“Understand the Way We Walk Our Life”: Indigenous Patients’ Experiences and Recommendations for Healthcare in the United States

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Indigenous Research Methodology

2.2. Study Context

2.3. Data Collection

3. Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Participant Demographics

- The Healthcare Encounter

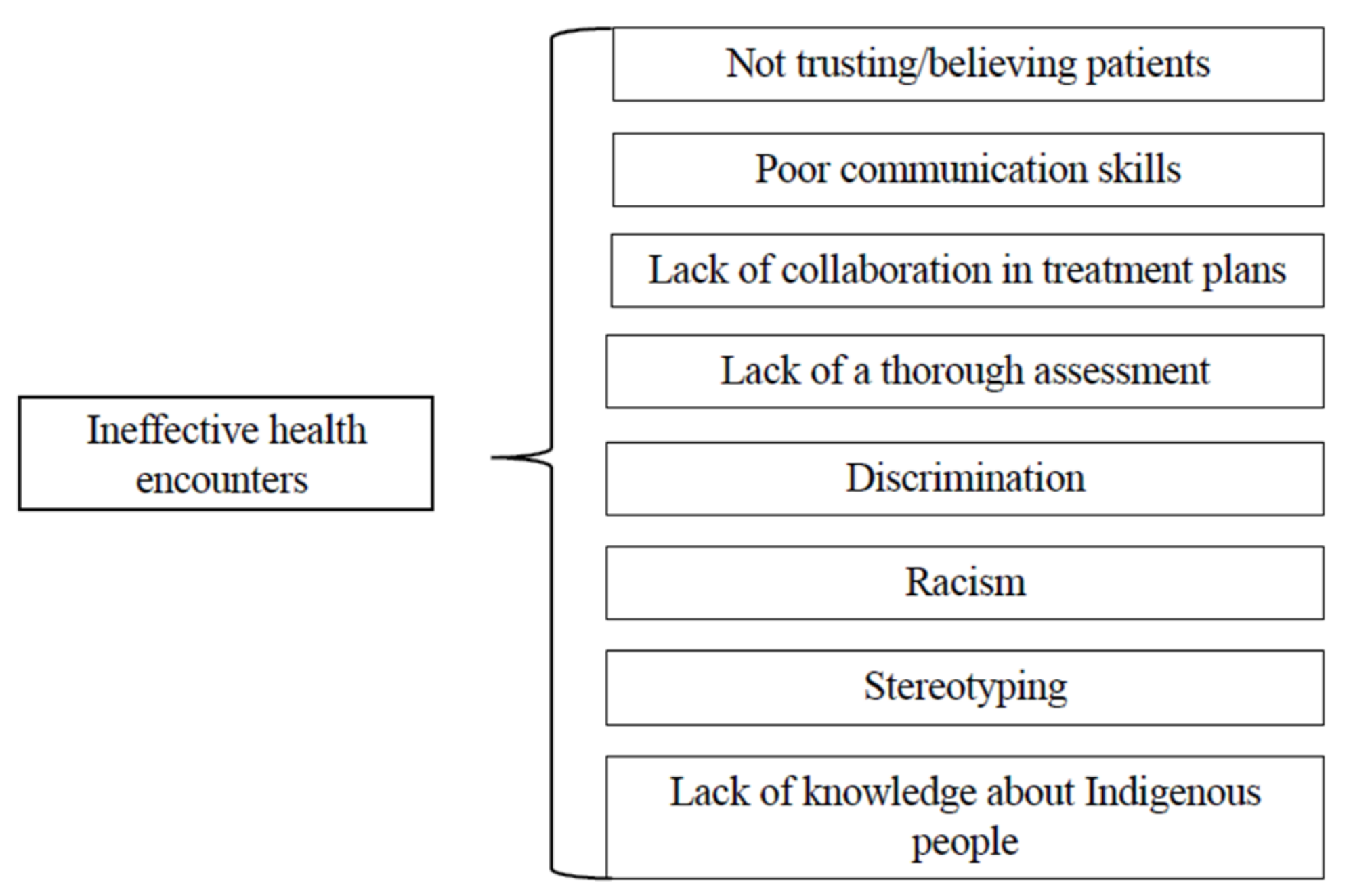

- Ineffective health encounters

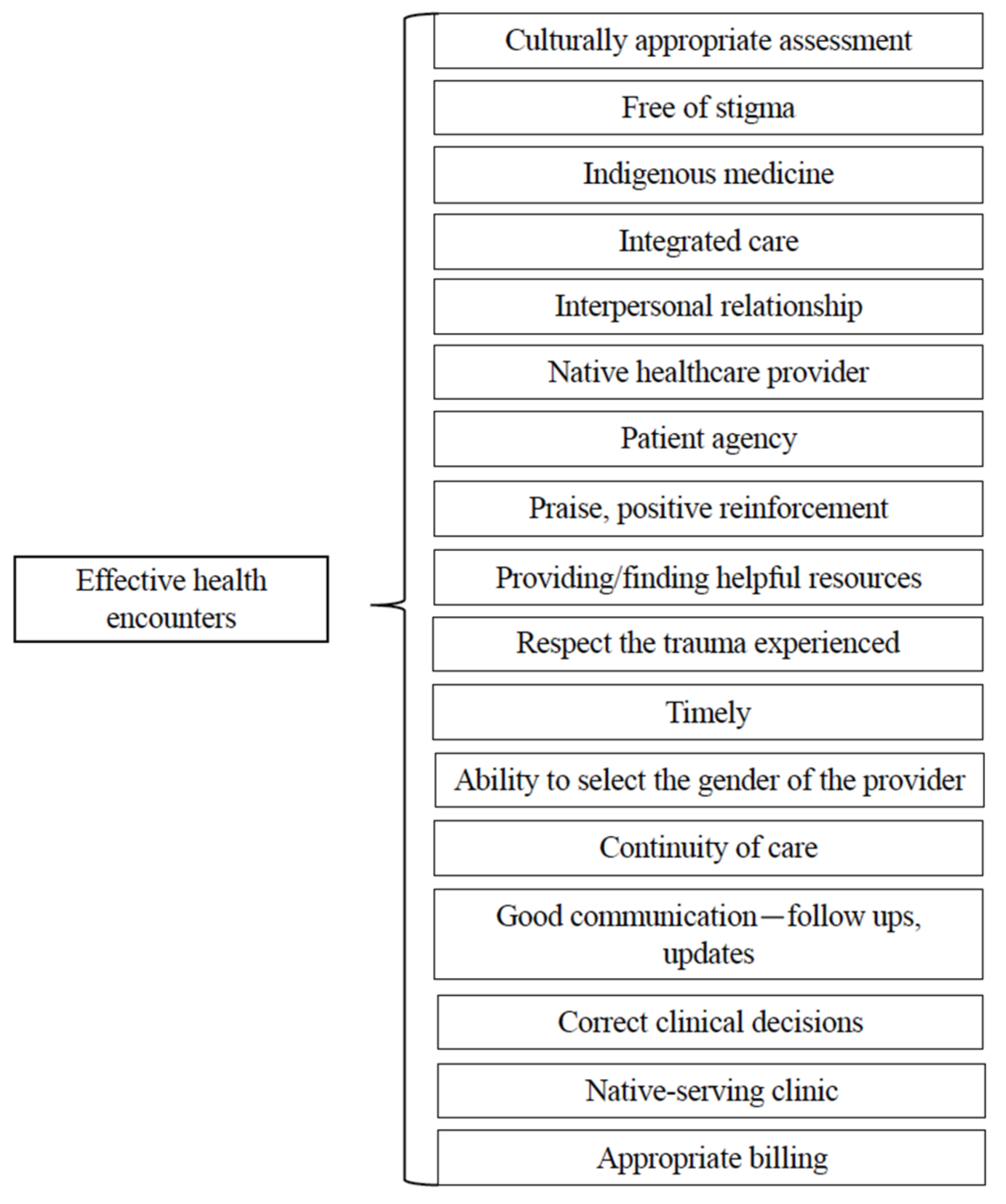

- Effective health encounters

- Improvements needed for healthcare encounters

- Healthcare Systems

- D.

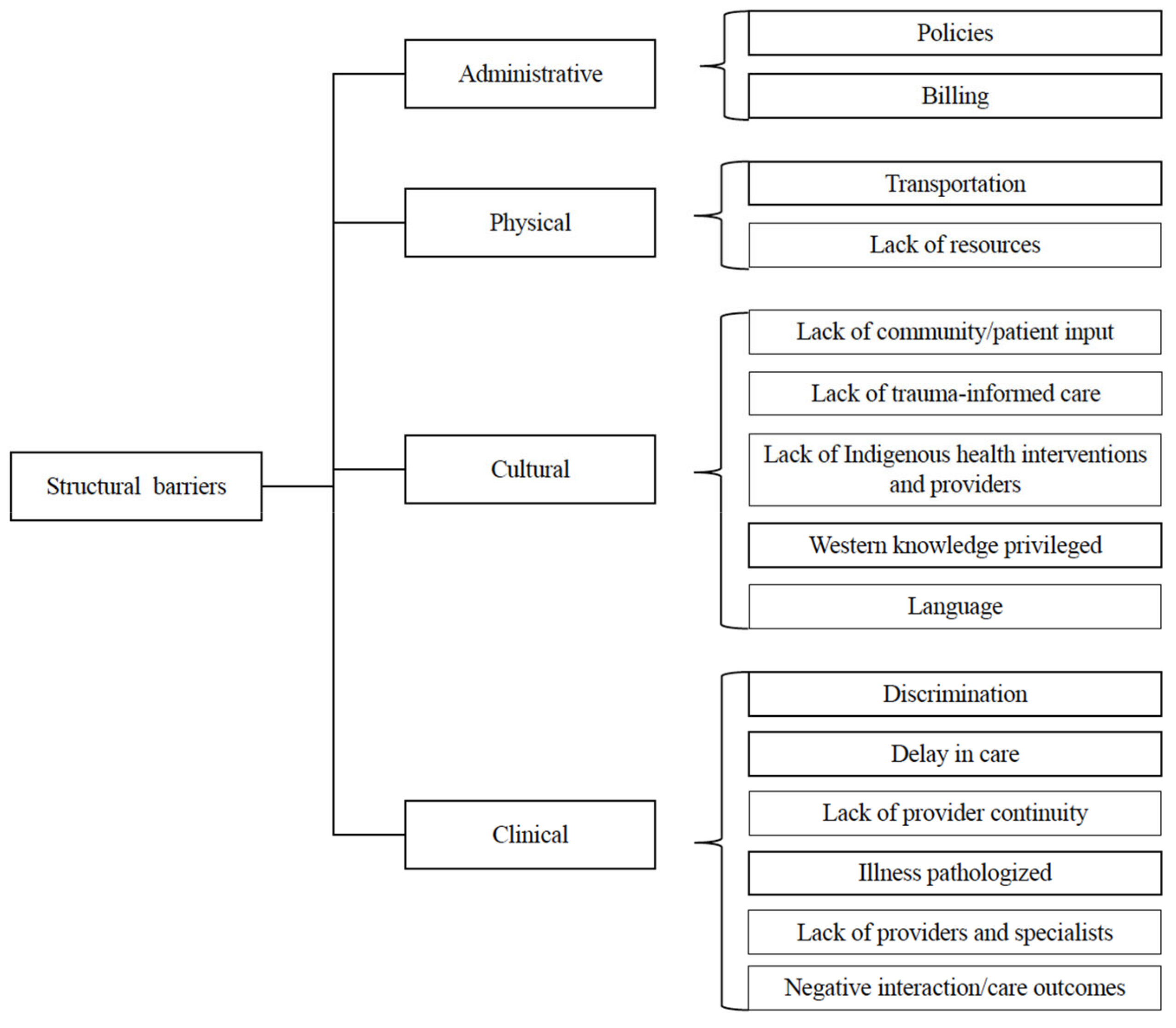

- Systemic and structural barriers

- E.

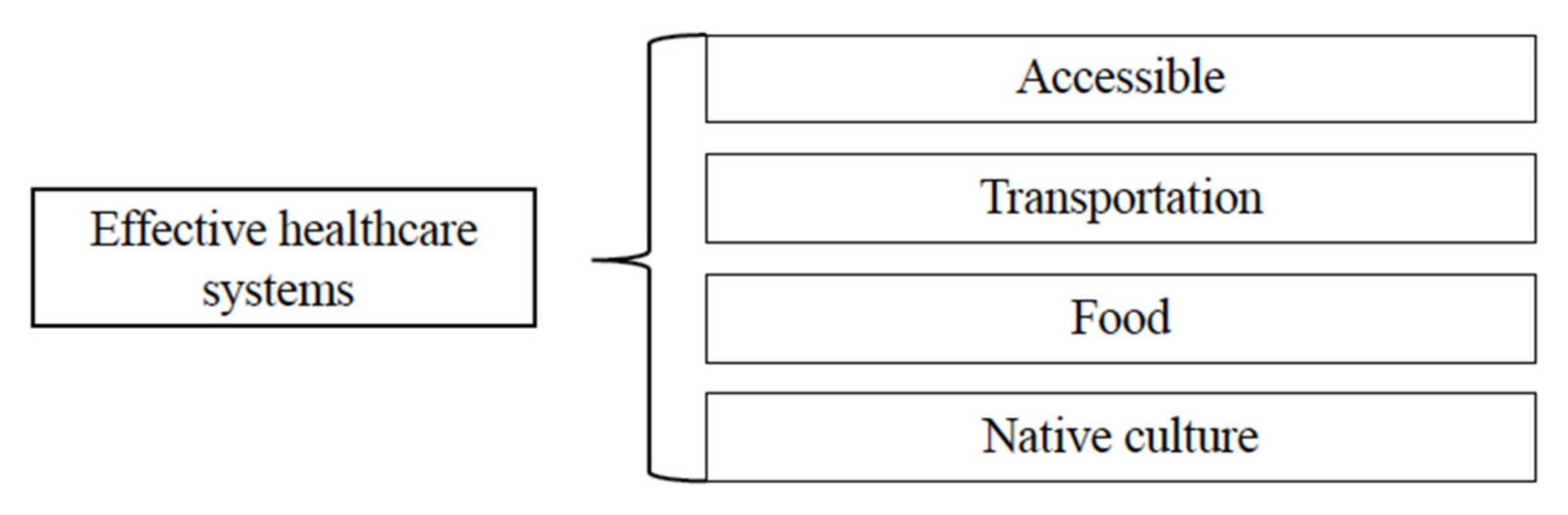

- Effective healthcare systems

- F.

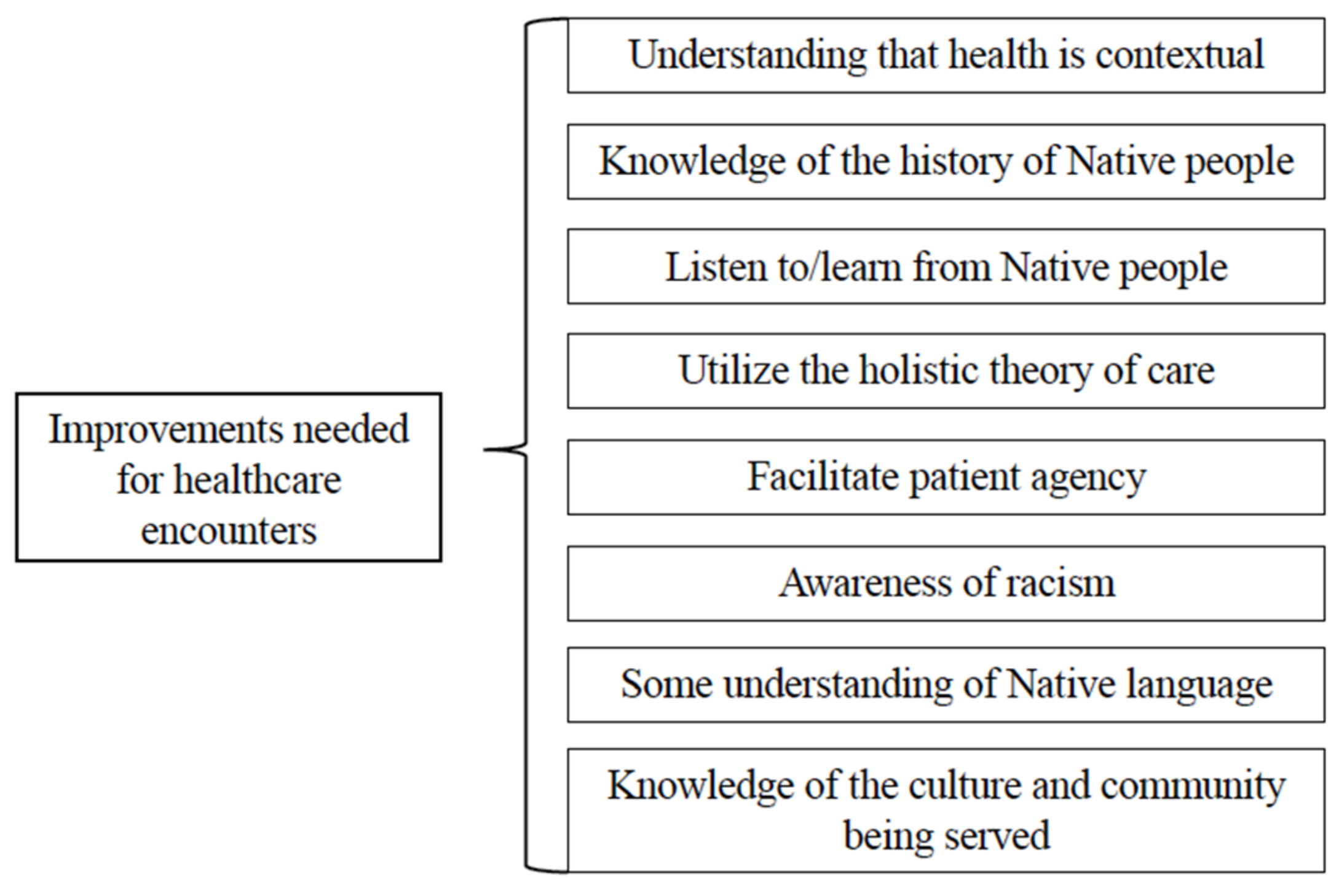

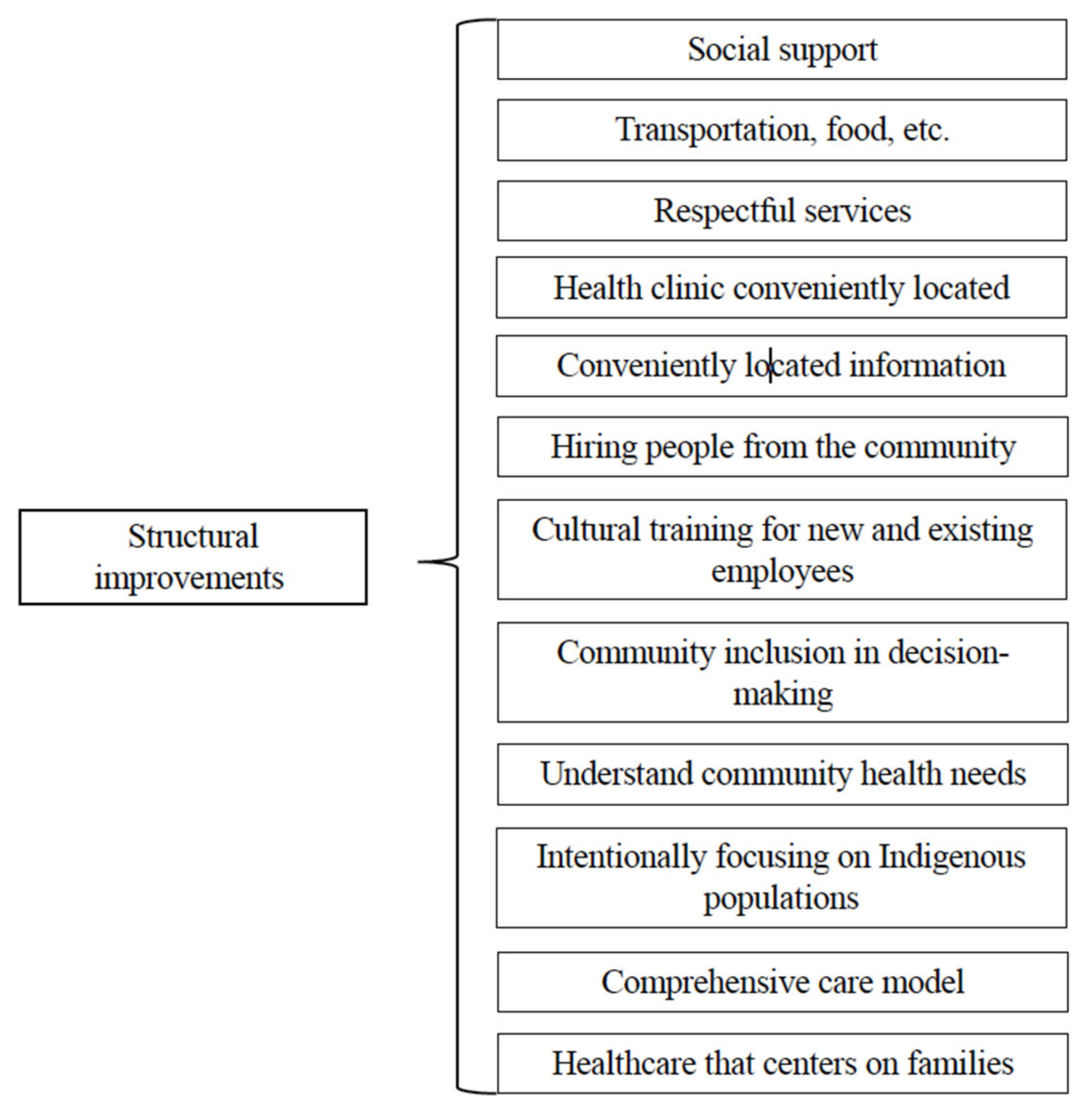

- Improvements needed for healthcare systems

- Indigenous Knowledge and Beliefs

4.2. The Healthcare Encounter

4.2.1. Ineffective Health Encounters

“… we’ve all had to deal (with) prejudice in one way or another, … I noticed that their body language is pretty obvious, and their tone of their voice is obvious that they’re not into seeing you…”

“I don’t feel I get treated fairly or get the same care as a non-Native would.”

“And when we were all growing up…in the textbooks, we read bad things about Natives. So that’s how they are raised in school—that Native people were bad…today that’s what is still in the books.”

“Each tribe has their own culture and history and language and all. I ran into that a lot of times where, you know, if you, you tell them you’re Indian and all they think is war bonnets and horses.”

“I’m still a person and I still need to be included on the treatment and, no, you can’t make all the decisions…”

“What I really disliked was that the doctor did not trust my mother’s intuition when it came to my child, and she pretty much dismissed what my thoughts and feelings were … and he went into a full-blown seizure after that. So, she (provider) was not hearing me. She just said that he was having fainting spells and I really sensed it was more than that, but she basically dismissed what I thought and that right there frustrates me…”

“It’s like when I kept having a bad headache here and the day I came, and they didn’t know I had a stroke.”

4.2.2. Effective Health Encounters

“I have a cut on my toe and she listened to my lungs and she listened to my heart and, you know, I never get out of there without getting the once over, which is nice. She knows what’s going on.”

“…(The provider) makes sure that I understand the medications they’re putting me on, and how to take them or what I’m using this medication for.”

4.2.3. Improvements Needed for Healthcare Encounters

“I come from a very Native background and we don’t really trust people and doctors; so, if they could somehow learn more about our different cultures and traditions and somehow make us feel more comfortable and like them.”

“…we have a hard time opening up. We’ve come from…histories with things that people tend to look down on. But to understand us is to know that those are a lot of times secondary symptoms [that are] deeper.”

“You know, if they’re in your neighborhood, they should know the people that they’re dealing with, you know, instead of coming from way out in the suburbs and then, you know, coming here and then looking at you like you’re less than… They should know and experience the culture that they’re dealing with.”

“A lot of times, the ones that are getting the care, their [Indigenous patients] feedback, their input, they [providers] never considered it…a bunch of people that write stuff in books that never even lived it make our decisions for us…”

4.3. Healthcare Systems

4.3.1. Structural Barriers

“We are the original people here at least on this continent; so, I would appreciate it if they would at least get to know our cultures and the background. They have special languages and interpreters for other people, why can’t they have the same thing.”

“I wish there was an option for that [traditional Indigenous medicine] instead of regular medicine. There’s just so many people hooked on stuff like opiates now because of that [Western medicine]. I wish they’d offer more traditional medicine you know, before they start pushing the pills on you.”

“…after he had read all my medical records, I went back for an appointment, and he actually apologized to me and told me that he could see that I had gotten very good care at the (Indigenous-serving healthcare center).”

“I took my son over there and I gave them my tribal card and they looked at me and said they would not see my son unless I had the cash or a credit card to hand them.”

4.3.2. Effective Healthcare Systems

“Just grateful to have (an Indigenous-serving clinic) here (in our community).”

“…I wanted to detox and then I saw the sign at the bus stop and it said to call. So, I came here and saw someone and they started treatment plan and changed my prescription that night… She (provider) acts, because she cares. She’s easy to talk to and you know I feel very satisfied and happy with the treatment plan. You know I was just another number at the other place. It’s great—they don’t treat me like a drug addict. And getting help and I see a counselor and see a therapist. I got to come here every day, but they got to arrange for me a cab every day and I’ve never had anyone offer to do that for me. I’ve never had anybody treat me that well. And they’re always feeding me, I mean they always have food here. I’m very satisfied with the treatment. With everybody, the therapist she’s always calling, it’s been great. I would recommend this to anybody. It’s great. I know they care about me.”

4.3.3. Improvements Needed for Healthcare Systems

“I think that’s really important to have community inclusiveness at the decision-making table because we receive the services.”

“I think they could have more resources to do their job better.”

4.4. Indigenous Knowledge and Beliefs

“As you can tell…we do use a lot of laughter to be more comfortable, that’s what we do at a lot of our ceremonies at home, we gather and have meals and joke and laugh with one another to get comfortable… and that’s where we get our community togetherness…”

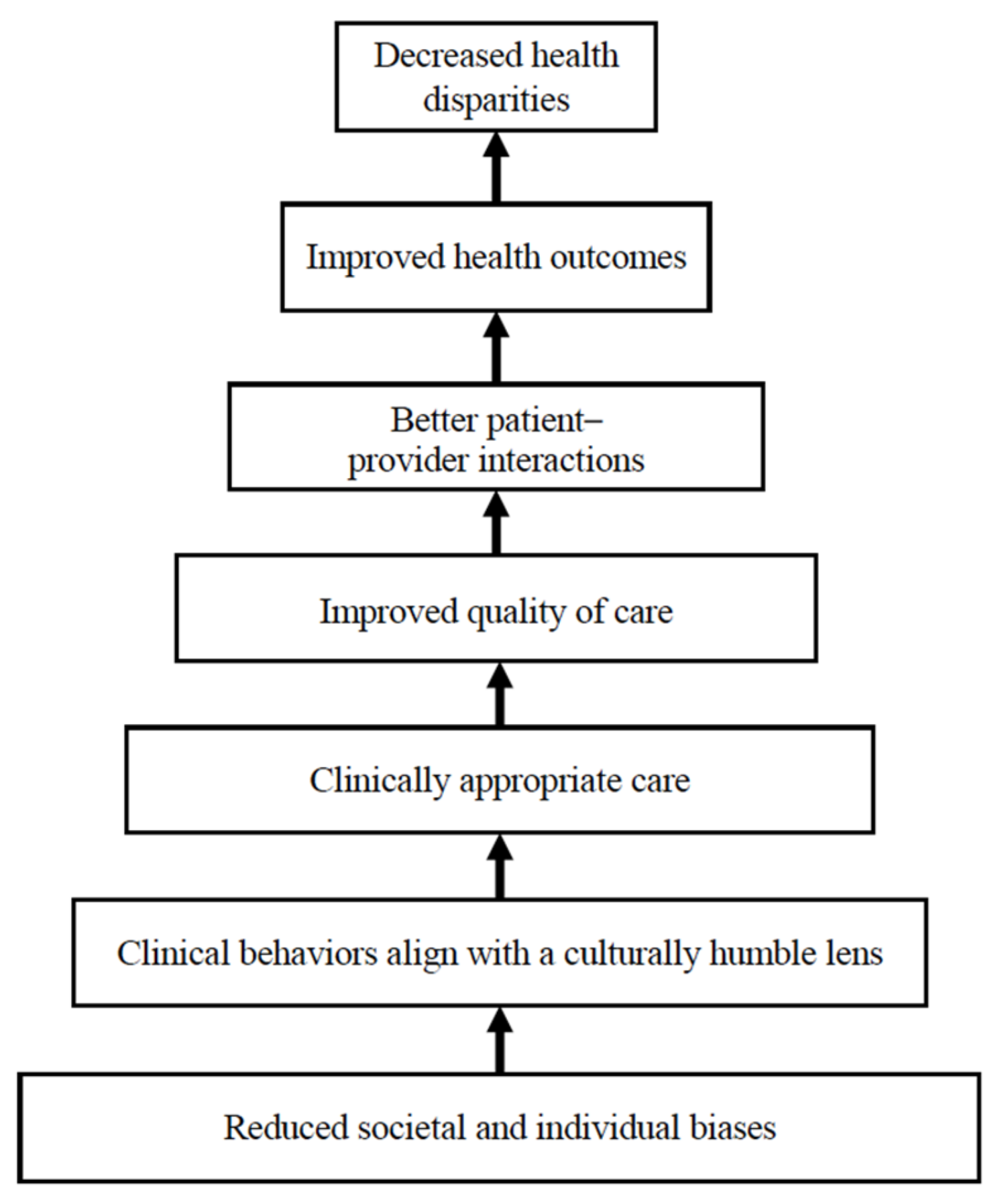

5. Discussion

5.1. Future Directions

5.2. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Focus Group Questions

| Question | Response Options |

| Introduction: We are working to create training for all healthcare providers at (clinic) to improve the care they deliver. We are particularly interested in discussing what is needed so that healthcare providers deliver culturally sensitive care to patients (What we are not discussing is how the clinic operates—issues related to wait times and contract health services issues, for example). | |

| Main Question: 1. What would you like to see as part of their training to meet this goal? | Open |

| Follow-up Questions 2. What would you like your healthcare providers to know about you, your family, and your culture to be able to treat you effectively? | Open |

| 3. Do you think your providers know enough about Native American people and culture? | 1. No. If no, what more do they need to know? 2. Yes. If yes, what things do they already know that have been helpful as they care for you? |

| 4. Do you wish your healthcare provider would treat you/your family differently? a. Do you think you are treated differently because you are Native American? b. Different cultural/racial communication? | 1. No. If no, what do you like about how your provider treats you? 2. Yes. If yes, how would you like to be treated? |

| 5. Do you get the healthcare you want? | 1. No. If no, what would you like to see more/less of? 2. Yes. If yes, what do you like about it? |

| Wrap-up Questions 6. Of all the topics that we discussed around your personal experiences of healthcare, what is the most important experience that came up for you? | Open |

| 7. Is there anything that we should have talked about but didn’t in regards to your healthcare experiences? | Open |

References

- Kirmayer, L.; Simpson, C.; Cargo, M. Healing traditions: Culture, community and mental health promotion with Canadian Aboriginal Peoples. Australas. Psychiatry 2003, 11 (Suppl. S1), S15–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R. The cultural erosion of Indigenous people in health care. CMAJ 2017, 189, E78–E79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, L.; McConkey, S.; Corrado, A.M. Colonial legacies and collaborative action: Improving Indigenous Peoples’ health care in Canada. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2019, 10, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, S.E.; Wilson, K. Understanding barriers to health care access through cultural safety and ethical space: Indigenous people’s experiences in Prince George, Canada. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 218, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.S.; Davey, R.; Mohanty, I.; Upton, P. “Everything is provided free, but they are still hesitant to access healthcare services”: Why does the indigenous community in Attapadi, Kerala continue to experience poor access to healthcare? Int. J. Equity Health 2020, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, I.; Robson, B.; Connolly, M.; Al-Yaman, F.; Bjertness, E.; King, A.; Tynan, M.; Madden, R.; Bang, A.; Coimbra, C.E., Jr.; et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (The Lancet-Lowitja Institute Global Collaboration): A population study. Lancet 2016, 388, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheson, K.; Seymour, A.; Landry, J.; Ventura, K.; Arsenault, E.; Anisman, H. Canada’s Colonial Genocide of Indigenous Peoples: A Review of the Psychosocial and Neurobiological Processes Linking Trauma and Intergenerational Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, T.G.A.; Starks, R.R.B.; Attakai, A.; Molina, F.; Cordova-Marks, F.; Kahn-John, M.; Antone, C.L.; Flores, M., Jr.; Garcia, F. The Generational Impact of Racism on Health: Voices from American Indian Communities. Health Aff. 2022, 41, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ‘Addressing Racism’ Investigation. In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-Specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care; Ministry of Health British Columbia: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://www.bcafn.ca/sites/default/files/docs/news/In-Plain-Sight-Summary-Report.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Harris, R.; Tobias, M.; Waldegrave, K.; Jeffreys, M.; Karlsen, S.; Nazroo, J. Effects of self-reported racial discrimination and deprivation on Māori health and inequalities in New Zealand: Cross-sectional study. Lancet 2006, 367, 2005–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findling, M.G.; Casey, L.S.; Fryberg, S.A.; Hafner, S.; Blendon, R.J.; Benson, J.M.; Sayde, J.M.; Miller, C. Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of Native Americans. Health Serv. Res. 2019, 54 (Suppl. S2), 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.; Gillies, M.; Howard, P.J.; Coffin, J. It’s enough to make you sick: The impact of racism on the health of Aboriginal Australians. Aust. N. Zeal. J. Public Health 2007, 31, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, J.T.; Brolan, C.E.; Hill, P.S. Aboriginal medical services cure more than illness: A qualitative study of how Indigenous services address the health impacts of discrimination in Brisbane communities. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisely, S.; Alichniewicz, K.K.; Black, E.B.; Siskind, D.; Spurling, G.; Toombs, M. The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in Indigenous people of the Americas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017, 84, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, A.Z.; Walker, R.J.; Campbell, J.A.; Davidson, T.M.; Egede, L.E. Telehealth and Indigenous populations around the world: A systematic review on current modalities for physical and mental health. Mhealth 2020, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Percentage of Coronary Heart Disease for Adults Aged 18 and Over, United States, 2019—2023; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/NHISDataQueryTool/SHS_adult/index.html (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Puumala, S.E.; Burgess, K.M.; Kharbanda, A.B.; Zook, H.G.; Castille, D.M.; Pickner, W.J.; Payne, N.R. The role of bias by emergency department providers in care for American Indian children. Med. Care 2016, 54, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitching, G.T.; Firestone, M.; Schei, B.; Wolfe, S.; Bourgeois, C.; O’Campo, P.; Rotondi, M.; Nisenbaum, R.; Maddox, R.; Smylie, J. Unmet health needs and discrimination by healthcare providers among an Indigenous population in Toronto, Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2020, 111, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.; Savage, V.; Kaufman, H. Assessing equitable care for Indigenous and Afrodescendant women in Latin America. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 2015, 38, 96–109. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, H.F. Ethnicity- and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: An integrative review and conceptual model. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, K.L.; Harding, A.K.; Lambert, W.E.; Fu, R.; Henderson, W.G. Perceived experiences of discrimination in health care: A barrier for cancer screening among American Indian women with type 2 diabetes. Women’s Health Issues 2013, 23, e61–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, L.; McConkey, S. Insiders’ insight: Discrimination against Indigenous Peoples through the eyes of health care professionals. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2018, 6, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLane, P.; Mackey, L.; Holroyd, B.R.; Fitzpatrick, K.; Healy, C.; Rittenbach, K.; Plume, T.B.; Bill, L.; Bird, A.; Healy, B.; et al. Impacts of racism on First Nations patients’ emergency care: Results of a thematic analysis of healthcare provider interviews in Alberta, Canada. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, A.; Fleming, K.; Markwick, N.; Morrison, T.; Lagimodiere, L.; Kerr, T. “They treated me like crap and I know it was because I was Native”: The healthcare experiences of Aboriginal peoples living in Vancouver’s inner city. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 178, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redvers, N.; Blondin, B. Traditional Indigenous medicine in North America: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkham, R.; Maple-Brown, L.J.; Freeman, N.; Beaton, B.; Lamilami, R.; Hausin, M.; Puruntatemeri, A.M.; Wood, P.; Signal, S.; Majoni, S.W.; et al. Incorporating Indigenous knowledge in health services: A consumer partnership framework. Public Health 2019, 176, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zestcott, C.A.; Spece, L.; McDermott, D.; Stone, J. Health care providers’ negative implicit attitudes and stereotypes of American Indians. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2021, 8, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shotton, H.J.; Tachine, A.R.; Nelson, C.A.; Minthorn, R.Z.T.H.A.; Waterman, S.J. Living our research through Indigenous scholar sisterhood practices. Qual. Inq. 2017, 24, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods; Fernwood Pub.: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, K.; Drew, N.; Nystrom, M. Reflective Lifeworld Research; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lieblich, A.; Tuval-Mashiach, R.; Zilber, T.B. Narrative Research: Reading, Analysis and Interpretation; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, A. Following the red thread of information in information literacy research: Recovering local knowledge through interview to the double. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2014, 36, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S. Issues of Validity in Qualitative Research; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- University of Huddersfield. What is Template Analysis; University of Huddersfield: Huddersfield, UK, 2021; Available online: https://research.hud.ac.uk/research-subjects/human-health/template-analysis/what-is-template-analysis/ (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Williams, D.R.; Lawrence, J.A.; Davis, B.A. Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.S.; Taylor, S.; Thomas, C.; Weller, J.M. Social bias, discrimination and inequity in healthcare: Mechanisms, implications and recommendations. BJA Educ. 2022, 22, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondolo, E.; Gallo, L.C.; Myers, H.F. Race, racism and health: Disparities, mechanisms, and interventions. J. Behav. Med. 2009, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trawalter, S.; Bart-Plange, D.J.; Hoffman, K.M. A socioecological psychology of racism: Making structures and history more visible. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 32, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zestcott, C.A.; Blair, I.V.; Stone, J. Examining the presence, consequences, and reduction of implicit bias in health care: A narrative review. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2016, 19, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, L.A.; Dovidio, J.F.; Manning, M.A.; Albrecht, T.L.; van Ryn, M. Doing harm to some: Patient and provider attitudes and healthcare disparities. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Albarracín, D., Johnson, B.T., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, I.V.; Steiner, J.F.; Havranek, E.P. Unconscious (implicit) bias and health disparities: Where do we go from here? Perm. J. 2011, 15, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, S.; Bradby, H.; Ahlberg, B.M.; Thapar-Björkert, S. Racism in healthcare: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essex, R.; Markowski, M.; Miller, D. Structural injustice and dismantling racism in health and healthcare. Nurs. Inq. 2022, 29, e12441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, M.E.; Volpert-Esmond, H.I.; Deen, J.F.; Modde, E.; Warne, D. Stress and cardiometabolic disease risk for Indigenous populations throughout the lifespan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, M.B.; Erondu, A.I.; Smith, N.A.; Peek, M.E.; Woodruff, J.N.; Chin, M.H. Eliminating Explicit and Implicit Biases in Health Care: Evidence and Research Needs. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, D.P.; Chetty, U.; O’Donnell, P.; Gajria, C.; Blackadder-Weinstein, J. Implicit bias in healthcare: Clinical practice, research and decision making. Future Healthc. J. 2021, 8, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelin, J.R.; Siraj, D.S.; Victor, R.; Kotadia, S.; Maldonado, Y.A. The impact of unconscious bias in healthcare: How to recognize and mitigate it. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220 (Suppl. S2), S62–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzGerald, C.; Hurst, S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Med. Ethics 2017, 18, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, M.; Harrison, L. Providing culturally appropriate care: A literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, L.; Brown, J.B. Listening to native patients. Changes in physicians’ understanding and behaviour. Can. Fam. Physician 2002, 48, 1645–1652. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allen, L.; Hatala, A.; Ijaz, S.; Courchene, E.D.; Bushie, E.B. Indigenous-led health care partnerships in Canada. CMAJ 2020, 192, E208–E216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durie, M. Whaiora: Māori Health Development; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey, C.; Huria, T.; Beckert, L.; Gilles, M.; Pitama, S. The Hui Process: A framework to enhance the doctor–patient relationship with Māori. N. Zeal. Med. J. 2011, 124, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Thunderbird Partnership Foundation. First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework; Thunderbird Partnership Foundation: Bothwell, ON, Canada, 2021; Available online: https://thunderbirdpf.org/first-nations-mental-wellness-continuum-framework/ (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Rasmus, S.M.; Trickett, E.; Charles, B.; John, S.; Allen, J. The Qasgiq model as an Indigenous intervention: Using the cultural logic of contexts to build protective factors for Alaska Native suicide and alcohol misuse prevention. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2019, 25, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn-John Diné, M.; Koithan, M. Living in health, harmony, and beauty: The diné (navajo) hózhó wellness philosophy. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2015, 4, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, K.H. Social Determinants of Health, Volume 3; Office of Hawaiian Affairs: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.oha.org/wp-content/uploads/Volume-III-Social-Determinants-of-Health-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Lewis, M.E.; Modde, E.; Kamaka, M.; Maresca, T.; Horner, M.; Hudson, S.; Myhra, L. Development of the Indigenous Health Toolkit: A Toolkit Designed to Improve Indigenous Health Care Delivery in the United States. Int. J. Indig. Health 2024, 19, 41319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisolm-Straker, M.; Straker, H. Implicit bias in US medicine: Complex findings and incomplete conclusions. Int. J. Hum. Rights Healthc. 2017, 10, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovidio, J.F.; Eggly, S.; Albrecht, T.L.; Hagiwara, N.; Penner, L. Racial biases in medicine and healthcare disparities. TPM-Test. Psychom. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 23, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | SD | |

| Age (years) | 46 | 12 |

| Annual income | USD 11,709 | USD 9746 |

| n | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 16 | 80% |

| Male | 3 | 15% |

| Gender neutral | 1 | 5% |

| Tribal group | ||

| Anishinaabe | 20 | 75% |

| Lakota | 5 | 25% |

| Reported # of physical illnesses | ||

| 0 | 6 | 30% |

| 1 | 10 | 50% |

| 2 | 3 | 15% |

| 4 | 1 | 5% |

| Reported # of emotional illnesses | ||

| 0 | 6 | 30% |

| 1 | 9 | 45% |

| 2 | 3 | 15% |

| 3 | 2 | 10% |

| Reported substance use | ||

| 0 | 10 | 50% |

| 1 | 6 | 30% |

| 2 | 3 | 15% |

| 3 | 1 | 5% |

| First language (n = 19) | ||

| English | 16 | 84% |

| Indigenous (Anishinaabe or Lakota) | 3 | 16% |

| Language currently spoken (n = 19) | ||

| English only | 16 | 84% |

| English and Spanish | 2 | 10% |

| English and Indigenous (Anishinaabe or Lakota) | 1 | 1% |

| Assumptions | Examples from Focus Groups |

|---|---|

| Behavior | Drug seeking |

| Drug addict | |

| Alcoholic | |

| Capabilities | Not knowledgeable |

| Not smart | |

| Cannot make informed decisions | |

| Not capable parenting skills and knowledge | |

| Responsibility | Not fiscally responsible |

| Will not adhere to treatment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lewis, M.E.; Blackmore, I.; Kamaka, M.L.; Wildcat, S.; Anderson-Buettner, A.; Modde, E.; Myhra, L.; Smith, J.B.; Stately, A.L. “Understand the Way We Walk Our Life”: Indigenous Patients’ Experiences and Recommendations for Healthcare in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030445

Lewis ME, Blackmore I, Kamaka ML, Wildcat S, Anderson-Buettner A, Modde E, Myhra L, Smith JB, Stately AL. “Understand the Way We Walk Our Life”: Indigenous Patients’ Experiences and Recommendations for Healthcare in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(3):445. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030445

Chicago/Turabian StyleLewis, Melissa E., Ivy Blackmore, Martina L. Kamaka, Sky Wildcat, Amber Anderson-Buettner, Elizabeth Modde, Laurelle Myhra, Jamie B. Smith, and Antony L. Stately. 2025. "“Understand the Way We Walk Our Life”: Indigenous Patients’ Experiences and Recommendations for Healthcare in the United States" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 3: 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030445

APA StyleLewis, M. E., Blackmore, I., Kamaka, M. L., Wildcat, S., Anderson-Buettner, A., Modde, E., Myhra, L., Smith, J. B., & Stately, A. L. (2025). “Understand the Way We Walk Our Life”: Indigenous Patients’ Experiences and Recommendations for Healthcare in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(3), 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22030445