‘You’ve Just Got to Keep Pestering’: Barriers and Enablers of Attaining Continuity of Hepatitis C Care for People Transitioning Between Prison and Community Health Services in South-East Queensland, Australia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Ethical Approval

2.3. Sample and Recruitment

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Analytic Method

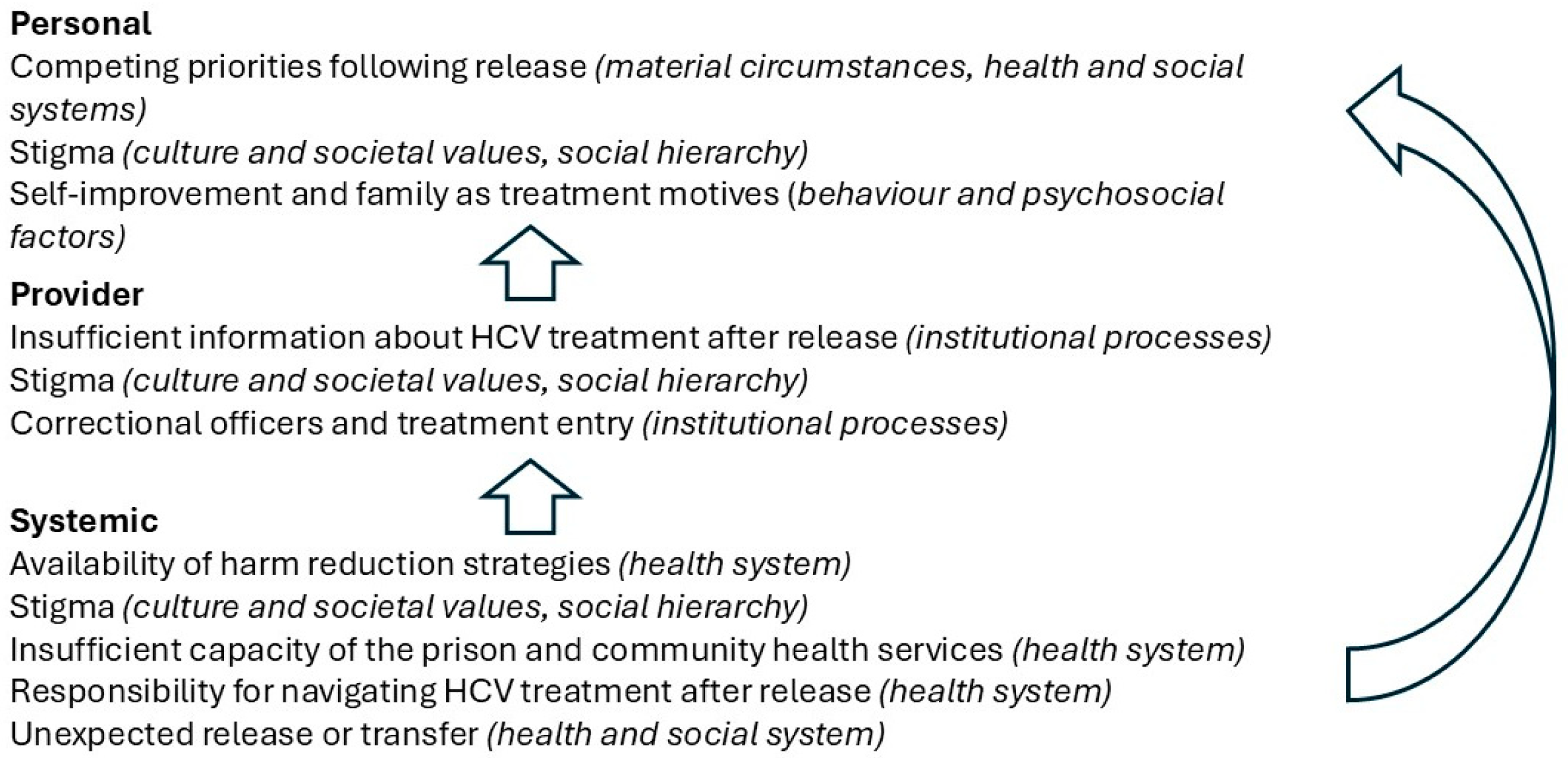

3. Results

3.1. Personal Factors

3.1.1. Competing Priorities After Release

- C5 (Male):

- Ever since getting out, things have been hectic. Trying to get in… living in this society, when you’re… when everything… you’re in a routine society. Everything’s busy here. You’ve got kids going to school. You’ve got jobs to do. It’s hectic.

- C2 (Male):

- I was worried about when I was getting out, I was worried about going to Centrelink, fixing up my shit, signing up my Job Network, finishing that shit. Go to probation and sign in…

3.1.2. Stigma

- C3 (male):

- Yeah, I’ve been judged for going in jail before, yeah. For sure. [I’ve been judged in] all types of ways, all types of ways. Jobs, job interviews, and just going to interviews, and that. They just sit [you] down after and [they’re] ticking all the boxes, and bang, [they get to] the next three questions, you know? [Do] you have a criminal record, [have] you been in jail? And do you use drugs? And I say yes to all of them. And then they tell you you’re going to get a phone call that night, and that phone call never comes… (laughs) Never comes. Yeah.

- C5 (male):

- Family doesn’t know. I haven’t told anybody. It’s just something that… Why worry them? Or why put the stigma on them? Because it is a contagious disease.

- S3:

- I think that some people might have such a deep shame that can contribute to not actually accessing treatment and supports. You know, the common thing I hear from people is “I don’t want to waste taxpayers’ money, I don’t want to take that sort of cost off the government” … we have to really reiterate that they are a human being who deserves treatment just like anybody else.

- C7 (female):

- … And [my ex-partner] just told me that his mum told him that I had the hepatitis C, that she wouldn’t let him use the shower at my place or eat at my place…

- C5 (male):

- … it’s good to know I’m not alone. I wasn’t alone… It was good talking to them anyway, because it helped. It was just good…to talk to other people with the same issue. That you’re not alone. You’re not ostracised… I had a friend that went through treatment. The one that told me in jail to get my blood test and just be tested. I talk to him about it a little bit, because he went through the [same] program. And we still see each other out here. So he’s probably the only person, other than you guys, that are aware of it.

- C6 (male):

- My dad and family have given me a lot of support… My parents know. But other than that, no one really…I don’t really explain [my HCV] to many other people except for family, except [some family members] that don’t [give me support] … because some of my family can be uptight.

3.1.3. Self-Improvement and Family as Treatment Motives

- C7 (Female):

- Because, I guess [acquiring HCV] was the consequence of bad choices and I had the ability to now… To potentially turn that outcome into a better outcome for a bad choice. I had a second chance, I guess.

- C2 (Male):

- [Treating HCV is important to me] ’cause I’ve got sisters at home. Little sisters, and my two little nieces …. And I cut myself shaving sometimes, and I don’t want to leave blood around and then they get Hep C. Know what I mean? That’s what I worry about. But I keep the blood away from them. Like, I tell them to just stay away from me…

- C7 (Female):

- Oh, I know I don’t have [cirrhosis] now. But I worry about finding out I have cirrhosis of the liver or whatever, or not seeing my kids. So I guess one issue heightens the other issue. Because I don’t have my kids, so that heightens the thought of, “Oh my God, what if I get cirrhosis of the liver and die, and I haven’t seen my kids?” So to get treated again, it’s a real blessing in disguise for me. Because now I cannot think in that manner.

3.2. Provider-Level Factors

3.2.1. Stigma

- S2:

- [They will experience] stigma. Even non-prisoners. I hear very regularly how a GP has treated them. Once they’ve found out that they’ve got a positive result for [HCV], and being accused of being a drug user when they’ve never used.

- C6 (male):

- To be honest, [health staff in prison facilities] don’t help you very much… They don’t really give you [any support]… I think that they would [treat me poorly], but more like I didn’t push myself to speak with them, in a way. I tried to keep myself segregated from them…

3.2.2. Insufficient Information About HCV Treatment After Release

- C4 (female):

- Well they could let, let girls know like where to go or where to start. ’Cause that’s part of the problem, like they tell us to go do all these things but we don’t know how… basically they said, “Oh, well you’re getting out soon so you can deal with it when you’re out”.

- C7 (Female):

- I didn’t really think much about [reinfection]. [Failing treatment] was a bit disappointing at first, but… yeah. I didn’t really think much more of it. I didn’t know that I could get a second one until… I think it was [the prison nurse practitioner] called me up this time… I was just going to live with it… it is what it is.

3.2.3. Nurse Practitioner S100 Prescribing

- S1:

- …It’s been, it’s probably one of the only real prohibitive factors in getting people into treatment sooner now, in the prisons… The main prohibitive factor is that s100 script. So, you know, [the nurse practitioner is] writing up all the scripts but [they] have to wait, usually one day a fortnight for the [senior medical officer] to then sign off on those and then send a pharmacy. So we’re losing at a minimum two weeks… [If nurse practitioners] had the right to prescribe DAAs in correctional facilities], [they] would able to script people daily like [they are able to] do in the community. … [they could] do all those scripts for those people that day, take them to the pharmacy the same day, if not the next day. So our pharmacy would be processing scripts for these people on a daily basis rather than fortnightly, or sometimes longer, basis.

- S4:

- … [The West Moreton Nurse Practitioner] has worked up over 700–800 patients in the time that we’ve commenced that telementoring and he’s increased his knowledge from, you know, nothing to now being able to treat the cirrhotics and re-treatments, and really being quite experienced in Hep C… He just needs to be able to write a script.

- S6:

- S100 prescribing it seems a bit silly. ’Cause, I mean, the thing is, for HIV and Hep B, I can see it, I can completely understand, they’re complicated diseases to treat with a whole raft of different medications …have complicated side effects. And they’re also chronic diseases that need chronic treatment, they’re not a short 3 month treatment that end up in a cure…It’s just ridiculous [that nurse practitioners can’t prescribe DAAs in prison], isn’t it?

3.2.4. Correctional Officers

- C2 (Male):

- It was frustrating me really bad. It was annoying me. I always have to get [the correctional officers] to call up medical and ask what’s going on. “Nah we’ll come and speak to you tonight”. They come back in a couple months.

- S9:

- There are definitely people who don’t agree with [the HCV treatment program]. Corrections is an even harder sell. Trying to convince correctional officers that HCV treatment is a good thing… Correctional staff are probably not very tactful at [hiding] their disdain that… all this money is being spent on “these people”, but if the [people living in prison] hear that, I guess it impacts them. Whether it be shame, or that feeling of obstruction.

3.3. Systemic Factors

3.3.1. Harm Reduction Strategies

- C3 (male):

- I don’t know, maybe, if I’m shooting up or something [post-release], and people that shoot up that don’t have Hep C, or maybe been in jail or something… they want to use your needle after you or something like that, well… you just decide to let [them know], as an honest person—“I’ve got Hep C”… then people look at you, “nah nah nah”. … but the people who have been in jail, I know, they quickly just take it out of your hands…

- S4:

- Some of the prisoners don’t want to come for their final [post treatment blood test in the community] because they know that they’ve injected and probably re-infected themselves. … [we are trying to communicate that] we have no stigma or discrimination against this… we will treat you as many times as you need to be re-treated.

- S1:

- …There’s a lot of women in there who are saying to me, “no, I don’t want to treat my Hepatitis C, what’s the point, I’m still using every day, I will not go on Hepatitis C treatment until you guys put me onto [opioid agonist treatment]”.

3.3.2. Insufficient Capacity of the Prison and Community Health Services

- C2 (Male):

- There’s not many nurses or doctors there…there’s like two nurses and two doctors there. And there’s like, the jail’s like all doubled on [over capacity].

- S2:

- [HCV] was always treated in the specialty areas, so GPs have not been experienced to do it. We sent a survey out to, um, the GPs that we’ve been working with… We provided education. I’ve dropped education packs to all the GPs, and they’ve told us that they’re not confident to treat even with the education.

- C2 (Male):

- It was all fuckery, and they were fucking me around. Like, making me go [to the prison health service] after every four months or so. It was taking that long, like, to tell me, actually, if I got it or not. They kept stuffing me around. I didn’t know what’s going on [at any point]… I thought in my head “What’s going on?”…. Like, I got my Hep C test done, but I don’t even know—I don’t know if I’ve got it, or not. It’s been fucking, a couple months that I got tested—am I clean or not?

- S1:

- … you’ve got a lag time between two to four weeks after that for medications to arrive at the jails to start treatment. So, hence why if someone’s going to be [released] in less than a month, and if I haven’t seen them yet, then it’s pretty much no chance of us giving them treatment…

- C5 (Male):

- Yeah, I’d see the nurse practitioner twice, maybe, in prison. And after treatment started, I didn’t see him again. And I wasn’t going to talk to the prison staff about it, because it was pointless… They’d just say, “We’ll put your name down, and see someone”, and it never happens… You’ve got to push constantly. (Interviewer: What [do you think] is the reason why it wouldn’t happen?) C5 (Male): Whether they’re too busy. Whether they just don’t give a shit… It’s like that for everyone… You’ve just got to keep pestering and pestering. … It gets pathetic at times, the wait. Again, [there] could just be so many people.

3.3.3. Responsibility for Navigating HCV Treatment After Release

- C13 (Male):

- If you guys aren’t coming to help us, that whenever I’m released… if you guys don’t touch base with us after we get our lives back, we’ll just, we’ll just have [HCV] forever. Because there’s no way to get rid of it without the pills.

- S4:

- … [Making appointments for HCV treatment is] generally not [the patient’s] priority once someone’s released from here. Making it so it’s up to them to phone us, you know, that’s a barrier in itself… It’s all up to them to push and make this happen.

- S1:

- … Often, [people recently released from incarceration] don’t necessarily know who to go to get a script, or they still think they might need to go to a liver specialist when you can just get a script from a GP now.

3.3.4. Unexpected Release or Transfer

- S1:

- … Quite often we get people who were waiting for medications to be dispensed, and they’ve suddenly been released. Some court order parole or something and they’ve been released, so then the man’s medication will sometimes be sent to the prison and they’ve already gone…that’s a lost opportunity for that patient… [Some prison facilities] can be very, very low [in the proportion of patients completing treatment], because [the patients are] just constantly going to court, getting released, or getting transferred and you’re losing touch with them.

- S4:

- We often don’t know when prisoners are getting out, so when we go and do their next appointment, that’s when we find out they’re getting out. We have tried to overcome that by talking to the prisoner about when they think they might be getting out, and do they have an address that [they] give us consent to finding them so that we can continue to get them engaged in care. But that doesn’t always work. Corrections [are] very difficult, they will not give me any contact details for patients once they’re released.… so I’m sort of at the mercy of the patient getting in contact with us and giving us updated contact details.

4. Discussion

4.1. Person-Level Factors

4.2. Provider-Level Factors

4.3. System-Level Factors

4.3.1. Limitations

4.3.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maucort-Boulch, D.; de Martel, C.; Franceschi, S.; Plummer, M. Fraction and incidence of liver cancer attributable to hepatitis B and C viruses worldwide: Liver cancer attributable to hepatitis viruses worldwide. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 2471–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016–2021: Towards Ending Viral Hepatitis; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Waheed, Y.; Siddiq, M.; Jamil, Z.; Najmi, M.H. Hepatitis elimination by 2030: Progress and challenges. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 4959–4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Fifth National Hepatitis C Strategy 2018–2022; Department of Health and Ageing, Ed.; Australian Government Canberra: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Hernandez-Con, P.; Wilson, D.L.; Tang, H.; Unigwe, I.; Riaz, M.; Ourhaan, N.; Jiang, X.; Song, H.J.; Joseph, A.; Henry, L.; et al. Hepatitis C Cascade of Care in the Direct-Acting Antivirals Era: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2023, 65, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bah, R.; Sheehan, Y.; Li, X.; Dore, G.J.; Grebely, J.; Lloyd, A.R.; Hajarizadeh, B.; Lloyd, A.; Hajarizadeh, B.; Sheehan, Y.; et al. Prevalence of blood-borne virus infections and uptake of hepatitis C testing and treatment in Australian prisons: The AusHep study. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 2024, 53, 101240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberg, N.; Daniels, J.; Crum, M.; Perkins, T.; Richie, B.E. Coming home from jail: The social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 45, 1084. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, S.R.; Fox, P.; Cabatingan, H.; Jaros, A.; Gorton, C.; Lewis, R.; Priscott, E.; Dore, G.J.; Russell, D.B. Demonstration of near-elimination of Hepatitis C virus among a prison population: The Lotus Glen Correctional Centre Hepatitis C Treatment Project. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwo, P.Y.; Poordad, F.; Asatryan, A.; Wang, S.; Wyles, D.L.; Hassanein, T.; Felizarta, F.; Sulkowski, M.S.; Gane, E.; Maliakkal, B.; et al. Glecaprevir and pibrentasvir yield high response rates in patients with HCV genotype 1–6 without cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaluca, T.; McDonald, L.; Craigie, A.; Gibson, A.; Desmond, P.; Wong, D.; Winter, R.; Scott, N.; Howell, J.; Doyle, J.; et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C in prisoners using a nurse-led, state-wide model of care. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawks, L.; Norton, B.L.; Cunningham, C.O.; Fox, A.D. The Hepatitis C virus treatment cascade at an urban postincarceration transitions clinic. J. Viral Hepat. 2016, 23, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, L.; Treloar, C.; Chambers, G.; Butler, T.; Guthrie, J. Contextualising the social capital of Australian Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal men in prison. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 167, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafferty, L.; Rance, J.; Grebely, J.; Lloyd, A.; Dore, G.J.; Treloar, C. Understanding facilitators and barriers of direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus infection in prison. J. Viral Hepat. 2018, 25, 1526–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, M.; Rhodes, T.; Martin, A. Taming systems to create enabling environments for HCV treatment: Negotiating trust in the drug and alcohol setting. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 83, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafferty, L.; Wild, T.C.; Rance, J.; Treloar, C. A policy analysis exploring hepatitis C risk, prevention, testing, treatment and reinfection within Australia’s prisons. Harm Reduct. J. 2018, 15, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, R.; Fraser, S.; Booker, N.; Treloar, C. Authenticity and Diversity: Enhancing Australian Hepatitis C Prevention Messages. Contemp. Drug Probl. 2013, 40, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, M.; Foster, M.; Bland, R. How the prison-to-community transition risk environment influences the experience of men with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Criminol. 2017, 50, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.C.; Cossar, R.D.; Wilkinson, A.L.; Quinn, B.; Dietze, P.; Walker, S.; Butler, T.; Curtis, M.; Aitken, C.; Kirwan, A.; et al. The Prison and Transition Health (PATH) cohort study: Prevalence of health, social, and crime characteristics after release from prison for men reporting a history of injecting drug use in Victoria, Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 227, 108970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffman, E. Stigma; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Nyblade, L.C. Measuring HIV stigma: Existing knowledge and gaps. Psychol. Health Med. 2006, 11, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Chaudoir, S.R. From Conceptualizing to Measuring HIV Stigma: A Review of HIV Stigma Mechanism Measures. AIDS Behav. 2009, 13, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broady, T.; Brener, L.; Hopwood, M.; Cama, E.; Treloar, C. Stigma Indicators Monitoring Project: Summary Report; Phase Two; UNSW Centre for Social Research in Health: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehmer, C.E.; Qin, S.; Young, B.C.; Strauser, D.R. Self-stigma of incarceration and its impact on health and community integration. Crim Behav Ment Health 2024, 34, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafferty, L.; Treloar, C.; Rance, J. Behind closed doors, no one sees, no one knows’: Hepatitis C, stigma and treatment-as-prevention in prison. Crit. Public Health 2018, 30, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeever, A.; O’Donovan, D.; Kee, F. Factors influencing compliance with Hepatitis C treatment in patients transitioning from prison to community—A summary scoping review. J. Viral. Hepat. 2023, 30, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanes-Lane, M.; Dussault, C.; Linthwaite, B.; Cox, J.; Klein, M.B.; Sebastiani, G.; Lebouché, B.; Kronfli, N. Using the barriers and facilitators to linkage to HIV care to inform hepatitis C virus (HCV) linkage to care strategies for people released from prison: Findings from a systematic review. J. Viral. Hepat. 2020, 27, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, T. The ‘risk environment’: A framework for understanding and reducing drug-related harm. Int. J. Drug Policy 2002, 13, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health; World Health Organization, Ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, L.; Selvey, L.; Williams, O.; Gilks, C.; Smirnov, A. Reasons for Not Seeking Hepatitis C Treatment among People Who Inject Drugs. Subst. Use Misuse 2020, 56, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo; Q.I.P. Ltd., Ed.; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Burlington, VT, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Winter, R.; Young, J.T.; Stoové, M.; Agius, P.A.; Hellard, M.E.; Kinner, S.A. Resumption of injecting drug use following release from prison in Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016, 168, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaluca, T.; Craigie, A.; McDonald, L.; Edwards, A.; Winter, R.; Hoang, A.; Pappas, A.; Waldron, A.; McCoy, K.; Stoove, M.; et al. Care Navigation Increases Initiation of Hepatitis C Treatment After Release From Prison in a Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial: The C-LINK Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, R.J.; Sheehan, Y.; Papaluca, T.; Macdonald, G.A.; Rowland, J.; Colman, A.; Stoove, M.; Lloyd, A.R.; Thompson, A.J. Consensus recommendations on the management of hepatitis C in Australia’s prisons. Med. J. Aust. 2023, 218, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, R.J.; Holmes, J.A.; Papaluca, T.J.; Thompson, A.J. The Importance of Prisons in Achieving Hepatitis C Elimination: Insights from the Australian Experience. Viruses 2022, 14, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, Z.; Al-Kurdi, D.; Nelson, M.; Shimakawa, Y.; Selvapatt, N.; Lacey, J.; Thursz, M.R.; Lemoine, M.; Brown, A.S. Time matters: Point of care screening and streamlined linkage to care dramatically improves hepatitis C treatment uptake in prisoners in England. Int. J. Drug Policy 2020, 75, 102608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surey, J.; Menezes, D.; Francis, M.; Gibbons, J.; Sultan, B.; Miah, A.; Abubakar, I.; Story, A. From peer-based to peer-led: Redefining the role of peers across the hepatitis C care pathway: HepCare Europe. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74 (Suppl. S5), v17–v23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, D.; Murtagh, R.; Cullen, W.; Keevans, M.; Laird, E.; McHugh, T.; McKiernan, S.; Miggin, S.J.; O’Connor, E.; O’Reilly, D.; et al. Evaluating peer-supported screening as a hepatitis C case-finding model in prisoners.(Report). Harm Reduct. J. 2019, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, K.; Sedillo, M.L.; Kalishman, S.; Page, K.; Arora, S. The New Mexico Peer Education Project: Filling a Critical Gap in HCV Prison Education. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2018, 29, 1544–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutterheim, S.E.; Pryor, J.B.; Bos, A.E.R.; Hoogendijk, R.; Muris, P.; Schaalma, H.P. HIV-related stigma and psychological distress: The harmful effects of specific stigma manifestations in various social settings. AIDS 2009, 23, 2353–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treloar, C.; Jackson, L.C.; Gray, R.; Newland, J.; Wilson, H.; Saunders, V.; Johnson, P.; Brener, L. Multiple stigmas, shame and historical trauma compound the experience of Aboriginal Australians living with hepatitis C. Health Sociol. Rev. 2016, 25, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puljevic, C.; Massi, L.; Brown, R.; Mills, R.; Turner, L.; Smirnov, A.; Selvey, L.A. Barriers and enablers to hepatitis C treatment among clients of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services in South East Queensland, Australia: A qualitative enquiry. Aust. J. Prim Health 2022, 28, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treloar, C.; Jackson, C.; Gray, R.; Newland, J.; Wilson, H.; Saunders, V.; Johnson, P.; Brener, L. Care and treatment of hepatitis C among Aboriginal people in New South Wales, Australia: Implications for the implementation of new treatments. Ethn. Health 2016, 21, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batchelder, A.W.; Heo, M.; Foley, J.D.; Sullivan, M.C.; Lum, P.; Pericot Valverde, I.; Taylor, L.E.; Mehta, S.H.; Kim, A.Y.; Norton, B.; et al. Shame and stigma in association with the HCV cascade to cure among people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend 2023, 253, 111013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, R.; Aggleton, P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilson, L. Trust and the development of health care as a social institution. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 1453–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overton, K.; Clegg, J.; Pekin, F.; Wood, J.; McGrath, C.; Lloyd, A.; Post, J.J. Outcomes of a nurse-led model of care for hepatitis C assessment and treatment with direct-acting antivirals in the custodial setting. Int. J. Drug Policy 2019, 72, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacIsaac, M.B.; Papaluca, T.; McDonald, L.; Craigie, A.; Edwards, A.; Layton, C.; Gibson, A.; Winter, R.J.; Iyer, K.; Sim, A.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes of a Decentralized, Nurse-Led, Statewide Model of Care for Hepatitis C Among People in Prison in Victoria, Australia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 1, ciae471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zickmund, S.; Ho, E.Y.; Masuda, M.; Ippolito, L.; LaBrecque, D.R. “They treated me like a leper”. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2003, 18, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, J.M.; Elafros, M.A.; Logie, C.H.; Banik, S.; Turan, B.; Crockett, K.B.; Pescosolido, B.; Murray, S.M. Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harney, B.L.; Korchinski, M.; Young, P.; Scow, M.; Jack, K.; Linsley, P.; Bodkin, C.; Brothers, T.D.; Curtis, M.; Higgs, P.; et al. It is time for us all to embrace person-centred language for people in prison and people who were formerly in prison. Int. J. Drug Policy 2022, 99, 103455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronfli, N.; Mambro, A.; Riback, L.R.; Ortiz-Paredes, D.; Dussault, C.; Chalifoux, S.; del Balso, L.; Petropoulos, A.; Lim, M.; Halavrezos, A.; et al. Perceived patient navigator services and characteristics to address barriers to linkage to hepatitis C care among people released from provincial prison in Quebec, Canada. Int. J. Drug Policy 2024, 133, 104624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffa, C.; Mackay, A. Hyperincarceration and human rights abuses of First Nations children in juvenile detention in Queensland and the Northern Territory. Curr. Issues Crim. Justice 2024, 37, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, A.; Higgs, P.; Carruthers, S. Aboriginal people with chronic HCV: The role of community health nurses for improving health-related quality of life. Collegian 2020, 27, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queensland Mental Health Commission. Don’t Judge, and Listen: Experiences of Stigma and Discrimination Related to Problematic Alcohol and Other Drug Use; Queensland Mental Health Commission: Brisbane, Australia, 2020.

- Walker, S.; Seear, K.; Higgs, P.; Stoové, M.; Wilson, M. “A spray bottle and a lollipop stick”: An examination of policy prohibiting sterile injecting equipment in prison and effects on young men with injecting drug use histories. Int. J. Drug Policy 2020, 80, 102532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treloar, C.; McCredie, L.; Lloyd, A.R. The prison economy of needles and syringes: What opportunities exist for blood borne virus risk reduction when prices are so high? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.K.; Hickman, M.; Spaulding, A.C.; Vickerman, P. Prisons Can Also Improve Drug User Health in the Community; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; Volume 115, pp. 914–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.; Martin, N.K.; Hickman, M.; Hutchinson, S.J.; Aspinall, E.; Taylor, A.; Munro, A.; Dunleavy, K.; Peters, E.; Bramley, P.; et al. Modelling the impact of incarceration and prison-based hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment on HCV transmission among people who inject drugs in Scotland. Addiction 2017, 112, 1302–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, J.D.P.; McKenzie, M.M.P.H.; Larney, S.P.; Wong, J.B.M.D.; Tran, L.M.S.; Clarke, J.M.D.; Noska, A.M.D.; Reddy, M.B.A.; Zaller, N.P. Methadone continuation versus forced withdrawal on incarceration in a combined US prison and jail: A randomised, open-label trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafferty, L.; Rance, J.; Grebely, J.; Dore, G.J.; Lloyd, A.R.; Treloar, C. Perceptions and concerns of hepatitis C reinfection following prison-wide treatment scale-up: Counterpublic health amid hepatitis C treatment as prevention efforts in the prison setting. Int. J. Drug Policy 2020, 77, 102693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larney, S.; Dolan, K. Increased access to opioid substitution treatment in prisons is needed to ensure equivalence of care. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2008, 32, 86–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queensland Corrective Services. Drug and Alcohol Strategy Action Plan 2020–2021; Queensland Government, Ed.; Queensland Corrective Services: Brisbane, Australia, 2020.

- UN General Assembly. A/RES/70/175; United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules). Resolution/Adopted by the General Assembly, Ed.; UN General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/legal/resolution/unga/2016/en/119111 (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Gibbs, L.; Kealy, M.; Willis, K.; Green, J.; Welch, N.; Daly, J. What have sampling and data collection got to do with good qualitative research? Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2007, 31, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, A.; Llerena, S.; Cobo, C.; Pallas, J.R.; Mateo, M.; Cabezas, J.; Fortea, J.I.; Alvarez, S.; Pellon, R.; Crespo, J.; et al. Microenvironment Eradication of Hepatitis C: A Novel Treatment Paradigm. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 1639–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grebely, J.; Applegate, T.L.; Cunningham, P.; Feld, J.J. Hepatitis C point-of-care diagnostics: In search of a single visit diagnosis. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2017, 17, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.J.; Dawson, O.; Sheehan, Y.; Shrestha, L.B.; Lloyd, A.R.; Sheehan, J.; Maduka, N.; Cabezas, J.; Kronfli, N.; Akiyama, M.J. Co-designing the INHSU Prisons Hepatitis C Advocacy Toolkit using the Advocacy Strategy Framework. Int. J. Drug Policy 2024, 134, 104628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, Y.; Lafferty, L.; Tedla, N.; Byrne, M.; Dawson, O.; Stewart, S.; Leber, B.; Habraken, N.; Lloyd, A.R. Development of an evidence-based hepatitis C education program to enhance public health literacy in the Australian prison sector: The Hepatitis in Prisons Education program (HepPEd). Int. J. Drug Policy 2024, 129, 104461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosak, J.; Drainoni, M.L.; Bryer, C.; Goodman, D.; Messersmith, L.; Declercq, E. ‘It opened my eyes, my ears, and my heart’: Codesigning a substance use disorder treatment programme. Health Expect 2024, 27, e13908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panahi, I.; Selvey, L.A.; Puljević, C.; Kvassay, A.; Grimstrup, D.; Smirnov, A. ‘You’ve Just Got to Keep Pestering’: Barriers and Enablers of Attaining Continuity of Hepatitis C Care for People Transitioning Between Prison and Community Health Services in South-East Queensland, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020238

Panahi I, Selvey LA, Puljević C, Kvassay A, Grimstrup D, Smirnov A. ‘You’ve Just Got to Keep Pestering’: Barriers and Enablers of Attaining Continuity of Hepatitis C Care for People Transitioning Between Prison and Community Health Services in South-East Queensland, Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(2):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020238

Chicago/Turabian StylePanahi, Idin, Linda A. Selvey, Cheneal Puljević, Amanda Kvassay, Dorrit Grimstrup, and Andrew Smirnov. 2025. "‘You’ve Just Got to Keep Pestering’: Barriers and Enablers of Attaining Continuity of Hepatitis C Care for People Transitioning Between Prison and Community Health Services in South-East Queensland, Australia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 2: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020238

APA StylePanahi, I., Selvey, L. A., Puljević, C., Kvassay, A., Grimstrup, D., & Smirnov, A. (2025). ‘You’ve Just Got to Keep Pestering’: Barriers and Enablers of Attaining Continuity of Hepatitis C Care for People Transitioning Between Prison and Community Health Services in South-East Queensland, Australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(2), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22020238