (b) Need to address nutritional deficiencies to improve health outcomes. | 1. Investigate diet perceptions; 2. Investigate influences on food choices; 3. Identify if body mass is considered in care planning. |

| Choi et al., 2022, USA [36] | Quantitative, national, cross-sectional design, retrospective cohort element. Group comparison: (a) primary heroin vs. prescribed opioids; (b) 55–64 vs. 65+. N = 127,034; 72% men. Age: >55. | (a) Rising cases of OUD among older adults from 2004–2015; (b) High prescription opioid use in older adults due to chronic pain; (c) Health risks associated with opioid use in older adults. | 1. Examine treatment completion rates by setting (detoxification, residential, and outpatient); 2. Identify factors associated with treatment completion; 3. Analyse substance use patterns; 4. Evaluate treatment characteristics. |

| Conner et al., 2008, USA [37] | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews; descriptive design. N = 24; 42% men. Age range: 50–60. | (a) Underrepresentation of older adults in stigma research; (b) Experiences of ageing methadone clients; (c) Healthcare disparities. | 1. Examine stigma experiences; 2. How multiple stigmas delay entry to substance abuse and mental health treatment. |

| Fareed et al., 2009, USA [49] | Quantitative, retrospective cohort study. N = 91; 98–100% men. Age 40+. Mean age: 57 (SD = 3) deceased; 57 (SD = 9) retained; 53 (SD = 6) dropped out. | (a) Experiences of the effects of ageing and opioid dependence; (b) Comorbidities compound the health risks associated with opioid dependence; (c) Premature mortality differs between older adults and younger patients. | 1. Identify key factors contributing to premature death; 2. Assess MMT effectiveness in reducing drug use and improving overall health outcomes; 3. How comorbid conditions and medical issues impact health and mortality. |

| Grella & Lovinger, 2011, USA [45] | Quantitative, longitudinal retrospective cohort design. Group comparison: Men vs. women. N = 343; 55.7% men. Mean age: 58.3 (SD = 4.9) men; 55.0 (SD = 4.1) women. | (a) Long-term outcomes and changes in drug use patterns; (b) Impact of childhood factors on heroin addiction; (c) Explore substance use disorders and ageing. | Examine long-term drug use trajectories in MMT. |

| Grella & Lovinger, 2012, USA [46] | Quantitative, longitudinal retrospective cohort design. Group comparison: (a) Men vs. women; (b) MMT vs. general population, N = 343; 55.7% men, Mean age: 58.3 (SD = 4.9) men; 55.0 (SD = 4.1) women. | (a) “Baby Boomer” health problems and service needs; (b) Rising substance use problem in adults 50+. | Assess overall health status and psychosocial functioning in older adults with a history of heroin dependence. |

| Grischott et al., 2019, Switzerland [50] | Quantitative, cross-sectional design. Group comparison: Older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) vs. younger adults without COPD. N = 125; 76% men. Mean age: 45.1 (SD = 9.3, range 22–65). | (a) Explore chronic illnesses in ageing OAT patients; (b) Older adults face age-related health issues. | 1. Estimate COPD prevalence and risk factors; 2. Establish the distribution of airflow obstruction severity; 3. Compare COPD rates in different age groups with the general population; 4. Assess willingness to adopt lifestyle changes and use therapies among OAT patients with COPD. |

| Han et al., 2015, USA [51] | Quantitative, descriptive retrospective cohort design. N = 37,038 (1996); 40,328 (2003); 34,270 (2012); 66–69% men for all ages. Five age groups (≤40, 41–49, 50–59, 60–69, and ≥70). | (a) Variability in age cut-offs in previous studies; (b) Studies using large national datasets generally defined older adults as those aged 50 or 55 old. | 1. Examine age trends in older adults in OAT programmes in New York; 2. Characterize demographics, substance use, and physical impairments. |

| Han et al., 2022, USA [38] | Quantitative, descriptive cross-sectional design. Group comparison: MMT vs. national population. N = 47; 76.6% men. Mean age: 58.8 (SD = 5.8, range 50–75). | (a) MMT individuals ≥50 are more likely to have age-related health conditions and impairments; (b) Older adults have unique healthcare needs compared to younger people; (c) The age range involves prolonged opioid use, increasing vulnerability to geriatric conditions. | Determine prevalence of geriatric conditions in older MMT adults. |

| Han et al., 2024, USA [44] | Qualitative, descriptive phenomenological design. N = 36 OUD; 69.4% men. Mean age: 63.4 (SD = 5.1, range 55–77). | (a) A national initiative to enhance care for older adults by creating age-friendly health systems grounded in evidence-based geriatric principles; (b) a first step to developing age-friendly OUD models of care. | 1. To explore the ageing experience with OUD; 2. Barriers to medical care for older adults who receive care in OTPs. |

| Lintzeris et al., 2016, Australia [39] | Quantitative, cross-sectional design. Group comparison: Older vs. younger adults. N = 99 in the older group (n = 69 in OAT, n = 30 in alcohol treatment); 74% men. Mean age: 55 (SD = 4.5, range 50–71). | (a) More older patients in drug and alcohol treatment in Australia; (b) Projected rise in adults 50+ due to longer life expectancy and higher substance use rates; (c) Address health and social consequences of substance use in older adults. | 1. Examine substance use, health, cognition, social function, and health service use in older clients (≥50 years); 2. Compare these measures with younger clients. |

| Lofwall et al., 2005, USA [23] | Quantitative, cross-sectional design. Group comparison: 50–66 vs. 25–34 years old. N = 41 older participants (total n = 67); 51% men in the older group, 58% in the younger group. Mean age: 53.9 (SD = 0.6, range 50–66). | (a) The “Baby boomer” generation has higher substance use rates; (b) Substance use problems in older adults are an “invisible epidemic”; (c) Rising need for specific treatment for older adults; (d) Lack of understanding of non-alcohol drug use in older adults; (e) Identify specific challenges and treatment needs for older adults in substance abuse services. | 1. Compare older vs. younger opioid-dependent patients on psychiatric, substance use, medical, legal, and psychosocial variables; 2. Compare their health status to age- and sex-matched U.S. norms. |

| Maruyama et al., 2013, Canada [40] | Quantitative, case-control design. Group comparison: MMT patients vs. non-MMT patients. N = 199 MMT patients (total n = 398); 71.9% men. Mean age: 59.4 (SD = not given; 50+). | (a) Limited research on older MMT patients’ health compared to the general population; (b) Tailored healthcare services needed for older patients; (c) Care coordination issues due to the separation between family and methadone doctors; (d) Older patients face barriers to accessing primary healthcare and social services. | Compare prescription rates for hypertension, COPD, diabetes, and depression between MMT patients vs. matched controls. |

| Medved et al., 2020, Norway [52] | Quantitative, cross-sectional design. N = 156; 59.6% men. Mean age: 47.9 (SD = 7.1, range 31–64). | (a) Increasing age of OAT patients in Norway; (b) Chronic somatic health conditions increase with ageing; (c) Lack of data on long-term OAT patients’ somatic health needs. | 1. Identify chronic conditions, health care use, and treatment satisfaction; 2. Explore self-reported somatic disease burden and its associated factors. |

| Nyamathi et al., 2009, USA [53] | Quantitative, cross-sectional design. Group comparison: (a) ≥50 years vs. <50 years; (b) MMT moderate vs. heavy alcohol users; (c) Fair/poor vs. good/excellent health status. N = 190; 57.5% men. Age range: 18–55 (62% 50+). | No rationale for focusing on older patients; but dichotomized age at 50 for analysis purposes. | 1. Describe alcohol use prevalence among MMT patients; 2. Assess correlates of alcohol use, including demographics, health care use, social support, psychological resources, and risk factors. |

| Pierce et al., 2018, UK [54] | Quantitative, retrospective national cohort study. Group comparison: 18–24; 25–34; 35–44; 45–64 years old. N = 129,979; 77% men of the n = 1266 drug-related deaths (DRDs). Age range: 18–64 at inclusion. | (a) Methadone-specific DRDs increase with age; (b) Older opioid users more likely to have comorbid physical and mental health conditions; (c) Methadone’s pharmacodynamics vary with age; (d) Need for targeted monitoring and interventions for older methadone clients. | 1. Analyse demographic risk factors affecting hazard ratio for DRDs, methadone-specific DRDs, and heroin-specific DRDs; 2. Adjust analysis for treatment periods and declared substance misuse; 3. Pool age-related hazard ratios for methadone-specific deaths from the Scotland and England cohorts. |

| Ramli et al., 2019, Malaysia [55] | Quantitative, questionnaire-based study, cross-sectional design. N = 50; 100% men. Age 18+. Mean age: 47.3 (SD = 7.5) in erectile dysfunction treatment, 51 (SD = 10.2) in no treatment. | No rationale for focusing on older patients but examined age associations with treatment-seeking behaviour. | 1. Examine health-seeking behaviour for erectile dysfunction among MMT patients; 2. Assess factors and effectiveness of erectile dysfunction treatment-seeking behaviour. |

| Ramli et al., 2020, Malaysia [56] | Quantitative, cross-sectional design. N = 271; 100% men. Mean age: 48.8 (SD = 9.7, range 25–71). | (a) Sexual activity decreases with age in the general population; (b) MMT is linked to sexual dysfunction, but knowledge of sexual inactivity is limited. | Determine prevalence and risk factors for sexual inactivity. |

| Rosen et al., 2008, USA [41] | Quantitative, cross-sectional design. N = 140; 64.3% men. Mean age: 53.9 (SD = 40.1, range 50–67). | (a) Substance abuse among older adults is a growing public health issue; (b) Ageing opiate users face exacerbated health problems and social isolation; (c) Understanding comorbid conditions is crucial for serving an ageing population. | 1. Document general medical and mental health disorders; 2. Evaluate the ability to remain abstinent later in life. |

| Shen et al., 2018, China [57] | Quantitative, cross-sectional design. N = 324; 76.9% men. Mean age: 45.2 (SD = 6.3; 20+). | Age emerged as a key variable in analysing MMT clients’ drug use behaviours. | 1. Examine social network characteristics; 2. Explore relationships between social networks and drug use behaviours; 3. Identify protective and risk factors in social networks affecting drug use; 4. Provide insights into social networks and drug use. |

| Smith et al., 2009, USA [42] | Qualitative, descriptive design. N = 24; 41.7% men. Mean age: 58.4 (range 52–68). | (a) National data show significant adults over 50 receiving treatments for heroin use; (b) More older substance users are seeking help; (c) Age-related issues and loss of social support impact treatment. | Explore how older methadone patients’ experiences and views affect their use and expansion of social supports to stay abstinent. |

| Vallecillo et al., 2022, Spain [43] | Quantitative, cross-sectional design. Group comparison: MMT cohort vs. general population. N = 99; 72.7% men. Mean age: 55.7 (SD = 4.7; 50+). | Cardiovascular risk in older patients with opioid use disorder. | 1. Compare cardiovascular risk factors and global risk in OUD adults aged >50 with the general population; 2. Assess the efficacy of calibrated functions for risk. |

| Vikbladh et al., 2022, Sweden [58] | Quantitative, retrospective survey, cross-sectional design. N = 190; 64–72% men. Mean age: 46. On-site public healthcare group (SD = 10.6, range 25–63). | (a) Age correlated with more comorbidities and cognitive impairment; (b) More pronounced chronic and severe diseases; (c) Understanding healthcare use in older patients. | 1. Assess healthcare utilization for somatic conditions in OST patients; 2. Compare healthcare use among OST patients with and without on-site public healthcare. |

| Themes | Key Results |

|---|---|

| Health | |

| Bech et al., 2019, Norway [47] | The average age at death was 48.9 years. Causes of death: 45% somatic, 42% drug-induced, and 12% violent. Lower drug-induced death risk with older age and higher comorbidity. Somatic death rates doubled for patients over 50 compared to those aged 41–50. Higher mortality rate among men than women. Methadone users had twice the mortality rate of buprenorphine users. Most deaths occurred at home. |

| Bech et al., 2021, Norway [48] | Older age was linked to pulmonary, cardiovascular, and renal pathology, but not liver pathology. Cardiovascular and renal risks remain higher in older age, even after adjusting for BMI and sex. A total of 91% (n = 48) had a disease in at least one organ system; 76% (n = 40) had diseases affecting two or more organ systems. |

| Beynon et al., 2009, UK [34] | Heroin was often used together with alcohol, cannabis, LSD, amphetamine, cocaine, crack, and mushrooms. Common physical health issues: circulatory, respiratory, pneumonia, diabetes, hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, overdose, vein damage; about half had hepatitis C. Prevalent mental health issues: depression, loneliness, anxiety, cognitive impairment, dementia; short-term memory issues linked to age and substance use, including alcohol. Negative experiences in hospital settings: stigma, poor pain management (especially in palliative care), and low expectations of specialist services. |

| Beynon et al., 2013, UK [35] | Most rated their health as poor and had low-quality, limited-quantity diets, often opting for easily prepared foods, and rarely cooking due to financial and dental issues. Minimal intake of fruit and vegetables. A total of 50% of participants used illicit drugs, including heroin, crack, and cannabis, while most consumed alcohol and used prescriptions. All smoked daily. Reported various health issues: infections, circulatory and respiratory problems, pain, weight issues, liver cirrhosis, and headaches. BMI was not included in care planning activities. |

| Grella & Lovinger, 2012, USA [46] | General health status: A total of 47.8% reported fair or poor, 4% reported excellent health. Gender difference: More women reported poor health than men (27.3% vs. 8.4%) and faced more health conditions including heart disease, circulatory problems, asthma, bladder issues, colitis/bowel problems, arthritis, and chronic headaches, as well as higher levels of distress. Functional score: Lower scores in physical role functioning, bodily pain, general health, energy and fatigue, and social function compared to the general population. |

| Grischott et al., 2019, Switzerland [50] | Many older participants were smokers or had pulmonary symptoms. A total of 15% had undiagnosed COPD; 30% exhibited post-bronchodilator airflow limitation, indicating COPD. COPD patients were older (mean 51.0 vs. 42.6) and had greater lifetime exposure to tobacco and cannabis. Men over 40 in OAT had a 2.4 higher prevalence of COPD vs. Swiss ever-smokers. Older participants were highly open to pharmacological COPD treatment. |

| Han et al., 2022, USA [38] | Older OAT patients compared to the national cohort had higher rates of health issues (psychiatric disorders, chronic lung disease, cancer) and hospitalization, and greater physical challenges: falls, mobility impairment, and chronic pain |

| Lintzeris et al., 2016, Australia [39] | Over half reported liver disease and head injury, with common conditions including circulation issues in the legs, respiratory and gastrointestinal problems, hypertension, cardiac conditions, seizures, cancer, diabetes, and stroke. Most experienced falls in the past year, often resulting in injury or medical attention. Older patients had significantly lower physical health scores compared to those in alcohol-related treatment, indicating poorer physical health, quality of life, and a trend toward worse mental health. Few older adults received carer support, despite one-third struggling with daily tasks. A total of 15% of older patients reported violent crime victimization, compared to 5% of younger patients (ages 14–49). |

| Lofwall et al., 2005, USA [23] | Increased health issues: Older adults reported higher rates of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and bone/joint issues; and greater prescription medications compared to younger participants. Lower health-related quality of life: Older adults scored lower on measures of physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, and bodily pain. Their scores fell below population norms in all health-related quality of life domains, including physical and social functioning, mental health, vitality, and general health perception. |

| Maruyama et al., 2013, Canada [40] | Compared to the general population, older adults in OAT have higher rates of treatment for COPD and depression, and higher rates of hypertension and diabetes. |

| Medved et al., 2020, Norway [52] | Chronic condition: Nearly two-thirds had at least one chronic condition: HCV—the most common (52.9%), but rarely treated. Asthma—the next most common, with 80% receiving treatment. Others: high blood pressure, heart disease, COPD, and diabetes, with over 50% receiving treatment. Over 50% reported at least seven somatic complaints in the past six months, including reduced memory, headaches, indigestion, dizziness, dental issues, constipation, and joint pain. In this period, 81% visited a GP, and over 50% had additional somatic care visits. More than 60% were satisfied with OAT. |

| Ramli et al., 2019, Malaysia [55] | A total of 54% attempted ED treatment, 80% found it effective. A total of 48% did not seek information; 42% thought that “ED is not a serious condition”. No significant differences in effectiveness were noted across medical, self, and alternative treatments. |

| Ramli et al., 2020, Malaysia [56] | A total of 47.6% were sexually inactive, linked to older age and being single or divorced; no association with comorbidities, medications, or dose and duration of methadone treatment. Participants had hepatitis C and B, hypertension, HIV, and diabetes mellitus; 1.5% received hepatitis medication. |

| Rosen et al., 2008, USA [41] | Mental health: Depression is the most common disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder and generalized anxiety disorder are the most prevalent anxiety disorders. A total of 47% were on psychotropic medication for mental health issues. Women were twice as likely to have agoraphobia compared to men (20.8% vs. 9.8%). Physical health: 58% reported fair to poor physical health. Common health issues included arthritis (54.3%), hypertension (45%, significantly higher in men), and hepatitis C (49%). Age and health outcomes: OAT adults aged 50–54 had worse health outcomes than those aged 55–67 in the general population. Abstinence: Positive screening rates for substances remained similar one year after the study to pre-study levels, with 61.4% of respondents recording at least one positive result. |

| Vallecillo et al., 2022, Spain [43] | Health risks in older adults with OUD compared to the general population: higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk and increased incidence of tobacco smoking. In addition, common low HDL cholesterol, hypertriglyceridemia, atherogenic dyslipidaemia, and a high prevalence of abdominal obesity. |

| Treatment | |

| Ayres et al., 2012, UK [32] | Relationships with professionals: Positive relationships with healthcare professionals. Satisfied with prescriptions; preferred weekly collection over daily. Fear of losing prescriptions with GP changes, and supervised intake is viewed as humiliating. Treatment challenges: Poor hospital/dental care experiences, and unmet health needs. Limited access to additional treatment. Age-related concerns: Shame about drug use due to age, and age as a barrier to seeking help. Detoxification challenges with age and a need for age-specific services for older, stable OAT patients. |

| Choi et al., 2022, USA [36] | Patterns by group: Racial/ethnic minorities had lower odds of completing outpatient treatment. The heroin group had a higher rate of cocaine/crack use; more often included in treatment plans; legal referrals predicted treatment completion. The prescribed opioids group had higher rates of benzodiazepine/tranquillizer use and having a bachelor’s degree increased the odds of completing treatment. Influence of OAT: OAT was linked to higher odds of completing residential treatment but lower odds of completing detoxification and outpatient treatment. Outcomes by age: Older adults (65+) with prescribed opioids had higher odds of completing residential treatment than those aged 55–64. |

| Fareed et al., 2009, USA [49] | Retention in methadone treatment reduced drug-related, psychiatric, medical, and legal issues, with a trend toward fewer alcohol-related problems. Discontinuation of treatment did not demonstrate improvements, except for a slight reduction in family issues. Targeting interventions aimed at lifestyle risk factors and comorbid medical conditions, such as nicotine dependence and diabetes mellitus, could enhance health outcomes for older adults with opioid dependence. Premature death linked to diabetes and cancer before age 65. |

| Han et al., 2024, USA [44] | Chronic diseases were common, with 58% having hypertension, 25% hepatitis C, and 89% experiencing multiple chronic diseases. As they aged, participants often sought healthcare outside their OAT but faced discrimination, leading to mistrust of the system, hesitation to disclose substance use, and delays in routine care or reliance on emergency departments. Participants faced challenges ageing with OUD, including health declines, housing insecurity, and limited access to care due to transportation barriers. Reflecting on mortality sometimes motivated well-being efforts. Many favoured OATs for integrated services due to familiarity and reduced stigma. |

| Vikbladh et al., 2022, Sweden [58] | Primary healthcare utilization was associated with older age and being born in Sweden. Greater physical health concerns among on-site vs. regular primary healthcare users. Physical concerns: 52% had musculoskeletal diagnoses, one-third of the on-site group had gastrointestinal diagnoses, including constipation, and 62% reported neck, back, or extreme pain. In contact with secondary care: 84% of on-site users vs. 64% of regular users. |

| Demographics | |

| Badrakalimuthu et al., 2012, UK [33] | A total of 10% of newly enrolled patients were aged ≥60; the average first service contact at 41.4 years (range 21–65). A total of 11% initiated opiate use at age ≥ 50; 24% first contacted services at this age. Substance use: 73% methadone, 21% buprenorphine; 60% other substances; 31% multiple substances (82% used only two, mainly cannabis, benzodiazepines, or cocaine). A total of 66% had other prescriptions. High comorbidity: physical (54%) and mental (62%). A total of 37% had HCV. Treatment compliance was 86%. Participants under 50 years vs. aged ≥50: often single; unstable housing; higher rates of buprenorphine use; high-dose prescriptions; lower rates of blood-borne viruses and health issues. |

| Han et al., 2015, USA [51] | Demographic shift: Adults ≥50 constituted the majority in treatment over time, with an increasing proportion of females aged 50–59. Among patients over 60: high prevalence of White individuals compared to Black individuals. Higher rates of sight and mobility impairments among adults aged ≥50 vs. younger groups. |

| Pierce et al., 2018, UK [54] | The methadone-specific DRD rate was seven per 10,000 person-years overall, varying by age: 3.5 for 18–34, 8.9 for 35–44, 18 for 45+. The heroin-specific DRD rate was 12.5 per 10,000 person-years, higher in males. Being out of treatment doubled the risk of heroin-specific DRD and nearly quadrupled it, with a non-significant 20% decrease in methadone-specific DRD risk. Hazard ratios for methadone-specific deaths compared to ages 25–34 were 0.87 for under 25, 2.14 for 35–44, and 3.75 for 45+. |

| Social aspects | |

| Conner et al., 2008, USA [37] | Participants faced stigma in eight categories: drug addiction, ageing, psychotropic medications, depression, OAT, poverty, race, and status. Stigma with OAT, injection drug use, and age were most common. Men reported more stigmas than women. Stigma came from family, friends, rehab staff, and counsellors. Most participants faced multiple types of stigmas: 33% drug addiction and ageing; 25% depression and psychotropic medications; 33% drug addiction, OAT, and psychotropic medications; or drug addiction, ageing, and poverty; 66% drug addiction, ageing, psychotropic medications, and depression. Stigma and fear of treatment, including from psychiatrists, hindered service use. Age and poverty restricted access to mental health care. |

| Shen et al., 2018, China [57] | Composition of networks: Over 50% had parents in their social network, while one-third had friends or spouses. A total of 41% had older adults in their networks; 32% had individuals of the opposite sex. A total of 92% had at least one very close network member, most of whom provided financial or emotional support. A total of 24% had at least one network member who used substances with them. The majority reported positive or mixed experiences with clinic counsellors. |

| Smith & Rosen, 2009, USA [42] | Reluctance to trust others hindered social support expansion among older methadone clients. Key barriers: Trust issues: personal feelings and guilt impeded trust and relationship formation with staff, peers, and others. Personal loss: death of family and friends due to illness, violence, or drug-related causes. Relationship strain: conflict and abuse, particularly with family members using illegal drugs and turbulent intimate relationships. Self-isolating common among participants; limited social support. |

| Substance use | |

| Grella & Lovinger, 2011, USA [45] | Rapid decrease (25%): Highest female proportion (60%), least school-related issues (27%), older onset, lowest cocaine use (6%) but highest amphetamine (10%) and alcohol use (40%). Moderate decrease (15%): Fewest with conduct disorder (32%); decreased odds of heroin use Gradual decrease (35%): Highest rates of conduct disorder (52%) and antisocial personality disorder (49%), most time incarcerated (20%), youngest age of onset. No decrease (25%): Longest duration in OAT (38%). Low drug use (18%), late-onset increase (23%), early-onset increase (25%), gradual decrease (18%), and no decrease (16%). Heroin use varied among drug use groups, indicating complex patterns of heroin and other drug use. No single dominant pattern across the sample. |

| Nyamathi et al., 2009, USA [53] | Substance use: 51% heavy alcohol use, 46% heroin. In the past 30 days, older adults reported use of cocaine, marijuana, barbiturates, amphetamines, and hallucinogens. Heavy drinkers: had the highest rates of victimization; over half reported poor physical and emotional health; about half engaged in heavy drug use, unlike moderate drinkers. Older adults in fair or poor health were more than three times more likely to drink heavily than those in good to excellent health. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gaulen, Z.; Lunde, L.-H.; Alpers, S.E.; Carlsen, S.-E.L. Individuals 45 Years and Older in Opioid Agonist Treatment: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030458

Gaulen Z, Lunde L-H, Alpers SE, Carlsen S-EL. Individuals 45 Years and Older in Opioid Agonist Treatment: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030458

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaulen, Zhanna, Linn-Heidi Lunde, Silvia Eiken Alpers, and Siv-Elin Leirvaag Carlsen. 2025. "Individuals 45 Years and Older in Opioid Agonist Treatment: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030458

APA StyleGaulen, Z., Lunde, L.-H., Alpers, S. E., & Carlsen, S.-E. L. (2025). Individuals 45 Years and Older in Opioid Agonist Treatment: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030458